SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Guatemalan pro-democracy protesters block a road.

Supporters of embattled anti-corruption President-elect Bernardo Arévalo are demanding the resignation of the prosecutors targeting him to ensure that democracy and the will of the people are upheld.

It is Wednesday, September 4, 2023, and the town of Panajachel (known locally as Pana) is celebrating is annual fair. Much of the town has come out to enjoy the fairground rides, the delicious street food, the magical but wildly over-the-top firework displays, and in traditional Guatemalan style, the joyous yet incredibly loud bands playing until late into the morning.

Due to their proximity to the lake, the towns surrounding Lago de Atitlán are relatively cut off from main cities. There are only two roads in and out, and even by Guatemalan standards, the mountain roads are not for the faint hearted. Panajachel is a jaw-droppingly beautiful tourist town with a majority Indigenous population, rich culture, and a constant flow of visitors both nationally and from all around the world.

Protests, marches, and roadblocks had already begun in the rest of the country earlier in the week, and Panajachel was quick to leave the festivities of the fair behind, join in, unite, and show their solidarity starting in the early hours of Thursday.

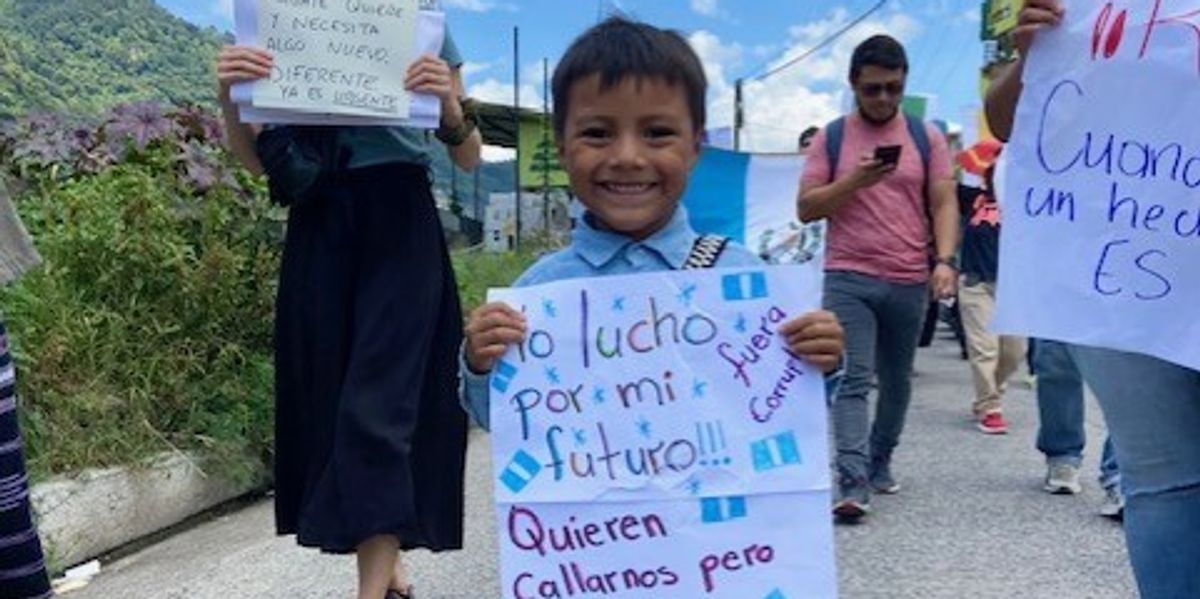

A Guatemalan child holds up a protest sign.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

Trouble started back in August during the 2023 Presidential election where the now President-elect Bernardo Arévalo and his Movimiento Semilla party (the Seed Movement) won with 61% of the vote. His anti-corruption campaign attracted voters who have witnessed for decades the decline in democracy and the increasing entanglement of the government in cases of fraud, deception, and abuse of power.

As it became clear that Arévalo was to be the front runner, Attorney General María Consuelo Porras and her office commenced an investigation into his party. They claim that the original signatures to form the Seed Movement back in 2017 were fraudulent. Their offices and headquarters have since been raided, and vote tallies have been seized from Guatemala’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal.

In May 2022, Porras was sanctioned by the U.S. government for her involvement in corruption and repeatedly obstructing anti-corruption investigations. During her tenure, 24 judges and prosecutors in Guatemala have been forced into exile.

