SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

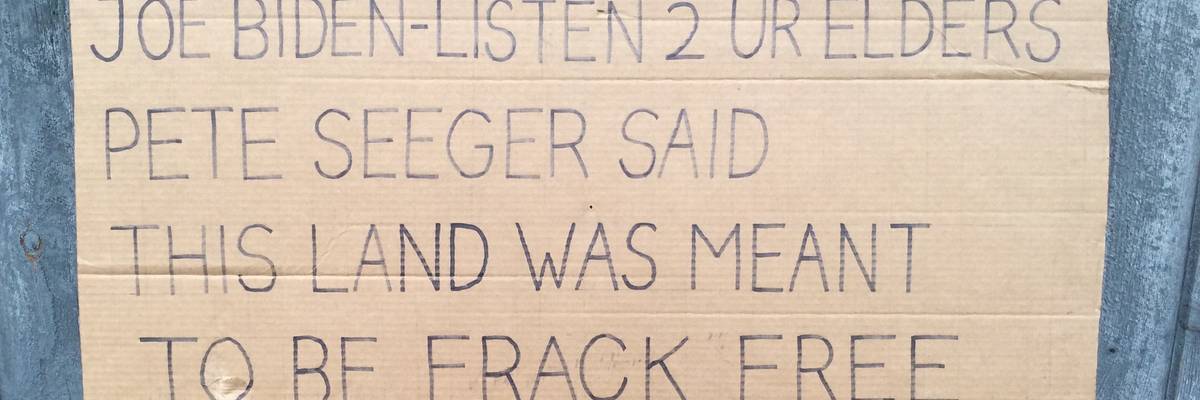

A protest sign is displayed calling on Joe Biden to follow Pete Seeger’s wishes that this land be frack free.

The Dirty Debt Deal did not make MVP a Done Deal; as Seeger sang, “We can never give up hope.”

Last week’s

climate march and actions, coupled with the annual Farm Aid concert, brought back fond memories of Pete Seeger. Ten years ago, at age 94, Pete dragged his long, lean, tired body 130 miles upstream from his Beacon, New York, home to the 2013 Farm Aid concert in Saratoga. His sole purpose for going was to sing an anti-fracking verse he had just written to Woody Guthrie’s “This Land.”

Pete had long been a part of New York’s powerful grassroots anti-fracking movement. He would show up every January, banjo in hand, at Albany’s Empire State Plaza, where a raucous crowd always greeted politicians and big wigs on their way to hear Andrew Cuomo deliver his annual State of the State address. The Saratoga Farm Aid concert was Pete’s last big hurrah. Two months later, he joined Arlo and family, as he always did, at Carnegie Hall. But he needed two canes to walk onstage, and he had to sit throughout. His mind was still sharp, but the rest of his body was giving out. Two months later, it did.

But that September night in Saratoga was magical. It almost didn’t happen. It was touch and go whether Pete’s daughter Tinya, her parents’ caregiver and gatekeeper, would allow it. She was told that if she didn’t think he was up to it, she needn’t say more. But if she thought he was, it would definitely be great for the anti-fracking movement and likely for him, personally, as well. And it certainly was, on both counts.

If Pete was still alive and able, I think he would have also made his way down to Virginia and West Virginia to witness and speak out against the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP).

No one in the audience knew Pete would be there, and when he walked out on stage he got the warmest of welcomes. He could no longer really sing himself, but he relied on his specialty—getting the audience to sing. Pete’s hearing was pretty well shot, too, and things got a little chaotic when he and Neil (who was thoroughly enjoying the moment) sang different verses at the same time. Then Pete raised his hand, hushed the crowd, and said “I’ve got a verse you’ve never heard before.”

New York is my home

New York is your home

From the upstate mountains

Down to the ocean foam

Then came the part about diversity, which Pete championed his whole life.

