April, 06 2012, 02:31pm EDT

For Immediate Release

Contact:

Michelle Bazie,202-408-1080,bazie@cbpp.org

Statement: Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the March Employment Report

WASHINGTON

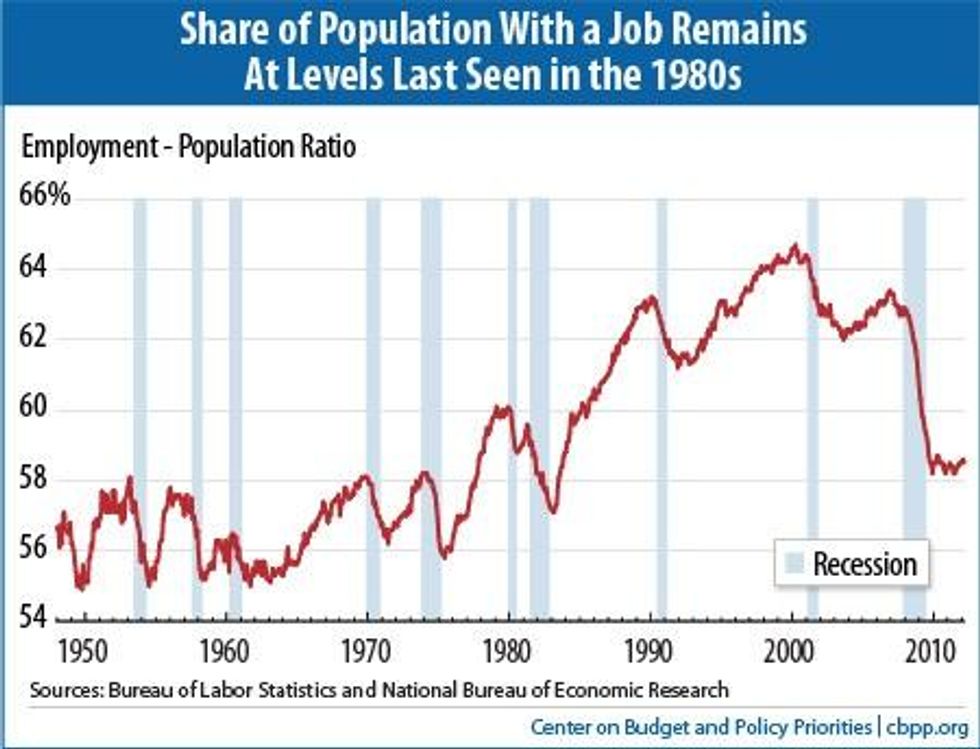

Today's jobs report disappointed expectations, with employers adding only 120,000 jobs in March, making clear that a strong jobs recovery remains elusive. The unemployment rate dipped to 8.2 percent, but that decline reflected people leaving the labor force, not finding jobs. The combination of high unemployment and depressed labor force participation leaves the share of Americans with a job at levels last seen in the mid-1980s (see chart). Though the economy could use a boost through monetary or fiscal policy, that's not likely to occur, further dampening hopes of strong job growth any time soon.

Analysts had expected the stronger job growth of recent months to continue into March and for people to continue returning to the labor force because they sensed improving job prospects. Instead, job growth fell to a level barely sufficient to keep up with population growth and the labor force shrank largely because some of the unemployed stopped looking for jobs and left the labor force entirely.

In a strong jobs recovery, we would expect to see the economy create 250,000 to 300,000 jobs a month or more, together with an increase in labor force participation. Ironically, had we seen a stronger jobs report, we might well not have seen the unemployment rate fall.

When employers first begin to add jobs at a strong rate, people who were not looking for work because job prospects seemed so dismal should start returning to the labor force. Not all of them will find jobs immediately and they will be counted as unemployed until they find jobs. But instead of accelerating, the jobs recovery fell backward and a dip in the unemployment rate associated with a shrinking labor force is nothing to cheer about.

Unfortunately, most private forecasters, the Congressional Budget Office, and the Federal Reserve expect relatively modest growth for the rest of the year and no significant fall in unemployment. The economy surely could use some fuel injection from either monetary policy, fiscal policy, or both, but that's not in the cards -- and that's a bad sign for job growth and for boosting people's confidence that they can find a job.

About the March Jobs Report

Job growth was disappointing in March and a strong jobs recovery remains elusive.

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by 120,000 jobs in March. Private employers added 121,000 jobs. Modest losses in local government jobs and state jobs outside of education were partly offset by modest gains in state education jobs. Overall, the drag from state and government job losses, which has been significant for the past few years, was minimal in March.

- This is the 25th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 4.1 million jobs (a pace of 162,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 3.6 million jobs over the same period, or 143,000 a month. The loss of 474,000 government jobs over this period was dominated by a loss of 348,000 local government jobs.

- Despite the 25 months of private-sector job growth, there were still 5.2 million fewer jobs on nonfarm payrolls in March than when the recession began in December 2007 and 4.8 million fewer jobs on private payrolls. Payroll job growth in March was a disappointing step backward from the pace of job creation in recent months, and we remain well short of the sustained growth of 200,000 to 300,000 jobs or more that is typical of a robust jobs recovery.

