SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

The former senator’s continuing prominence in debates over nuclear policy is a testament to our historical amnesia about the risks posed by nuclear weapons.

A primary responsibility of the government is, of course, to keep us safe. Given that obligation, you might think that the Washington establishment would be hard at work trying to prevent the ultimate catastrophe—a nuclear war. But you would be wrong.

A small, hardworking contingent of elected officials is indeed trying to roll back the nuclear arms race and make it harder for such world-ending weaponry ever to be used again, including stalwarts like Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), Rep. John Garamendi (D-Calif.), and other members of the Congressional Nuclear Weapons and Arms Control Working Group. But they face ever stiffer headwinds from a resurgent network of nuclear hawks who want to build more kinds of nuclear weapons and ever more of them. And mind you, that would all be in addition to the Pentagon’s current plans for spending up to $2 trillion over the next three decades to create a whole new generation of nuclear weapons, stoking a dangerous new nuclear arms race.

There are many drivers of this push for a larger, more dangerous arsenal—from the misguided notion that more nuclear weapons will make us safer to an entrenched network of companies, governmental institutions, members of Congress, and policy pundits who will profit (directly or indirectly) from an accelerated nuclear arms race. One indicator of the current state of affairs is the resurgence of former Arizona Sen. Jon Kyl, who spent 18 years in Congress opposing even the most modest efforts to control nuclear weapons before he went on to work as a lobbyist and policy advocate for the nuclear weapons complex.

His continuing prominence in debates over nuclear policy—evidenced most recently by his position as vice chair of a congressionally appointed commission that sought to legitimize an across-the-board nuclear buildup—is a testament to our historical amnesia about the risks posed by nuclear weapons.

Republican Jon Kyl was elected to the Senate from Arizona in 1995 and served in that body until 2013, plus a brief stint in late 2018 to fill out the term of the late Sen. John McCain.

One of Kyl’s signature accomplishments in his early years in office was his role in lobbying fellow Republican senators to vote against ratifying the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), which went down to a 51 to 48 Senate defeat in October 1999. That treaty banned explosive nuclear testing and included monitoring and verification procedures meant to ensure that its members met their obligations. Had it been widely adopted, it might have slowed the spread of nuclear weapons, now possessed by nine countries, and prevented a return to the days when aboveground testing spread cancer-causing radiation to downwind communities.

The defeat of the CTBT marked the beginning of a decades-long process of dismantling the global nuclear arms control system, launched by the December 2001 withdrawal of President George W. Bush’s administration from the Nixon-era Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty. That treaty was designed to prevent a “defense-offense” nuclear arms race in which one side’s pursuit of anti-missile defenses sparks the other side to build more—and ever more capable—nuclear-armed missiles. James Acton of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace called the withdrawal from the ABM Treaty an “epic mistake” that fueled a new nuclear arms race. Kyl argued otherwise, claiming the withdrawal removed “a straitjacket from our national security.”

The truly naive ones are the nuclear hawks who insist on clinging to the dubious notion that vast (and still spreading) stores of nuclear weaponry can be kept around indefinitely without ever being used again, by accident or design.

The end of the ABM treaty created the worst of both worlds—an incentive for adversaries to build up their nuclear arsenals coupled with an abject failure to develop weaponry that could actually defend the United States in the event of a real-world nuclear attack.

Then, in August 2019, during the first Trump administration, the U.S. withdrew from the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty, which prohibited the deployment of medium-range missiles with ranges of 500 to 5,500 kilometers. That treaty had been particularly important because it eliminated the danger of having missiles in Europe that could reach their targets in a very brief time frame, a situation that could shorten the trigger on a possible nuclear confrontation.

Then-Sen. Kyl also used the eventual pullout from the INF treaty as a reason to exit yet another nuclear agreement, the New START treaty, co-signing a letter with 24 of his colleagues urging the Trump administration to reject New START. He was basically suggesting that lifting one set of safeguards against a possible nuclear confrontation was somehow a reason to junk a separate treaty that had ensured some stability in the U.S.-Russian strategic nuclear balance.