Guatemalans are famed for their incredible resilience, strength, and determination. They will not stop until Porras and the other prosecutors have stepped down.

Frustrated communities took matters into their own hands after the country’s highest court upheld a move to suspend Arévalo’s party over alleged voter registration fraud, thereby preventing his inauguration in January 2024. Without his party, he is effectively powerless.

Arévalo has labelled these actions an attempted coup d’etat, and his supporters are demanding the resignation of Porras and the other prosecutors to ensure that democracy and the will of the people are upheld.

Many have noted the silence of current President Alejandro Giammattei who didn’t make his first speech on the topic until Monday October 9—one week after the demonstrations began. No mention of Porras or her resignation was made. He did however confirm there will be a clamp down on protesters, that leaders of the roadblocks will be arrested, and then went on to claim that the demonstrations were being funded and guided by foreigners.

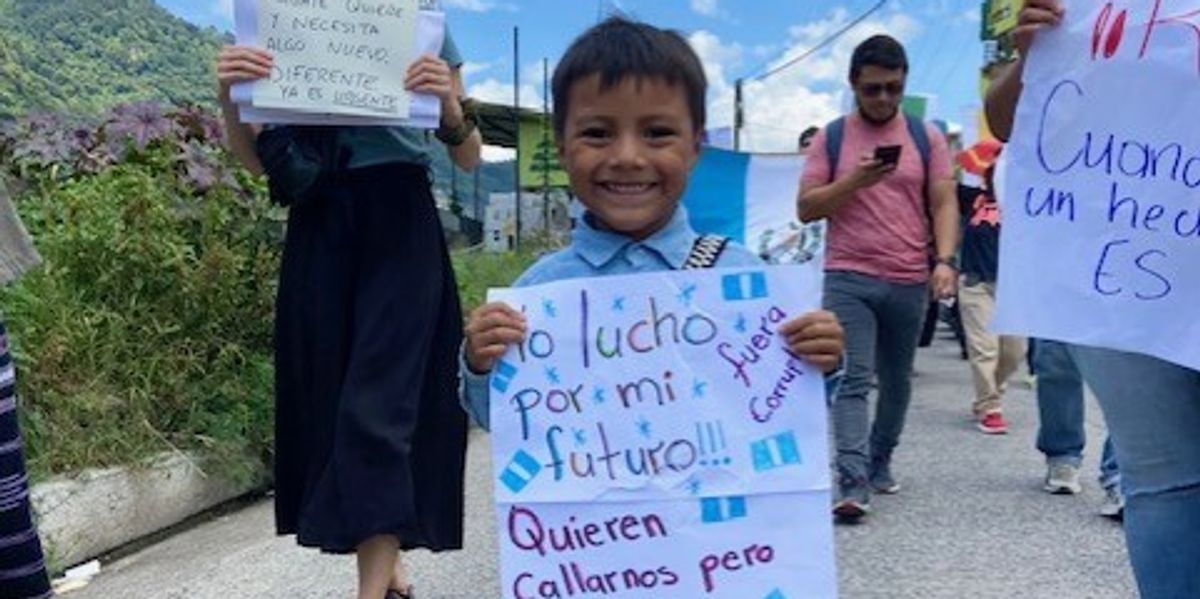

A protest sign calls for an end to corruption.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

Guatemala scored only 24 points out of 100 on the 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index reported by Transparency International. This places them firmly in the bottom 30, level with Afghanistan, Cambodia, and the Central African Republic.

Corruption is currently at unprecedented levels following years of authoritarian governance which is punishing prosecutors and judges for investigating organized crime.

In the progressive weakening of democratic institutions, those whose have, let’s say, crossed the wrong paths, have been targeted with fraudulent lawsuits, unmotivated firings, and threats of violence.

The 10 Years of Spring that followed the revolution in 1944 were the only respite from dictatorships in that whole period up until 1996.

The fight against corruption in Guatemala is nothing new; however, in recent years, the campaign against anti-corruption efforts has intensified. Back in 2007, the United Nations formed what was known as the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), acting as an independent anti-corruption body to bring to justice the various criminal groups who had controlled the country after three decades of civil war.

