Extreme Wealth vs Global Sharing

Last year alone, the world's 100 richest people earned a combined additional income of $241 billion. According to new calculations, redistributing just a quarter of this vast quantity of money would enable governments to wipe out extreme poverty for an entire year. Unfortunately for the 40,000 people who die needlessly every day from poverty-related causes, these billionaires are as unlikely to share their earnings voluntarily as governments are to enact policies that redistribute their excessive incomes more fairly across society.

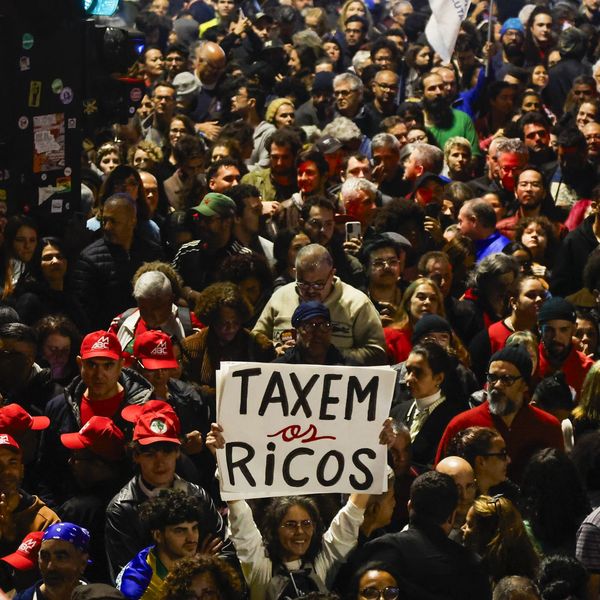

In the latest in a string of reports, books and public protests by those calling for sharing and justice to guide social and economic policy, Oxfam has put forward a robust argument for putting an end to extreme wealth by 2025. In their media briefing, 'The cost of inequality: how wealth and income extremes hurt us all', the charity gives a litany of reasons why extreme inequality is bad for the economy, the environment and society in general.

According to the briefing, the incomes of the top 1% of the world's population have increased 60% in the past twenty years. While joblessness rocketed across the US and Europe after the financial crisis of 2008, the income of this elite group of multimillionaires continued to expand. And the growth in income for the top 0.01% has been even greater - there are now around 1200 billionaires in the world. Unsurprisingly, the market for luxury goods has 'registered double-digit growth every year since the [financial] crisis hit'.

Despite notable reductions in the number of people living in extreme poverty, the paper also highlights the rapid escalation of inequality in developing countries. For example, in China the top 10% of the population now earn nearly 60% of the country's income, which places it almost on par with South Africa as one of the most unequal countries on earth. This trend has been just as pronounced in rich countries such as the UK, where inequality levels are fast reaching Dickensian proportions. Similarly, in the US the share of national income since 1980 has doubled for the top 1% and quadrupled for the top 0.01%.

The slow death of neoliberalism

It is important to understand the root cause of this all-pervasive growth in inequality and determine whether it constitutes a serious problem for society. As George Monbiot reminded us in a recent article, for many decades policymakers have regarded inequality as a necessary by-product of the neoliberal ideology to which they subscribe. For adherents of this extreme pro-market belief system, any attempts to enact policies to reduce inequality interfere with the efficiency of the free market and should be avoided at all costs. Instead more should be done to further deregulate economies, privatise resources, services and industry, downsize the public sector and open up markets to even more competition both within and between nations. As a theory based on the principles of individualism and self-interest, neoliberalism seeks to remove collective public oversight from economic activity, even when this could have dire implications for society and the environment.

But the neoliberal experiment, which was most vociferously pursued by Thatcher, Regan, Kohl and others from the 1980s onwards, is now widely regarded as having been an utter failure - most notably in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. As Monbiot explains, the growth in rich nations that occurred prior to the 1980s "was made possible by the destruction of the wealth and power of the elite, as a result of the Depression and the second world war." The neoliberal experiment reversed these trends and, despite the weight of evidence against these policies, five years after the financial crisis the thrust of economic policy remains almost wholly neoliberal in nature.

