The Science Equivalent of Tearing Down the East Wing of the White House

The Trump administration’s decision to shut down the National Center for Atmospheric Research is the most traumatic item on a list of recent climate defeats.

It’s the end of the year, and so one should be compiling 10-best lists.

And I turned 65 last week, having spent almost my entire adult life in the climate fight, so it’s one of those moments when I wish I could look back with a certain amount of satisfaction.

But since I owe you honesty, not exuberance, just at the moment I can’t provide much celebration. I was hopeful this edition of the Crucial Years might be about a big victory—on Wednesday the board that controls New York City’s pension funds was considering whether or not to pull tens of billions from Blackrock because of the investment giant’s climate waffling, which would have been a massive display of courage. Sadly, the city Comptroller Brad Lander hadn’t gotten the measure on the agenda before the final meeting of his term, and he seems to have run out of time and political juice—the idea was tabled.

And so we’re left staring at a pile of recent defeats, at least in this country (which is an important qualification). I’ll try to end in a more hopeful place, but I fear you’re going to have to work through my angst with me for a few minutes.

The most traumatic item is the Trump administration’s decision to shut down the National Center for Atmospheric Research, born like me in 1960. It was a product of that era’s faith in science, a faith that paid off spectacularly. Take weather forecasting. As Nature reported Wednesday:

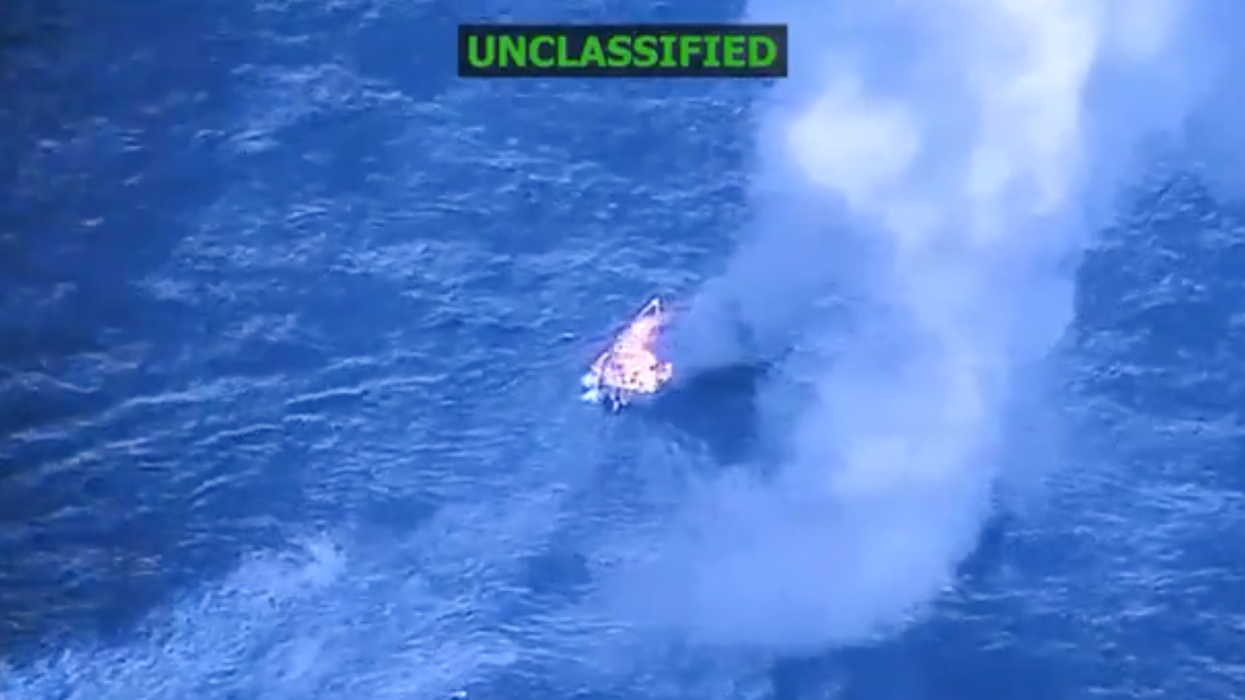

Work at NCAR played a key part in the rise of modern weather and climate forecasting. For instance, the lab pioneered the modern dropwindsonde, a weather instrument that can be released from an aircraft to measure conditions as it plummets through a storm. The technology reshaped the scientific understanding of hurricanes, says James Franklin, an atmospheric scientist and former branch chief of the hurricane specialist unit at the US National Hurricane Center in Miami, Florida.

But its most historically significant work has been in understanding the dimensions of the ongoing climate crisis. Nature again:

On the global scale, NCAR is known for its climate-modelling work, including the world-leading models that underpin international assessments such as those from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Hundreds of scientists pass through NCAR’s doors each year to collaborate with its researchers. More than 800 people are employed at NCAR, most of whom work at the centre’s three campuses in Boulder, including the iconic Mesa Lab that sits at the base of jagged mountain peaks and was designed by architect I. M. Pei.

There’s no question about why the administration is doing what it’s doing. Project 2025 enforcer Russell Vought explained it quite succinctly—NCAR must go because it is “one of the largest sources of climate alarmism in the country.” This is stupid—it’s like closing the fire department because it’s a source of “fire alarmism”—but it’s by now an entirely recognizable form of stupid. And it’s also sly: It’s like spraypainting over the surveillance cameras so you can rob the bank without anyone watching. But of course nothing changes with the underlying physics. Indeed, as the announcement came down, NCAR was closed for the day because:

the local electrical company planned to cut electricity preemptively to reduce wildfire risk as fierce winds were forecast around Boulder. In 2021, a wildfire ignited just kilometres from NCAR; fuelled by powerful winds, it ripped through suburban homes, killing two people. Many researchers say this is a new normal of increased fire risk in an era of climate change—a topic of study at NCAR.