The CICIG had to create new institutions as so many key offices were under the grips of organized crime, including the police, the Public Ministry, and the existing court system. Their achievements were incredibly successful, including the well-known case of La Línea. Under the administration of Otto Pérez Molina, a number of politicians were accused of involvement in a large smuggling ring centered around customs involving huge kickbacks of almost $40 million. Large scale demonstrations ensued and ultimately led to the resignation of Molina and his vice-president Baldetti.

Later in 2018, President Jimmy Morales, whose campaign slogan labelled him “neither corrupt nor a thief,” closed the CICIG after they began an investigation into his family.

For decades there has been a disregard for the Guatemalan public by those in power. The money entering the country was simply not reaching the people most in need and merely enriched the few with lavish lifestyles that most Guatemalans can only imagine.

For perspective, most people in the country are employed in the informal agricultural sector; as a result, 55% of the population live below the poverty line. According to the World Food Programme, almost half of Guatemalan children under the age of 5 are chronically malnourished; additionally, 41% of teenagers aged 13-18 are not in formal education.

For the entire period from the 19th century until 1944, Guatemala was ruled by dictators. During this time a large proportion of the Indigenous population were violently forced from their lands. Through lack of other opportunities and the need to survive, they were ‘employed’ by the new foreign landowners to work the plantations under brutal conditions, for next to no compensation.

The 10 Years of Spring that followed the revolution in 1944 were the only respite from dictatorships in that whole period up until 1996. For many years attacks on human rights defenders and trade unionists have been commonplace. This, coupled with the closure of the CICIG, has left Guatemalans largely voiceless and repressed.

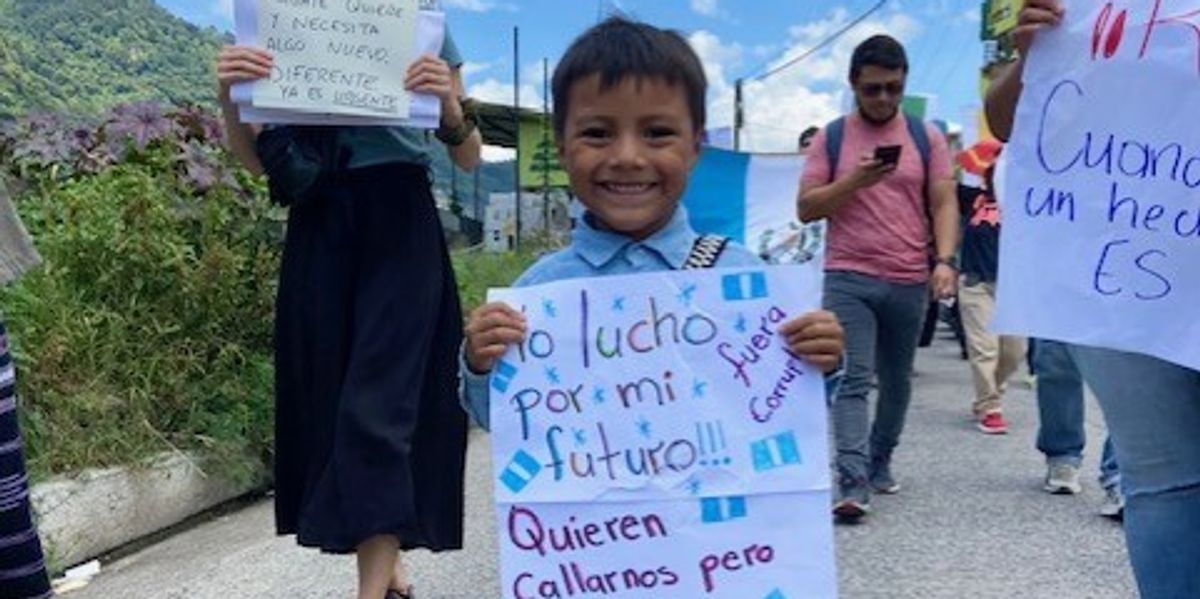

Protesters gather at a road blockade.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

Due to the geographical nature of Panajachel and the nearby towns, the effects of the roadblocks have hit much faster as supplies such as food, basic commodities, petrol, and even cash has quickly diminished. In a country which does not have potable water, the supply of large, purified water bottles is absolutely vital.

The lack of new fresh fruit and vegetables entering the town, coupled with the loss of income, has forced market traders to increase their prices, sometimes threefold, and beyond the means of local people. Businesses have been allowed to open but only for 2-3 hours from six in the morning; during this time long lines have formed outside of the market and some supermarkets.