There is of course the age-old moral argument against allowing excessive levels of wealth and riches to exist alongside extreme poverty and deprivation. This is a basic ethical notion that rings true to the majority of people in rich and poor countries alike, and it has been a cornerstone of spiritual and religious philosophy for millennia. But even within the sadly amoral framework of economic decision-making today, it is widely accepted that neoliberal polices have failed to share the proceeds of growth fairly and led to levels of inequality that now threaten to undermine the very fabric of society.

The consequences of inequality

Oxfam is only one of a number of organisations that have reported on the human, economic and environmental impact of inequality in recent years, and the issue has been central to the discourse on a post-2015 development goal that can address inequality head on. In a misguided world where the pursuit of short-term economic growth remains the holy grail of public policy, even the International Monetary Fund is beginning to accede that inequality can stymie efficiency. In a recent report entitled 'Fair Share', the Fund suggests that governments in both rich and developing countries should place more emphasis on progressive taxation and redistribution - policies that essentially embody the principle of sharing.

Also highlighted in the Oxfam briefing is the way extreme wealth can damage democracy, especially through the enormous influence over the political process that money and power can buy. Many billions of dollars are spent each year by the financial industry and large corporations in lobbying politicians to pursue a market friendly agenda - the same neoliberal policies that have widened inequalities and eventually led to a global financial collapse in 2008. Resuscitating representative democracy will inevitably entail curbing the ability of any minority group to exert a disproportionate influence over political outcomes, which in turn might require limiting the excessive wealth that can facilitate this distortion.

Policies that exaggerate inequality have also been a key driver of environmental degradation, as people in rich nations consume far more than their fair share of the earth's finite resources. As Oxfam also previously highlighted in a discussion paper on planetary boundaries, it will be impossible to address ecological and social crises unless we share available resources more equitably and sustainably. The aim of development and environmental policy must be to ensure that people in all nations can secure their basic needs without transgressing environmental limits. Such statements have huge implications for policies that widen inequalities as they point to an urgent need for convergence and equity.

As the historic events of 2011 demonstrated, inequality can also spur violent civil unrest. The experience of inequality and injustice over many years ultimately sparked the Arab Spring protests as well as many other spontaneous public demonstrations - from the global Occupy Movement to the protests in Spain, Greece, Israel and other countries in the same year. Many of those involved in these public mobilisations had first-hand experience of the social consequences of inequality that campaigners and analysts have long warned of. As explicitly detailed in the classic book The Spirit Level, it is now widely accepted that inequality impacts adversely on almost all indicators of societal wellbeing, from crime and obesity to mental health.

Sharing as the obvious antidote

Whether in discussions about the post-2015 development goals or in proposals for how to create an environmentally sustainable economy, it is increasingly difficult for policymakers to ignore the need to reverse decades of neoliberal policies and instead strengthen forms of sharing and redistribution. Policies guided by the principle of sharing are inimical to the neoliberal agenda as the very process of sharing is cooperative rather than individualistic. Systems of sharing such as progressive taxation and the provision of social welfare and public services have the power to build solidarity, bring communities and nations together, and help close the inequality gap.

Oxfam's report on the costs of inequality adds further weight to a growing body of research pointing to how forms of sharing and redistribution could have an important role in reducing inequality. Redistributing the combined annual income of the richest 100 billionaires may not be a workable temporary solution to world poverty unless the wealthy voluntarily share their bounty. But as Oxfam acknowledge, policy solutions for reducing inequality are plentiful and widely known. As one practical example, our recent report on 'Financing the global sharing economy' demonstrates that governments could redistribute trillions of dollars to reduce extreme inequality through a variety of measures that range from tax and debt justice to redirecting perverse government subsidies.

Regardless of the specific policies employed, sharing wealth and resources more equitably will require governments to overcome their fixation on an unsustainable model of development based on outdated assumptions about human nature. And however much neoliberals find it anathema, this will inevitably require government intervention: new policies, regulations and laws that guarantee fairness and equity in society, both nationally and globally.

Will ordinary people lead the way?

