SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

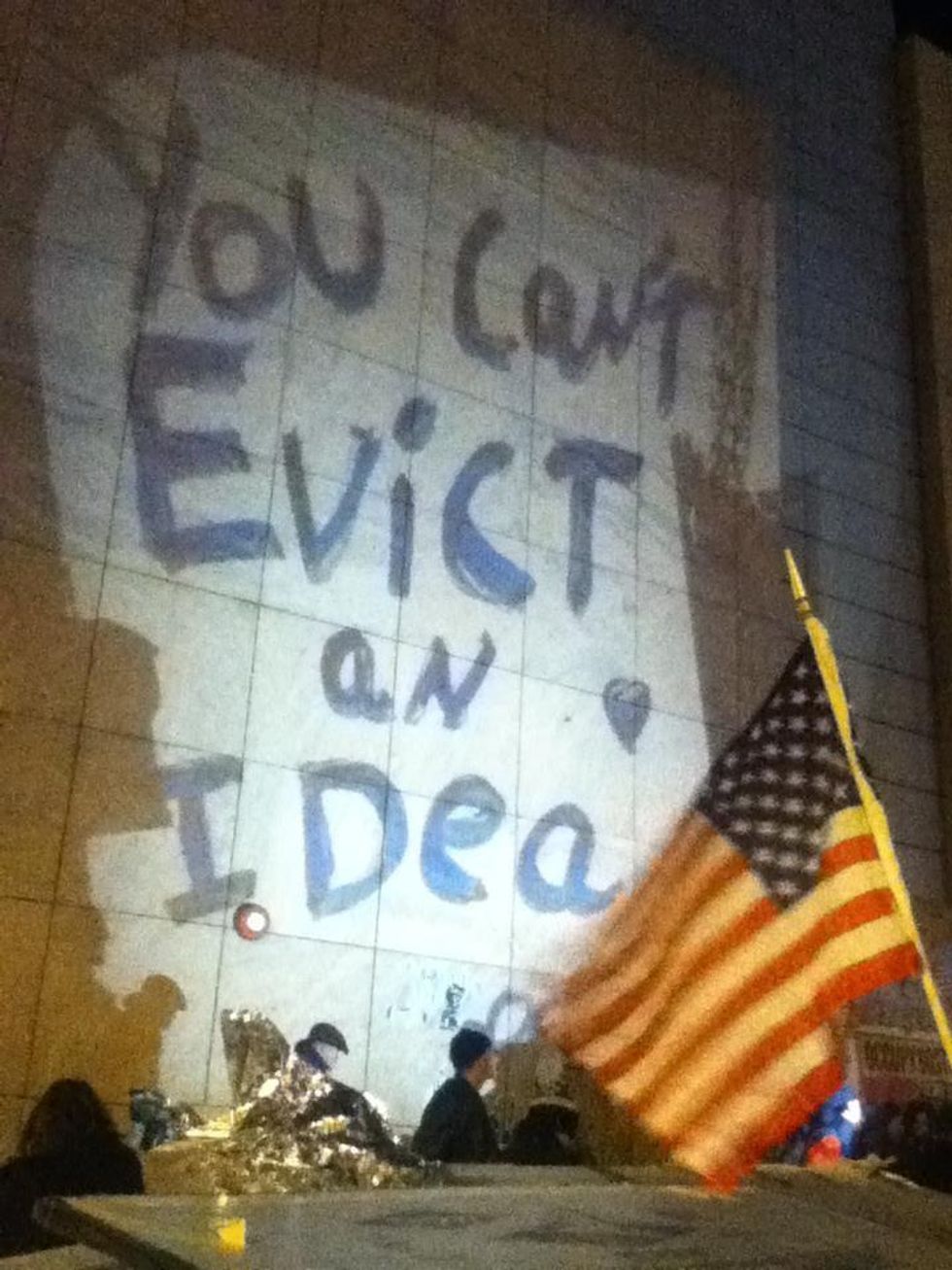

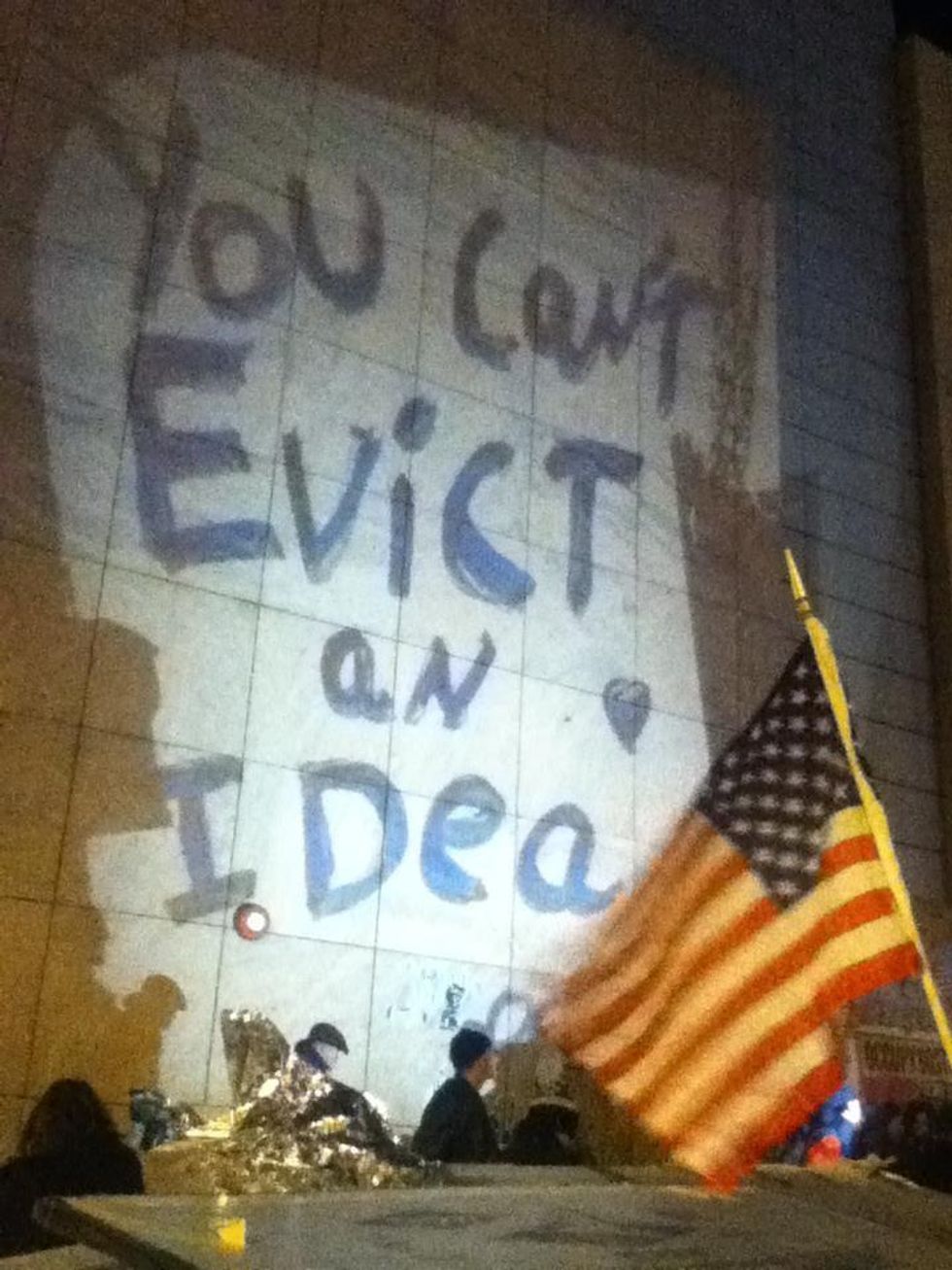

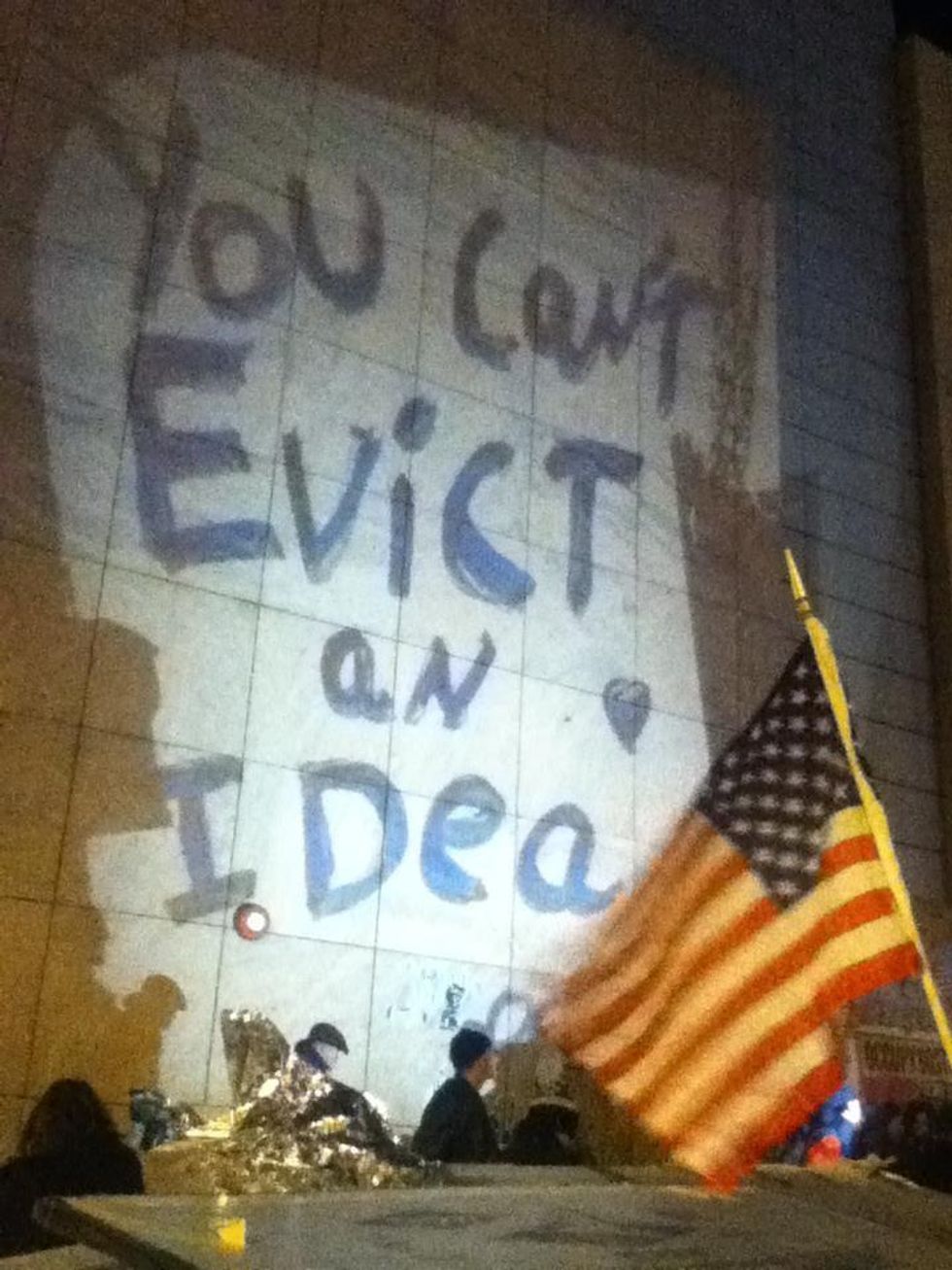

'You can't evict an idea,' read a sign posted in the window of 21-29 Sun Street, in the City of London.

The grey concrete office block, owned by the Swiss bank UBS, had been invaded and turned into a 'Bank of Ideas' by members of London's Occupy movement.

'You can't evict an idea,' read a sign posted in the window of 21-29 Sun Street, in the City of London.

The grey concrete office block, owned by the Swiss bank UBS, had been invaded and turned into a 'Bank of Ideas' by members of London's Occupy movement.