People here rely on LPG gas cylinders for their cooking, and again the short supply and the lack of ability to transport them has left many stranded. As the cash machines ran dry, supermarkets became the only option to purchase goods for those lucky enough to have money in the bank, and access to a bank card.

Hardship is nothing new to Guatemalans, and, in the eyes of the vast majority, the fight for democracy is worth the struggle.

On the first day of the protests the entire town was left without electricity until 7 pm. It remains unconfirmed whether the electricity was turned off on purpose as a warning to activists and protesters, or simply if the engineers were not able to pass through the roadblocks to make their repairs.

Reports by the Director of Civil Aeronautics confirmed on Monday that the country’s only international airport La Aurora has ran out of fuel and is no longer able to supply the aircraft arriving at the airport, an issue which has since been resolved with the help of El Salvador.

Most Guatemalans will now be suffering the effects of these demonstrations either through the inability to work, the rising costs of goods, dwindling cash, and eventually hunger. Despite this, the people in the streets and the dedicated activists at the roadblocks are jovial; there are friendly exchanges, smiles, and a real feeling of hope. Hardship is nothing new to Guatemalans, and, in the eyes of the vast majority, the fight for democracy is worth the struggle.

Protesters march down a street with drums.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

As of October 8, there are 68 official road blockages on major transport routes throughout the country created and enforced by everyday citizens. This number is growing daily, and most likely official numbers underestimate the true extent as many smaller rural road blocks have not been listed. Tens of thousands of Guatemalans have been protesting peacefully for days without respite. Imagine a nationwide sit-in. Not even the heavy rains have managed to deter spirits. The protests have taken the form of marches and the gathering of large crowds at main transport arteries. Canopies have been set up to provide shelter for the protesters who have brought BBQs, food, speakers, and microphones. Even musicians have joined in and performed through the night to keep moods high.

Guatemalans are famed for their incredible resilience, strength, and determination. They will not stop until Porras and the other prosecutors have stepped down. This is how desperate the people are for change.

Officials have released a statement declaring that all attempts to block transit routes are illegal, and that force will be used if necessary to clear the roads. So far there has been no such escalation, despite an order for the government to enforce this ruling. The government has explicitly refused to call for a state of emergency.

Loss of income, hunger, or any other implications are merely slight inconveniences for Guatemalans who are sadly used to having to stand up for their own rights.

Panajachel is home to a large community of foreigners who have shown their solidarity with local people by either joining the marches, sharing knowledge on social media community groups, donating food and supplies to protesters, or simply respecting the will of the Guatemalan people. It is important for foreigners to share their experiences to give this situation the international attention it deserves, in what has largely been ignored by western media.

Of note, officials have warned that if foreigners become involved in protests or at roadblocks, they risk deportation or being denied entry to the country in the future. So far there has been no evidence of this, and local police in Panajachel offered their assistance to marchers over the weekend, who were a mix of local and international supporters. That said, due diligence should be used at all times for everyone looking to show their solidarity.

Guatemalans are seizing this opportunity to fight for real change. Loss of income, hunger, or any other implications are merely slight inconveniences for Guatemalans who are sadly used to having to stand up for their own rights.

The Organisation of American States on Saturday named the representatives who will mediate between protesters and officials with the aim of achieving an orderly transfer of power. That said, escalations of violence to remove protesters from the streets is expected to commence on Monday.

This piece was originally published in Better World Info.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

It is Wednesday, September 4, 2023, and the town of Panajachel (known locally as Pana) is celebrating is annual fair. Much of the town has come out to enjoy the fairground rides, the delicious street food, the magical but wildly over-the-top firework displays, and in traditional Guatemalan style, the joyous yet incredibly loud bands playing until late into the morning.

Due to their proximity to the lake, the towns surrounding Lago de Atitlán are relatively cut off from main cities. There are only two roads in and out, and even by Guatemalan standards, the mountain roads are not for the faint hearted. Panajachel is a jaw-droppingly beautiful tourist town with a majority Indigenous population, rich culture, and a constant flow of visitors both nationally and from all around the world.

Protests, marches, and roadblocks had already begun in the rest of the country earlier in the week, and Panajachel was quick to leave the festivities of the fair behind, join in, unite, and show their solidarity starting in the early hours of Thursday.