With all kinds of people

Yes, we’re polychrome

And then the kicker—

New York was meant

To be frack-free

The crowd erupted. Rolling Stone called it the high point of an always tremendous Farm Aid concert.

The following summer Jackson Browne came to Albany. Jackson was (and is) against fracking, and he was asked to pay tribute to Pete by singing “This Land” with Pete’s verse. Word came back that he wouldn’t sing “This Land,” but he would add Pete’s verse to “I Am A Patriot,” which caused some head scratching. How was he going to pull that off? Turns out, masterfully. And in hindsight it was no doubt very thoughtful on Jackson’s part, a nod to all that Pete had to put up with back in the Joe McCarthy era. Jackson introduced the verse by saying, “Pete was one of the greatest American songwriters, certainly one of the greatest Americans ever.” For sure.

A few months later New York banned fracking.

Pete was a world famous guy who could be seen holding a sign on his hometown street corner during a Saturday morning protest with neighbors. He sang about war and peace, but he also said something like, “How can you save the world if you can’t even clean up the river in your own backyard?” And so he built a boat called the Clearwater and founded an organization with the same name to do just that—clean up the Hudson River.

If Pete was still alive and able, he certainly would have been at the climate march in NYC. I think he would have also made his way down to Virginia and West Virginia to witness and speak out against the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP).

A few weeks ago, Denali Sai Nalamalapu, a frontline organizer trying to stop MVP, wrote a very good article asking why so many people would be going to the NYC climate march when so few were going to Appalachia to protest MVP. The main reason may be that most people erroneously believe MVP is a lost cause, which isn’t surprising because mainstream media, by and large, has said it is. But the Dirty Debt Deal does not mean that MVP is a done deal.

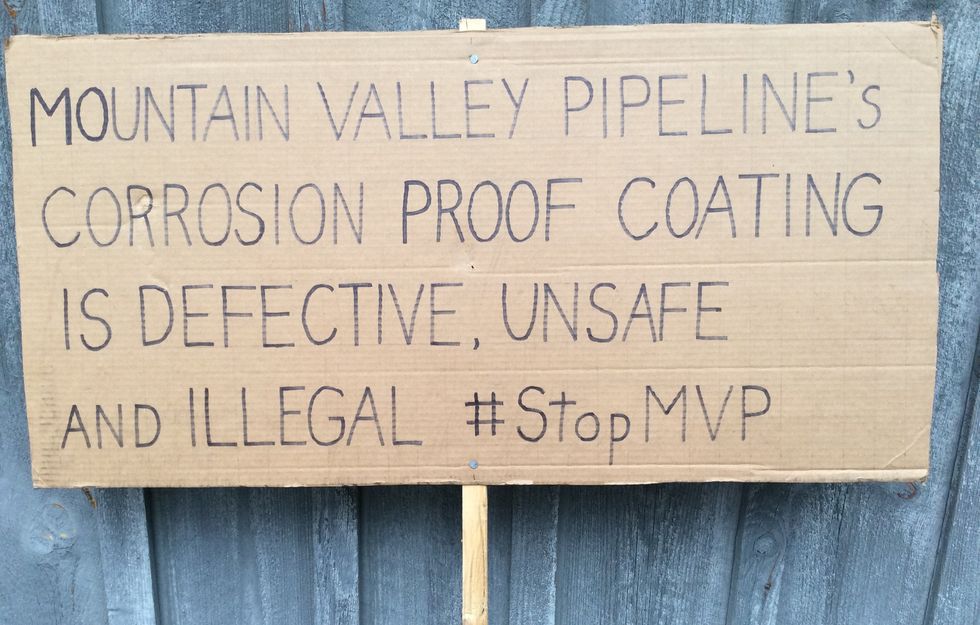

Even MVP’s own lawyer said that the debt deal does not prevent bringing legal claims as long as they are outside of the permitting process. MVP is violating a 52-year-old law that has nothing to do with the permitting process. It says that ALL pipe MUST have a corrosion-proof external coating that is “sufficiently ductile to resist cracking.” The reason is simple and obvious. Cracked corrosion-proof coating is an oxymoron.

