Large Hydropower: Sustainability Without Human Rights?

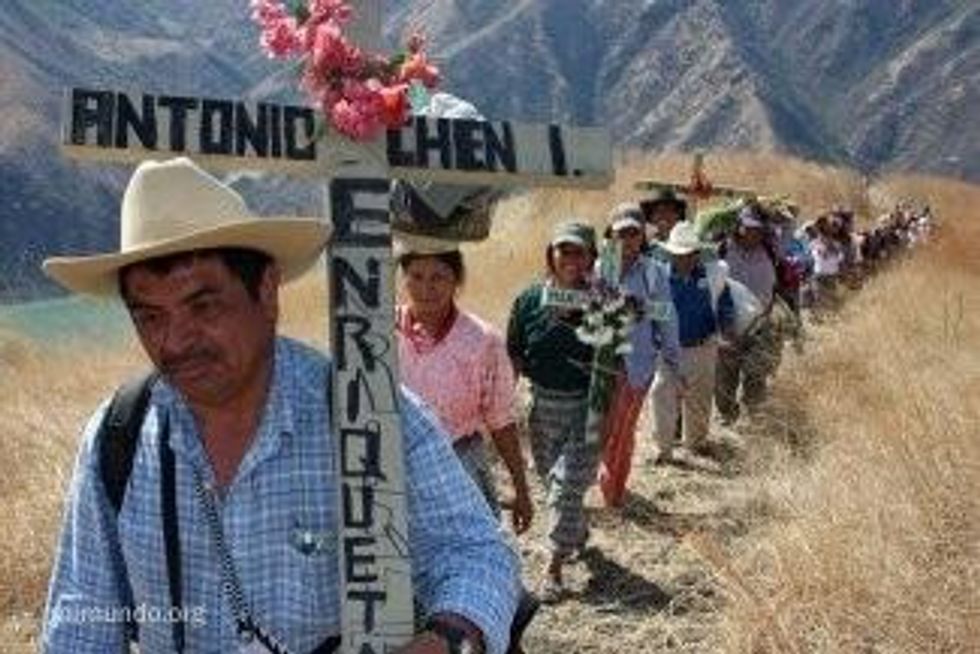

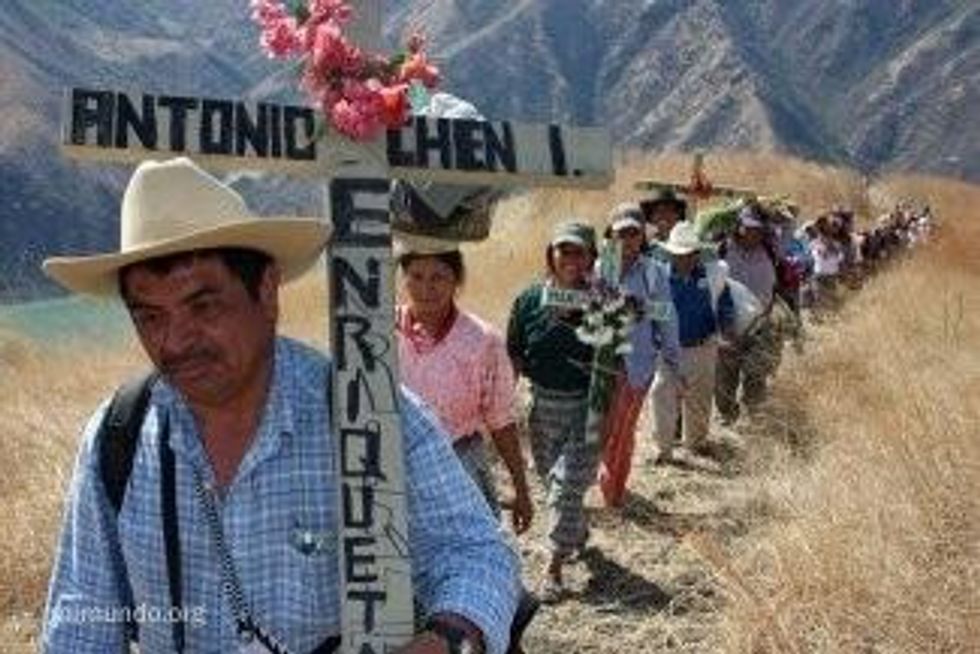

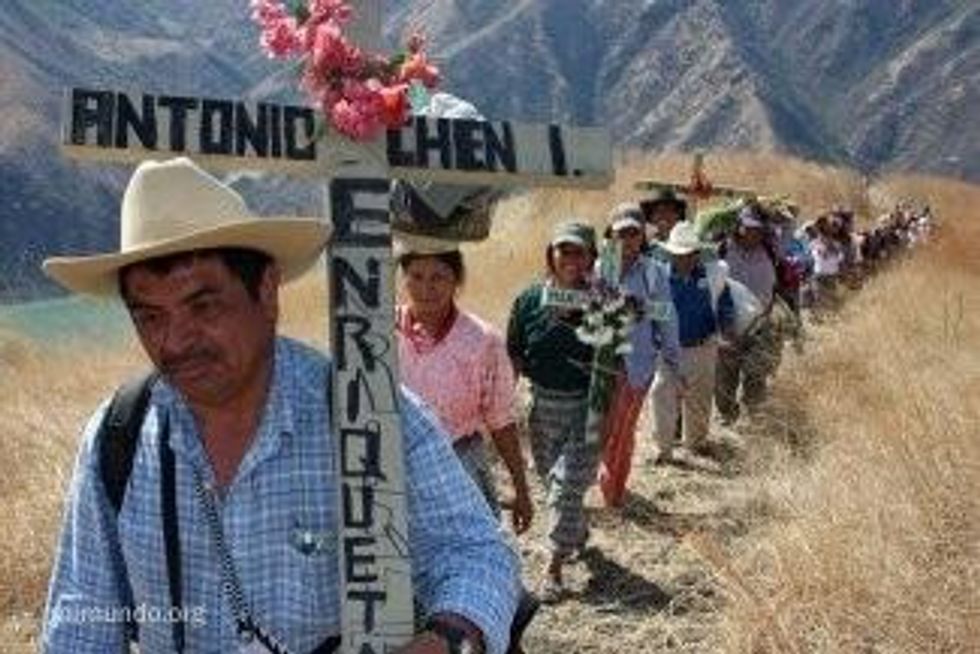

Dam projects often lead to resource conflicts between governments, private investors and local communities, and have caused a long series of human rights violations. In the most egregious case, more than 400 indigenous women and children were massacred for the construction of the Chixoy Dam in Guatemala in the 1970s. Since then, scores of dam fighters have been murdered in Brazil, Burma, China, Colombia, Ecuador, India, Mexico, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sudan, Thailand and other countries. In many cases, the victims were indigenous activists defending their ancient lands.

When we raise human rights violations with the companies building these projects, they usually try to shift all responsibility to the host governments. I have only seen one company respond to serious human rights abuses in a hydropower project, when the ABB Corporation proposed a rather half-hearted dialogue among the different interest groups after several activists were killed in the Merowe Dam Project in Sudan. In another case, industry representatives protested against the death threats against an indigenous activist from the Philippines.

The International Hydropower Association (IHA) prepared its first set of sustainability guidelines in 2003. These guidelines remained completely silent on the protection of human rights. The IHA also rejected the rights-based approach which the independent World Commission on Dams had recommended for dam projects as "heavily legalistic" and a "lawyer's dream."