- The unemployment rate edged down to 8.2 percent in March, and the number of unemployed Americans dropped slightly to 12.7 million. The unemployment rate was 7.3 percent for whites (2.9 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 14.0 percent for African Americans (5.0 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 10.3 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (4.0 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession and lack of job opportunities drove many people out of the labor force, and we have yet to see a sustained return to labor force participation (people aged 16 and over working or actively looking for work) that would mark a strong jobs recovery. The decline in the labor force in March was discouraging. The number of people with a job fell by 31,000 and the number of people looking for a job fell by 133,000, for a total decline in the labor force of 164,000 people. The labor force participation rate edged down to 63.8 percent. Except for January's 63.7 percent, however, that's its lowest level since 1983.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and has been below 60 percent since early 2009, edged down to 58.5 percent in March.

- Finding a job remains very difficult. The Labor Department's most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure -- which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking and people working part time because they can't find full-time jobs -- was 14.5 percent in March, down from its all-time high of 17.4 percent in October 2009 in data that go back to 1994, but still 5.7 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, almost 23 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Over two-fifths (42.5 percent) of the 12.7 million people who are unemployed -- 5.3 million people -- have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 3.4 percent of the labor force. Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is one of the nation's premier policy organizations working at the federal and state levels on fiscal policy and public programs that affect low- and moderate-income families and individuals.

LATEST NEWS

Trump Regulators Ripped for 'Rushed' Approval of Bill Gates' Nuclear Reactor in Wyoming

"Make no mistake, this type of reactor has major safety flaws compared to conventional nuclear reactors that comprise the operating fleet," said one expert.

Dec 03, 2025

A leading nuclear safety expert sounded the alarm Tuesday over the Trump administration's expedited safety review of an experimental nuclear reactor in Wyoming designed by a company co-founded by tech billionaire Bill Gates and derided as a "Cowboy Chernobyl."

On Monday, the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) announced that it has "completed its final safety evaluation" for Power Station Unit 1 of TerraPower's Natrium reactor in Kemmerer, Wyoming, adding that it found "no safety aspects that would preclude issuing the construction permit."

Co-founded by Microsoft's Gates, TerraPower received a 50-50 cost-share grant for up to $2 billion from the US Department of Energy’s Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program. The 345-megawatt sodium-cooled small modular reactor (SMR) relies upon so-called passive safety features that experts argue could potentially make nuclear accidents worse.

However, federal regulators "are loosening safety and security requirements for SMRs in ways which could cancel out any safety benefits from passive features," according to Union of Concerned Scientists nuclear power safety director Edwin Lyman.

"The only way they could pull this off is by sweeping difficult safety issues under the rug."

The reactor’s construction permit application—which was submitted in March 2024—was originally scheduled for August 2026 completion but was expedited amid political pressure from the Trump administration and Congress in order to comply with an 18-month timeline established in President Donald Trump’s Executive Order 14300.

“The NRC’s rush to complete the Kemmerer plant’s safety evaluation to meet the recklessly abbreviated schedule dictated by President Trump represents a complete abandonment of its obligation to protect public health, safety, and the environment from catastrophic nuclear power plant accidents or terrorist attacks," Lyman said in a statement Tuesday.

Lyman continued:

The only way the staff could finish its review on such a short timeline is by sweeping serious unresolved safety issues under the rug or deferring consideration of them until TerraPower applies for an operating license, at which point it may be too late to correct any problems. Make no mistake, this type of reactor has major safety flaws compared to conventional nuclear reactors that comprise the operating fleet. Its liquid sodium coolant can catch fire, and the reactor has inherent instabilities that could lead to a rapid and uncontrolled increase in power, causing damage to the reactor’s hot and highly radioactive nuclear fuel.

Of particular concern, NRC staff has assented to a design that lacks a physical containment structure to reduce the release of radioactive materials into the environment if a core melt occurs. TerraPower argues that the reactor has a so-called "functional" containment that eliminates the need for a real containment structure. But the NRC staff plainly states that it "did not come to a final determination of the adequacy and acceptability of functional containment performance due to the preliminary nature of the design and analysis."

"Even if the NRC determines later that the functional containment is inadequate, it would be utterly impractical to retrofit the design and build a physical containment after construction has begun," Lyman added. "The potential for rapid power excursions and the lack of a real containment make the Kemmerer plant a true ‘Cowboy Chernobyl.’”

The proposed reactor still faces additional hurdles before construction can begin, including a final environmental impact assessment. However, given the Trump administration's dramatic regulatory rollback, approval and construction are highly likely.

Former NRC officials have voiced alarm over the Trump administration's tightened control over the agency, which include compelling it to send proposed reactor safety rules to the White House for review and possible editing.

Allison Macfarlane, who was nominated to head the NRC during the Obama administration, said earlier this year that Trump's approach marks “the end of independence of the agency.”

“If you aren’t independent of political and industry influence, then you are at risk of an accident,” she warned.

Keep ReadingShow Less

Report Shows How Recycling Is Largely a 'Toxic Lie' Pushed by Plastics Industry

"These corporations and their partners continue to sell the public a comforting lie to hide the hard truth: that we simply have to stop producing so much plastic," said one campaigner.