MVP’s coating is no longer ductile (meaning flexible) enough to resist cracking because it has sat out in the sun for over six years, 12 times longer than the coating manufacturer recommends. Even a senior MVP vice president, testifying in court 68 MONTHS AGO, during an eminent domain hearing, said that they needed to quickly get the pipe in the ground so that the sun wouldn’t deteriorate the coating (p 134). If you had to take a really important medicine to prevent a really bad health problem, would you take one that expired six years ago? Adequate corrosion-proofing is critical for gas pipelines. We recently saw how inferior materials can lead to disaster. People have died due to explosions caused by corroded pipe. MVP is a particularly dangerous pipeline. It’s huge (42-inch diameter). It will be able to operate under extremely high pressure (1,480 pounds per square inch). And it is being built up and down very steep terrain that is prone to landslides.

Unless and until MVP pipe coating is thoroughly and independently tested in a transparent manner, test results of Keystone XL (KXL) pipe coating, which also sat out in the sun for years, should be what guides decision making. Every sample of KXL coating cracked when subjected to a flexibility test. They all failed the “sufficiently ductile to resist cracking” legal requirement. And no less than a KXL pipeline manager said that the coating can’t be fixed in the field. He said it required shipping the pipe back to the factory where it could be properly stripped, cleaned, and recoated.

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) recognizes that MVP has coating (and other) problems. It sent Equitrans, the company building MVP, a Notice of Proposed Safety Order ( NOPSO) on August 11. NOPSOs are rare. Only two have been issued this year and, on average, only 2.7 have been issued yearly for the past decade.

The NOPSO said that MVP (Equitrans) could request an informal consultation with PHMSA to discuss the proposed safety order. If that consultation results in an agreement between the parties on a plan and schedule to address each safety risk identified, then PHMSA would issue a consent order outlining the terms of the agreement. If an agreement is not reached, then MVP can request a formal hearing. Following the hearing, if the associate administrator finds MVP to have a condition that poses a pipeline integrity risk to the public, property, or the environment, the associate administrator may issue a final safety order. PHMSA’s associate administrator for pipeline safety is Alan K. Mayberry, the senior federal career official for pipeline safety in the United States. The day after the NOPSO was sent, MVP asked for a consultation and reserved the right to ask for a hearing. The NOPSO said that all material MVP submits in response to the enforcement action would be subject to being made publicly available. So far, almost seven weeks since the NOPSO was sent, there has been no further information released to the public. One can only imagine what kind of pressure is being applied to career public servants at PHMSA by higher up PHMSA political appointees, Equitrans, and politicians like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.).

Equitrans, by the way, was responsible for last year’s biggest U.S. climate disaster, a methane leak that it was unable to stop for 13 days. The leak was caused by… corrosion.

So let’s hope that Mr. Mayberry, eastern regional director Robert Burrough, and others at PHMSA are real serious about safety, and that some lawyer or environmental organization is ready to file suit concerning the “sufficiently ductile to resist cracking” rule, if need be.

What comes to mind when thinking about Joe Manchin and MVP is that old Pete Seeger song:

Well, I’m not going to point any moral,

I’ll leave that for yourself

Maybe you’re still walking, you’re still talking

You’d like to keep your health.

But every time I read the papers

That old feeling comes on;

We’re, waist deep in the Big Muddy

And the big fool says to push on.