In recent years, there has been a growing global consensus that companies have a direct responsibility for respecting human rights. As the UN Human Rights Council recognized last month, this responsibility goes beyond following national laws, and requires "taking adequate measures" for the "prevention, mitigation and, where appropriate, remediation" of human rights violations. Companies for example have an obligation to carry out human rights assessments before engaging in sensitive projects. The UN General Assembly and many other institutions have also recognized the right of indigenous communities to free, prior and informed consent regarding projects on their lands.

At the end of 2010, the IHA replaced its guidelines with a new tool for the assessment of hydropower projects, the Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol. This document recognizes that "sustainable development embodies (...) respecting human rights." Even though the IHA itself does not agree with this, the protocol acknowledges that respecting the consent of indigenous peoples is "proven best practice" for hydropower projects. Yet it does not define any minimum requirements - such as compliance with indigenous rights and other human rights conventions - that projects have to meet to be considered acceptable.

Ethiopia is a hotspot of human rights violations in dam projects - and a sad example of the complete disregard of the hydropower industry for these abuses. The government is building a dam on the Omo River which will devastate the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of indigenous people, and has just launched another multi-billion dollar scheme on the Blue Nile. The authorities don't allow any dissent on these projects, and many dam-affected people, NGO activists, journalists and other experts have been intimidated, jailed, or forced into exile. Even our office has received death threats over our work to stop the destructive Gibe III Dam on the Omo River. A report by Human Rights Watch has found that human rights violations in Ethiopian development projects are standard practice beyond the hydropower sector.

