SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

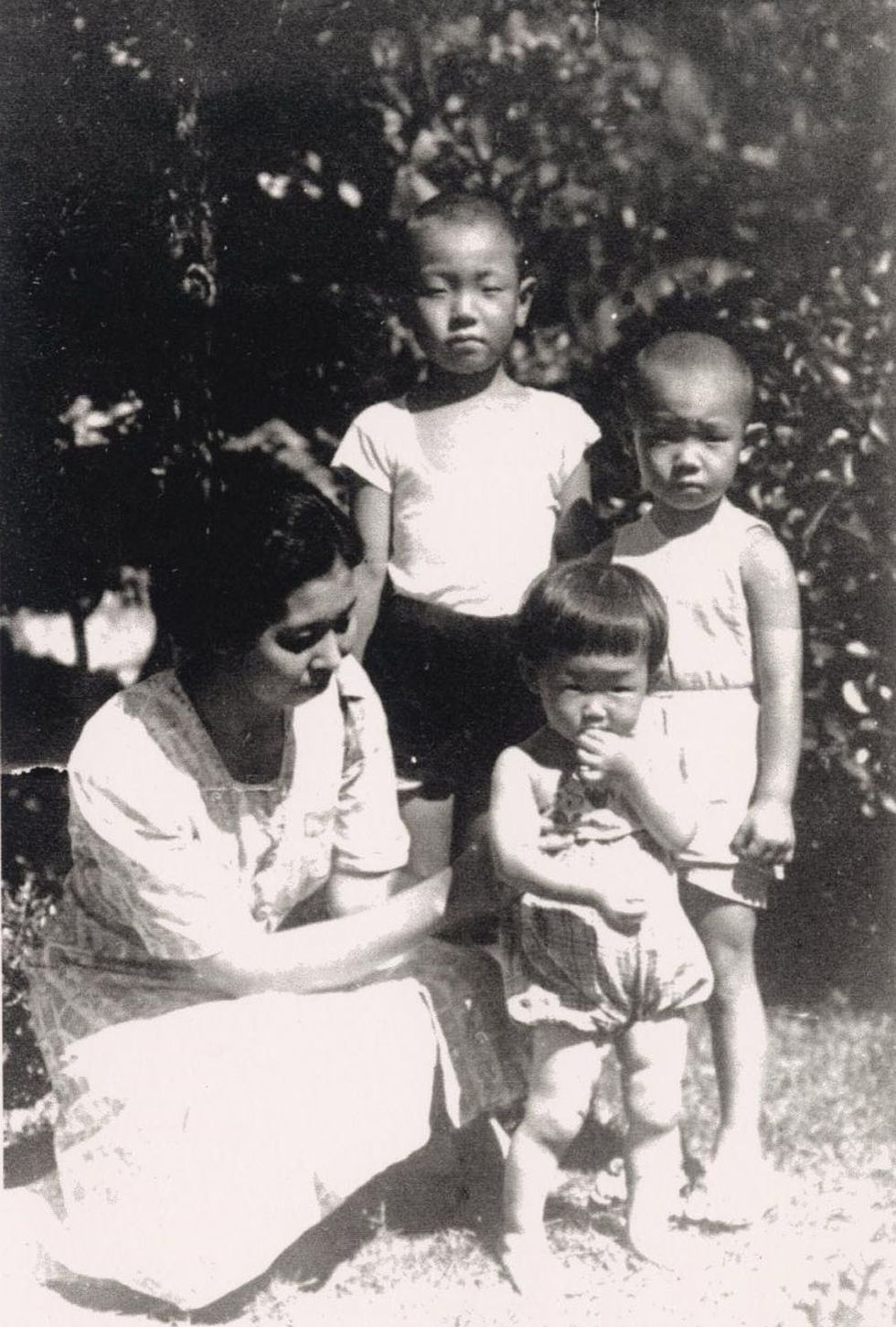

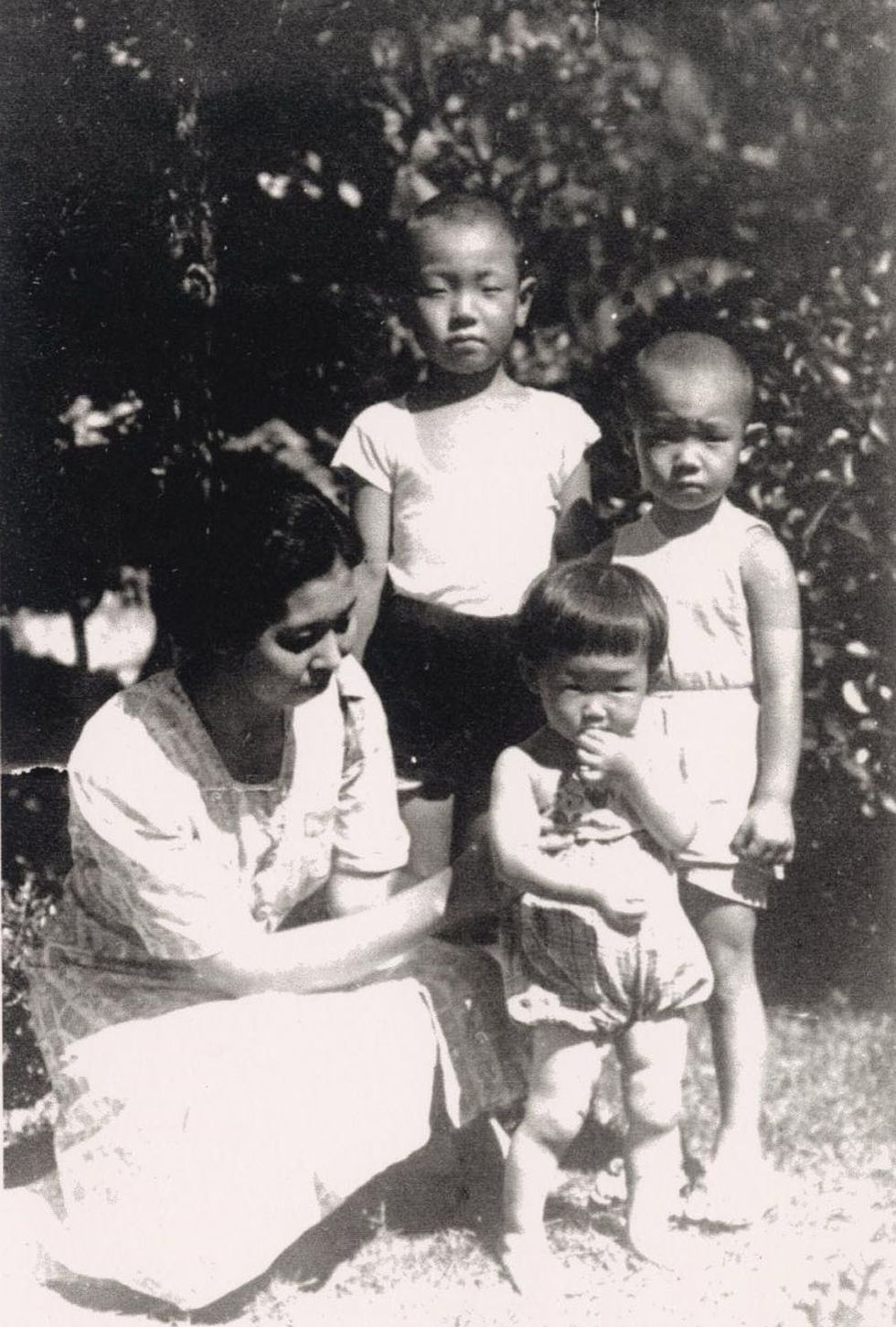

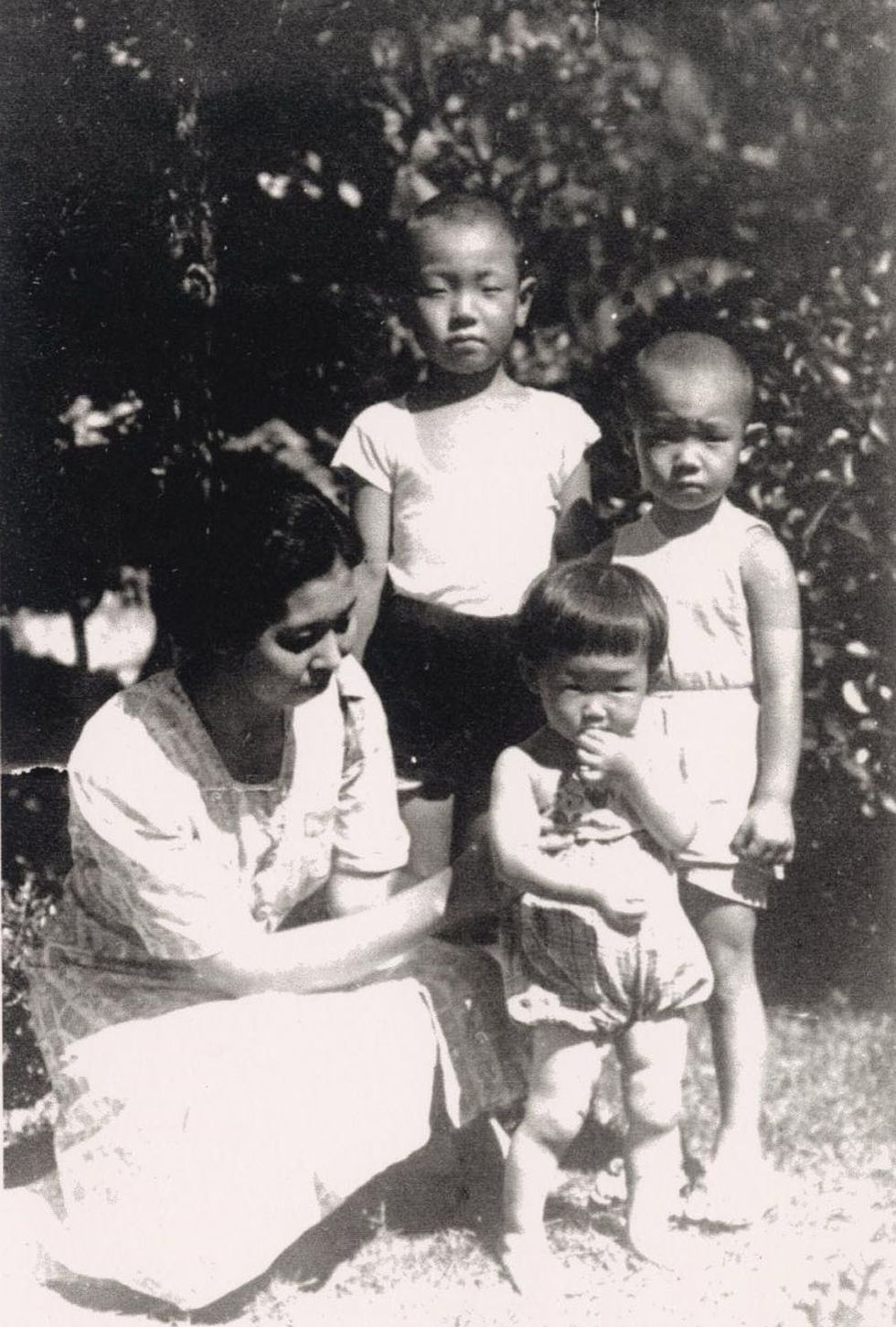

Suzuki Kimiko (left) and her elder brother, Hideaki (right), in Hiroshima a few years before the bombing. Both were killed, along with two other siblings. Their father, Rokuro, was a keen photographer.

The fact that children would suffer the greatest harm of all in the event of a nuclear attack against a city today should have profound implications for policy-making in nuclear-armed states and spur action for disarmament. And yet the world's nuclear-armed states continue to withhold their support for abolition.

