SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Authoritarian states have a genius for damaging themselves by the obsessive persecution of individual dissidents whom they thereby transform into celebrity martyrs. The Soviet Union used to do this with Andrei Sakharov, Alexander Solzhenitsyn and a host of lesser critics of its system. Today, it is the post 9/11 United States that discredits itself by its relentless pursuit of Edward Snowden under the pretense that he is an arch-traitor aiding the enemies of America.

Western Europeans often view the moral and political failings of the US with a certain secret satisfaction. Slavish imitation of American culture and political and economic norms traditionally combines with an undercurrent of resentment. But there is less to envy in America today. Whatever Osama bin Laden thought he was doing by staging 9/11 he tipped the US towards developing a menacing and ever-more powerful security apparatus. The US lost its immense advantage in world politics of being the country where people believed that they were not going to be unjustly jailed or otherwise mistreated by the state.

Snowden is very clear why he made his initial revelations about National Security Agency surveillance. He was enjoying "a very comfortable life" with a salary of $200,000, a home in Hawaii and a close and loving family. He said: "I'm willing to sacrifice all of that because I can't in good conscience allow the US government to destroy privacy, internet freedom and basic liberties for people around the world with this massive surveillance machine ...." He added: "My sole motive is to inform the public as to that which is done in their name and that which is done against them."

It is satisfying, if gruesome, to watch great powers shoot themselves in the foot. This was true of the mistreatment of Bradley Manning after the WikiLeaks revelations and it is true again of Snowden. Washington imagined it was a smart move to chase him into the limbo of the transit area in Moscow's main airport, but thereby guaranteed that he was at the centre of international attention, rather than allowing him to proceed to the great media-hub of Bogota (The Shah made a similar mistake in 1978 when he got Saddam Hussein to force Ayatollah Khomeini to quit Iraq for Paris).

One of the most striking features of the Snowden saga is the craven cooperation of most European states. That Spain, France, Italy and Portugal all denied passage to the plane of Bolivian President Evo Morales, in case Snowden might be on board, removes any doubts about US superpower status. There was little lasting anger in Europe, whatever the rage in Latin America, and there was a foretaste of the essential indifference of European intelligentsia, certainly in Britain, to freedom of expression and state secrecy last year, with the shallow media sneers at Julian Assange.

The only person in Europe to see Snowden's fate both in terms of political morality and in the context of the history of the US and Europe, is Rolf Hochhuth, the German author and playwright. He presented an eloquent petition to Chancellor Angela Merkel asking that Snowden be given asylum.

Hochhuth points out in the petition that where government is both accuser and perpetrator "the accused has no hope of justice". He added that if Snowden returns to the US he faces years in prison, but if he stays in Russia he will be permanently muzzled.