Finally, in November 2023, NATO suspended its observance of a treaty that had limited the number of troops the Western alliance and Russia could deploy in Europe after the government of Vladimir Putin withdrew from the treaty earlier that year in the midst of his ongoing invasion of Ukraine.

The last U.S.-Russian arms control agreement, New START, caps the strategic nuclear warheads of the two countries at 1,550 each and has monitoring mechanisms to make sure each side is holding up its obligations. That treaty is currently hanging by a thread. It expires in 2026, and there is no indication that Russia is inclined to negotiate an extension in the context of its current state of relations with Washington.

As early as December 2020, Kyl was angling to get the government to abandon any plans to extend New START, coauthoring an op-ed on the subject for the Fox News website. He naturally ignored the benefits of an agreement aimed at reducing the chance of an accidental nuclear conflict, even as he made misleading statements about it being unbalanced in favor of Russia.

Back in 2010, when New START was first under consideration in the Senate, Kyl played a key role in extracting a pledge from the Obama administration to throw an extra $80 billion at the nuclear warhead complex in exchange for Republican support of the treaty. Even after that concession was made, Kyl continued to work tirelessly to build opposition to the treaty. If, in the end, he failed to block its Senate ratification, he did help steer billions in additional funding to the nuclear weapons complex.

In 2017, between stints in the Senate, Kyl worked as a lobbyist with the law firm Covington and Burling, where one of his clients was Northrop Grumman, the largest beneficiary of the Pentagon’s nuclear weapons spending binge. That company is the lead contractor on both the future B-21 nuclear bomber and Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). The Sentinel program drew widespread attention recently when it was revealed that, in just a few years, its estimated cost had jumped by an astonishing 81%, pushing the price for building those future missiles to more than $140 billion (with tens of billions more needed to operate them in their years of “service” to come).

That stunning cost spike for the Sentinel triggered a Pentagon review that could have led to a cancellation or major restructuring of the program. Instead, the Pentagon opted to stay the course despite the enormous price tag, asserting that the missile is “essential to U.S. national security and is the best option to meet the needs of our warfighters.”

Independent experts disagree. Former Secretary of Defense William Perry, for instance, has pointed out that such ICBMs are “some of the most dangerous weapons we have” because a president, warned of a possible nuclear attack by an enemy power, would have only minutes to decide whether to launch them, greatly increasing the risk of an accidental nuclear war triggered by a false alarm. Perry is hardly alone. In July 2024, 716 scientists, including 10 Nobel laureates and 23 members of the National Academies, called for the Sentinel to be canceled, describing the system as “expensive, dangerous, and unnecessary.”

Meanwhile, as vice chair of a congressionally mandated commission on the future of U.S. nuclear weapons policy, Kyl has been pushing a worst-case scenario regarding the current nuclear balance that could set the stage for producing even larger numbers of (Northrop Grumman-built) nuclear bombers, putting multiple warheads on (Northrop Grumman-built) Sentinel missiles, expanding the size of the nuclear warhead complex, and emplacing yet more tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. His is a call, in other words, to return to the days of the Cold War nuclear arms race at a moment when the lack of regular communication between Washington and Moscow can only increase the risk of a nuclear confrontation.

Kyl does seem to truly believe that building yet more nuclear weapons will indeed bolster this country’s security, and he’s hardly alone when it comes to Congress or, for that matter, the next Trump administration. Consider that a clear sign that reining in the nuclear arms race will involve not only making the construction of nuclear weapons far less lucrative, but also confronting the distinctly outmoded and unbearably dangerous arguments about their alleged strategic value.

In October 2023, when the Senate Armed Services Committee held a hearing on a report from the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission, it had an opportunity for a serious discussion of nuclear strategy and spending, and how best to prevent a nuclear war. Given the stakes for all of us should a nuclear war between the United States and Russia break out—up to an estimated 90 million of us dead within the first few days of such a conflict and up to five billion lives lost once radiation sickness and reduced food production from the resulting planetary “nuclear winter” kick in—you might have hoped for a wide-ranging debate on the implications of the commission’s proposals.