Before dawn on August 6, 1945, Tsuyako Kubota gave birth to her second daughter at her home in Hiroshima’s Nishikanon neighborhood. A few hours later, in a blinding flash, much of the city was reduced to smoldering ruins by a single atomic bomb.

The young mother, her newborn baby and her two-year-old daughter, Sumie, became trapped in the wreckage of their home. The girls’ father, Minoru, a Japanese-American from Hawaii, tried desperately to free them.

“Sumie was crying,” he recalled. “She said to me, ‘Daddy, it’s hot! The fire is coming! My hands are burning!’ There was a final scream, and then I couldn’t hear her voice anymore.”

Sumie and her hours-old sister—who was never given a name—were among the estimated 23,000 children killed in the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima 80 years ago this week. A further 15,000 perished in the attack on Nagasaki three days later.

“She said to me, ‘Daddy, it’s hot! The fire is coming! My hands are burning!’ There was a final scream, and then I couldn’t hear her voice anymore.”

Their deaths, and those of tens of thousands of other civilians, challenge official narratives in the West that the use of nuclear weapons against the two Japanese cities in the final days of World War II was morally justified.

A new poll by the Pew Research Center shows that U.S. public support for the attacks is declining. In 1945, it was as high as 85 percent. Today, only around 35 percent of Americans believe their government’s actions were justified, with 31 percent believing they weren’t. The other third are unsure.

…

With few exceptions, those who survived the atomic bombings and are still alive were children at the time. Through their young eyes, they witnessed unimaginable horror. Known in Japanese as hibakusha, many have devoted their lives to the cause of nuclear disarmament, sharing their first-hand testimonies time and again in the hope of avoiding a recurrence of such tragedies. Their warning is stark: humanity and nuclear weapons cannot coexist.

Last December, their efforts were recognized with the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Nihon Hidankyo, or the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations.

Their warning is stark: humanity and nuclear weapons cannot coexist.

Many of the survivors lost their parents, siblings, and friends. They have suffered lifelong physical and psychological trauma. Some have endured multiple surgeries to treat painful keloid scars, extract glass fragments embedded deep in their bodies, or remove cancers caused by their exposure to the bombs’ radiation.

In a nuclear attack, children are especially vulnerable, as their skin is more delicate and their bodies frailer, and they have more cells that are growing and dividing rapidly and thus more susceptible to radiation effects. They are significantly more likely than adults to die from burns, blast injuries, and acute radiation sickness.

As the late paediatric endocrinologist Michael S. Kappy explained in a 1984 paper, “Children and adults do not share equally the dreadful short-term effects of ‘the bomb’, and it is clear from all available data that children are also most susceptible to the long-term effects that appear after varying latency periods.”

The disproportionate impact of nuclear weapons on infants and children was underscored in a declaration adopted this March by the 73 countries that have so far ratified or acceded to the landmark 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

In a nuclear attack, children are especially vulnerable, as their skin is more delicate and their bodies frailer, and they have more cells that are growing and dividing rapidly and thus more susceptible to radiation effects.

The fact that children would suffer the greatest harm of all in the event of a nuclear attack against a city today should have profound implications for policy-making in nuclear-armed states and spur action for disarmament. Yet, all nine such states continue to act contrary to that objective. And the risk of a nuclear weapon being used again appears to be at an all-time high.

…

In Hiroshima, thousands of school students were outdoors creating firebreaks on the morning of the atomic bombing. Completely unshielded from the bomb’s effects, they stood little chance of survival. The mortality rate for those within one kilometre of the hypocentre was around 94 percent. Approximately 6,300 of them died.

Many parents spent days or weeks searching for their missing children in the aftermath. For some, not knowing their children’s fate became unbearable. One mother in Hiroshima, refusing to accept her daughter’s death, kept a door or window open for the rest of her life in case she one day returned home.

Some parents managed to identify the charred, swollen bodies of their children among scores of corpses only by the name tags on their clothes. Others found their children alive and nursed them for days, weeks or months until they took their final breaths. More than a few expressed guilt at the inadequacy of their care amid extreme shortages of medicines and food.