A Guatemalan child holds up a protest sign.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

Trouble started back in August during the 2023 Presidential election where the now President-elect Bernardo Arévalo and his Movimiento Semilla party (the Seed Movement) won with 61% of the vote. His anti-corruption campaign attracted voters who have witnessed for decades the decline in democracy and the increasing entanglement of the government in cases of fraud, deception, and abuse of power.

As it became clear that Arévalo was to be the front runner, Attorney General María Consuelo Porras and her office commenced an investigation into his party. They claim that the original signatures to form the Seed Movement back in 2017 were fraudulent. Their offices and headquarters have since been raided, and vote tallies have been seized from Guatemala’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal.

In May 2022, Porras was sanctioned by the U.S. government for her involvement in corruption and repeatedly obstructing anti-corruption investigations. During her tenure, 24 judges and prosecutors in Guatemala have been forced into exile.

Guatemalans are famed for their incredible resilience, strength, and determination. They will not stop until Porras and the other prosecutors have stepped down.

Frustrated communities took matters into their own hands after the country’s highest court upheld a move to suspend Arévalo’s party over alleged voter registration fraud, thereby preventing his inauguration in January 2024. Without his party, he is effectively powerless.

Arévalo has labelled these actions an attempted coup d’etat, and his supporters are demanding the resignation of Porras and the other prosecutors to ensure that democracy and the will of the people are upheld.

Many have noted the silence of current President Alejandro Giammattei who didn’t make his first speech on the topic until Monday October 9—one week after the demonstrations began. No mention of Porras or her resignation was made. He did however confirm there will be a clamp down on protesters, that leaders of the roadblocks will be arrested, and then went on to claim that the demonstrations were being funded and guided by foreigners.

A protest sign calls for an end to corruption.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

Guatemala scored only 24 points out of 100 on the 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index reported by Transparency International. This places them firmly in the bottom 30, level with Afghanistan, Cambodia, and the Central African Republic.

Corruption is currently at unprecedented levels following years of authoritarian governance which is punishing prosecutors and judges for investigating organized crime.

In the progressive weakening of democratic institutions, those whose have, let’s say, crossed the wrong paths, have been targeted with fraudulent lawsuits, unmotivated firings, and threats of violence.

The 10 Years of Spring that followed the revolution in 1944 were the only respite from dictatorships in that whole period up until 1996.

The fight against corruption in Guatemala is nothing new; however, in recent years, the campaign against anti-corruption efforts has intensified. Back in 2007, the United Nations formed what was known as the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), acting as an independent anti-corruption body to bring to justice the various criminal groups who had controlled the country after three decades of civil war.

The CICIG had to create new institutions as so many key offices were under the grips of organized crime, including the police, the Public Ministry, and the existing court system. Their achievements were incredibly successful, including the well-known case of La Línea. Under the administration of Otto Pérez Molina, a number of politicians were accused of involvement in a large smuggling ring centered around customs involving huge kickbacks of almost $40 million. Large scale demonstrations ensued and ultimately led to the resignation of Molina and his vice-president Baldetti.

Later in 2018, President Jimmy Morales, whose campaign slogan labelled him “neither corrupt nor a thief,” closed the CICIG after they began an investigation into his family.

For decades there has been a disregard for the Guatemalan public by those in power. The money entering the country was simply not reaching the people most in need and merely enriched the few with lavish lifestyles that most Guatemalans can only imagine.

For perspective, most people in the country are employed in the informal agricultural sector; as a result, 55% of the population live below the poverty line. According to the World Food Programme, almost half of Guatemalan children under the age of 5 are chronically malnourished; additionally, 41% of teenagers aged 13-18 are not in formal education.

For the entire period from the 19th century until 1944, Guatemala was ruled by dictators. During this time a large proportion of the Indigenous population were violently forced from their lands. Through lack of other opportunities and the need to survive, they were ‘employed’ by the new foreign landowners to work the plantations under brutal conditions, for next to no compensation.

The 10 Years of Spring that followed the revolution in 1944 were the only respite from dictatorships in that whole period up until 1996. For many years attacks on human rights defenders and trade unionists have been commonplace. This, coupled with the closure of the CICIG, has left Guatemalans largely voiceless and repressed.