Unfortunately, much of the discussion during the hearing involved senators touting weapons systems or facilities producing them located in their states, with little or no analysis of what would best protect Americans and our allies. For example, Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.) stressed the importance of Raytheon’s SM-6 missile—produced in Arizona, of course—and commended the commission for proposing to spend more on that program. Sen. Jackie Rosen (R-Nev.) praised the role of the Nevada National Security Site, formerly known as the Nevada Test Site, for making sure such warheads were reliable and would explode as intended in a nuclear conflict. You undoubtedly won’t be shocked to learn that she then called for more funding to address what she described as “significant delays” in upgrading that Nevada facility. Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-Ala.) proudly pointed to the billions in military work being done in his state: “In Alabama we build submarines, ships, airplanes, missiles. You name it, we build it.” Sen. Eric Schmitt (R-Mo.) requested that witnesses confirm how absolutely essential the Kansas City Plant, which makes non-nuclear parts for nuclear weapons, remains for American security.

The next few years will be crucial in determining whether ever growing numbers of nuclear weapons remain entrenched in this country’s budgets and its global strategy for decades to come or whether common sense can carry the day and spark the reduction and eventual elimination of such instruments of mass devastation.

And so it went until Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) asked what the nuclear buildup recommended by the commission would cost. She suggested that, if past history is any guide, much of the funding proposed by the commission would be wasted: “I’m willing to spend what it takes to keep America safe, but I’m certainly not comfortable with a blank check for programs that already have a history of gross mismanagement.”

The answer from Kyl and his co-chair Marilyn Creedon was that the commission had not even bothered to estimate the costs of any of what it was suggesting and that its recommendations should be considered regardless of the price. This, of course, was good news for nuclear weapons contractors like Northrop Grumman, but bad news for taxpayers.

Nuclear hardliners frequently suggest that anyone advocating the reduction or elimination of nuclear arsenals is outrageously naive and thoroughly out of touch with the realities of great power politics. As it happens though, the truly naive ones are the nuclear hawks who insist on clinging to the dubious notion that vast (and still spreading) stores of nuclear weaponry can be kept around indefinitely without ever being used again, by accident or design.

There is another way. Even as Washington, Moscow, and Beijing continue the production of a new generation of nuclear weapons—such weaponry is also possessed by France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, and the United Kingdom—a growing number of nations have gone on record against any further nuclear arms race and in favor of eliminating such weapons altogether. In fact, the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons has now been ratified by 73 countries.

As Beatrice Fihn, former director of the Nobel-prize-winning International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, or ICAN, pointed out in a recent essay in The New York Times, there are numerous examples of how collective action has transformed “seemingly impossible situations.” She cited the impact of the antinuclear movement of the 1980s in reversing a superpower nuclear arms race and setting the stage for sharp reductions in the numbers of such weapons, as well as a successful international effort to bring the nuclear ban treaty into existence. She noted that a crucial first step in bringing the potentially catastrophic nuclear arms race under control would involve changing the way we talk about such weapons, especially debunking the myth that they are somehow “magical tools” that make us all more secure. She also emphasized the importance of driving home that this planet’s growing nuclear arsenals are evidence that all too many of those in power are acquiescing in a reckless strategy “based on threatening to commit global collective suicide.”

The next few years will be crucial in determining whether ever growing numbers of nuclear weapons remain entrenched in this country’s budgets and its global strategy for decades to come or whether common sense can carry the day and spark the reduction and eventual elimination of such instruments of mass devastation. A vigorous public debate on the risks of an accelerated nuclear arms race would be a necessary first step toward pulling the world back from the brink of Armageddon.

Sitting awkwardly with this phenomenon is a strange fact: According to Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority policy, “Advertisements that are intended to influence public policy are prohibited.”

The first thing commuters saw when stepping into the Metro station beneath the Pentagon in late August was a poster for RTX: the world’s second largest defense contractor, formerly known as Raytheon.

RTX made $30.3 billion in sales to the U.S. government last year, 45% of its total income. To advertise to its biggest customer, why not target government decision-makers in the places they visit most? Thus, the thousands of commuters entering the Pentagon station each day were greeted by more than 60 RTX advertisements plastered across the walls, floors, escalators, and fare gates such that it was physically impossible to pass through the station without seeing one.