While governments remain preoccupied in trying to resurrect the old economic order, many questions will no doubt occupy the minds of campaigners and progressives across the world. In light of the mounting need for sharing and redistribution, what will the public have to do to wrestle politicians away from their fixation on policies that promote inequality? For how much longer will policymakers continue to ignore the common sense alternatives that millions of people across the world are calling for? What can be done to strengthen democracy and remind politicians that they are in office to serve ordinary people, not corporations?

Perhaps the only answer is the mass mobilisation of engaged citizens in a common cause against rising inequality that extends beyond national borders. Or perhaps only further financial crises, environmental chaos and economic hardship will eventually force policymakers to rethink their distorted priorities. Irrespective of how transformative change finally takes place, it is clear that a much greater emphasis on sharing and redistribution will need to be at the heart of any program to reduce inequality and secure human needs within planetary limits. Otherwise, it might not be long before the annual income of the world's richest person alone is sufficient to end global poverty.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Last year alone, the world's 100 richest people earned a combined additional income of $241 billion. According to new calculations, redistributing just a quarter of this vast quantity of money would enable governments to wipe out extreme poverty for an entire year. Unfortunately for the 40,000 people who die needlessly every day from poverty-related causes, these billionaires are as unlikely to share their earnings voluntarily as governments are to enact policies that redistribute their excessive incomes more fairly across society.

In the latest in a string of reports, books and public protests by those calling for sharing and justice to guide social and economic policy, Oxfam has put forward a robust argument for putting an end to extreme wealth by 2025. In their media briefing, 'The cost of inequality: how wealth and income extremes hurt us all', the charity gives a litany of reasons why extreme inequality is bad for the economy, the environment and society in general.

According to the briefing, the incomes of the top 1% of the world's population have increased 60% in the past twenty years. While joblessness rocketed across the US and Europe after the financial crisis of 2008, the income of this elite group of multimillionaires continued to expand. And the growth in income for the top 0.01% has been even greater - there are now around 1200 billionaires in the world. Unsurprisingly, the market for luxury goods has 'registered double-digit growth every year since the [financial] crisis hit'.

Despite notable reductions in the number of people living in extreme poverty, the paper also highlights the rapid escalation of inequality in developing countries. For example, in China the top 10% of the population now earn nearly 60% of the country's income, which places it almost on par with South Africa as one of the most unequal countries on earth. This trend has been just as pronounced in rich countries such as the UK, where inequality levels are fast reaching Dickensian proportions. Similarly, in the US the share of national income since 1980 has doubled for the top 1% and quadrupled for the top 0.01%.

The slow death of neoliberalism

It is important to understand the root cause of this all-pervasive growth in inequality and determine whether it constitutes a serious problem for society. As George Monbiot reminded us in a recent article, for many decades policymakers have regarded inequality as a necessary by-product of the neoliberal ideology to which they subscribe. For adherents of this extreme pro-market belief system, any attempts to enact policies to reduce inequality interfere with the efficiency of the free market and should be avoided at all costs. Instead more should be done to further deregulate economies, privatise resources, services and industry, downsize the public sector and open up markets to even more competition both within and between nations. As a theory based on the principles of individualism and self-interest, neoliberalism seeks to remove collective public oversight from economic activity, even when this could have dire implications for society and the environment.

But the neoliberal experiment, which was most vociferously pursued by Thatcher, Regan, Kohl and others from the 1980s onwards, is now widely regarded as having been an utter failure - most notably in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. As Monbiot explains, the growth in rich nations that occurred prior to the 1980s "was made possible by the destruction of the wealth and power of the elite, as a result of the Depression and the second world war." The neoliberal experiment reversed these trends and, despite the weight of evidence against these policies, five years after the financial crisis the thrust of economic policy remains almost wholly neoliberal in nature.

There is of course the age-old moral argument against allowing excessive levels of wealth and riches to exist alongside extreme poverty and deprivation. This is a basic ethical notion that rings true to the majority of people in rich and poor countries alike, and it has been a cornerstone of spiritual and religious philosophy for millennia. But even within the sadly amoral framework of economic decision-making today, it is widely accepted that neoliberal polices have failed to share the proceeds of growth fairly and led to levels of inequality that now threaten to undermine the very fabric of society.