In Nagasaki, one mother watched as four of her children succumbed to acute radiation poisoning one after another. “I kept thinking that human beings shouldn’t die so easily,” she reflected.

Another Nagasaki mother’s face was so badly burnt and disfigured in the attack that her grievously injured two-year-old son couldn’t recognize her as she cared for him in his dying moments.

Some children appeared unharmed at first, having sustained no burns or other visible injuries, but developed fatal diseases years later, as ionizing radiation had entered their bodies and altered their cells.

One such child was Sadako Sasaki, a toddler at the time of the Hiroshima bombing. She died a decade later from acute malignant lymph gland leukemia. During her hospitalization, she folded over a thousand paper cranes with her weak and skinny arms in the hope it would bring her good health.

“Until her very last moment, she held onto her wish and made a great effort to survive,” her father remembered. “I loved her so much that I couldn’t come to terms with her death for a long time.”

Sadako’s tragic story continues to inspire children in Japan and throughout the world to work for the abolition of nuclear weapons—an increasingly urgent task given deteriorating relations among nuclear-armed states and the enhancement and expansion of their arsenals.

It is estimated there are more than 12,000 nuclear weapons in the world today, most of them vastly more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped eight decades ago. In the words of the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, “They offer no security—just carnage and chaos. Their elimination would be the greatest gift we could bestow on future generations.”

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Before dawn on August 6, 1945, Tsuyako Kubota gave birth to her second daughter at her home in Hiroshima’s Nishikanon neighborhood. A few hours later, in a blinding flash, much of the city was reduced to smoldering ruins by a single atomic bomb.

The young mother, her newborn baby and her two-year-old daughter, Sumie, became trapped in the wreckage of their home. The girls’ father, Minoru, a Japanese-American from Hawaii, tried desperately to free them.

“Sumie was crying,” he recalled. “She said to me, ‘Daddy, it’s hot! The fire is coming! My hands are burning!’ There was a final scream, and then I couldn’t hear her voice anymore.”

Sumie and her hours-old sister—who was never given a name—were among the estimated 23,000 children killed in the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima 80 years ago this week. A further 15,000 perished in the attack on Nagasaki three days later.

“She said to me, ‘Daddy, it’s hot! The fire is coming! My hands are burning!’ There was a final scream, and then I couldn’t hear her voice anymore.”

Their deaths, and those of tens of thousands of other civilians, challenge official narratives in the West that the use of nuclear weapons against the two Japanese cities in the final days of World War II was morally justified.

A new poll by the Pew Research Center shows that U.S. public support for the attacks is declining. In 1945, it was as high as 85 percent. Today, only around 35 percent of Americans believe their government’s actions were justified, with 31 percent believing they weren’t. The other third are unsure.

…

With few exceptions, those who survived the atomic bombings and are still alive were children at the time. Through their young eyes, they witnessed unimaginable horror. Known in Japanese as hibakusha, many have devoted their lives to the cause of nuclear disarmament, sharing their first-hand testimonies time and again in the hope of avoiding a recurrence of such tragedies. Their warning is stark: humanity and nuclear weapons cannot coexist.

Last December, their efforts were recognized with the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Nihon Hidankyo, or the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations.

Their warning is stark: humanity and nuclear weapons cannot coexist.

Many of the survivors lost their parents, siblings, and friends. They have suffered lifelong physical and psychological trauma. Some have endured multiple surgeries to treat painful keloid scars, extract glass fragments embedded deep in their bodies, or remove cancers caused by their exposure to the bombs’ radiation.

In a nuclear attack, children are especially vulnerable, as their skin is more delicate and their bodies frailer, and they have more cells that are growing and dividing rapidly and thus more susceptible to radiation effects. They are significantly more likely than adults to die from burns, blast injuries, and acute radiation sickness.

As the late paediatric endocrinologist Michael S. Kappy explained in a 1984 paper, “Children and adults do not share equally the dreadful short-term effects of ‘the bomb’, and it is clear from all available data that children are also most susceptible to the long-term effects that appear after varying latency periods.”