But I also think of one of his most inspiring songs: “God’s Counting On Me, God’s Counting On You:”

When there’s big problems to be solved

Let’s get everyone involved

and

When we work with younger folks

We can never give up hope

President Joe Biden needs to think more about these younger folks’ future when he considers approving new fossil fuel infrastructure, and he sure shouldn’t let any pipelines get built that might blow up in their backyard or next to their school.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Last week’s

climate march and actions, coupled with the annual Farm Aid concert, brought back fond memories of Pete Seeger. Ten years ago, at age 94, Pete dragged his long, lean, tired body 130 miles upstream from his Beacon, New York, home to the 2013 Farm Aid concert in Saratoga. His sole purpose for going was to sing an anti-fracking verse he had just written to Woody Guthrie’s “This Land.”

Pete had long been a part of New York’s powerful grassroots anti-fracking movement. He would show up every January, banjo in hand, at Albany’s Empire State Plaza, where a raucous crowd always greeted politicians and big wigs on their way to hear Andrew Cuomo deliver his annual State of the State address. The Saratoga Farm Aid concert was Pete’s last big hurrah. Two months later, he joined Arlo and family, as he always did, at Carnegie Hall. But he needed two canes to walk onstage, and he had to sit throughout. His mind was still sharp, but the rest of his body was giving out. Two months later, it did.

But that September night in Saratoga was magical. It almost didn’t happen. It was touch and go whether Pete’s daughter Tinya, her parents’ caregiver and gatekeeper, would allow it. She was told that if she didn’t think he was up to it, she needn’t say more. But if she thought he was, it would definitely be great for the anti-fracking movement and likely for him, personally, as well. And it certainly was, on both counts.

If Pete was still alive and able, I think he would have also made his way down to Virginia and West Virginia to witness and speak out against the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP).

No one in the audience knew Pete would be there, and when he walked out on stage he got the warmest of welcomes. He could no longer really sing himself, but he relied on his specialty—getting the audience to sing. Pete’s hearing was pretty well shot, too, and things got a little chaotic when he and Neil (who was thoroughly enjoying the moment) sang different verses at the same time. Then Pete raised his hand, hushed the crowd, and said “I’ve got a verse you’ve never heard before.”

New York is my home

New York is your home

From the upstate mountains

Down to the ocean foam

Then came the part about diversity, which Pete championed his whole life.

With all kinds of people

Yes, we’re polychrome

And then the kicker—

New York was meant

To be frack-free

The crowd erupted. Rolling Stone called it the high point of an always tremendous Farm Aid concert.

The following summer Jackson Browne came to Albany. Jackson was (and is) against fracking, and he was asked to pay tribute to Pete by singing “This Land” with Pete’s verse. Word came back that he wouldn’t sing “This Land,” but he would add Pete’s verse to “I Am A Patriot,” which caused some head scratching. How was he going to pull that off? Turns out, masterfully. And in hindsight it was no doubt very thoughtful on Jackson’s part, a nod to all that Pete had to put up with back in the Joe McCarthy era. Jackson introduced the verse by saying, “Pete was one of the greatest American songwriters, certainly one of the greatest Americans ever.” For sure.

A few months later New York banned fracking.

Pete was a world famous guy who could be seen holding a sign on his hometown street corner during a Saturday morning protest with neighbors. He sang about war and peace, but he also said something like, “How can you save the world if you can’t even clean up the river in your own backyard?” And so he built a boat called the Clearwater and founded an organization with the same name to do just that—clean up the Hudson River.

If Pete was still alive and able, he certainly would have been at the climate march in NYC. I think he would have also made his way down to Virginia and West Virginia to witness and speak out against the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP).

A few weeks ago, Denali Sai Nalamalapu, a frontline organizer trying to stop MVP, wrote a very good article asking why so many people would be going to the NYC climate march when so few were going to Appalachia to protest MVP. The main reason may be that most people erroneously believe MVP is a lost cause, which isn’t surprising because mainstream media, by and large, has said it is. But the Dirty Debt Deal does not mean that MVP is a done deal.

Even MVP’s own lawyer said that the debt deal does not prevent bringing legal claims as long as they are outside of the permitting process. MVP is violating a 52-year-old law that has nothing to do with the permitting process. It says that ALL pipe MUST have a corrosion-proof external coating that is “sufficiently ductile to resist cracking.” The reason is simple and obvious. Cracked corrosion-proof coating is an oxymoron.