The consequences of inequality

Oxfam is only one of a number of organisations that have reported on the human, economic and environmental impact of inequality in recent years, and the issue has been central to the discourse on a post-2015 development goal that can address inequality head on. In a misguided world where the pursuit of short-term economic growth remains the holy grail of public policy, even the International Monetary Fund is beginning to accede that inequality can stymie efficiency. In a recent report entitled 'Fair Share', the Fund suggests that governments in both rich and developing countries should place more emphasis on progressive taxation and redistribution - policies that essentially embody the principle of sharing.

Also highlighted in the Oxfam briefing is the way extreme wealth can damage democracy, especially through the enormous influence over the political process that money and power can buy. Many billions of dollars are spent each year by the financial industry and large corporations in lobbying politicians to pursue a market friendly agenda - the same neoliberal policies that have widened inequalities and eventually led to a global financial collapse in 2008. Resuscitating representative democracy will inevitably entail curbing the ability of any minority group to exert a disproportionate influence over political outcomes, which in turn might require limiting the excessive wealth that can facilitate this distortion.

Policies that exaggerate inequality have also been a key driver of environmental degradation, as people in rich nations consume far more than their fair share of the earth's finite resources. As Oxfam also previously highlighted in a discussion paper on planetary boundaries, it will be impossible to address ecological and social crises unless we share available resources more equitably and sustainably. The aim of development and environmental policy must be to ensure that people in all nations can secure their basic needs without transgressing environmental limits. Such statements have huge implications for policies that widen inequalities as they point to an urgent need for convergence and equity.

As the historic events of 2011 demonstrated, inequality can also spur violent civil unrest. The experience of inequality and injustice over many years ultimately sparked the Arab Spring protests as well as many other spontaneous public demonstrations - from the global Occupy Movement to the protests in Spain, Greece, Israel and other countries in the same year. Many of those involved in these public mobilisations had first-hand experience of the social consequences of inequality that campaigners and analysts have long warned of. As explicitly detailed in the classic book The Spirit Level, it is now widely accepted that inequality impacts adversely on almost all indicators of societal wellbeing, from crime and obesity to mental health.

Sharing as the obvious antidote

Whether in discussions about the post-2015 development goals or in proposals for how to create an environmentally sustainable economy, it is increasingly difficult for policymakers to ignore the need to reverse decades of neoliberal policies and instead strengthen forms of sharing and redistribution. Policies guided by the principle of sharing are inimical to the neoliberal agenda as the very process of sharing is cooperative rather than individualistic. Systems of sharing such as progressive taxation and the provision of social welfare and public services have the power to build solidarity, bring communities and nations together, and help close the inequality gap.

Oxfam's report on the costs of inequality adds further weight to a growing body of research pointing to how forms of sharing and redistribution could have an important role in reducing inequality. Redistributing the combined annual income of the richest 100 billionaires may not be a workable temporary solution to world poverty unless the wealthy voluntarily share their bounty. But as Oxfam acknowledge, policy solutions for reducing inequality are plentiful and widely known. As one practical example, our recent report on 'Financing the global sharing economy' demonstrates that governments could redistribute trillions of dollars to reduce extreme inequality through a variety of measures that range from tax and debt justice to redirecting perverse government subsidies.

Regardless of the specific policies employed, sharing wealth and resources more equitably will require governments to overcome their fixation on an unsustainable model of development based on outdated assumptions about human nature. And however much neoliberals find it anathema, this will inevitably require government intervention: new policies, regulations and laws that guarantee fairness and equity in society, both nationally and globally.

Will ordinary people lead the way?

While governments remain preoccupied in trying to resurrect the old economic order, many questions will no doubt occupy the minds of campaigners and progressives across the world. In light of the mounting need for sharing and redistribution, what will the public have to do to wrestle politicians away from their fixation on policies that promote inequality? For how much longer will policymakers continue to ignore the common sense alternatives that millions of people across the world are calling for? What can be done to strengthen democracy and remind politicians that they are in office to serve ordinary people, not corporations?