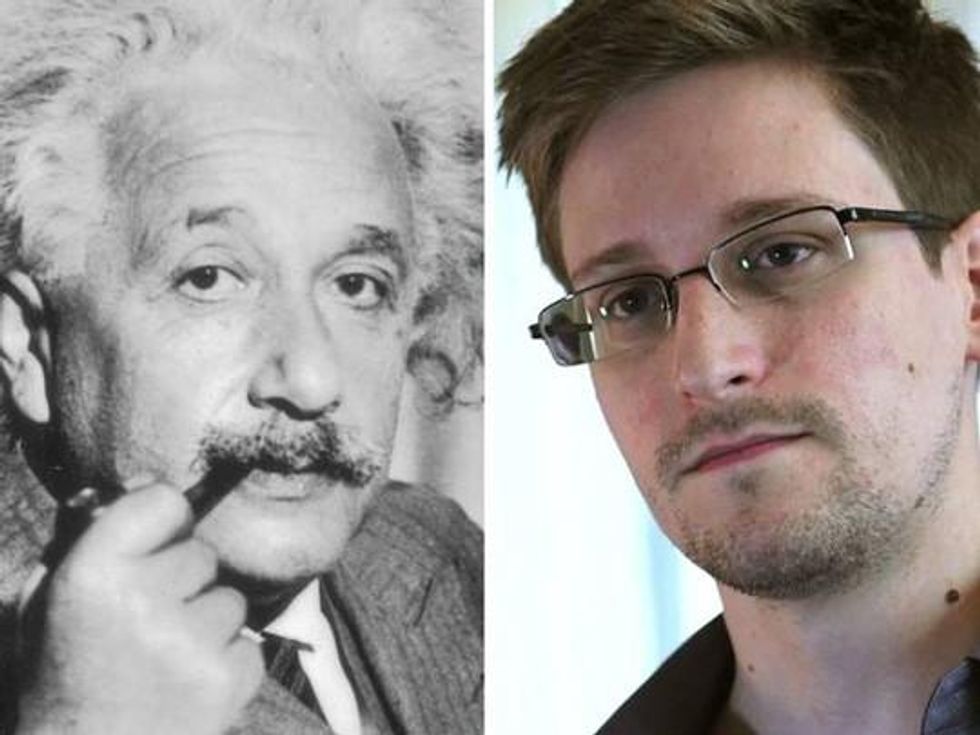

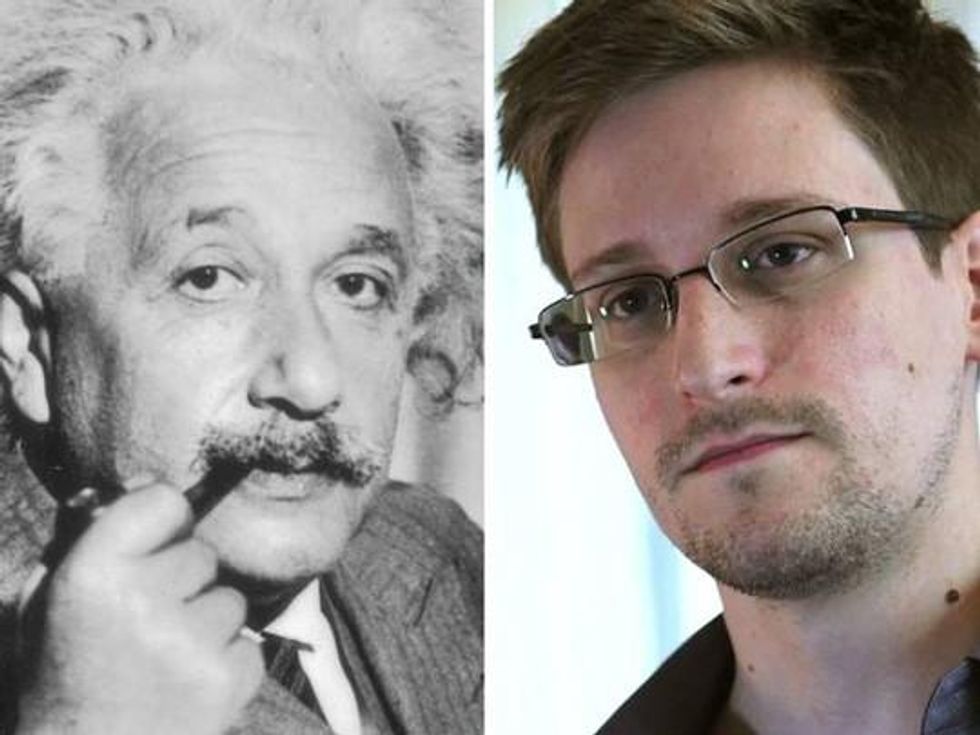

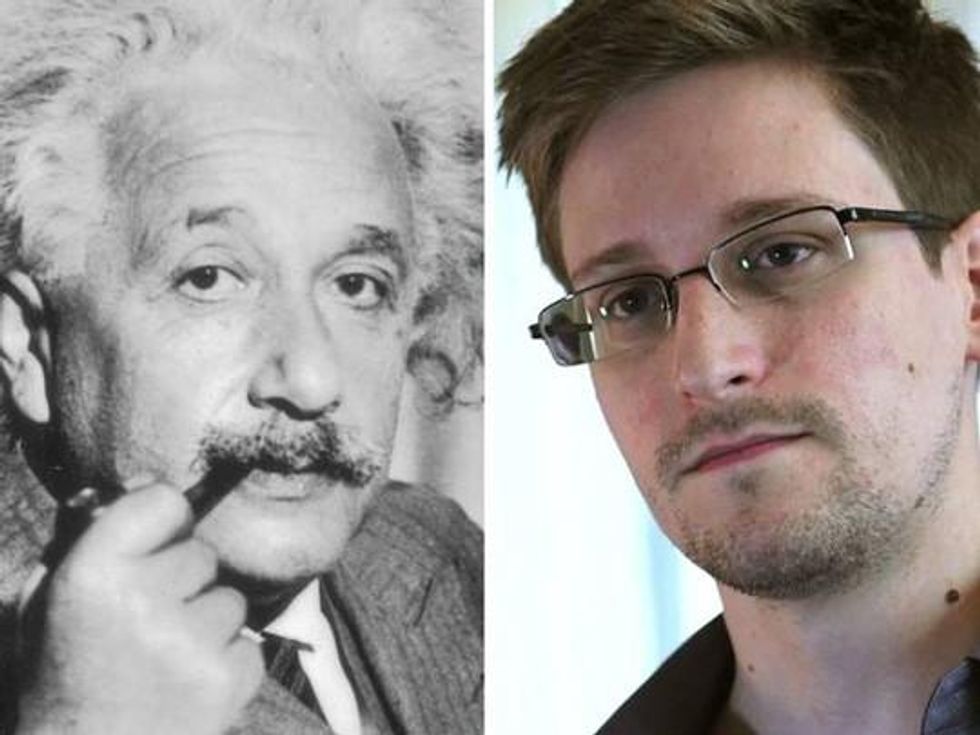

So, why should Germany of all countries offer asylum to an American? Hochhuth writes that "more than any other, the German people are obligated to honor the right of asylum because, beginning in 1933, our elite, without exception from the Mann brothers to Einstein, survived the 12-year Nazi dictatorship purely because other countries, with the US as the greatest example, offered asylum to these refugees."

Hochhuth emphasizes that he is far from being moved by any automatic anti-Americanism, but is motivated by memory of what the US did for Germany in the past. He remembers newsreel of when the Americans liberated Buchenwald in 1945 and saw Eisenhower in tears as he witnessed his GIs bulldozing mounds of corpses. "They could not understand how we Germans could have been capable of such acts. Yet what was America's answer? Through their airlift they rescued Berlin from Stalin's grasp."

Hochhuth argues that the US has changed, saying "no nation remains lastingly great". It might be difficult to sustain a charge of treason against Snowden in the US, but he could still receive multiple 10-year sentences, under the Espionage Act, for revealing classified information. Hochhuth cites with approval George Bernard Shaw's somewhat self-regarding bon mot: "I am held to be a master of irony. But even I would not have had the idea of erecting the Statue of Liberty in New York."

In its pursuit of Snowden the US government has given substance to his accusations about an over-mighty and uncontrolled security apparatus. The sovereign rights of independent states have been trodden down as readily as the rights of individuals. Hochhuth asks Merkel whether "you know of a similar act over a European state which considers itself sovereign, an act by which for 12 hours orders from the US prevent the plane of a South American president continuing its flight?"