The disproportionate impact of nuclear weapons on infants and children was underscored in a declaration adopted this March by the 73 countries that have so far ratified or acceded to the landmark 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

In a nuclear attack, children are especially vulnerable, as their skin is more delicate and their bodies frailer, and they have more cells that are growing and dividing rapidly and thus more susceptible to radiation effects.

The fact that children would suffer the greatest harm of all in the event of a nuclear attack against a city today should have profound implications for policy-making in nuclear-armed states and spur action for disarmament. Yet, all nine such states continue to act contrary to that objective. And the risk of a nuclear weapon being used again appears to be at an all-time high.

…

In Hiroshima, thousands of school students were outdoors creating firebreaks on the morning of the atomic bombing. Completely unshielded from the bomb’s effects, they stood little chance of survival. The mortality rate for those within one kilometre of the hypocentre was around 94 percent. Approximately 6,300 of them died.

Many parents spent days or weeks searching for their missing children in the aftermath. For some, not knowing their children’s fate became unbearable. One mother in Hiroshima, refusing to accept her daughter’s death, kept a door or window open for the rest of her life in case she one day returned home.

Some parents managed to identify the charred, swollen bodies of their children among scores of corpses only by the name tags on their clothes. Others found their children alive and nursed them for days, weeks or months until they took their final breaths. More than a few expressed guilt at the inadequacy of their care amid extreme shortages of medicines and food.

In Nagasaki, one mother watched as four of her children succumbed to acute radiation poisoning one after another. “I kept thinking that human beings shouldn’t die so easily,” she reflected.

Another Nagasaki mother’s face was so badly burnt and disfigured in the attack that her grievously injured two-year-old son couldn’t recognize her as she cared for him in his dying moments.

Some children appeared unharmed at first, having sustained no burns or other visible injuries, but developed fatal diseases years later, as ionizing radiation had entered their bodies and altered their cells.

One such child was Sadako Sasaki, a toddler at the time of the Hiroshima bombing. She died a decade later from acute malignant lymph gland leukemia. During her hospitalization, she folded over a thousand paper cranes with her weak and skinny arms in the hope it would bring her good health.

“Until her very last moment, she held onto her wish and made a great effort to survive,” her father remembered. “I loved her so much that I couldn’t come to terms with her death for a long time.”

Sadako’s tragic story continues to inspire children in Japan and throughout the world to work for the abolition of nuclear weapons—an increasingly urgent task given deteriorating relations among nuclear-armed states and the enhancement and expansion of their arsenals.

It is estimated there are more than 12,000 nuclear weapons in the world today, most of them vastly more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped eight decades ago. In the words of the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, “They offer no security—just carnage and chaos. Their elimination would be the greatest gift we could bestow on future generations.”

Before dawn on August 6, 1945, Tsuyako Kubota gave birth to her second daughter at her home in Hiroshima’s Nishikanon neighborhood. A few hours later, in a blinding flash, much of the city was reduced to smoldering ruins by a single atomic bomb.

The young mother, her newborn baby and her two-year-old daughter, Sumie, became trapped in the wreckage of their home. The girls’ father, Minoru, a Japanese-American from Hawaii, tried desperately to free them.

“Sumie was crying,” he recalled. “She said to me, ‘Daddy, it’s hot! The fire is coming! My hands are burning!’ There was a final scream, and then I couldn’t hear her voice anymore.”

Sumie and her hours-old sister—who was never given a name—were among the estimated 23,000 children killed in the U.S. atomic bombing of Hiroshima 80 years ago this week. A further 15,000 perished in the attack on Nagasaki three days later.

“She said to me, ‘Daddy, it’s hot! The fire is coming! My hands are burning!’ There was a final scream, and then I couldn’t hear her voice anymore.”

Their deaths, and those of tens of thousands of other civilians, challenge official narratives in the West that the use of nuclear weapons against the two Japanese cities in the final days of World War II was morally justified.

A new poll by the Pew Research Center shows that U.S. public support for the attacks is declining. In 1945, it was as high as 85 percent. Today, only around 35 percent of Americans believe their government’s actions were justified, with 31 percent believing they weren’t. The other third are unsure.