Perhaps the only answer is the mass mobilisation of engaged citizens in a common cause against rising inequality that extends beyond national borders. Or perhaps only further financial crises, environmental chaos and economic hardship will eventually force policymakers to rethink their distorted priorities. Irrespective of how transformative change finally takes place, it is clear that a much greater emphasis on sharing and redistribution will need to be at the heart of any program to reduce inequality and secure human needs within planetary limits. Otherwise, it might not be long before the annual income of the world's richest person alone is sufficient to end global poverty.

Last year alone, the world's 100 richest people earned a combined additional income of $241 billion. According to new calculations, redistributing just a quarter of this vast quantity of money would enable governments to wipe out extreme poverty for an entire year. Unfortunately for the 40,000 people who die needlessly every day from poverty-related causes, these billionaires are as unlikely to share their earnings voluntarily as governments are to enact policies that redistribute their excessive incomes more fairly across society.

In the latest in a string of reports, books and public protests by those calling for sharing and justice to guide social and economic policy, Oxfam has put forward a robust argument for putting an end to extreme wealth by 2025. In their media briefing, 'The cost of inequality: how wealth and income extremes hurt us all', the charity gives a litany of reasons why extreme inequality is bad for the economy, the environment and society in general.

According to the briefing, the incomes of the top 1% of the world's population have increased 60% in the past twenty years. While joblessness rocketed across the US and Europe after the financial crisis of 2008, the income of this elite group of multimillionaires continued to expand. And the growth in income for the top 0.01% has been even greater - there are now around 1200 billionaires in the world. Unsurprisingly, the market for luxury goods has 'registered double-digit growth every year since the [financial] crisis hit'.

Despite notable reductions in the number of people living in extreme poverty, the paper also highlights the rapid escalation of inequality in developing countries. For example, in China the top 10% of the population now earn nearly 60% of the country's income, which places it almost on par with South Africa as one of the most unequal countries on earth. This trend has been just as pronounced in rich countries such as the UK, where inequality levels are fast reaching Dickensian proportions. Similarly, in the US the share of national income since 1980 has doubled for the top 1% and quadrupled for the top 0.01%.

The slow death of neoliberalism

It is important to understand the root cause of this all-pervasive growth in inequality and determine whether it constitutes a serious problem for society. As George Monbiot reminded us in a recent article, for many decades policymakers have regarded inequality as a necessary by-product of the neoliberal ideology to which they subscribe. For adherents of this extreme pro-market belief system, any attempts to enact policies to reduce inequality interfere with the efficiency of the free market and should be avoided at all costs. Instead more should be done to further deregulate economies, privatise resources, services and industry, downsize the public sector and open up markets to even more competition both within and between nations. As a theory based on the principles of individualism and self-interest, neoliberalism seeks to remove collective public oversight from economic activity, even when this could have dire implications for society and the environment.

But the neoliberal experiment, which was most vociferously pursued by Thatcher, Regan, Kohl and others from the 1980s onwards, is now widely regarded as having been an utter failure - most notably in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. As Monbiot explains, the growth in rich nations that occurred prior to the 1980s "was made possible by the destruction of the wealth and power of the elite, as a result of the Depression and the second world war." The neoliberal experiment reversed these trends and, despite the weight of evidence against these policies, five years after the financial crisis the thrust of economic policy remains almost wholly neoliberal in nature.

There is of course the age-old moral argument against allowing excessive levels of wealth and riches to exist alongside extreme poverty and deprivation. This is a basic ethical notion that rings true to the majority of people in rich and poor countries alike, and it has been a cornerstone of spiritual and religious philosophy for millennia. But even within the sadly amoral framework of economic decision-making today, it is widely accepted that neoliberal polices have failed to share the proceeds of growth fairly and led to levels of inequality that now threaten to undermine the very fabric of society.

The consequences of inequality

Oxfam is only one of a number of organisations that have reported on the human, economic and environmental impact of inequality in recent years, and the issue has been central to the discourse on a post-2015 development goal that can address inequality head on. In a misguided world where the pursuit of short-term economic growth remains the holy grail of public policy, even the International Monetary Fund is beginning to accede that inequality can stymie efficiency. In a recent report entitled 'Fair Share', the Fund suggests that governments in both rich and developing countries should place more emphasis on progressive taxation and redistribution - policies that essentially embody the principle of sharing.