This ad campaign wasn’t the company’s first rodeo, either. Ten years ago, RTX placed advertisements in the Pentagon station to promote a satellite control system. That same project is now seven years late and billions of dollars over-cost.

The catch is that, technically, advertisers aren’t supposed to be able to do this, as the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA, which operates the greater D.C. metro system) forbids advertisements that “are intended to influence public policy.” But government contractors, reliant on public policy for their survival, are nonetheless allowed to promote their brands and hawk their products to the officials responsible for deciding whether or not to buy from them. A closer investigation into their marketing tactics reveals how companies like RTX and Google have taken advantage of this lax enforcement to hijack D.C.’s public transportation system for their own gain. WMATA is not just allowing it, they’re profiting from it.

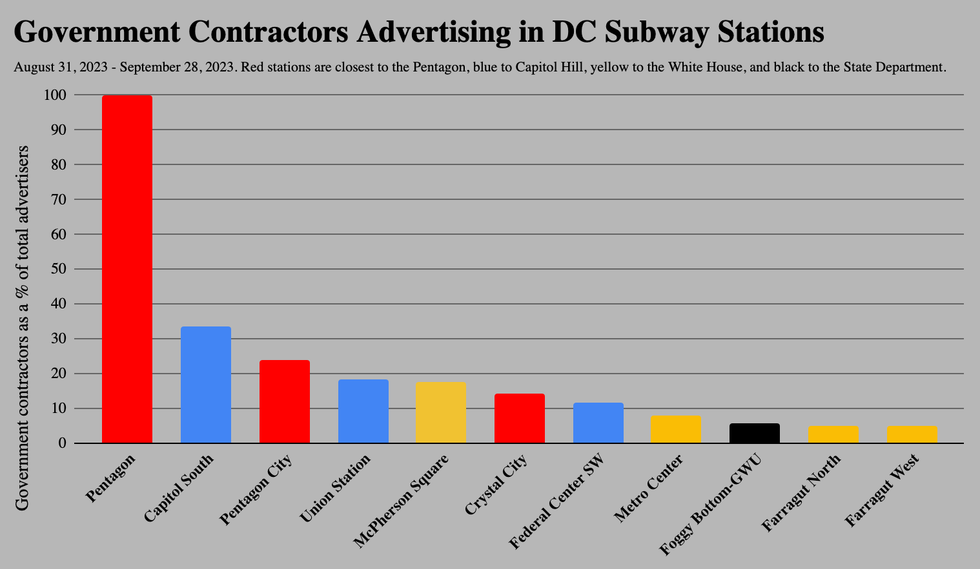

A graph shows the concentration of contractor advertisements at different D.C. Metro stations.

(Graphic: Brett Heinz/ Responsible Statecraft)

As the home to countless government agencies, Washington D.C.’s population is dense with people whose choices at work can affect the entire world. This has made the capital metro system a magnet for government contractors and other advertisers looking to shape policymakers’ activities.

Yet a systematic analysis of that advertising has proven difficult. WMATA does not make advertising data available to the public, and has yet to respond to multiple requests for the data. A similar request was denied by Outfront Media, the private marketing firm contracted by WMATA to handle transit ads.

So, I obtained what information I could the old-fashioned way—I rode the Metro, a lot. For five consecutive weeks, I visited 11 WMATA Metro stations and recorded the names of every advertiser. All were located within one mile of major policymaking institutions: Capitol Hill, the White House, the Pentagon, and the State Department.

Contractor advertising appears to be explicitly targeted at those with the greatest sway over government spending.

The survey recorded 75 different advertisers, excluding transit agencies. Fifteen received at least $5 million in financial awards from the federal government in fiscal year 2023. Four of those were universities and another was United Airlines, while the remaining 10 were government contractors. Altogether, these 10 contractors received approximately $83.1 billion from the federal government in FY2023.

Nine of the 10 advertising contractors count the Department of Defense (DOD) as their largest government customer: Boeing, CACI, General Dynamics, Google, IBM, KPMG, L3Harris, RTX, and SourceAmerica. Ads for McKesson, which does the vast majority of its government contracting for the Department of Veterans Affairs, were spotted only within the McPherson Square station—two blocks away from the VA headquarters.