Inside, instead of screens and monitors showing the ups and downs of the markets, walls were decorated with Banksy-style graffiti art. Where there might have been a boardroom table, ping pong was being played.

Upstairs, small children were squealing. Offices once used by senior staff on six-figure salaries were now providing shelter for homeless families.

In a large room, people were gathering for a conference with the title 'Beyond Capitalism'.

Apart from the crisis in capitalism - 'utterly bankrupt at every level' as one participant put it - a recurrent theme was 'inequality'.

Fast-forward a couple of weeks to a very different gathering, at the Swiss ski resort of Davos. This is where around 2,500 of the world's political and business leaders were meeting for the World Economic Forum.

The conference this year was modestly entitled 'The Great Transformation'. Here too equality made an appearance. At the $40,000-a-head event some expressed dismay at the 'vulgarity' of bankers' outsize bonuses. Some business leaders even claimed that it was 'unsustainable' not to tackle growing inequality.

This is new. The entrenched neoliberal view has always been that inequality does not matter; the free market will make life better for everyone. Equality thinking hinders enterprise.

Why the change of tack?

One reason could be found not far from the conference centre, in a car park where a small group of Occupiers had set up a camp of igloos and yurts, a climate-adapted version of any of the 800 or so protest camps, large and small, that have popped up around the world in recent months.

Though at first disparaged as naive and directionless, the Occupy movement struck a chord with the public and got the corporate and political elites rattled.

Leaders have had to amend their rhetoric. Barack Obama and Britain's David Cameron have recently called for 'responsible capitalism' and an economy that is 'more fair'. Australia's Julia Gillard says the country can 'build a rich, fair economy'. Even US Republican hopeful Mitt Romney (a finance millionaire who pays income tax at 13 per cent) admits he is 'worried about the 99 per cent'.

The discovery of equality is not all down to the Occupy movement. Books like The Spirit Level have provided convincing academic evidence that more equal societies do better in every way. Even at the IMF, says Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, senior people are talking about equality now.

So the high-priests of capitalism are changing their tune. What about their performance?

It really did seem, for a moment in 2008, like the political and business elites had accepted that urgent action was needed to rein in the excesses of the finance sector. The banks had driven the global finance system over the edge of a cliff, and were held in suspension only by the public purse strings.

Four years later, what has been achieved?

Not a lot.

Let's hear what those people at Davos have to say about the current state of things. The reporting rules protect their anonymity in the sessions, so they are able to speak more candidly.

'Every conceivable debt is at record levels,' said one panellist. 'I just don't see how it is tenable to say that we can grow our way out of it.'

In one session a straw poll was held in which the question was asked: 'Is the financial system safer now?' Of the 140 people packed into the room, just 10 agreed. About half of them worried that it had become even worse, reported the BBC's Tim Weber.

The world is awash with debt, and we still don't really know how much of it is 'toxic'. Trading in derivatives - partly blamed for the last crisis - is going through the roof. And while traditional banking is scaling back its lending - especially to small and medium-sized business - the riskier and less regulated 'shadow banking' in the form of hedge funds, money markets and private equity, is back at its pre-crisis peak.

If the world is more unstable, it's also more unequal. The gap between rich and poor in Western economies is at its widest in 30 years, says the OECDThe gap is also growing in India, China and other parts of the Global South.

One of the unintended consequences of US quantitative easing was to flood the world with money, which caused a sharp rise in the price of food, pushing the world's poorest billion people deeper into poverty.

The super-rich, by contrast, only saw a slight dip in their fortunes. In 2009, at the height of the crisis, average Wall Street bonuses were back close to the highest in history. In 2010 Forbes magazine counted a record 1,200 billionaires in the world - up 28 per cent on 2007.

And it's not just bankers. Corporate profits in the US rose by 57 per cent in the 18 months up to the beginning of 2010. Businesses took advantage of the slump to freeze pay, cut hours and shed labour. Salary payments fell by $122 billion over the same period.

Living standards have dropped for most people in the US, Britain and the rest of Europe. Real incomes in Britain have been stagnant since 2005. In countries like Greece and Ireland they have plummeted. Homelessness is soaring. Between a quarter and a half of young people in southern Europe and North Africa cannot find jobs.

Austerity measures aimed at reducing national budget deficits have cut into public services and stymied chances of recovery. Women have been disproportionately affected, both in job losses and in their role as carers for other family members. Even Canada's welfare system is in the firing line. In Greece the suicide rate has gone up by 40 per cent in one year - prior to that the country had the lowest rate in Europe.

Legendary billionaire Warren Buffet says: 'There's class warfare, all right, but it's my class, the rich class, that's making war - and we're winning.'

A couple of years ago Nobel economist Paul Krugman noticed that just before the 2007 credit crunch the disparity in income in the US was greater than at any time since just before the Wall Street Crash in 1928. 'Coincidence or causation?' he asked.

In a new book, British economist Stewart Lansley places the issue of inequality squarely at the root of the crisis, and provides a plethora of facts and figures to back his case.

In the US in the 1960s, the gap between the pay of top executives in average companies and that of all workers was 42 to 1. By 2007 it had risen to 344 to 1. The trend is similar almost everywhere else.

But the model of economic growth and development being pursued required high levels of consumption - by everyone, including the low-paid. How to reconcile the two? Credit. Cheap, easy, plentiful credit. Have what you want now and pay later. Debt made the underpaid feel less poor than they were and sedated unrest.

At the same time governments were eager to promote the dream of home ownership. They encouraged banks to create huge amounts of mortgage debt. Even the tricky issue of selling mortgages to people who could not afford them was surmountable by using complex financial instruments.

Inequality, of almost every kind, lay at the heart of the US sub-prime mortgage bubble that finally burst in 2007. Fortunes had been made by international banks and brokers who had exploited the 'untapped market' of low-income people. The loans they had taken out had high rates of return for the lenders.

In the end it was the low-income people who were left homeless, penniless and with a blighted credit record. For ordinary folk there was no bank bailout, no quick solution. Just enduring hardship. In a single month, July 2010, a record 93,000 US homes were repossessed.