Protesters gather at a road blockade.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

Due to the geographical nature of Panajachel and the nearby towns, the effects of the roadblocks have hit much faster as supplies such as food, basic commodities, petrol, and even cash has quickly diminished. In a country which does not have potable water, the supply of large, purified water bottles is absolutely vital.

The lack of new fresh fruit and vegetables entering the town, coupled with the loss of income, has forced market traders to increase their prices, sometimes threefold, and beyond the means of local people. Businesses have been allowed to open but only for 2-3 hours from six in the morning; during this time long lines have formed outside of the market and some supermarkets.

People here rely on LPG gas cylinders for their cooking, and again the short supply and the lack of ability to transport them has left many stranded. As the cash machines ran dry, supermarkets became the only option to purchase goods for those lucky enough to have money in the bank, and access to a bank card.

Hardship is nothing new to Guatemalans, and, in the eyes of the vast majority, the fight for democracy is worth the struggle.

On the first day of the protests the entire town was left without electricity until 7 pm. It remains unconfirmed whether the electricity was turned off on purpose as a warning to activists and protesters, or simply if the engineers were not able to pass through the roadblocks to make their repairs.

Reports by the Director of Civil Aeronautics confirmed on Monday that the country’s only international airport La Aurora has ran out of fuel and is no longer able to supply the aircraft arriving at the airport, an issue which has since been resolved with the help of El Salvador.

Most Guatemalans will now be suffering the effects of these demonstrations either through the inability to work, the rising costs of goods, dwindling cash, and eventually hunger. Despite this, the people in the streets and the dedicated activists at the roadblocks are jovial; there are friendly exchanges, smiles, and a real feeling of hope. Hardship is nothing new to Guatemalans, and, in the eyes of the vast majority, the fight for democracy is worth the struggle.

Protesters march down a street with drums.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

As of October 8, there are 68 official road blockages on major transport routes throughout the country created and enforced by everyday citizens. This number is growing daily, and most likely official numbers underestimate the true extent as many smaller rural road blocks have not been listed. Tens of thousands of Guatemalans have been protesting peacefully for days without respite. Imagine a nationwide sit-in. Not even the heavy rains have managed to deter spirits. The protests have taken the form of marches and the gathering of large crowds at main transport arteries. Canopies have been set up to provide shelter for the protesters who have brought BBQs, food, speakers, and microphones. Even musicians have joined in and performed through the night to keep moods high.

Guatemalans are famed for their incredible resilience, strength, and determination. They will not stop until Porras and the other prosecutors have stepped down. This is how desperate the people are for change.

Officials have released a statement declaring that all attempts to block transit routes are illegal, and that force will be used if necessary to clear the roads. So far there has been no such escalation, despite an order for the government to enforce this ruling. The government has explicitly refused to call for a state of emergency.

Loss of income, hunger, or any other implications are merely slight inconveniences for Guatemalans who are sadly used to having to stand up for their own rights.

Panajachel is home to a large community of foreigners who have shown their solidarity with local people by either joining the marches, sharing knowledge on social media community groups, donating food and supplies to protesters, or simply respecting the will of the Guatemalan people. It is important for foreigners to share their experiences to give this situation the international attention it deserves, in what has largely been ignored by western media.

Of note, officials have warned that if foreigners become involved in protests or at roadblocks, they risk deportation or being denied entry to the country in the future. So far there has been no evidence of this, and local police in Panajachel offered their assistance to marchers over the weekend, who were a mix of local and international supporters. That said, due diligence should be used at all times for everyone looking to show their solidarity.

Guatemalans are seizing this opportunity to fight for real change. Loss of income, hunger, or any other implications are merely slight inconveniences for Guatemalans who are sadly used to having to stand up for their own rights.

The Organisation of American States on Saturday named the representatives who will mediate between protesters and officials with the aim of achieving an orderly transfer of power. That said, escalations of violence to remove protesters from the streets is expected to commence on Monday.

This piece was originally published in Better World Info.

It is Wednesday, September 4, 2023, and the town of Panajachel (known locally as Pana) is celebrating is annual fair. Much of the town has come out to enjoy the fairground rides, the delicious street food, the magical but wildly over-the-top firework displays, and in traditional Guatemalan style, the joyous yet incredibly loud bands playing until late into the morning.