MVP’s coating is no longer ductile (meaning flexible) enough to resist cracking because it has sat out in the sun for over six years, 12 times longer than the coating manufacturer recommends. Even a senior MVP vice president, testifying in court 68 MONTHS AGO, during an eminent domain hearing, said that they needed to quickly get the pipe in the ground so that the sun wouldn’t deteriorate the coating (p 134). If you had to take a really important medicine to prevent a really bad health problem, would you take one that expired six years ago? Adequate corrosion-proofing is critical for gas pipelines. We recently saw how inferior materials can lead to disaster. People have died due to explosions caused by corroded pipe. MVP is a particularly dangerous pipeline. It’s huge (42-inch diameter). It will be able to operate under extremely high pressure (1,480 pounds per square inch). And it is being built up and down very steep terrain that is prone to landslides.

Unless and until MVP pipe coating is thoroughly and independently tested in a transparent manner, test results of Keystone XL (KXL) pipe coating, which also sat out in the sun for years, should be what guides decision making. Every sample of KXL coating cracked when subjected to a flexibility test. They all failed the “sufficiently ductile to resist cracking” legal requirement. And no less than a KXL pipeline manager said that the coating can’t be fixed in the field. He said it required shipping the pipe back to the factory where it could be properly stripped, cleaned, and recoated.

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) recognizes that MVP has coating (and other) problems. It sent Equitrans, the company building MVP, a Notice of Proposed Safety Order ( NOPSO) on August 11. NOPSOs are rare. Only two have been issued this year and, on average, only 2.7 have been issued yearly for the past decade.

The NOPSO said that MVP (Equitrans) could request an informal consultation with PHMSA to discuss the proposed safety order. If that consultation results in an agreement between the parties on a plan and schedule to address each safety risk identified, then PHMSA would issue a consent order outlining the terms of the agreement. If an agreement is not reached, then MVP can request a formal hearing. Following the hearing, if the associate administrator finds MVP to have a condition that poses a pipeline integrity risk to the public, property, or the environment, the associate administrator may issue a final safety order. PHMSA’s associate administrator for pipeline safety is Alan K. Mayberry, the senior federal career official for pipeline safety in the United States. The day after the NOPSO was sent, MVP asked for a consultation and reserved the right to ask for a hearing. The NOPSO said that all material MVP submits in response to the enforcement action would be subject to being made publicly available. So far, almost seven weeks since the NOPSO was sent, there has been no further information released to the public. One can only imagine what kind of pressure is being applied to career public servants at PHMSA by higher up PHMSA political appointees, Equitrans, and politicians like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.).

Equitrans, by the way, was responsible for last year’s biggest U.S. climate disaster, a methane leak that it was unable to stop for 13 days. The leak was caused by… corrosion.

So let’s hope that Mr. Mayberry, eastern regional director Robert Burrough, and others at PHMSA are real serious about safety, and that some lawyer or environmental organization is ready to file suit concerning the “sufficiently ductile to resist cracking” rule, if need be.

What comes to mind when thinking about Joe Manchin and MVP is that old Pete Seeger song:

Well, I’m not going to point any moral,

I’ll leave that for yourself

Maybe you’re still walking, you’re still talking

You’d like to keep your health.

But every time I read the papers

That old feeling comes on;

We’re, waist deep in the Big Muddy

And the big fool says to push on.

But I also think of one of his most inspiring songs: “God’s Counting On Me, God’s Counting On You:”

When there’s big problems to be solved

Let’s get everyone involved

and

When we work with younger folks

We can never give up hope

President Joe Biden needs to think more about these younger folks’ future when he considers approving new fossil fuel infrastructure, and he sure shouldn’t let any pipelines get built that might blow up in their backyard or next to their school.