Aside from Hochhuth, there is something neutered and pro forma about the response of Europe's leaders to Snowden's revelations despite initial expressions of shock and anger. The British may have been subjected to less intense surveillance, but even if that were not so it is doubtful that they would care. Almost every significant act in Britain's foreign policy over the past 30 years has been geared to strengthening its status as America's greatest ally.

Concern for human rights and liberty is at its height when the abuses happen in Benghazi, Aleppo or Homs, but it ebbs to nothing when the abuse is closer to home or involves US citizens.

"It is the highest moral duty of Germany to give asylum to Edward Snowden," concludes Hochhuth's petition, "[because] we as no other Europeans are duty bound in the light of our shameful past!"

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Authoritarian states have a genius for damaging themselves by the obsessive persecution of individual dissidents whom they thereby transform into celebrity martyrs. The Soviet Union used to do this with Andrei Sakharov, Alexander Solzhenitsyn and a host of lesser critics of its system. Today, it is the post 9/11 United States that discredits itself by its relentless pursuit of Edward Snowden under the pretense that he is an arch-traitor aiding the enemies of America.

Western Europeans often view the moral and political failings of the US with a certain secret satisfaction. Slavish imitation of American culture and political and economic norms traditionally combines with an undercurrent of resentment. But there is less to envy in America today. Whatever Osama bin Laden thought he was doing by staging 9/11 he tipped the US towards developing a menacing and ever-more powerful security apparatus. The US lost its immense advantage in world politics of being the country where people believed that they were not going to be unjustly jailed or otherwise mistreated by the state.