Also highlighted in the Oxfam briefing is the way extreme wealth can damage democracy, especially through the enormous influence over the political process that money and power can buy. Many billions of dollars are spent each year by the financial industry and large corporations in lobbying politicians to pursue a market friendly agenda - the same neoliberal policies that have widened inequalities and eventually led to a global financial collapse in 2008. Resuscitating representative democracy will inevitably entail curbing the ability of any minority group to exert a disproportionate influence over political outcomes, which in turn might require limiting the excessive wealth that can facilitate this distortion.

Policies that exaggerate inequality have also been a key driver of environmental degradation, as people in rich nations consume far more than their fair share of the earth's finite resources. As Oxfam also previously highlighted in a discussion paper on planetary boundaries, it will be impossible to address ecological and social crises unless we share available resources more equitably and sustainably. The aim of development and environmental policy must be to ensure that people in all nations can secure their basic needs without transgressing environmental limits. Such statements have huge implications for policies that widen inequalities as they point to an urgent need for convergence and equity.

As the historic events of 2011 demonstrated, inequality can also spur violent civil unrest. The experience of inequality and injustice over many years ultimately sparked the Arab Spring protests as well as many other spontaneous public demonstrations - from the global Occupy Movement to the protests in Spain, Greece, Israel and other countries in the same year. Many of those involved in these public mobilisations had first-hand experience of the social consequences of inequality that campaigners and analysts have long warned of. As explicitly detailed in the classic book The Spirit Level, it is now widely accepted that inequality impacts adversely on almost all indicators of societal wellbeing, from crime and obesity to mental health.

Sharing as the obvious antidote

Whether in discussions about the post-2015 development goals or in proposals for how to create an environmentally sustainable economy, it is increasingly difficult for policymakers to ignore the need to reverse decades of neoliberal policies and instead strengthen forms of sharing and redistribution. Policies guided by the principle of sharing are inimical to the neoliberal agenda as the very process of sharing is cooperative rather than individualistic. Systems of sharing such as progressive taxation and the provision of social welfare and public services have the power to build solidarity, bring communities and nations together, and help close the inequality gap.

Oxfam's report on the costs of inequality adds further weight to a growing body of research pointing to how forms of sharing and redistribution could have an important role in reducing inequality. Redistributing the combined annual income of the richest 100 billionaires may not be a workable temporary solution to world poverty unless the wealthy voluntarily share their bounty. But as Oxfam acknowledge, policy solutions for reducing inequality are plentiful and widely known. As one practical example, our recent report on 'Financing the global sharing economy' demonstrates that governments could redistribute trillions of dollars to reduce extreme inequality through a variety of measures that range from tax and debt justice to redirecting perverse government subsidies.

Regardless of the specific policies employed, sharing wealth and resources more equitably will require governments to overcome their fixation on an unsustainable model of development based on outdated assumptions about human nature. And however much neoliberals find it anathema, this will inevitably require government intervention: new policies, regulations and laws that guarantee fairness and equity in society, both nationally and globally.

Will ordinary people lead the way?

While governments remain preoccupied in trying to resurrect the old economic order, many questions will no doubt occupy the minds of campaigners and progressives across the world. In light of the mounting need for sharing and redistribution, what will the public have to do to wrestle politicians away from their fixation on policies that promote inequality? For how much longer will policymakers continue to ignore the common sense alternatives that millions of people across the world are calling for? What can be done to strengthen democracy and remind politicians that they are in office to serve ordinary people, not corporations?

Perhaps the only answer is the mass mobilisation of engaged citizens in a common cause against rising inequality that extends beyond national borders. Or perhaps only further financial crises, environmental chaos and economic hardship will eventually force policymakers to rethink their distorted priorities. Irrespective of how transformative change finally takes place, it is clear that a much greater emphasis on sharing and redistribution will need to be at the heart of any program to reduce inequality and secure human needs within planetary limits. Otherwise, it might not be long before the annual income of the world's richest person alone is sufficient to end global poverty.