Last week’s

climate march and actions, coupled with the annual Farm Aid concert, brought back fond memories of Pete Seeger. Ten years ago, at age 94, Pete dragged his long, lean, tired body 130 miles upstream from his Beacon, New York, home to the 2013 Farm Aid concert in Saratoga. His sole purpose for going was to sing an anti-fracking verse he had just written to Woody Guthrie’s “This Land.”

Pete had long been a part of New York’s powerful grassroots anti-fracking movement. He would show up every January, banjo in hand, at Albany’s Empire State Plaza, where a raucous crowd always greeted politicians and big wigs on their way to hear Andrew Cuomo deliver his annual State of the State address. The Saratoga Farm Aid concert was Pete’s last big hurrah. Two months later, he joined Arlo and family, as he always did, at Carnegie Hall. But he needed two canes to walk onstage, and he had to sit throughout. His mind was still sharp, but the rest of his body was giving out. Two months later, it did.

But that September night in Saratoga was magical. It almost didn’t happen. It was touch and go whether Pete’s daughter Tinya, her parents’ caregiver and gatekeeper, would allow it. She was told that if she didn’t think he was up to it, she needn’t say more. But if she thought he was, it would definitely be great for the anti-fracking movement and likely for him, personally, as well. And it certainly was, on both counts.

If Pete was still alive and able, I think he would have also made his way down to Virginia and West Virginia to witness and speak out against the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP).

No one in the audience knew Pete would be there, and when he walked out on stage he got the warmest of welcomes. He could no longer really sing himself, but he relied on his specialty—getting the audience to sing. Pete’s hearing was pretty well shot, too, and things got a little chaotic when he and Neil (who was thoroughly enjoying the moment) sang different verses at the same time. Then Pete raised his hand, hushed the crowd, and said “I’ve got a verse you’ve never heard before.”

New York is my home

New York is your home

From the upstate mountains

Down to the ocean foam

Then came the part about diversity, which Pete championed his whole life.

With all kinds of people

Yes, we’re polychrome

And then the kicker—

New York was meant

To be frack-free

The crowd erupted. Rolling Stone called it the high point of an always tremendous Farm Aid concert.

The following summer Jackson Browne came to Albany. Jackson was (and is) against fracking, and he was asked to pay tribute to Pete by singing “This Land” with Pete’s verse. Word came back that he wouldn’t sing “This Land,” but he would add Pete’s verse to “I Am A Patriot,” which caused some head scratching. How was he going to pull that off? Turns out, masterfully. And in hindsight it was no doubt very thoughtful on Jackson’s part, a nod to all that Pete had to put up with back in the Joe McCarthy era. Jackson introduced the verse by saying, “Pete was one of the greatest American songwriters, certainly one of the greatest Americans ever.” For sure.

A few months later New York banned fracking.

Pete was a world famous guy who could be seen holding a sign on his hometown street corner during a Saturday morning protest with neighbors. He sang about war and peace, but he also said something like, “How can you save the world if you can’t even clean up the river in your own backyard?” And so he built a boat called the Clearwater and founded an organization with the same name to do just that—clean up the Hudson River.

If Pete was still alive and able, he certainly would have been at the climate march in NYC. I think he would have also made his way down to Virginia and West Virginia to witness and speak out against the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP).

A few weeks ago, Denali Sai Nalamalapu, a frontline organizer trying to stop MVP, wrote a very good article asking why so many people would be going to the NYC climate march when so few were going to Appalachia to protest MVP. The main reason may be that most people erroneously believe MVP is a lost cause, which isn’t surprising because mainstream media, by and large, has said it is. But the Dirty Debt Deal does not mean that MVP is a done deal.

Even MVP’s own lawyer said that the debt deal does not prevent bringing legal claims as long as they are outside of the permitting process. MVP is violating a 52-year-old law that has nothing to do with the permitting process. It says that ALL pipe MUST have a corrosion-proof external coating that is “sufficiently ductile to resist cracking.” The reason is simple and obvious. Cracked corrosion-proof coating is an oxymoron.