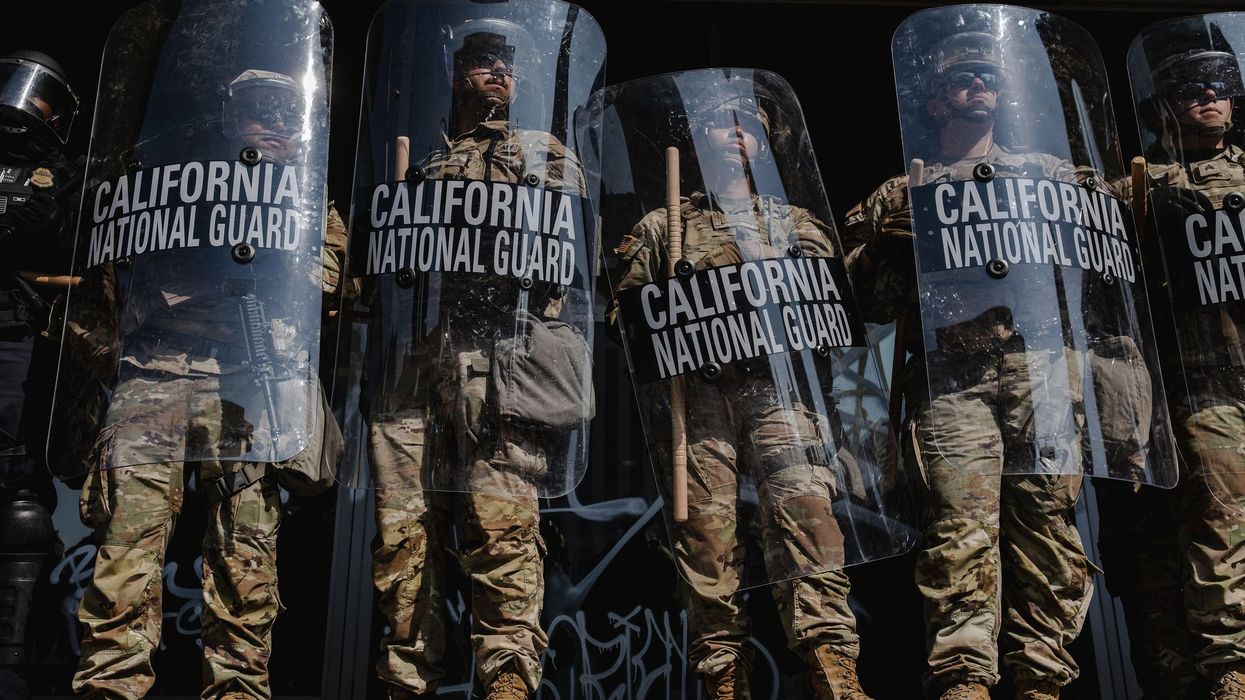

I am glad people are rallying to fight—there was an emergency press conference Thursday at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco, where many of the world’s Earth scientists are gathered. Third Act Colorado is working with Indivisible on a weekend rally. This is the scientific equivalent of tearing down the East Wing of the White House, and given the moment a lot more significant.

But I’m saddened to see how little our representatives in DC seem to really care, even the Democratic ones. Sixteen Democratic Senators voted Thursday to confirm President Donald Trump (and Elon Musk’s) nominee to head NASA, even though, as Brad Johnson pointed out in his Hill Heat newsletter, the administration is trying to slash science research at the agency in half. The new head, Jared Isaacman, is clearly on board. As he wrote this spring, “Take NASA out of the taxpayer funded climate science business and leave it for academia to determine.” But of course the administration is wrecking that too—they cut off the funding for the gold standard climate research program at Princeton on the grounds that it was “contributing to a phenomenon known as ‘climate anxiety,’ which has increased significantly among America’s youth.”

Too many Democratic leaders are feeling comfortable waving off climate concerns, because of a feeling that it might be a political problem for them. That was exemplified Thursday morning in the New York Times when center-right pundit Matt Yglesias issued a strident call for liberals to “support America’s oil and gas industry.” That he did it hours after that oil and gas industry won its fight to shutter climate research was probably coincidental, but the piece was a woebegone recycling of decades-old bad-faith arguments from a person who has insisted repeatedly that climate change is not an existential risk. Yglesias wants us to follow Obama-era "all of the above" energy policies even though they date from 15 years ago, when clean energy was more expensive than dirty, and long before we had the batteries that could make solar and wind fully useful. It’s no longer a good argument, but he has not changed his tune one iota—he keeps invoking Barack Obama, as if what was passable policy in 2008 still made sense.

The centerpiece of his argument is that we should support the gas industry because at least it produces less carbon than coal.

It is much cleaner than coal, consumption of which is still high and rising globally. Increased gas production, by displacing coal, has been the single largest driver of American emissions reductions over time. To the extent that foreign countries can be persuaded to rely on American gas exports rather than coal to fill the gaps left by the ongoing build-out of intermittent wind and solar that’s a climate win.

By now anyone following this debate knows that this is a mendacious point. That’s because the switch to gas has reduced American carbon emissions at the cost of increasing American methane emissions. Those who, like Yglesias, followed last year’s debate over pausing permitting for liquefied natural gas export terminals know that the crucial point was the science showing that in fact American LNG exports were worse than coal. The job is to get others to switch to solar, not coal—and that’s happening everywhere except the US, whose appetite for the stuff is apparently the thing still driving up global consumption even as demand drops in China and India.

Having written many many op-eds for the Times, I know that they fact-check things like the methane numbers; this should not have eluded them, but in fairness it’s eluded Democrats for decades, because gas has been such a convenient out for those unwilling to stand up to Big Oil. If I sound sore here, it’s because I’ve tried and failed to get this basic point of physics across; it’s just technical enough that senators often forget it, but ostensibly serious people like Yglesias should at least grapple with it.