An economy based on debt not only deepens inequality. It also has a way of killing freedom and democracy - both at a personal level and at a national level.

Well-intended initiatives to introduce safeguards, like the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act in the US and the Vicker's recommendations in Britain, have been weakened by intensive lobbying from the finance sector and delay in implementation. The British plan to separate retail and investment banking is not slated to happen until 2019. That's about the time it took for the Americans to decide to put a man on the moon and to actually do it. A similar timescale applies to international agreements - under Basel III - to tighten up rules on how much capital banks need to hold.

At the time of writing, only Nicholas Sarkozy seems to be keen to move on a financial transactions (aka Tobin) tax that most EU countries agree would be a way of raising revenue, slowing down the riskiest trading and reducing market volatility. But even he is putting it off until after the French presidential election. The tax is unequivocally resisted by David Cameron, proudly defending the City of London's status as a hub for derivatives trading and the world's biggest tax haven.

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez recently announced that he would consider nationalizing any bank that refused to finance agricultural projects promoted by his government. The country's banks are required by law to provide at least 10 per cent for such public schemes.

It raises the question: why can't other leaders get tough with banks that are clearly failing in their duty to lend productively? Why can't leaders like Obama and Cameron bring the spoilt and badly behaved rotweiler of banking to heel?

The answer is simple: they don't own the dog; the dog owns them.

The ownership is partly ideological. Successive governments in Britain and the US have been captured by the idea that a large untrammelled finance sector is the key to success.

But there is another, more grubby, reason for their timidity.

The finance lobby is the richest and most powerful in the world. In the US it is the largest source of campaign contributions; since 2006 it has given more than $1.2 billion to the two main parties. In the election cycle leading to Obama's victory, bankers gave most money to the Democrats.

The top individual recipients for 2011-12, so far, are Mitt Romney ($7.8 million) and Barack Obama ($4 million). Watch out.

In Britain the ruling Conservative Party got 50 per cent of its funds from the finance sector in the election year of 2010. And we know that the 'zombie' Royal Bank of Scotland (80 per cent owned by the state) spent $4 million of British taxpayers' money lobbying in Washington to water down banking reforms aimed at making the system safer.

Writer and activist Susan George dubs the people who run the world 'the Davos class'.

'They run our major institutions, know exactly what they want, and are well organized. But they have weaknesses too. For they are wedded to an ideology that isn't working and they have virtually no ideas or imagination to resolve this.'

Fortunately, this cannot be said for the plethora of groups and individuals who are working on alternatives. There is no single magic bullet, but no shortage of ideas. We lay out some of these in Getting there: a roadmap elsewhere in Issue 450.

Many are plain common sense. For example, end casino banking and get banks to do their job: linking people who want to borrow with those who want to lend. Some, like radical Australian economist Steve Keen, argue for the nationalization of banks; Susan George prefers to talk of 'socialization' to bring them under citizen control. Regulate speculative activities and outlaw dangerous financial instruments that harm the wider economy.

Others want to reform the money system itself. 'The creation of money is too important to leave in the hands of bankers or politicians,' argues Ben Dyson from the campaign group Positive Money. They want a transparent, independent, accountable body to have that power. (Some 97 per cent of the money in the British economy is currently created by private banks through generating debt; only three per cent is issued by the state.)

Another bit of common sense: don't pay debts that aren't yours. It's something that citizens in Iceland have grasped - in two referendums they have refused to pay international debts incurred by banks and bankers. But then Iceland has let its failing banks go bust, sought money from the IMF and expanded its social safety net. The economy is now recovering. It is possible to put citizens before banks.

The Republic of Ireland took the opposite route, underwriting the debts of Anglo Irish and INBS in a hasty move that will have cost Irish citizens $60 billion and countless hardship by 2031.

Now a coalition of Irish trade unionists and NGOs has launched the 'Anglo: Not Our Debt' campaign calling for the suspension of further payments of 'this unjust debt'.

In another Irish initiative people are squatting buildings repossessed by banks that received public bailouts. Something similar is happening in the US.

A fair economy is impossible without a fair tax system and so tax justice activists around the world are exposing corporate tax dodgers, campaigning to close tax havens and the loopholes that enable rich individuals and companies to escape paying their dues.

Finally, if the politicians' concern for equality is to be believed, they will need to redirect money away from propping up the finance system and towards major programmes of education and job creation on a scale unseen since the 1930s. Many could be green jobs (see Is the Green New Deal a dead duck?, elsewhere in Issue 450) which would help countries transition to a low-carbon economy. For a fair economy has to include a more careful and equal use of the world's resources; an imperative of sustainability as opposed to profit-driven growth. It also requires recognition that the natural environment is a public good, not just an opportunity for private enterprise.

On the steps of St Paul's Cathedral a dozen people are sitting in a circle. A man called Bear lays out a large piece of paper on which he has drawn diagrams.

He is trying to improve the system of participatory democracy operating in the Occupy camp to keep it egalitarian but safeguard it from abuse by people who want to sabotage the process.

It looks complicated. They will debate for the next couple of hours, then take whatever they agree back to the General Assembly, a daily meeting open to all. Decisions are taken not by vote but by consensus, using hand signals.

This horizontal, inclusive politics is typical of the leaderless movements that have sprung up around the world - including Tahrir Square. And the elites that ignore or ridicule them do so at their peril.

Paul Mason, BBC Newsnight economics editor and author of Why It's Kicking Off Everywhere, says:

'People have had enough of, and given up on, a world run by the rich for the rich.'

In some cases even the rich have had enough, as campers at Occupy in the City of London have discovered in their conversations with city traders and bankers who drop by.

A Wall Street occupier recalls these words from a police officer arresting protesters on Brooklyn Bridge: 'I want you guys to know, I totally know where you are coming from. My family was fucked over by foreclosures and predatory loans and the banking industry being twisted, but I can't be with you guys because of the badge.'

How much longer before people like him come over... to their own side?

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

'You can't evict an idea,' read a sign posted in the window of 21-29 Sun Street, in the City of London.