The Italian and Chinese companies which are building the biggest Ethiopian dams have consistently defended the government's approach. Now the International Hydropower Association has joined them. A few months ago, the industry association organized an international conference with the Ethiopian government under the motto of Hydropower for Sustainable Development. In his opening address, Prime Minister Meles Zenawi lashed out against environmental activists, whom he branded as "extremists" and "bordering on the criminal." On the day after this attack, the IHA embraced Ethiopia's dam building authority as a "Sustainability Partner." It also announced the establishment of a "centre of excellence on sustainable hydropower" in the country.

Dialogues with repressive regimes can be justified if they bring about progress for human rights and the environment. But you need a long spoon when you sup with the devil, and define clear expectations if you partner with repressive regimes. The IHA has not done so. Dam builders don't have to fulfill any social or environmental minimum standards to become its "Sustainability Partners." All they have to do is evaluate one of their projects under the dam industry's new assessment protocol over the next three years, and pay a fee to the IHA.

The international hydropower industry has missed a chance to accept its responsibility for the respect for human rights. By embracing repressive dam builders as "Sustainability Partners," it allows them to greenwash their image in an international arena while silencing their critics at home. Yet partnership cuts both ways. With bedfellows like the Ethiopian dam building authority, the IHA has put its own legitimacy on the line.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Dam projects often lead to resource conflicts between governments, private investors and local communities, and have caused a long series of human rights violations. In the most egregious case, more than 400 indigenous women and children were massacred for the construction of the Chixoy Dam in Guatemala in the 1970s. Since then, scores of dam fighters have been murdered in Brazil, Burma, China, Colombia, Ecuador, India, Mexico, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sudan, Thailand and other countries. In many cases, the victims were indigenous activists defending their ancient lands.

When we raise human rights violations with the companies building these projects, they usually try to shift all responsibility to the host governments. I have only seen one company respond to serious human rights abuses in a hydropower project, when the ABB Corporation proposed a rather half-hearted dialogue among the different interest groups after several activists were killed in the Merowe Dam Project in Sudan. In another case, industry representatives protested against the death threats against an indigenous activist from the Philippines.

The International Hydropower Association (IHA) prepared its first set of sustainability guidelines in 2003. These guidelines remained completely silent on the protection of human rights. The IHA also rejected the rights-based approach which the independent World Commission on Dams had recommended for dam projects as "heavily legalistic" and a "lawyer's dream."

In recent years, there has been a growing global consensus that companies have a direct responsibility for respecting human rights. As the UN Human Rights Council recognized last month, this responsibility goes beyond following national laws, and requires "taking adequate measures" for the "prevention, mitigation and, where appropriate, remediation" of human rights violations. Companies for example have an obligation to carry out human rights assessments before engaging in sensitive projects. The UN General Assembly and many other institutions have also recognized the right of indigenous communities to free, prior and informed consent regarding projects on their lands.

At the end of 2010, the IHA replaced its guidelines with a new tool for the assessment of hydropower projects, the Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol. This document recognizes that "sustainable development embodies (...) respecting human rights." Even though the IHA itself does not agree with this, the protocol acknowledges that respecting the consent of indigenous peoples is "proven best practice" for hydropower projects. Yet it does not define any minimum requirements - such as compliance with indigenous rights and other human rights conventions - that projects have to meet to be considered acceptable.

Ethiopia is a hotspot of human rights violations in dam projects - and a sad example of the complete disregard of the hydropower industry for these abuses. The government is building a dam on the Omo River which will devastate the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of indigenous people, and has just launched another multi-billion dollar scheme on the Blue Nile. The authorities don't allow any dissent on these projects, and many dam-affected people, NGO activists, journalists and other experts have been intimidated, jailed, or forced into exile. Even our office has received death threats over our work to stop the destructive Gibe III Dam on the Omo River. A report by Human Rights Watch has found that human rights violations in Ethiopian development projects are standard practice beyond the hydropower sector.

The Italian and Chinese companies which are building the biggest Ethiopian dams have consistently defended the government's approach. Now the International Hydropower Association has joined them. A few months ago, the industry association organized an international conference with the Ethiopian government under the motto of Hydropower for Sustainable Development. In his opening address, Prime Minister Meles Zenawi lashed out against environmental activists, whom he branded as "extremists" and "bordering on the criminal." On the day after this attack, the IHA embraced Ethiopia's dam building authority as a "Sustainability Partner." It also announced the establishment of a "centre of excellence on sustainable hydropower" in the country.