While this survey was being conducted, Congress was preparing to meet in committee to negotiate the final version of this year’s National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which annually authorizes hundreds of billions of dollars that ultimately go to Pentagon contractors.

The data suggests that contractors are most focused on targeting the Pentagon and Capitol Hill. Contractors made up just 6% of all advertisers in Foggy Bottom-GWU, the only stop near the State Department. In the four stops around the White House, they averaged 9%. Among the three stops closest to Capitol Hill, this number rises to 21%. In the three stations closest to the Pentagon, an average of 46% of all advertisers were contractors.

The Pentagon station, less than 200 feet from the building’s entrance, was 100% occupied by government contractors. In Capitol South, similarly close to the offices of the House of Representatives, one-third of advertisers were contractors. The focus on these two institutions illustrates their importance in keeping contract money flowing: a slim majority of the massive DOD budget goes to contractors each year, and the institution plays a major role in shaping its own budget. The House, meanwhile, is where all budget bills begin. In short, contractor advertising appears to be explicitly targeted at those with the greatest sway over government spending.

An RTX ad is displayed at the Pentagon City Metro station on September 7, 2023.

(Photo: Brett Heinz/ Responsible Statecraft)

This pattern goes well beyond correlation. Many contractor ads are designed to steer a small number of commuters—agency acquisition officers and congressional appropriations staffers—towards specific government policies. To accomplish this, contractors often use niche language that only their customers would understand. One ad spotted in four stations near Capitol Hill and the Pentagon displayed the tail of a jet above two screens of text: “ENABLES BEYOND BLOCK 4 / ALL THREE F-35 VARIANTS” and “THE SMART DECISION.”

This bizarre message, which caught the attention of social media earlier this year, is promoting RTX’s F135 engine. Estimated to cost $26 million each, these upgrades can be added to “all three” versions of the F-35 jet, whose astronomical cost overruns have helped turn it into the most expensive weapons program in human history. Years ago, Lockheed Martin advertised this same plane in stations near the Pentagon with its own twist on a classic neoconservative slogan: “Peace through strength. Lots of strength.” Today, RTX promises that its add-on goes “beyond” the Block 4 upgrade for these planes (which itself is running $5.9 billion over previous cost estimates).

RTX has bragged to investors about the expensive contracts for its F135 engines, but it still faces competition from other contractors. The conflict between the two is set to be addressed by Congress during conference negotiations for this year’s NDAA. To help secure its new revenue stream, RTX placed ads promoting it in places where the people working on the NDAA will most likely see them, using language that only they would understand. RTX did not reply to a request for comment.

In the past, some firms have been transparent about their narrow audiences. Controversial contractor Palantir, which has handled many confidential contracts, once advertised in the Pentagon station with materials reading: “THOSE WITH A NEED TO KNOW, KNOW.

A Google ad is displayed at the Pentagon Metro station on September 28, 2023

(Photo: Brett Heinz/ Responsible Statecraft)

Outfront Media’s pitch to advertisers for the D.C. market area highlights its large audience of “political leaders, government employees, and corporate contractors.” To help reach them all, they offer a “Rail Station Domination” deal in 13 Metro stations to allow one advertiser to occupy much of the available space within, an opportunity, it says, to “transform commuters’ daily ride into a total ‘brand experience.’”

Outfront’s list of “Domination” stations includes brief descriptions of why they might be attractive to marketers: “U.S. Dept of Defense” for the Pentagon station, and “Capitol Hill” for Capitol South. Two other stations located near various regulatory agencies are listed simply as places to target “Government.” Contractors have long taken advantage of these deals, such as Lockheed Martin’s 2020 “domination” of Capitol South.

The Pentagon station, a prime target for reaching DOD staffers, was one of a kind. The Pentagon is the most expensive station to “dominate” according to Outfront Media data which I obtained, even though it has substantially fewer riders than some of the others. Advertising to the 665,786 commuters estimated to visit the Pentagon station in a four week period costs $198,000 (about 30 cents per commuter), before fees. Yet in Gallery Place-Chinatown, a station in downtown D.C. farther away from government buildings, it costs only $120,000 to reach more than three times as many people (5 cents per commuter).