Snowden is very clear why he made his initial revelations about National Security Agency surveillance. He was enjoying "a very comfortable life" with a salary of $200,000, a home in Hawaii and a close and loving family. He said: "I'm willing to sacrifice all of that because I can't in good conscience allow the US government to destroy privacy, internet freedom and basic liberties for people around the world with this massive surveillance machine ...." He added: "My sole motive is to inform the public as to that which is done in their name and that which is done against them."

It is satisfying, if gruesome, to watch great powers shoot themselves in the foot. This was true of the mistreatment of Bradley Manning after the WikiLeaks revelations and it is true again of Snowden. Washington imagined it was a smart move to chase him into the limbo of the transit area in Moscow's main airport, but thereby guaranteed that he was at the centre of international attention, rather than allowing him to proceed to the great media-hub of Bogota (The Shah made a similar mistake in 1978 when he got Saddam Hussein to force Ayatollah Khomeini to quit Iraq for Paris).

One of the most striking features of the Snowden saga is the craven cooperation of most European states. That Spain, France, Italy and Portugal all denied passage to the plane of Bolivian President Evo Morales, in case Snowden might be on board, removes any doubts about US superpower status. There was little lasting anger in Europe, whatever the rage in Latin America, and there was a foretaste of the essential indifference of European intelligentsia, certainly in Britain, to freedom of expression and state secrecy last year, with the shallow media sneers at Julian Assange.

The only person in Europe to see Snowden's fate both in terms of political morality and in the context of the history of the US and Europe, is Rolf Hochhuth, the German author and playwright. He presented an eloquent petition to Chancellor Angela Merkel asking that Snowden be given asylum.

Hochhuth points out in the petition that where government is both accuser and perpetrator "the accused has no hope of justice". He added that if Snowden returns to the US he faces years in prison, but if he stays in Russia he will be permanently muzzled.

So, why should Germany of all countries offer asylum to an American? Hochhuth writes that "more than any other, the German people are obligated to honor the right of asylum because, beginning in 1933, our elite, without exception from the Mann brothers to Einstein, survived the 12-year Nazi dictatorship purely because other countries, with the US as the greatest example, offered asylum to these refugees."

Hochhuth emphasizes that he is far from being moved by any automatic anti-Americanism, but is motivated by memory of what the US did for Germany in the past. He remembers newsreel of when the Americans liberated Buchenwald in 1945 and saw Eisenhower in tears as he witnessed his GIs bulldozing mounds of corpses. "They could not understand how we Germans could have been capable of such acts. Yet what was America's answer? Through their airlift they rescued Berlin from Stalin's grasp."

Hochhuth argues that the US has changed, saying "no nation remains lastingly great". It might be difficult to sustain a charge of treason against Snowden in the US, but he could still receive multiple 10-year sentences, under the Espionage Act, for revealing classified information. Hochhuth cites with approval George Bernard Shaw's somewhat self-regarding bon mot: "I am held to be a master of irony. But even I would not have had the idea of erecting the Statue of Liberty in New York."

In its pursuit of Snowden the US government has given substance to his accusations about an over-mighty and uncontrolled security apparatus. The sovereign rights of independent states have been trodden down as readily as the rights of individuals. Hochhuth asks Merkel whether "you know of a similar act over a European state which considers itself sovereign, an act by which for 12 hours orders from the US prevent the plane of a South American president continuing its flight?"

Aside from Hochhuth, there is something neutered and pro forma about the response of Europe's leaders to Snowden's revelations despite initial expressions of shock and anger. The British may have been subjected to less intense surveillance, but even if that were not so it is doubtful that they would care. Almost every significant act in Britain's foreign policy over the past 30 years has been geared to strengthening its status as America's greatest ally.

Concern for human rights and liberty is at its height when the abuses happen in Benghazi, Aleppo or Homs, but it ebbs to nothing when the abuse is closer to home or involves US citizens.

"It is the highest moral duty of Germany to give asylum to Edward Snowden," concludes Hochhuth's petition, "[because] we as no other Europeans are duty bound in the light of our shameful past!"

Authoritarian states have a genius for damaging themselves by the obsessive persecution of individual dissidents whom they thereby transform into celebrity martyrs. The Soviet Union used to do this with Andrei Sakharov, Alexander Solzhenitsyn and a host of lesser critics of its system. Today, it is the post 9/11 United States that discredits itself by its relentless pursuit of Edward Snowden under the pretense that he is an arch-traitor aiding the enemies of America.