The grey concrete office block, owned by the Swiss bank UBS, had been invaded and turned into a 'Bank of Ideas' by members of London's Occupy movement.

Inside, instead of screens and monitors showing the ups and downs of the markets, walls were decorated with Banksy-style graffiti art. Where there might have been a boardroom table, ping pong was being played.

Upstairs, small children were squealing. Offices once used by senior staff on six-figure salaries were now providing shelter for homeless families.

In a large room, people were gathering for a conference with the title 'Beyond Capitalism'.

Apart from the crisis in capitalism - 'utterly bankrupt at every level' as one participant put it - a recurrent theme was 'inequality'.

Fast-forward a couple of weeks to a very different gathering, at the Swiss ski resort of Davos. This is where around 2,500 of the world's political and business leaders were meeting for the World Economic Forum.

The conference this year was modestly entitled 'The Great Transformation'. Here too equality made an appearance. At the $40,000-a-head event some expressed dismay at the 'vulgarity' of bankers' outsize bonuses. Some business leaders even claimed that it was 'unsustainable' not to tackle growing inequality.

This is new. The entrenched neoliberal view has always been that inequality does not matter; the free market will make life better for everyone. Equality thinking hinders enterprise.

Why the change of tack?

One reason could be found not far from the conference centre, in a car park where a small group of Occupiers had set up a camp of igloos and yurts, a climate-adapted version of any of the 800 or so protest camps, large and small, that have popped up around the world in recent months.

Though at first disparaged as naive and directionless, the Occupy movement struck a chord with the public and got the corporate and political elites rattled.

Leaders have had to amend their rhetoric. Barack Obama and Britain's David Cameron have recently called for 'responsible capitalism' and an economy that is 'more fair'. Australia's Julia Gillard says the country can 'build a rich, fair economy'. Even US Republican hopeful Mitt Romney (a finance millionaire who pays income tax at 13 per cent) admits he is 'worried about the 99 per cent'.

The discovery of equality is not all down to the Occupy movement. Books like The Spirit Level have provided convincing academic evidence that more equal societies do better in every way. Even at the IMF, says Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, senior people are talking about equality now.

So the high-priests of capitalism are changing their tune. What about their performance?

It really did seem, for a moment in 2008, like the political and business elites had accepted that urgent action was needed to rein in the excesses of the finance sector. The banks had driven the global finance system over the edge of a cliff, and were held in suspension only by the public purse strings.

Four years later, what has been achieved?

Not a lot.

Let's hear what those people at Davos have to say about the current state of things. The reporting rules protect their anonymity in the sessions, so they are able to speak more candidly.

'Every conceivable debt is at record levels,' said one panellist. 'I just don't see how it is tenable to say that we can grow our way out of it.'

In one session a straw poll was held in which the question was asked: 'Is the financial system safer now?' Of the 140 people packed into the room, just 10 agreed. About half of them worried that it had become even worse, reported the BBC's Tim Weber.

The world is awash with debt, and we still don't really know how much of it is 'toxic'. Trading in derivatives - partly blamed for the last crisis - is going through the roof. And while traditional banking is scaling back its lending - especially to small and medium-sized business - the riskier and less regulated 'shadow banking' in the form of hedge funds, money markets and private equity, is back at its pre-crisis peak.

If the world is more unstable, it's also more unequal. The gap between rich and poor in Western economies is at its widest in 30 years, says the OECDThe gap is also growing in India, China and other parts of the Global South.

One of the unintended consequences of US quantitative easing was to flood the world with money, which caused a sharp rise in the price of food, pushing the world's poorest billion people deeper into poverty.

The super-rich, by contrast, only saw a slight dip in their fortunes. In 2009, at the height of the crisis, average Wall Street bonuses were back close to the highest in history. In 2010 Forbes magazine counted a record 1,200 billionaires in the world - up 28 per cent on 2007.

And it's not just bankers. Corporate profits in the US rose by 57 per cent in the 18 months up to the beginning of 2010. Businesses took advantage of the slump to freeze pay, cut hours and shed labour. Salary payments fell by $122 billion over the same period.

Living standards have dropped for most people in the US, Britain and the rest of Europe. Real incomes in Britain have been stagnant since 2005. In countries like Greece and Ireland they have plummeted. Homelessness is soaring. Between a quarter and a half of young people in southern Europe and North Africa cannot find jobs.

Austerity measures aimed at reducing national budget deficits have cut into public services and stymied chances of recovery. Women have been disproportionately affected, both in job losses and in their role as carers for other family members. Even Canada's welfare system is in the firing line. In Greece the suicide rate has gone up by 40 per cent in one year - prior to that the country had the lowest rate in Europe.

Legendary billionaire Warren Buffet says: 'There's class warfare, all right, but it's my class, the rich class, that's making war - and we're winning.'

A couple of years ago Nobel economist Paul Krugman noticed that just before the 2007 credit crunch the disparity in income in the US was greater than at any time since just before the Wall Street Crash in 1928. 'Coincidence or causation?' he asked.

In a new book, British economist Stewart Lansley places the issue of inequality squarely at the root of the crisis, and provides a plethora of facts and figures to back his case.

In the US in the 1960s, the gap between the pay of top executives in average companies and that of all workers was 42 to 1. By 2007 it had risen to 344 to 1. The trend is similar almost everywhere else.

But the model of economic growth and development being pursued required high levels of consumption - by everyone, including the low-paid. How to reconcile the two? Credit. Cheap, easy, plentiful credit. Have what you want now and pay later. Debt made the underpaid feel less poor than they were and sedated unrest.

At the same time governments were eager to promote the dream of home ownership. They encouraged banks to create huge amounts of mortgage debt. Even the tricky issue of selling mortgages to people who could not afford them was surmountable by using complex financial instruments.

Inequality, of almost every kind, lay at the heart of the US sub-prime mortgage bubble that finally burst in 2007. Fortunes had been made by international banks and brokers who had exploited the 'untapped market' of low-income people. The loans they had taken out had high rates of return for the lenders.