Due to their proximity to the lake, the towns surrounding Lago de Atitlán are relatively cut off from main cities. There are only two roads in and out, and even by Guatemalan standards, the mountain roads are not for the faint hearted. Panajachel is a jaw-droppingly beautiful tourist town with a majority Indigenous population, rich culture, and a constant flow of visitors both nationally and from all around the world.

Protests, marches, and roadblocks had already begun in the rest of the country earlier in the week, and Panajachel was quick to leave the festivities of the fair behind, join in, unite, and show their solidarity starting in the early hours of Thursday.

A Guatemalan child holds up a protest sign.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

Trouble started back in August during the 2023 Presidential election where the now President-elect Bernardo Arévalo and his Movimiento Semilla party (the Seed Movement) won with 61% of the vote. His anti-corruption campaign attracted voters who have witnessed for decades the decline in democracy and the increasing entanglement of the government in cases of fraud, deception, and abuse of power.

As it became clear that Arévalo was to be the front runner, Attorney General María Consuelo Porras and her office commenced an investigation into his party. They claim that the original signatures to form the Seed Movement back in 2017 were fraudulent. Their offices and headquarters have since been raided, and vote tallies have been seized from Guatemala’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal.

In May 2022, Porras was sanctioned by the U.S. government for her involvement in corruption and repeatedly obstructing anti-corruption investigations. During her tenure, 24 judges and prosecutors in Guatemala have been forced into exile.

Guatemalans are famed for their incredible resilience, strength, and determination. They will not stop until Porras and the other prosecutors have stepped down.

Frustrated communities took matters into their own hands after the country’s highest court upheld a move to suspend Arévalo’s party over alleged voter registration fraud, thereby preventing his inauguration in January 2024. Without his party, he is effectively powerless.

Arévalo has labelled these actions an attempted coup d’etat, and his supporters are demanding the resignation of Porras and the other prosecutors to ensure that democracy and the will of the people are upheld.

Many have noted the silence of current President Alejandro Giammattei who didn’t make his first speech on the topic until Monday October 9—one week after the demonstrations began. No mention of Porras or her resignation was made. He did however confirm there will be a clamp down on protesters, that leaders of the roadblocks will be arrested, and then went on to claim that the demonstrations were being funded and guided by foreigners.

A protest sign calls for an end to corruption.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

Guatemala scored only 24 points out of 100 on the 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index reported by Transparency International. This places them firmly in the bottom 30, level with Afghanistan, Cambodia, and the Central African Republic.

Corruption is currently at unprecedented levels following years of authoritarian governance which is punishing prosecutors and judges for investigating organized crime.

In the progressive weakening of democratic institutions, those whose have, let’s say, crossed the wrong paths, have been targeted with fraudulent lawsuits, unmotivated firings, and threats of violence.

The 10 Years of Spring that followed the revolution in 1944 were the only respite from dictatorships in that whole period up until 1996.

The fight against corruption in Guatemala is nothing new; however, in recent years, the campaign against anti-corruption efforts has intensified. Back in 2007, the United Nations formed what was known as the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), acting as an independent anti-corruption body to bring to justice the various criminal groups who had controlled the country after three decades of civil war.

The CICIG had to create new institutions as so many key offices were under the grips of organized crime, including the police, the Public Ministry, and the existing court system. Their achievements were incredibly successful, including the well-known case of La Línea. Under the administration of Otto Pérez Molina, a number of politicians were accused of involvement in a large smuggling ring centered around customs involving huge kickbacks of almost $40 million. Large scale demonstrations ensued and ultimately led to the resignation of Molina and his vice-president Baldetti.

Later in 2018, President Jimmy Morales, whose campaign slogan labelled him “neither corrupt nor a thief,” closed the CICIG after they began an investigation into his family.

For decades there has been a disregard for the Guatemalan public by those in power. The money entering the country was simply not reaching the people most in need and merely enriched the few with lavish lifestyles that most Guatemalans can only imagine.

For perspective, most people in the country are employed in the informal agricultural sector; as a result, 55% of the population live below the poverty line. According to the World Food Programme, almost half of Guatemalan children under the age of 5 are chronically malnourished; additionally, 41% of teenagers aged 13-18 are not in formal education.

For the entire period from the 19th century until 1944, Guatemala was ruled by dictators. During this time a large proportion of the Indigenous population were violently forced from their lands. Through lack of other opportunities and the need to survive, they were ‘employed’ by the new foreign landowners to work the plantations under brutal conditions, for next to no compensation.

