SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

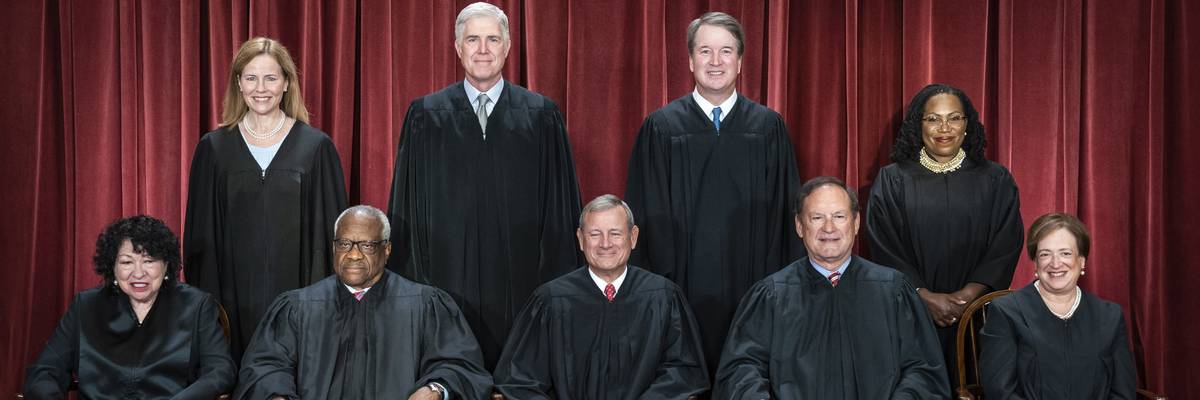

Members of the Supreme Court sit for a group photo following the recent addition of Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, at the Supreme Court building on Capitol Hill on Friday, Oct 07, 2022 in Washington, DC. Bottom row, from left, Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan. Top row, from left, Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

Is the Court under Chief Justice Roberts more conservative than its predecessors?

Rulings issued by the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) increasingly appear to be ideologically driven, often splitting along a clear conservative-liberal divide—whether 5–4 when there were five conservative justices, or 6–3 following the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her replacement by the more conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett, appointed by President Trump. The relatively recent Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health ruling in June 2022, where the conservative majority overturned Roe v. Wade by a 6-3 split, underscores this point.

This pattern of partisan alignment contributes to a broader fear, especially in the wake of President Trump’s reelection, that America’s bulwarks of democracy are buckling. From attacks on civil rights, universities, and the press, to a Justice Department willing to arrest sitting judges, Trump’s actions seem designed to destabilize core institutions. At the same time, his roughshod approach to “justice” is almost cynically expected to end up in the courts—particularly at SCOTUS—where many assume the ruling will go his way. The common narrative in progressive circles warns that the Court, stacked with Trump appointees, will support him in any unconstitutional attempt to hold power. While we have no quibble about their assessment that President Trump is a bad hombre who will do his best to do his worst, we are not convinced that SCOTUS will ever do his bidding. And though three of its justices were appointed by Trump and others often align ideologically, SCOTUS has shown itself, at times, to resist political pressure. It may still serve as a vital check on executive overreach. Whether it can fulfill that role is a question worth answering not just with alarm, but with close attention to facts and patterns. But first, some context and examples.

Recall that SCOTUS dismissed Texas v. Pennsylvania in December 2020 because Texas lacked standing in how Pennsylvania (but also other states) conducts its elections. The unsigned order stated: “Texas has not demonstrated a judicially cognizable interest in the manner in which another State conducts its elections.” No Justice supported Texas’s request for relief, though Justices Alito and Thomas would have allowed the complaint to be filed. SCOTUS rejected or refused to hear all other major legal challenges by Trump or his allies to the 2020 elections. This is despite the 6-3 conservative majority in the Court.