In the end it was the low-income people who were left homeless, penniless and with a blighted credit record. For ordinary folk there was no bank bailout, no quick solution. Just enduring hardship. In a single month, July 2010, a record 93,000 US homes were repossessed.

An economy based on debt not only deepens inequality. It also has a way of killing freedom and democracy - both at a personal level and at a national level.

Well-intended initiatives to introduce safeguards, like the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act in the US and the Vicker's recommendations in Britain, have been weakened by intensive lobbying from the finance sector and delay in implementation. The British plan to separate retail and investment banking is not slated to happen until 2019. That's about the time it took for the Americans to decide to put a man on the moon and to actually do it. A similar timescale applies to international agreements - under Basel III - to tighten up rules on how much capital banks need to hold.

At the time of writing, only Nicholas Sarkozy seems to be keen to move on a financial transactions (aka Tobin) tax that most EU countries agree would be a way of raising revenue, slowing down the riskiest trading and reducing market volatility. But even he is putting it off until after the French presidential election. The tax is unequivocally resisted by David Cameron, proudly defending the City of London's status as a hub for derivatives trading and the world's biggest tax haven.

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez recently announced that he would consider nationalizing any bank that refused to finance agricultural projects promoted by his government. The country's banks are required by law to provide at least 10 per cent for such public schemes.

It raises the question: why can't other leaders get tough with banks that are clearly failing in their duty to lend productively? Why can't leaders like Obama and Cameron bring the spoilt and badly behaved rotweiler of banking to heel?

The answer is simple: they don't own the dog; the dog owns them.

The ownership is partly ideological. Successive governments in Britain and the US have been captured by the idea that a large untrammelled finance sector is the key to success.

But there is another, more grubby, reason for their timidity.

The finance lobby is the richest and most powerful in the world. In the US it is the largest source of campaign contributions; since 2006 it has given more than $1.2 billion to the two main parties. In the election cycle leading to Obama's victory, bankers gave most money to the Democrats.

The top individual recipients for 2011-12, so far, are Mitt Romney ($7.8 million) and Barack Obama ($4 million). Watch out.

In Britain the ruling Conservative Party got 50 per cent of its funds from the finance sector in the election year of 2010. And we know that the 'zombie' Royal Bank of Scotland (80 per cent owned by the state) spent $4 million of British taxpayers' money lobbying in Washington to water down banking reforms aimed at making the system safer.

Writer and activist Susan George dubs the people who run the world 'the Davos class'.

'They run our major institutions, know exactly what they want, and are well organized. But they have weaknesses too. For they are wedded to an ideology that isn't working and they have virtually no ideas or imagination to resolve this.'

Fortunately, this cannot be said for the plethora of groups and individuals who are working on alternatives. There is no single magic bullet, but no shortage of ideas. We lay out some of these in Getting there: a roadmap elsewhere in Issue 450.

Many are plain common sense. For example, end casino banking and get banks to do their job: linking people who want to borrow with those who want to lend. Some, like radical Australian economist Steve Keen, argue for the nationalization of banks; Susan George prefers to talk of 'socialization' to bring them under citizen control. Regulate speculative activities and outlaw dangerous financial instruments that harm the wider economy.

Others want to reform the money system itself. 'The creation of money is too important to leave in the hands of bankers or politicians,' argues Ben Dyson from the campaign group Positive Money. They want a transparent, independent, accountable body to have that power. (Some 97 per cent of the money in the British economy is currently created by private banks through generating debt; only three per cent is issued by the state.)

Another bit of common sense: don't pay debts that aren't yours. It's something that citizens in Iceland have grasped - in two referendums they have refused to pay international debts incurred by banks and bankers. But then Iceland has let its failing banks go bust, sought money from the IMF and expanded its social safety net. The economy is now recovering. It is possible to put citizens before banks.

The Republic of Ireland took the opposite route, underwriting the debts of Anglo Irish and INBS in a hasty move that will have cost Irish citizens $60 billion and countless hardship by 2031.

Now a coalition of Irish trade unionists and NGOs has launched the 'Anglo: Not Our Debt' campaign calling for the suspension of further payments of 'this unjust debt'.

In another Irish initiative people are squatting buildings repossessed by banks that received public bailouts. Something similar is happening in the US.

A fair economy is impossible without a fair tax system and so tax justice activists around the world are exposing corporate tax dodgers, campaigning to close tax havens and the loopholes that enable rich individuals and companies to escape paying their dues.

Finally, if the politicians' concern for equality is to be believed, they will need to redirect money away from propping up the finance system and towards major programmes of education and job creation on a scale unseen since the 1930s. Many could be green jobs (see Is the Green New Deal a dead duck?, elsewhere in Issue 450) which would help countries transition to a low-carbon economy. For a fair economy has to include a more careful and equal use of the world's resources; an imperative of sustainability as opposed to profit-driven growth. It also requires recognition that the natural environment is a public good, not just an opportunity for private enterprise.

On the steps of St Paul's Cathedral a dozen people are sitting in a circle. A man called Bear lays out a large piece of paper on which he has drawn diagrams.

He is trying to improve the system of participatory democracy operating in the Occupy camp to keep it egalitarian but safeguard it from abuse by people who want to sabotage the process.

It looks complicated. They will debate for the next couple of hours, then take whatever they agree back to the General Assembly, a daily meeting open to all. Decisions are taken not by vote but by consensus, using hand signals.

This horizontal, inclusive politics is typical of the leaderless movements that have sprung up around the world - including Tahrir Square. And the elites that ignore or ridicule them do so at their peril.

Paul Mason, BBC Newsnight economics editor and author of Why It's Kicking Off Everywhere, says:

'People have had enough of, and given up on, a world run by the rich for the rich.'

In some cases even the rich have had enough, as campers at Occupy in the City of London have discovered in their conversations with city traders and bankers who drop by.

A Wall Street occupier recalls these words from a police officer arresting protesters on Brooklyn Bridge: 'I want you guys to know, I totally know where you are coming from. My family was fucked over by foreclosures and predatory loans and the banking industry being twisted, but I can't be with you guys because of the badge.'

How much longer before people like him come over... to their own side?

'You can't evict an idea,' read a sign posted in the window of 21-29 Sun Street, in the City of London.