Dialogues with repressive regimes can be justified if they bring about progress for human rights and the environment. But you need a long spoon when you sup with the devil, and define clear expectations if you partner with repressive regimes. The IHA has not done so. Dam builders don't have to fulfill any social or environmental minimum standards to become its "Sustainability Partners." All they have to do is evaluate one of their projects under the dam industry's new assessment protocol over the next three years, and pay a fee to the IHA.

The international hydropower industry has missed a chance to accept its responsibility for the respect for human rights. By embracing repressive dam builders as "Sustainability Partners," it allows them to greenwash their image in an international arena while silencing their critics at home. Yet partnership cuts both ways. With bedfellows like the Ethiopian dam building authority, the IHA has put its own legitimacy on the line.

Dam projects often lead to resource conflicts between governments, private investors and local communities, and have caused a long series of human rights violations. In the most egregious case, more than 400 indigenous women and children were massacred for the construction of the Chixoy Dam in Guatemala in the 1970s. Since then, scores of dam fighters have been murdered in Brazil, Burma, China, Colombia, Ecuador, India, Mexico, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sudan, Thailand and other countries. In many cases, the victims were indigenous activists defending their ancient lands.

When we raise human rights violations with the companies building these projects, they usually try to shift all responsibility to the host governments. I have only seen one company respond to serious human rights abuses in a hydropower project, when the ABB Corporation proposed a rather half-hearted dialogue among the different interest groups after several activists were killed in the Merowe Dam Project in Sudan. In another case, industry representatives protested against the death threats against an indigenous activist from the Philippines.

The International Hydropower Association (IHA) prepared its first set of sustainability guidelines in 2003. These guidelines remained completely silent on the protection of human rights. The IHA also rejected the rights-based approach which the independent World Commission on Dams had recommended for dam projects as "heavily legalistic" and a "lawyer's dream."

In recent years, there has been a growing global consensus that companies have a direct responsibility for respecting human rights. As the UN Human Rights Council recognized last month, this responsibility goes beyond following national laws, and requires "taking adequate measures" for the "prevention, mitigation and, where appropriate, remediation" of human rights violations. Companies for example have an obligation to carry out human rights assessments before engaging in sensitive projects. The UN General Assembly and many other institutions have also recognized the right of indigenous communities to free, prior and informed consent regarding projects on their lands.

At the end of 2010, the IHA replaced its guidelines with a new tool for the assessment of hydropower projects, the Hydropower Sustainability Assessment Protocol. This document recognizes that "sustainable development embodies (...) respecting human rights." Even though the IHA itself does not agree with this, the protocol acknowledges that respecting the consent of indigenous peoples is "proven best practice" for hydropower projects. Yet it does not define any minimum requirements - such as compliance with indigenous rights and other human rights conventions - that projects have to meet to be considered acceptable.

Ethiopia is a hotspot of human rights violations in dam projects - and a sad example of the complete disregard of the hydropower industry for these abuses. The government is building a dam on the Omo River which will devastate the livelihoods of hundreds of thousands of indigenous people, and has just launched another multi-billion dollar scheme on the Blue Nile. The authorities don't allow any dissent on these projects, and many dam-affected people, NGO activists, journalists and other experts have been intimidated, jailed, or forced into exile. Even our office has received death threats over our work to stop the destructive Gibe III Dam on the Omo River. A report by Human Rights Watch has found that human rights violations in Ethiopian development projects are standard practice beyond the hydropower sector.

The Italian and Chinese companies which are building the biggest Ethiopian dams have consistently defended the government's approach. Now the International Hydropower Association has joined them. A few months ago, the industry association organized an international conference with the Ethiopian government under the motto of Hydropower for Sustainable Development. In his opening address, Prime Minister Meles Zenawi lashed out against environmental activists, whom he branded as "extremists" and "bordering on the criminal." On the day after this attack, the IHA embraced Ethiopia's dam building authority as a "Sustainability Partner." It also announced the establishment of a "centre of excellence on sustainable hydropower" in the country.

Dialogues with repressive regimes can be justified if they bring about progress for human rights and the environment. But you need a long spoon when you sup with the devil, and define clear expectations if you partner with repressive regimes. The IHA has not done so. Dam builders don't have to fulfill any social or environmental minimum standards to become its "Sustainability Partners." All they have to do is evaluate one of their projects under the dam industry's new assessment protocol over the next three years, and pay a fee to the IHA.

The international hydropower industry has missed a chance to accept its responsibility for the respect for human rights. By embracing repressive dam builders as "Sustainability Partners," it allows them to greenwash their image in an international arena while silencing their critics at home. Yet partnership cuts both ways. With bedfellows like the Ethiopian dam building authority, the IHA has put its own legitimacy on the line.