Similarly, there are other examples too, and not just those related to elections, that don’t fit the narrative that the three new Justices nominated by Trump will upend all the civil rights, due process, or other liberties we enjoy. Take Bostock v. Clayton County (2020), a landmark civil rights case where, in a 6-3 ruling, the Court ruled the Civil Rights Act protects employees against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. The majority opinion was written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, and while dissenting justices Alito, Thomas, and Kavanaugh are also conservatives, Justice Kavanaugh wrote a separate dissent arguing it should be Congress and not the courts that should add gender and sexual orientation to Title VII. He stated,

“Millions of gay and lesbian Americans have worked hard for many decades to achieve equal treatment in fact and law ... They have advanced powerful policy arguments and can take pride in today's result. Under the Constitution's separation of powers, however, I believe that it was Congress's role, not this Court's, to amend Title VII.”

A different kind of example is the Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency (2023). Here, the Court significantly limited EPA’s authority to protect certain wetlands under the Clean Water Act, which has serious environmental implications. Notably for our purposes, this conservative ruling was unanimous (9–0), though the justices differed in their reasoning.

So what should one make of these mixed examples? Is the Court under Chief Justice Roberts more conservative than its predecessors? Has it become more conservative since the appointment of the three justices by President Trump, and if so, in what type of cases? And what about ideological splits like 5-4 or 6-3, have they increased over time?

Data. Fortunately, the publicly available Supreme Court Database (SCD), hosted by Washington University in St. Louis, allows researchers to explore precisely these questions. The current version of the database includes all Supreme Court cases from World War II to July 1, 2024 (with an extended version covering decisions from four centuries ago) and classifies each ruling as liberal, conservative, or “unspecifiable”. For example, a decision is coded as liberal if it favors minorities in civil rights cases, supports the defendant in criminal cases, rules against the government in due process cases, or sides with labor over business in union-related disputes. Occasionally, this can give a counterintuitive classification; in Trump v United States (2024), the SCOTUS ruled 6-3 in favor of the individual and is thus coded as ‘liberal.’

Importantly, the SCD also records each justice’s vote, the breakdown of majority and minority opinions, and categorizes the main legal issue using a detailed taxonomy of 271 issue codes (e.g., habeas corpus, antitrust, abortion, torts, privacy) as well as 14 broader issue areas (e.g., Criminal Procedure, First Amendment, Civil Rights, Economic Activity, Due Process). Although there can be occasional misclassifications given the database’s scale and complexity, it is considered comprehensive and is widely used by legal scholars. The database includes 9,277 cases, with only 64 (0.69%) lacking an associated issue.

Robert’s Court. How do SCOTUS decisions under Chief Justice Roberts compare with those of his predecessors? Ignoring unspecifiable cases and coding liberal as 0 and conservative as 1, the average under Roberts is 0.532—meaning 53.2% of cases are conservative. This figure is similar to those from earlier courts: Vinson (49.7%), Berger (54.8%), and Rehnquist (55.2%), with none statistically different from Roberts’ 53.2%. (See Table 1 below.)

Only the Court of Warren, with an average of 32.8% (appointed by Eisenhower, who later called Warren “the biggest damn-fool mistake I ever made”), stands out as markedly liberal, as seen in landmark decisions such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954) which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, or Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) which guaranteed the right to a lawyer in criminal cases, or Miranda v. Arizona (1966) which required police to inform suspects of their rights (Miranda rights) or Loving v. Virginia (1967) which struck down laws banning interracial marriage. Overall, aside from Warren’s Court, the decisions do not appear radically more conservative.

Trump I’s Nominations. Has SCOTUS become more conservative since the nominations of Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett? To check this, we focused on cases decided after Roberts became Chief Justice on October 29, 2005. We partitioned these into two groups: cases decided before April 10, 2017 (the swearing-in date of Justice Gorsuch) and those decided after October 26, 2020 (the swearing-in date of Justice Barrett). We discarded cases between these two dates and those before Roberts took the bench. After removing cases where the issue was not specified or the decision wasn’t coded as liberal/conservative, our sample consisted of 1,128 cases—894 from before any of Trump’s nominations and 234 from afterward.

The good news is that his nominees have not overwhelmingly swung the Court towards conservatism. About 52.68% of decisions were conservative before the nominations, with a further 4.5% increase after—but this change is not statistically significant.

By Issue areas. Although there is no overall change, it still ‘feels’ as if something is amiss—perhaps because we value certain types of cases more highly. Since assigning weights to cases is complex, we next examine changes by issue area as defined in the data. We summarize below the baseline percentage of conservative decisions by issue and the percentage change after the three justices were sworn in.