The grey concrete office block, owned by the Swiss bank UBS, had been invaded and turned into a 'Bank of Ideas' by members of London's Occupy movement.

Inside, instead of screens and monitors showing the ups and downs of the markets, walls were decorated with Banksy-style graffiti art. Where there might have been a boardroom table, ping pong was being played.

Upstairs, small children were squealing. Offices once used by senior staff on six-figure salaries were now providing shelter for homeless families.

In a large room, people were gathering for a conference with the title 'Beyond Capitalism'.

Apart from the crisis in capitalism - 'utterly bankrupt at every level' as one participant put it - a recurrent theme was 'inequality'.

Fast-forward a couple of weeks to a very different gathering, at the Swiss ski resort of Davos. This is where around 2,500 of the world's political and business leaders were meeting for the World Economic Forum.

The conference this year was modestly entitled 'The Great Transformation'. Here too equality made an appearance. At the $40,000-a-head event some expressed dismay at the 'vulgarity' of bankers' outsize bonuses. Some business leaders even claimed that it was 'unsustainable' not to tackle growing inequality.

This is new. The entrenched neoliberal view has always been that inequality does not matter; the free market will make life better for everyone. Equality thinking hinders enterprise.

Why the change of tack?

One reason could be found not far from the conference centre, in a car park where a small group of Occupiers had set up a camp of igloos and yurts, a climate-adapted version of any of the 800 or so protest camps, large and small, that have popped up around the world in recent months.

Though at first disparaged as naive and directionless, the Occupy movement struck a chord with the public and got the corporate and political elites rattled.

Leaders have had to amend their rhetoric. Barack Obama and Britain's David Cameron have recently called for 'responsible capitalism' and an economy that is 'more fair'. Australia's Julia Gillard says the country can 'build a rich, fair economy'. Even US Republican hopeful Mitt Romney (a finance millionaire who pays income tax at 13 per cent) admits he is 'worried about the 99 per cent'.

The discovery of equality is not all down to the Occupy movement. Books like The Spirit Level have provided convincing academic evidence that more equal societies do better in every way. Even at the IMF, says Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, senior people are talking about equality now.

So the high-priests of capitalism are changing their tune. What about their performance?

It really did seem, for a moment in 2008, like the political and business elites had accepted that urgent action was needed to rein in the excesses of the finance sector. The banks had driven the global finance system over the edge of a cliff, and were held in suspension only by the public purse strings.

Four years later, what has been achieved?

Not a lot.

Let's hear what those people at Davos have to say about the current state of things. The reporting rules protect their anonymity in the sessions, so they are able to speak more candidly.

'Every conceivable debt is at record levels,' said one panellist. 'I just don't see how it is tenable to say that we can grow our way out of it.'

In one session a straw poll was held in which the question was asked: 'Is the financial system safer now?' Of the 140 people packed into the room, just 10 agreed. About half of them worried that it had become even worse, reported the BBC's Tim Weber.

The world is awash with debt, and we still don't really know how much of it is 'toxic'. Trading in derivatives - partly blamed for the last crisis - is going through the roof. And while traditional banking is scaling back its lending - especially to small and medium-sized business - the riskier and less regulated 'shadow banking' in the form of hedge funds, money markets and private equity, is back at its pre-crisis peak.

If the world is more unstable, it's also more unequal. The gap between rich and poor in Western economies is at its widest in 30 years, says the OECDThe gap is also growing in India, China and other parts of the Global South.

One of the unintended consequences of US quantitative easing was to flood the world with money, which caused a sharp rise in the price of food, pushing the world's poorest billion people deeper into poverty.

The super-rich, by contrast, only saw a slight dip in their fortunes. In 2009, at the height of the crisis, average Wall Street bonuses were back close to the highest in history. In 2010 Forbes magazine counted a record 1,200 billionaires in the world - up 28 per cent on 2007.

And it's not just bankers. Corporate profits in the US rose by 57 per cent in the 18 months up to the beginning of 2010. Businesses took advantage of the slump to freeze pay, cut hours and shed labour. Salary payments fell by $122 billion over the same period.

Living standards have dropped for most people in the US, Britain and the rest of Europe. Real incomes in Britain have been stagnant since 2005. In countries like Greece and Ireland they have plummeted. Homelessness is soaring. Between a quarter and a half of young people in southern Europe and North Africa cannot find jobs.

Austerity measures aimed at reducing national budget deficits have cut into public services and stymied chances of recovery. Women have been disproportionately affected, both in job losses and in their role as carers for other family members. Even Canada's welfare system is in the firing line. In Greece the suicide rate has gone up by 40 per cent in one year - prior to that the country had the lowest rate in Europe.

Legendary billionaire Warren Buffet says: 'There's class warfare, all right, but it's my class, the rich class, that's making war - and we're winning.'

A couple of years ago Nobel economist Paul Krugman noticed that just before the 2007 credit crunch the disparity in income in the US was greater than at any time since just before the Wall Street Crash in 1928. 'Coincidence or causation?' he asked.

In a new book, British economist Stewart Lansley places the issue of inequality squarely at the root of the crisis, and provides a plethora of facts and figures to back his case.

In the US in the 1960s, the gap between the pay of top executives in average companies and that of all workers was 42 to 1. By 2007 it had risen to 344 to 1. The trend is similar almost everywhere else.

But the model of economic growth and development being pursued required high levels of consumption - by everyone, including the low-paid. How to reconcile the two? Credit. Cheap, easy, plentiful credit. Have what you want now and pay later. Debt made the underpaid feel less poor than they were and sedated unrest.

At the same time governments were eager to promote the dream of home ownership. They encouraged banks to create huge amounts of mortgage debt. Even the tricky issue of selling mortgages to people who could not afford them was surmountable by using complex financial instruments.

Inequality, of almost every kind, lay at the heart of the US sub-prime mortgage bubble that finally burst in 2007. Fortunes had been made by international banks and brokers who had exploited the 'untapped market' of low-income people. The loans they had taken out had high rates of return for the lenders.