The Pentagon is the most expensive station to “dominate” according to Outfront Media data which I obtained, even though it has substantially fewer riders than some of the others.

These pricing differences suggest that there is a unique value attached to commuters visiting the Pentagon. Another factor is the Pentagon’s unique layout, in which one advertiser can occupy the entire station for weeks on end, without any competition from others on digital screens. The five “domination” stations visited during this survey averaged 13.6 different advertisers over five weeks; the Pentagon featured only two. In the last week of August, every ad space inside the Pentagon station was occupied by RTX. For the entirety of September, it was Google.

Despite earning little from government contracts last year, Google ran a highly aggressive marketing campaign this September to attract more. Its domination of the Pentagon station featured over 60 ads about their commitment to partnering with the government on cybersecurity policy, one of which implied that the company was already acting in concert with the military: “The U.S. Department of Defense and Google are securing American digital defense systems.”

The company shied away from its nascent attempts to break into government contracting in 2018 after a controversial AI drone deal provoked employee protests. Google executives have more recently reversed course, increased their presence in northern Virginia, and unveiled “Google Public Sector” to fight for more defense contracts. Google Public Sector’s current managing director served as Chief Information Officer at the U.S. Navy until passing through the revolving door in March. The company’s success in winning part of a major software contract late last year suggests its efforts are already paying off.

At the same time that Google was dominating the Pentagon station, a second ad campaign downtown promoted the “Google Public Sector Forum,” where company executives spoke alongside current Pentagon officials. Reached for comment, the Defense Department emphasized that guidelines were in place to ensure that "DOD personnel participating in public engagements” acted in ways “appropriate and consistent with DOD and U.S. government policies.”

Google’s apparent dual advertising strategy reflects its diverse goals in reaching policymakers: accessing the deep pool of DOD contracting funds, lobbying Congress on a wide variety of legislation, and burnishing its image in the face of a historic anti-trust lawsuit filed against it by the Justice Department earlier this year.

Google and Outfront Media did not reply to a request for comment.

The Northrop Grumman MQ-4C Triton was developed under the Broad Area Maritime Surveillance (BAMS) program.

(Photo: U.S. Navy)

Sitting awkwardly with this phenomenon is a strange fact: According to WMATA policy, “Advertisements that are intended to influence public policy are prohibited.” Ads for specific military equipment are clearly meant to “influence” government acquisitions, which are “public policy” by definition. Nonetheless, Pentagon contractors appear to flaunt this rule with impunity.

While WMATA has declined a number of political ads before, it is still quite common for advertisers to push the limits of what qualifies as “intended to influence public policy.” No one pushes this boundary further than contractors. Prior to the ban’s creation in 2015, contractors openly acknowledged that they hoped to influence public policy. When Northrop Grumman advertised its Broad Area Maritime Surveillance (BAMS) system in the Pentagon station in 2007, a company spokesman said: “There is an ongoing campaign to win the BAMS contract… The Washington, D.C., area is where our customer base is, and we do want to build awareness for our products and services.”

WMATA declined to comment on questions related to the rule due to “pending litigation on this issue.” The American Civil Liberties Union has sued over this and other WMATA policies as violations of advertisers’ free speech rights, and the case was recently approved to move forward.

The seemingly arbitrary enforcement of WMATA’s ban on ads influencing public policy allows contractors to recycle government funds back into efforts to acquire more government funds.

Further complicating matters is a federal law banning contractors from spending public funds on “influencing or attempting to influence” government officials towards providing them with additional contracts. The rule does not seem to have dissuaded contractors, even those who derive the majority of their revenues from the federal government, from targeted advertising campaigns. (DOD spokesman Jeff Jurgensen emphasized that the agency complies with all relevant acquisitions regulations.)

Advertisers subsidize the D.C. Metro system by providing revenue that would otherwise need to come from either commuters or the government. WMATA hired Outfront Media to “maximize the revenue potential” of public transit assets, incentivizing the company to always go with the highest bidder. Still, WMATA’s budget for next year projects that Metro ads will only bring in $10.3 million, roughly 0.75% of the system’s total funding. This might save money on the front end, but advertisements encouraging billions in inefficient government spending could easily wind up costing taxpayers more over time, such that direct subsidies to replace WMATA’s revenues from contractor ads could ultimately save money.