Most changes are small and not statistically significant. However, two issue areas stand out. For “Due Process,” conservative decisions rose from 18.2% to 70% (an increase of 51.8% and statistically significant). For “Unions,” conservative decisions drop from 60% to 27.3% (a decrease of 32.7%, also statistically significant but not as strongly). These areas—among several others—often involve relatively few observations, which may affect statistical significance.

Liberal/Conservative Splits. We also examined the margin by which majorities prevail—whether decisions occur as 5-4 or 6-3 splits. First, as the proportion of votes in the majority, which range from 50% to 100%, has crept upward over time, consensus has slightly increased. This change is small yet statistically significant. The figure below shows the mean values for majority vote by year as well as the mean of (logit) fitted values.

Second, we assessed whether the share of cases decided by a 5-4 or 6-3 split has changed from before to after Trump’s nominations. This is tricky though, as a 5-4 or 6-3 split does not necessarily mean that the conservative Justices strongarmed their way, as splits can be with a liberal decision too. For example, in June 2012, SCOTUS ruled in a 5-4 split that the individual mandate under Obamacare was constitutional, where Chief Justice Roberts argued the mandate was essentially a tax, a power granted to Congress. Similarly, in Moyle v. United States (2024), three conservative justices — Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett — joined with the liberal justices in a 6-3 decision upholding a lower court injunction preventing Idaho from enforcing its abortion ban in emergencies. But also recall that the 6-3 split in favor of President Trump in the criminal case of Trump v United States is coded as a liberal decision.

As Table 3 shows, about a quarter of cases during this period resulted in 5-4 or 6-3 splits, and such split decisions increased from 23.4% to 29.8%. But when we disaggregate the split cases by liberal or conservative decisions, there is a 12.5% statistically significant increase in split cases when the decision is conservative but not when it is liberal (we also tested this in a probability model for split decisions while controlling individual justice fixed effects with very similar results).

Final thoughts. One important caveat is that the data does not reveal which cases SCOTUS chooses to hear. Nonetheless, the impact of the three Trump nominations on the cases heard has been negligible regarding overall conservative rulings. This is not to say that the new Justices are not conservative or not likely to vote conservatively; rather, it indicates that the Court's overall posture has not radically shifted compared to recent periods. We may take some comfort in that, though we must remain vigilant.

Democracy and justice cannot be taken for granted. Ultimately, while conservative decisions today are more likely to be split along ideological lines, it remains an open question whether this is due to conservative justices imposing their views, liberal justices being more stubborn, or due to the nature of the cases heard by the Supreme Court.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Rulings issued by the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) increasingly appear to be ideologically driven, often splitting along a clear conservative-liberal divide—whether 5–4 when there were five conservative justices, or 6–3 following the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her replacement by the more conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett, appointed by President Trump. The relatively recent Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health ruling in June 2022, where the conservative majority overturned Roe v. Wade by a 6-3 split, underscores this point.

This pattern of partisan alignment contributes to a broader fear, especially in the wake of President Trump’s reelection, that America’s bulwarks of democracy are buckling. From attacks on civil rights, universities, and the press, to a Justice Department willing to arrest sitting judges, Trump’s actions seem designed to destabilize core institutions. At the same time, his roughshod approach to “justice” is almost cynically expected to end up in the courts—particularly at SCOTUS—where many assume the ruling will go his way. The common narrative in progressive circles warns that the Court, stacked with Trump appointees, will support him in any unconstitutional attempt to hold power. While we have no quibble about their assessment that President Trump is a bad hombre who will do his best to do his worst, we are not convinced that SCOTUS will ever do his bidding. And though three of its justices were appointed by Trump and others often align ideologically, SCOTUS has shown itself, at times, to resist political pressure. It may still serve as a vital check on executive overreach. Whether it can fulfill that role is a question worth answering not just with alarm, but with close attention to facts and patterns. But first, some context and examples.