The 10 Years of Spring that followed the revolution in 1944 were the only respite from dictatorships in that whole period up until 1996. For many years attacks on human rights defenders and trade unionists have been commonplace. This, coupled with the closure of the CICIG, has left Guatemalans largely voiceless and repressed.

Protesters gather at a road blockade.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

Due to the geographical nature of Panajachel and the nearby towns, the effects of the roadblocks have hit much faster as supplies such as food, basic commodities, petrol, and even cash has quickly diminished. In a country which does not have potable water, the supply of large, purified water bottles is absolutely vital.

The lack of new fresh fruit and vegetables entering the town, coupled with the loss of income, has forced market traders to increase their prices, sometimes threefold, and beyond the means of local people. Businesses have been allowed to open but only for 2-3 hours from six in the morning; during this time long lines have formed outside of the market and some supermarkets.

People here rely on LPG gas cylinders for their cooking, and again the short supply and the lack of ability to transport them has left many stranded. As the cash machines ran dry, supermarkets became the only option to purchase goods for those lucky enough to have money in the bank, and access to a bank card.

Hardship is nothing new to Guatemalans, and, in the eyes of the vast majority, the fight for democracy is worth the struggle.

On the first day of the protests the entire town was left without electricity until 7 pm. It remains unconfirmed whether the electricity was turned off on purpose as a warning to activists and protesters, or simply if the engineers were not able to pass through the roadblocks to make their repairs.

Reports by the Director of Civil Aeronautics confirmed on Monday that the country’s only international airport La Aurora has ran out of fuel and is no longer able to supply the aircraft arriving at the airport, an issue which has since been resolved with the help of El Salvador.

Most Guatemalans will now be suffering the effects of these demonstrations either through the inability to work, the rising costs of goods, dwindling cash, and eventually hunger. Despite this, the people in the streets and the dedicated activists at the roadblocks are jovial; there are friendly exchanges, smiles, and a real feeling of hope. Hardship is nothing new to Guatemalans, and, in the eyes of the vast majority, the fight for democracy is worth the struggle.

Protesters march down a street with drums.

(Photo: Rachael Mellor/CC BY-ND 4.0)

As of October 8, there are 68 official road blockages on major transport routes throughout the country created and enforced by everyday citizens. This number is growing daily, and most likely official numbers underestimate the true extent as many smaller rural road blocks have not been listed. Tens of thousands of Guatemalans have been protesting peacefully for days without respite. Imagine a nationwide sit-in. Not even the heavy rains have managed to deter spirits. The protests have taken the form of marches and the gathering of large crowds at main transport arteries. Canopies have been set up to provide shelter for the protesters who have brought BBQs, food, speakers, and microphones. Even musicians have joined in and performed through the night to keep moods high.

Guatemalans are famed for their incredible resilience, strength, and determination. They will not stop until Porras and the other prosecutors have stepped down. This is how desperate the people are for change.

Officials have released a statement declaring that all attempts to block transit routes are illegal, and that force will be used if necessary to clear the roads. So far there has been no such escalation, despite an order for the government to enforce this ruling. The government has explicitly refused to call for a state of emergency.

Loss of income, hunger, or any other implications are merely slight inconveniences for Guatemalans who are sadly used to having to stand up for their own rights.

Panajachel is home to a large community of foreigners who have shown their solidarity with local people by either joining the marches, sharing knowledge on social media community groups, donating food and supplies to protesters, or simply respecting the will of the Guatemalan people. It is important for foreigners to share their experiences to give this situation the international attention it deserves, in what has largely been ignored by western media.

Of note, officials have warned that if foreigners become involved in protests or at roadblocks, they risk deportation or being denied entry to the country in the future. So far there has been no evidence of this, and local police in Panajachel offered their assistance to marchers over the weekend, who were a mix of local and international supporters. That said, due diligence should be used at all times for everyone looking to show their solidarity.

Guatemalans are seizing this opportunity to fight for real change. Loss of income, hunger, or any other implications are merely slight inconveniences for Guatemalans who are sadly used to having to stand up for their own rights.

The Organisation of American States on Saturday named the representatives who will mediate between protesters and officials with the aim of achieving an orderly transfer of power. That said, escalations of violence to remove protesters from the streets is expected to commence on Monday.

This piece was originally published in Better World Info.