MVP’s coating is no longer ductile (meaning flexible) enough to resist cracking because it has sat out in the sun for over six years, 12 times longer than the coating manufacturer recommends. Even a senior MVP vice president, testifying in court 68 MONTHS AGO, during an eminent domain hearing, said that they needed to quickly get the pipe in the ground so that the sun wouldn’t deteriorate the coating (p 134). If you had to take a really important medicine to prevent a really bad health problem, would you take one that expired six years ago? Adequate corrosion-proofing is critical for gas pipelines. We recently saw how inferior materials can lead to disaster. People have died due to explosions caused by corroded pipe. MVP is a particularly dangerous pipeline. It’s huge (42-inch diameter). It will be able to operate under extremely high pressure (1,480 pounds per square inch). And it is being built up and down very steep terrain that is prone to landslides.

Unless and until MVP pipe coating is thoroughly and independently tested in a transparent manner, test results of Keystone XL (KXL) pipe coating, which also sat out in the sun for years, should be what guides decision making. Every sample of KXL coating cracked when subjected to a flexibility test. They all failed the “sufficiently ductile to resist cracking” legal requirement. And no less than a KXL pipeline manager said that the coating can’t be fixed in the field. He said it required shipping the pipe back to the factory where it could be properly stripped, cleaned, and recoated.

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) recognizes that MVP has coating (and other) problems. It sent Equitrans, the company building MVP, a Notice of Proposed Safety Order ( NOPSO) on August 11. NOPSOs are rare. Only two have been issued this year and, on average, only 2.7 have been issued yearly for the past decade.

The NOPSO said that MVP (Equitrans) could request an informal consultation with PHMSA to discuss the proposed safety order. If that consultation results in an agreement between the parties on a plan and schedule to address each safety risk identified, then PHMSA would issue a consent order outlining the terms of the agreement. If an agreement is not reached, then MVP can request a formal hearing. Following the hearing, if the associate administrator finds MVP to have a condition that poses a pipeline integrity risk to the public, property, or the environment, the associate administrator may issue a final safety order. PHMSA’s associate administrator for pipeline safety is Alan K. Mayberry, the senior federal career official for pipeline safety in the United States. The day after the NOPSO was sent, MVP asked for a consultation and reserved the right to ask for a hearing. The NOPSO said that all material MVP submits in response to the enforcement action would be subject to being made publicly available. So far, almost seven weeks since the NOPSO was sent, there has been no further information released to the public. One can only imagine what kind of pressure is being applied to career public servants at PHMSA by higher up PHMSA political appointees, Equitrans, and politicians like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.).

Equitrans, by the way, was responsible for last year’s biggest U.S. climate disaster, a methane leak that it was unable to stop for 13 days. The leak was caused by… corrosion.

So let’s hope that Mr. Mayberry, eastern regional director Robert Burrough, and others at PHMSA are real serious about safety, and that some lawyer or environmental organization is ready to file suit concerning the “sufficiently ductile to resist cracking” rule, if need be.

What comes to mind when thinking about Joe Manchin and MVP is that old Pete Seeger song:

Well, I’m not going to point any moral,

I’ll leave that for yourself

Maybe you’re still walking, you’re still talking

You’d like to keep your health.

But every time I read the papers

That old feeling comes on;

We’re, waist deep in the Big Muddy

And the big fool says to push on.

But I also think of one of his most inspiring songs: “God’s Counting On Me, God’s Counting On You:”

When there’s big problems to be solved

Let’s get everyone involved

and

When we work with younger folks

We can never give up hope

President Joe Biden needs to think more about these younger folks’ future when he considers approving new fossil fuel infrastructure, and he sure shouldn’t let any pipelines get built that might blow up in their backyard or next to their school.