Recall that SCOTUS dismissed Texas v. Pennsylvania in December 2020 because Texas lacked standing in how Pennsylvania (but also other states) conducts its elections. The unsigned order stated: “Texas has not demonstrated a judicially cognizable interest in the manner in which another State conducts its elections.” No Justice supported Texas’s request for relief, though Justices Alito and Thomas would have allowed the complaint to be filed. SCOTUS rejected or refused to hear all other major legal challenges by Trump or his allies to the 2020 elections. This is despite the 6-3 conservative majority in the Court.

Similarly, there are other examples too, and not just those related to elections, that don’t fit the narrative that the three new Justices nominated by Trump will upend all the civil rights, due process, or other liberties we enjoy. Take Bostock v. Clayton County (2020), a landmark civil rights case where, in a 6-3 ruling, the Court ruled the Civil Rights Act protects employees against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. The majority opinion was written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, and while dissenting justices Alito, Thomas, and Kavanaugh are also conservatives, Justice Kavanaugh wrote a separate dissent arguing it should be Congress and not the courts that should add gender and sexual orientation to Title VII. He stated,

“Millions of gay and lesbian Americans have worked hard for many decades to achieve equal treatment in fact and law ... They have advanced powerful policy arguments and can take pride in today's result. Under the Constitution's separation of powers, however, I believe that it was Congress's role, not this Court's, to amend Title VII.”

A different kind of example is the Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency (2023). Here, the Court significantly limited EPA’s authority to protect certain wetlands under the Clean Water Act, which has serious environmental implications. Notably for our purposes, this conservative ruling was unanimous (9–0), though the justices differed in their reasoning.

So what should one make of these mixed examples? Is the Court under Chief Justice Roberts more conservative than its predecessors? Has it become more conservative since the appointment of the three justices by President Trump, and if so, in what type of cases? And what about ideological splits like 5-4 or 6-3, have they increased over time?

Data. Fortunately, the publicly available Supreme Court Database (SCD), hosted by Washington University in St. Louis, allows researchers to explore precisely these questions. The current version of the database includes all Supreme Court cases from World War II to July 1, 2024 (with an extended version covering decisions from four centuries ago) and classifies each ruling as liberal, conservative, or “unspecifiable”. For example, a decision is coded as liberal if it favors minorities in civil rights cases, supports the defendant in criminal cases, rules against the government in due process cases, or sides with labor over business in union-related disputes. Occasionally, this can give a counterintuitive classification; in Trump v United States (2024), the SCOTUS ruled 6-3 in favor of the individual and is thus coded as ‘liberal.’

Importantly, the SCD also records each justice’s vote, the breakdown of majority and minority opinions, and categorizes the main legal issue using a detailed taxonomy of 271 issue codes (e.g., habeas corpus, antitrust, abortion, torts, privacy) as well as 14 broader issue areas (e.g., Criminal Procedure, First Amendment, Civil Rights, Economic Activity, Due Process). Although there can be occasional misclassifications given the database’s scale and complexity, it is considered comprehensive and is widely used by legal scholars. The database includes 9,277 cases, with only 64 (0.69%) lacking an associated issue.

Robert’s Court. How do SCOTUS decisions under Chief Justice Roberts compare with those of his predecessors? Ignoring unspecifiable cases and coding liberal as 0 and conservative as 1, the average under Roberts is 0.532—meaning 53.2% of cases are conservative. This figure is similar to those from earlier courts: Vinson (49.7%), Berger (54.8%), and Rehnquist (55.2%), with none statistically different from Roberts’ 53.2%. (See Table 1 below.)

Only the Court of Warren, with an average of 32.8% (appointed by Eisenhower, who later called Warren “the biggest damn-fool mistake I ever made”), stands out as markedly liberal, as seen in landmark decisions such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954) which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, or Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) which guaranteed the right to a lawyer in criminal cases, or Miranda v. Arizona (1966) which required police to inform suspects of their rights (Miranda rights) or Loving v. Virginia (1967) which struck down laws banning interracial marriage. Overall, aside from Warren’s Court, the decisions do not appear radically more conservative.