All of this comes on the 10th anniversary of the Paris climate talks—and 10th anniversary of the Congress and (Democratic) president approving the resumption of US oil exports. I celebrated my 55th in Paris, and I remember being hunched over a laptop at a cafe writing what I think may have been the only op-ed opposing that resumption. As I said at the time:

It’s especially galling that Senate leaders—Republicans and Democrats—are apparently talking about trading this gift to Exxon and its ilk for tax breaks for wind and solar providers. It’s hard to imagine a better illustration of politicians who simply don’t understand the physics of climate change. We don’t need more of all kinds of energy—we need more of the clean stuff and way, way less of the dirty. Physics doesn’t do backroom deals.

And indeed the senators who said it was no big deal were wrong. America is, as Tony Dutzik pointed out this week, now the biggest oil exporter on Earth. He lays out the case nicely:

“There is currently little if any incentive for US oil producers to export crude oil even if the ban is lifted,” wrote Michael Levi of the Council on Foreign Relations, for example, in December 2015.

A decade later, those breezy assessments have proven to be wildly off-base. “The United States produces more crude oil than any country, ever,” reads a 2024 headline from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), one of the agencies that got it wrong. Not only did lifting the crude export ban lead to a surge in oil production, but it also dramatically reshaped the global energy system, US politics, and greenhouse gas emissions.

So, anyway, feeling a little sad. But I do think this is a low point, because I think around the rest of the world, where Trump (and pundits like Yglesias) have marginally less sway, things are continuing to break the right way. In fact, earlier today the premier journal Science picked its scientific “Breakthrough of the Year” and it turned out to be not some fascinating if arcane new discovery, but instead the prosaic but powerful spread of renewable energy around the planet:

This year, renewables surpassed coal as a source of electricity worldwide, and solar and wind energy grew fast enough to cover the entire increase in global electricity use from January to June, according to energy think tank Ember. In September, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared at the United Nations that his country will cut its carbon emissions by as much as 10% in a decade, not by using less energy, but by doubling down on wind and solar. And solar panel imports in Africa and South Asia have soared, as people in those regions realized rooftop solar can cheaply power lights, cellphones, and fans. To many, the continued growth of renewables now seems unstoppable—a prospect that has led Science to name the renewable energy surge its 2025 Breakthrough of the Year.

The tsunami of tech spilling from China’s factories has changed the country’s energy landscape—and its physical one, too. For decades China’s development was synonymous with coal, which produced choking air pollution and massive carbon emissions, still greater than those of all other developed nations combined. Now, solar panels carpet deserts and the high, sunstruck plateau of Tibet, and wind turbines up to 300 meters tall guard coastlines and hilltops (see photo essay, below). China’s solar power generation grew more than 20-fold over the past decade, and its solar and wind farms now have enough capacity to power the entire United States.

China’s burgeoning exports of green tech are transforming the rest of the world, too. Europe is a longtime customer, but countries in the Global South are also rushing to buy China’s solar panels, batteries, and wind turbines, spurred by market forces and a desire for energy independence. In Pakistan, for example, imports of Chinese solar panels grew fivefold from 2022 to ’24 as the Ukraine war pushed up natural gas prices and the cost of grid power. “For people who were asking, ‘How am I going to keep the lights on in my home,’ it was a very obvious choice,” says Lauri Myllyvirta, an analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. In South Africa, old and unreliable coal plants drove a similar dynamic. Ethiopia has embraced solar and wind amid worries that hydropower, the country’s mainstay, will decline as droughts become more frequent.

That’s the fight as we head into 2026. Trump and Big Oil have had the run of things this year, but their idiocy is pushing up against limits: Among other things, it turns out that permitting every data center imaginable while cutting off the supply of cheap sun and wind is sending energy prices through the roof, which may be a real issue as midterms loom.

I’m not retiring—I’m here for the fight, and you too I hope.