In the end it was the low-income people who were left homeless, penniless and with a blighted credit record. For ordinary folk there was no bank bailout, no quick solution. Just enduring hardship. In a single month, July 2010, a record 93,000 US homes were repossessed.

An economy based on debt not only deepens inequality. It also has a way of killing freedom and democracy - both at a personal level and at a national level.

Well-intended initiatives to introduce safeguards, like the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act in the US and the Vicker's recommendations in Britain, have been weakened by intensive lobbying from the finance sector and delay in implementation. The British plan to separate retail and investment banking is not slated to happen until 2019. That's about the time it took for the Americans to decide to put a man on the moon and to actually do it. A similar timescale applies to international agreements - under Basel III - to tighten up rules on how much capital banks need to hold.

At the time of writing, only Nicholas Sarkozy seems to be keen to move on a financial transactions (aka Tobin) tax that most EU countries agree would be a way of raising revenue, slowing down the riskiest trading and reducing market volatility. But even he is putting it off until after the French presidential election. The tax is unequivocally resisted by David Cameron, proudly defending the City of London's status as a hub for derivatives trading and the world's biggest tax haven.

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez recently announced that he would consider nationalizing any bank that refused to finance agricultural projects promoted by his government. The country's banks are required by law to provide at least 10 per cent for such public schemes.

It raises the question: why can't other leaders get tough with banks that are clearly failing in their duty to lend productively? Why can't leaders like Obama and Cameron bring the spoilt and badly behaved rotweiler of banking to heel?

The answer is simple: they don't own the dog; the dog owns them.

The ownership is partly ideological. Successive governments in Britain and the US have been captured by the idea that a large untrammelled finance sector is the key to success.

But there is another, more grubby, reason for their timidity.

The finance lobby is the richest and most powerful in the world. In the US it is the largest source of campaign contributions; since 2006 it has given more than $1.2 billion to the two main parties. In the election cycle leading to Obama's victory, bankers gave most money to the Democrats.

The top individual recipients for 2011-12, so far, are Mitt Romney ($7.8 million) and Barack Obama ($4 million). Watch out.

In Britain the ruling Conservative Party got 50 per cent of its funds from the finance sector in the election year of 2010. And we know that the 'zombie' Royal Bank of Scotland (80 per cent owned by the state) spent $4 million of British taxpayers' money lobbying in Washington to water down banking reforms aimed at making the system safer.

Writer and activist Susan George dubs the people who run the world 'the Davos class'.

'They run our major institutions, know exactly what they want, and are well organized. But they have weaknesses too. For they are wedded to an ideology that isn't working and they have virtually no ideas or imagination to resolve this.'

Fortunately, this cannot be said for the plethora of groups and individuals who are working on alternatives. There is no single magic bullet, but no shortage of ideas. We lay out some of these in Getting there: a roadmap elsewhere in Issue 450.

Many are plain common sense. For example, end casino banking and get banks to do their job: linking people who want to borrow with those who want to lend. Some, like radical Australian economist Steve Keen, argue for the nationalization of banks; Susan George prefers to talk of 'socialization' to bring them under citizen control. Regulate speculative activities and outlaw dangerous financial instruments that harm the wider economy.

Others want to reform the money system itself. 'The creation of money is too important to leave in the hands of bankers or politicians,' argues Ben Dyson from the campaign group Positive Money. They want a transparent, independent, accountable body to have that power. (Some 97 per cent of the money in the British economy is currently created by private banks through generating debt; only three per cent is issued by the state.)

Another bit of common sense: don't pay debts that aren't yours. It's something that citizens in Iceland have grasped - in two referendums they have refused to pay international debts incurred by banks and bankers. But then Iceland has let its failing banks go bust, sought money from the IMF and expanded its social safety net. The economy is now recovering. It is possible to put citizens before banks.

The Republic of Ireland took the opposite route, underwriting the debts of Anglo Irish and INBS in a hasty move that will have cost Irish citizens $60 billion and countless hardship by 2031.

Now a coalition of Irish trade unionists and NGOs has launched the 'Anglo: Not Our Debt' campaign calling for the suspension of further payments of 'this unjust debt'.

In another Irish initiative people are squatting buildings repossessed by banks that received public bailouts. Something similar is happening in the US.

A fair economy is impossible without a fair tax system and so tax justice activists around the world are exposing corporate tax dodgers, campaigning to close tax havens and the loopholes that enable rich individuals and companies to escape paying their dues.

Finally, if the politicians' concern for equality is to be believed, they will need to redirect money away from propping up the finance system and towards major programmes of education and job creation on a scale unseen since the 1930s. Many could be green jobs (see Is the Green New Deal a dead duck?, elsewhere in Issue 450) which would help countries transition to a low-carbon economy. For a fair economy has to include a more careful and equal use of the world's resources; an imperative of sustainability as opposed to profit-driven growth. It also requires recognition that the natural environment is a public good, not just an opportunity for private enterprise.

On the steps of St Paul's Cathedral a dozen people are sitting in a circle. A man called Bear lays out a large piece of paper on which he has drawn diagrams.

He is trying to improve the system of participatory democracy operating in the Occupy camp to keep it egalitarian but safeguard it from abuse by people who want to sabotage the process.

It looks complicated. They will debate for the next couple of hours, then take whatever they agree back to the General Assembly, a daily meeting open to all. Decisions are taken not by vote but by consensus, using hand signals.

This horizontal, inclusive politics is typical of the leaderless movements that have sprung up around the world - including Tahrir Square. And the elites that ignore or ridicule them do so at their peril.

Paul Mason, BBC Newsnight economics editor and author of Why It's Kicking Off Everywhere, says:

'People have had enough of, and given up on, a world run by the rich for the rich.'

In some cases even the rich have had enough, as campers at Occupy in the City of London have discovered in their conversations with city traders and bankers who drop by.

A Wall Street occupier recalls these words from a police officer arresting protesters on Brooklyn Bridge: 'I want you guys to know, I totally know where you are coming from. My family was fucked over by foreclosures and predatory loans and the banking industry being twisted, but I can't be with you guys because of the badge.'

How much longer before people like him come over... to their own side?