Trump I’s Nominations. Has SCOTUS become more conservative since the nominations of Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett? To check this, we focused on cases decided after Roberts became Chief Justice on October 29, 2005. We partitioned these into two groups: cases decided before April 10, 2017 (the swearing-in date of Justice Gorsuch) and those decided after October 26, 2020 (the swearing-in date of Justice Barrett). We discarded cases between these two dates and those before Roberts took the bench. After removing cases where the issue was not specified or the decision wasn’t coded as liberal/conservative, our sample consisted of 1,128 cases—894 from before any of Trump’s nominations and 234 from afterward.

The good news is that his nominees have not overwhelmingly swung the Court towards conservatism. About 52.68% of decisions were conservative before the nominations, with a further 4.5% increase after—but this change is not statistically significant.

By Issue areas. Although there is no overall change, it still ‘feels’ as if something is amiss—perhaps because we value certain types of cases more highly. Since assigning weights to cases is complex, we next examine changes by issue area as defined in the data. We summarize below the baseline percentage of conservative decisions by issue and the percentage change after the three justices were sworn in.

Most changes are small and not statistically significant. However, two issue areas stand out. For “Due Process,” conservative decisions rose from 18.2% to 70% (an increase of 51.8% and statistically significant). For “Unions,” conservative decisions drop from 60% to 27.3% (a decrease of 32.7%, also statistically significant but not as strongly). These areas—among several others—often involve relatively few observations, which may affect statistical significance.

Liberal/Conservative Splits. We also examined the margin by which majorities prevail—whether decisions occur as 5-4 or 6-3 splits. First, as the proportion of votes in the majority, which range from 50% to 100%, has crept upward over time, consensus has slightly increased. This change is small yet statistically significant. The figure below shows the mean values for majority vote by year as well as the mean of (logit) fitted values.

Second, we assessed whether the share of cases decided by a 5-4 or 6-3 split has changed from before to after Trump’s nominations. This is tricky though, as a 5-4 or 6-3 split does not necessarily mean that the conservative Justices strongarmed their way, as splits can be with a liberal decision too. For example, in June 2012, SCOTUS ruled in a 5-4 split that the individual mandate under Obamacare was constitutional, where Chief Justice Roberts argued the mandate was essentially a tax, a power granted to Congress. Similarly, in Moyle v. United States (2024), three conservative justices — Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett — joined with the liberal justices in a 6-3 decision upholding a lower court injunction preventing Idaho from enforcing its abortion ban in emergencies. But also recall that the 6-3 split in favor of President Trump in the criminal case of Trump v United States is coded as a liberal decision.

As Table 3 shows, about a quarter of cases during this period resulted in 5-4 or 6-3 splits, and such split decisions increased from 23.4% to 29.8%. But when we disaggregate the split cases by liberal or conservative decisions, there is a 12.5% statistically significant increase in split cases when the decision is conservative but not when it is liberal (we also tested this in a probability model for split decisions while controlling individual justice fixed effects with very similar results).

Final thoughts. One important caveat is that the data does not reveal which cases SCOTUS chooses to hear. Nonetheless, the impact of the three Trump nominations on the cases heard has been negligible regarding overall conservative rulings. This is not to say that the new Justices are not conservative or not likely to vote conservatively; rather, it indicates that the Court's overall posture has not radically shifted compared to recent periods. We may take some comfort in that, though we must remain vigilant.

Democracy and justice cannot be taken for granted. Ultimately, while conservative decisions today are more likely to be split along ideological lines, it remains an open question whether this is due to conservative justices imposing their views, liberal justices being more stubborn, or due to the nature of the cases heard by the Supreme Court.

Rulings issued by the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) increasingly appear to be ideologically driven, often splitting along a clear conservative-liberal divide—whether 5–4 when there were five conservative justices, or 6–3 following the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her replacement by the more conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett, appointed by President Trump. The relatively recent Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health ruling in June 2022, where the conservative majority overturned Roe v. Wade by a 6-3 split, underscores this point.