…

With few exceptions, those who survived the atomic bombings and are still alive were children at the time. Through their young eyes, they witnessed unimaginable horror. Known in Japanese as hibakusha, many have devoted their lives to the cause of nuclear disarmament, sharing their first-hand testimonies time and again in the hope of avoiding a recurrence of such tragedies. Their warning is stark: humanity and nuclear weapons cannot coexist.

Last December, their efforts were recognized with the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to Nihon Hidankyo, or the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations.

Their warning is stark: humanity and nuclear weapons cannot coexist.

Many of the survivors lost their parents, siblings, and friends. They have suffered lifelong physical and psychological trauma. Some have endured multiple surgeries to treat painful keloid scars, extract glass fragments embedded deep in their bodies, or remove cancers caused by their exposure to the bombs’ radiation.

In a nuclear attack, children are especially vulnerable, as their skin is more delicate and their bodies frailer, and they have more cells that are growing and dividing rapidly and thus more susceptible to radiation effects. They are significantly more likely than adults to die from burns, blast injuries, and acute radiation sickness.

As the late paediatric endocrinologist Michael S. Kappy explained in a 1984 paper, “Children and adults do not share equally the dreadful short-term effects of ‘the bomb’, and it is clear from all available data that children are also most susceptible to the long-term effects that appear after varying latency periods.”

The disproportionate impact of nuclear weapons on infants and children was underscored in a declaration adopted this March by the 73 countries that have so far ratified or acceded to the landmark 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

In a nuclear attack, children are especially vulnerable, as their skin is more delicate and their bodies frailer, and they have more cells that are growing and dividing rapidly and thus more susceptible to radiation effects.

The fact that children would suffer the greatest harm of all in the event of a nuclear attack against a city today should have profound implications for policy-making in nuclear-armed states and spur action for disarmament. Yet, all nine such states continue to act contrary to that objective. And the risk of a nuclear weapon being used again appears to be at an all-time high.

…

In Hiroshima, thousands of school students were outdoors creating firebreaks on the morning of the atomic bombing. Completely unshielded from the bomb’s effects, they stood little chance of survival. The mortality rate for those within one kilometre of the hypocentre was around 94 percent. Approximately 6,300 of them died.

Many parents spent days or weeks searching for their missing children in the aftermath. For some, not knowing their children’s fate became unbearable. One mother in Hiroshima, refusing to accept her daughter’s death, kept a door or window open for the rest of her life in case she one day returned home.

Some parents managed to identify the charred, swollen bodies of their children among scores of corpses only by the name tags on their clothes. Others found their children alive and nursed them for days, weeks or months until they took their final breaths. More than a few expressed guilt at the inadequacy of their care amid extreme shortages of medicines and food.

In Nagasaki, one mother watched as four of her children succumbed to acute radiation poisoning one after another. “I kept thinking that human beings shouldn’t die so easily,” she reflected.

Another Nagasaki mother’s face was so badly burnt and disfigured in the attack that her grievously injured two-year-old son couldn’t recognize her as she cared for him in his dying moments.

Some children appeared unharmed at first, having sustained no burns or other visible injuries, but developed fatal diseases years later, as ionizing radiation had entered their bodies and altered their cells.

One such child was Sadako Sasaki, a toddler at the time of the Hiroshima bombing. She died a decade later from acute malignant lymph gland leukemia. During her hospitalization, she folded over a thousand paper cranes with her weak and skinny arms in the hope it would bring her good health.

“Until her very last moment, she held onto her wish and made a great effort to survive,” her father remembered. “I loved her so much that I couldn’t come to terms with her death for a long time.”

Sadako’s tragic story continues to inspire children in Japan and throughout the world to work for the abolition of nuclear weapons—an increasingly urgent task given deteriorating relations among nuclear-armed states and the enhancement and expansion of their arsenals.

It is estimated there are more than 12,000 nuclear weapons in the world today, most of them vastly more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped eight decades ago. In the words of the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, “They offer no security—just carnage and chaos. Their elimination would be the greatest gift we could bestow on future generations.”