The seemingly arbitrary enforcement of WMATA’s ban on ads influencing public policy allows contractors to recycle government funds back into efforts to acquire more government funds. This cycle encourages public officials to make choices based on power and reach, rather than cost-efficiency, fairness, or a rational defense strategy. As long as companies making money from policymakers’ decisions are allowed to advertise in the D.C. transit system, this corrupt process will continue to thrive.

“Huge CEO compensation,” William Hartung observes, “does nothing to advance the defense of the United States and everything to enrich a small number of individuals.”

Does anyone have a sweeter deal than military contractor CEOs?

The United States spent more last year on defense than the next 10 nations combined. A deal just brokered by the White House and House Republicans increases that amount even further—to $886 billion. Defense contractors will pocket about half of that.

Just eight years ago, the national defense community made do with over $300 billion less. But making do with “less” doesn’t come easy to corporate titans like Dave Calhoun, the CEO at Boeing, the nation’s second-largest defense contractor.

In 2021, the most recent year with complete stats, the nation’s top five weapons makers—Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, General Dynamics, and Northrop Grumman–grabbed over $116 billion in Pentagon contracts and paid their top executives $287 million.

In March, Boeing’s annual filings revealed that Calhoun had missed his CEO performance targets and would not be receiving a $7 million bonus. As a result, Calhoun had to be content with a mere $22.5 million in 2022—but to sweeten the deal, the Boeing board granted their CEO an extra stack of shares worth some $15 million at today’s value.

The Government Accountability Office may have had incidents just like that in mind when it urged the Pentagon to “comprehensively assess” its contract financing arrangements a few years ago.

This past April, the Department of Defense finally attempted to do it.

“In aggregate,” its report concludes, “the defense industry is financially healthy, and its financial health has improved over time.” But despite “increased profit and cash flow,” the DoD found, corporate contractors have chosen “to reduce the overall share of revenue” they spend on R&D.

Instead, they’re “significantly increasing the share of revenue paid to shareholders in cash dividends and share buybacks.” Those dividends and buybacks have jumped by an astounding 73%!

Contractor CEOs have been lining their pockets accordingly.

In 2021, the most recent year with complete stats, the nation’s top five weapons makers—Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, General Dynamics, and Northrop Grumman–grabbed over $116 billion in Pentagon contracts and paid their top executives $287 million, Pentagon-watcher William Hartung noted this past December.

Taxpayers subsidize these more-than-ample paychecks. Corporate giants like Boeing and Raytheon depend on government contracts for about half the dollars they rake in. For Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and Northrop Grumman, it’s at least 70%.

“Huge CEO compensation,” Hartung observes, “does nothing to advance the defense of the United States and everything to enrich a small number of individuals.”

Even before Biden and Republicans agreed to increase spending, the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) calculated the “militarized portion” of the federal budget at 62% of all discretionary spending.

We have precious little to show for this enormous expenditure.

“The post-9/11 ‘war on terror,’ for example, has cost more than $8 trillion and contributed to a horrific death toll of 4.5 million people in affected regions,” the IPS report notes. “Meanwhile, a U.S. military budget that outpaces Russia’s by more than 10 to one has failed to prevent or end the Russian war in Ukraine.”

So what can we do? The IPS analysts advocate reducing the national military budget by at least $100 billion and reinvesting the savings in social programs.

Progressive members of Congress, meanwhile, have also been pushing for a major change in contracting standards. Rep. Jan Schakowsky’s (D-Ill.) “Patriotic Corporations Act” would give companies with smaller pay gaps between their CEOs and workers a leg up in the bidding for federal defense contracts.

Or we could go the FDR route. In the year after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued an order limiting top corporate executive pay to $25,000 after taxes—a move Roosevelt said was needed “to correct gross inequities and to provide for greater equality in contributing to the war effort.”

By the war’s end, America’s wealthy were paying federal taxes on income over $200,000 at a 94% rate. That top rate hovered around 90% for the next two decades and helped give birth to the first mass middle class the world had ever seen.

Miracles can happen.