This pattern of partisan alignment contributes to a broader fear, especially in the wake of President Trump’s reelection, that America’s bulwarks of democracy are buckling. From attacks on civil rights, universities, and the press, to a Justice Department willing to arrest sitting judges, Trump’s actions seem designed to destabilize core institutions. At the same time, his roughshod approach to “justice” is almost cynically expected to end up in the courts—particularly at SCOTUS—where many assume the ruling will go his way. The common narrative in progressive circles warns that the Court, stacked with Trump appointees, will support him in any unconstitutional attempt to hold power. While we have no quibble about their assessment that President Trump is a bad hombre who will do his best to do his worst, we are not convinced that SCOTUS will ever do his bidding. And though three of its justices were appointed by Trump and others often align ideologically, SCOTUS has shown itself, at times, to resist political pressure. It may still serve as a vital check on executive overreach. Whether it can fulfill that role is a question worth answering not just with alarm, but with close attention to facts and patterns. But first, some context and examples.

Recall that SCOTUS dismissed Texas v. Pennsylvania in December 2020 because Texas lacked standing in how Pennsylvania (but also other states) conducts its elections. The unsigned order stated: “Texas has not demonstrated a judicially cognizable interest in the manner in which another State conducts its elections.” No Justice supported Texas’s request for relief, though Justices Alito and Thomas would have allowed the complaint to be filed. SCOTUS rejected or refused to hear all other major legal challenges by Trump or his allies to the 2020 elections. This is despite the 6-3 conservative majority in the Court.

Similarly, there are other examples too, and not just those related to elections, that don’t fit the narrative that the three new Justices nominated by Trump will upend all the civil rights, due process, or other liberties we enjoy. Take Bostock v. Clayton County (2020), a landmark civil rights case where, in a 6-3 ruling, the Court ruled the Civil Rights Act protects employees against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. The majority opinion was written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, and while dissenting justices Alito, Thomas, and Kavanaugh are also conservatives, Justice Kavanaugh wrote a separate dissent arguing it should be Congress and not the courts that should add gender and sexual orientation to Title VII. He stated,

“Millions of gay and lesbian Americans have worked hard for many decades to achieve equal treatment in fact and law ... They have advanced powerful policy arguments and can take pride in today's result. Under the Constitution's separation of powers, however, I believe that it was Congress's role, not this Court's, to amend Title VII.”

A different kind of example is the Sackett v. Environmental Protection Agency (2023). Here, the Court significantly limited EPA’s authority to protect certain wetlands under the Clean Water Act, which has serious environmental implications. Notably for our purposes, this conservative ruling was unanimous (9–0), though the justices differed in their reasoning.

So what should one make of these mixed examples? Is the Court under Chief Justice Roberts more conservative than its predecessors? Has it become more conservative since the appointment of the three justices by President Trump, and if so, in what type of cases? And what about ideological splits like 5-4 or 6-3, have they increased over time?

Data. Fortunately, the publicly available Supreme Court Database (SCD), hosted by Washington University in St. Louis, allows researchers to explore precisely these questions. The current version of the database includes all Supreme Court cases from World War II to July 1, 2024 (with an extended version covering decisions from four centuries ago) and classifies each ruling as liberal, conservative, or “unspecifiable”. For example, a decision is coded as liberal if it favors minorities in civil rights cases, supports the defendant in criminal cases, rules against the government in due process cases, or sides with labor over business in union-related disputes. Occasionally, this can give a counterintuitive classification; in Trump v United States (2024), the SCOTUS ruled 6-3 in favor of the individual and is thus coded as ‘liberal.’

Importantly, the SCD also records each justice’s vote, the breakdown of majority and minority opinions, and categorizes the main legal issue using a detailed taxonomy of 271 issue codes (e.g., habeas corpus, antitrust, abortion, torts, privacy) as well as 14 broader issue areas (e.g., Criminal Procedure, First Amendment, Civil Rights, Economic Activity, Due Process). Although there can be occasional misclassifications given the database’s scale and complexity, it is considered comprehensive and is widely used by legal scholars. The database includes 9,277 cases, with only 64 (0.69%) lacking an associated issue.

Robert’s Court. How do SCOTUS decisions under Chief Justice Roberts compare with those of his predecessors? Ignoring unspecifiable cases and coding liberal as 0 and conservative as 1, the average under Roberts is 0.532—meaning 53.2% of cases are conservative. This figure is similar to those from earlier courts: Vinson (49.7%), Berger (54.8%), and Rehnquist (55.2%), with none statistically different from Roberts’ 53.2%. (See Table 1 below.)