Western Europeans often view the moral and political failings of the US with a certain secret satisfaction. Slavish imitation of American culture and political and economic norms traditionally combines with an undercurrent of resentment. But there is less to envy in America today. Whatever Osama bin Laden thought he was doing by staging 9/11 he tipped the US towards developing a menacing and ever-more powerful security apparatus. The US lost its immense advantage in world politics of being the country where people believed that they were not going to be unjustly jailed or otherwise mistreated by the state.

Snowden is very clear why he made his initial revelations about National Security Agency surveillance. He was enjoying "a very comfortable life" with a salary of $200,000, a home in Hawaii and a close and loving family. He said: "I'm willing to sacrifice all of that because I can't in good conscience allow the US government to destroy privacy, internet freedom and basic liberties for people around the world with this massive surveillance machine ...." He added: "My sole motive is to inform the public as to that which is done in their name and that which is done against them."

It is satisfying, if gruesome, to watch great powers shoot themselves in the foot. This was true of the mistreatment of Bradley Manning after the WikiLeaks revelations and it is true again of Snowden. Washington imagined it was a smart move to chase him into the limbo of the transit area in Moscow's main airport, but thereby guaranteed that he was at the centre of international attention, rather than allowing him to proceed to the great media-hub of Bogota (The Shah made a similar mistake in 1978 when he got Saddam Hussein to force Ayatollah Khomeini to quit Iraq for Paris).

One of the most striking features of the Snowden saga is the craven cooperation of most European states. That Spain, France, Italy and Portugal all denied passage to the plane of Bolivian President Evo Morales, in case Snowden might be on board, removes any doubts about US superpower status. There was little lasting anger in Europe, whatever the rage in Latin America, and there was a foretaste of the essential indifference of European intelligentsia, certainly in Britain, to freedom of expression and state secrecy last year, with the shallow media sneers at Julian Assange.

The only person in Europe to see Snowden's fate both in terms of political morality and in the context of the history of the US and Europe, is Rolf Hochhuth, the German author and playwright. He presented an eloquent petition to Chancellor Angela Merkel asking that Snowden be given asylum.

Hochhuth points out in the petition that where government is both accuser and perpetrator "the accused has no hope of justice". He added that if Snowden returns to the US he faces years in prison, but if he stays in Russia he will be permanently muzzled.

So, why should Germany of all countries offer asylum to an American? Hochhuth writes that "more than any other, the German people are obligated to honor the right of asylum because, beginning in 1933, our elite, without exception from the Mann brothers to Einstein, survived the 12-year Nazi dictatorship purely because other countries, with the US as the greatest example, offered asylum to these refugees."

Hochhuth emphasizes that he is far from being moved by any automatic anti-Americanism, but is motivated by memory of what the US did for Germany in the past. He remembers newsreel of when the Americans liberated Buchenwald in 1945 and saw Eisenhower in tears as he witnessed his GIs bulldozing mounds of corpses. "They could not understand how we Germans could have been capable of such acts. Yet what was America's answer? Through their airlift they rescued Berlin from Stalin's grasp."

Hochhuth argues that the US has changed, saying "no nation remains lastingly great". It might be difficult to sustain a charge of treason against Snowden in the US, but he could still receive multiple 10-year sentences, under the Espionage Act, for revealing classified information. Hochhuth cites with approval George Bernard Shaw's somewhat self-regarding bon mot: "I am held to be a master of irony. But even I would not have had the idea of erecting the Statue of Liberty in New York."

In its pursuit of Snowden the US government has given substance to his accusations about an over-mighty and uncontrolled security apparatus. The sovereign rights of independent states have been trodden down as readily as the rights of individuals. Hochhuth asks Merkel whether "you know of a similar act over a European state which considers itself sovereign, an act by which for 12 hours orders from the US prevent the plane of a South American president continuing its flight?"

Aside from Hochhuth, there is something neutered and pro forma about the response of Europe's leaders to Snowden's revelations despite initial expressions of shock and anger. The British may have been subjected to less intense surveillance, but even if that were not so it is doubtful that they would care. Almost every significant act in Britain's foreign policy over the past 30 years has been geared to strengthening its status as America's greatest ally.

Concern for human rights and liberty is at its height when the abuses happen in Benghazi, Aleppo or Homs, but it ebbs to nothing when the abuse is closer to home or involves US citizens.

"It is the highest moral duty of Germany to give asylum to Edward Snowden," concludes Hochhuth's petition, "[because] we as no other Europeans are duty bound in the light of our shameful past!"