Only the Court of Warren, with an average of 32.8% (appointed by Eisenhower, who later called Warren “the biggest damn-fool mistake I ever made”), stands out as markedly liberal, as seen in landmark decisions such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954) which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, or Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) which guaranteed the right to a lawyer in criminal cases, or Miranda v. Arizona (1966) which required police to inform suspects of their rights (Miranda rights) or Loving v. Virginia (1967) which struck down laws banning interracial marriage. Overall, aside from Warren’s Court, the decisions do not appear radically more conservative.

Trump I’s Nominations. Has SCOTUS become more conservative since the nominations of Justices Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett? To check this, we focused on cases decided after Roberts became Chief Justice on October 29, 2005. We partitioned these into two groups: cases decided before April 10, 2017 (the swearing-in date of Justice Gorsuch) and those decided after October 26, 2020 (the swearing-in date of Justice Barrett). We discarded cases between these two dates and those before Roberts took the bench. After removing cases where the issue was not specified or the decision wasn’t coded as liberal/conservative, our sample consisted of 1,128 cases—894 from before any of Trump’s nominations and 234 from afterward.

The good news is that his nominees have not overwhelmingly swung the Court towards conservatism. About 52.68% of decisions were conservative before the nominations, with a further 4.5% increase after—but this change is not statistically significant.

By Issue areas. Although there is no overall change, it still ‘feels’ as if something is amiss—perhaps because we value certain types of cases more highly. Since assigning weights to cases is complex, we next examine changes by issue area as defined in the data. We summarize below the baseline percentage of conservative decisions by issue and the percentage change after the three justices were sworn in.

Most changes are small and not statistically significant. However, two issue areas stand out. For “Due Process,” conservative decisions rose from 18.2% to 70% (an increase of 51.8% and statistically significant). For “Unions,” conservative decisions drop from 60% to 27.3% (a decrease of 32.7%, also statistically significant but not as strongly). These areas—among several others—often involve relatively few observations, which may affect statistical significance.

Liberal/Conservative Splits. We also examined the margin by which majorities prevail—whether decisions occur as 5-4 or 6-3 splits. First, as the proportion of votes in the majority, which range from 50% to 100%, has crept upward over time, consensus has slightly increased. This change is small yet statistically significant. The figure below shows the mean values for majority vote by year as well as the mean of (logit) fitted values.

Second, we assessed whether the share of cases decided by a 5-4 or 6-3 split has changed from before to after Trump’s nominations. This is tricky though, as a 5-4 or 6-3 split does not necessarily mean that the conservative Justices strongarmed their way, as splits can be with a liberal decision too. For example, in June 2012, SCOTUS ruled in a 5-4 split that the individual mandate under Obamacare was constitutional, where Chief Justice Roberts argued the mandate was essentially a tax, a power granted to Congress. Similarly, in Moyle v. United States (2024), three conservative justices — Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett — joined with the liberal justices in a 6-3 decision upholding a lower court injunction preventing Idaho from enforcing its abortion ban in emergencies. But also recall that the 6-3 split in favor of President Trump in the criminal case of Trump v United States is coded as a liberal decision.

As Table 3 shows, about a quarter of cases during this period resulted in 5-4 or 6-3 splits, and such split decisions increased from 23.4% to 29.8%. But when we disaggregate the split cases by liberal or conservative decisions, there is a 12.5% statistically significant increase in split cases when the decision is conservative but not when it is liberal (we also tested this in a probability model for split decisions while controlling individual justice fixed effects with very similar results).

Final thoughts. One important caveat is that the data does not reveal which cases SCOTUS chooses to hear. Nonetheless, the impact of the three Trump nominations on the cases heard has been negligible regarding overall conservative rulings. This is not to say that the new Justices are not conservative or not likely to vote conservatively; rather, it indicates that the Court's overall posture has not radically shifted compared to recent periods. We may take some comfort in that, though we must remain vigilant.

Democracy and justice cannot be taken for granted. Ultimately, while conservative decisions today are more likely to be split along ideological lines, it remains an open question whether this is due to conservative justices imposing their views, liberal justices being more stubborn, or due to the nature of the cases heard by the Supreme Court.