Dec 03, 2025

A report published Wednesday by Greenpeace exposes the plastics industry as "merchants of myth" still peddling the false promise of recycling as a solution to the global pollution crisis, even as the vast bulk of commonly produced plastics remain unrecyclable.

"After decades of meager investments accompanied by misleading claims and a very well-funded industry public relations campaign aimed at persuading people that recycling can make plastic use sustainable, plastic recycling remains a failed enterprise that is economically and technically unviable and environmentally unjustifiable," the report begins.

"The latest US government data indicates that just 5% of US plastic waste is recycled annually, down from a high of 9.5% in 2014," the publication continues. "Meanwhile, the amount of single-use plastics produced every year continues to grow, driving the generation of ever greater amounts of plastic waste and pollution."

Among the report's findings:

- Only a fifth of the 8.8 million tons of the most commonly produced types of plastics—found in items like bottles, jugs, food containers, and caps—are actually recyclable;

- Major brands like Coca-Cola, Unilever, and Nestlé have been quietly retracting sustainability commitments while continuing to rely on single-use plastic packaging; and

- The US plastic industry is undermining meaningful plastic regulation by making false claims about the recyclability of their products to avoid bans and reduce public backlash.

"Recycling is a toxic lie pushed by the plastics industry that is now being propped up by a pro-plastic narrative emanating from the White House," Greenpeace USA oceans campaign director John Hocevar said in a statement. "These corporations and their partners continue to sell the public a comforting lie to hide the hard truth: that we simply have to stop producing so much plastic."

"Instead of investing in real solutions, they’ve poured billions into public relations campaigns that keep us hooked on single-use plastic while our communities, oceans, and bodies pay the price," he added.

Greenpeace is among the many climate and environmental groups supporting a global plastics treaty, an accord that remains elusive after six rounds of talks due to opposition from the United States, Saudi Arabia, and other nations that produce the petroleum products from which almost all plastics are made.

Honed from decades of funding and promoting dubious research aimed at casting doubts about the climate crisis caused by its products, the petrochemical industry has sent a small army of lobbyists to influence global treaty negotiations.

In addition to environmental and climate harms, plastics—whose chemicals often leach into the food and water people eat and drink—are linked to a wide range of health risks, including infertility, developmental issues, metabolic disorders, and certain cancers.

Plastics also break down into tiny particles found almost everywhere on Earth—including in human bodies—called microplastics, which cause ailments such as inflammation, immune dysfunction, and possibly cardiovascular disease and gut biome imbalance.

A study published earlier this year in the British medical journal The Lancet estimated that plastics are responsible for more than $1.5 trillion in health-related economic losses worldwide annually—impacts that disproportionately affect low-income and at-risk populations.

As Jo Banner, executive director of the Descendants Project—a Louisiana advocacy group dedicated to fighting environmental racism in frontline communities—said in response to the new Greenpeace report, "It’s the same story everywhere: poor, Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities turned into sacrifice zones so oil companies and big brands can keep making money."

"They call it development—but it’s exploitation, plain and simple," Banner added. "There’s nothing acceptable about poisoning our air, water, and food to sell more throwaway plastic. Our communities are not sacrifice zones, and we are not disposable people.”

Writing for Time this week, Judith Enck, a former regional administrator at the US Environmental Protection Agency and current president of the environmental justice group Beyond Plastics, said that "throwing your plastic bottles in the recycling bin may make you feel good about yourself, or ease your guilt about your climate impact. But recycling plastic will not address the plastic pollution crisis—and it is time we stop pretending as such."

"So what can we do?" Enck continued. "First, companies need to stop producing so much plastic and shift to reusable and refillable systems. If reducing packaging or using reusable packaging is not possible, companies should at least shift to paper, cardboard, glass, or metal."

"Companies are not going to do this on their own, which is why policymakers—the officials we elected to protect us—need to require them to do so," she added.

Although lawmakers in the 119th US Congress have introduced a handful of bills aimed at tackling plastic pollution, such proposals are all but sure to fail given Republican control of both the House of Representatives and Senate and the Trump administration's pro-petroleum policies.

Keep ReadingShow Less

Platner 20 Points Ahead of Mills in Maine Senate Race as Critics Spotlight Her Anti-Worker Veto Record

The new poll, said the progressive candidate, “lays clear what our theory is, which is that we are not going to defeat Susan Collins running the same exact kind of playbook that we’ve run in the past."

Dec 03, 2025

It's been more than a month since a media firestorm over old Reddit posts and a tattoo thrust US Senate candidate Graham Platner into the national spotlight, just as Maine Gov. Janet Mills was entering the Democratic primary race in hopes of challenging Republican Sen. Susan Collins—a controversy that did not appear at the time to make a dent in political newcomer Platner's chances in the election.

On Wednesday, the latest polling showed that the progressive combat veteran and oyster farmer has maintained the lead that was reported in a number of surveys just after the national media descended on the New England state to report on his past online comments and a tattoo that some said resembled a Nazi symbol, which he subsequently had covered up.

The Progressive Change Campaign Committee (PCCC), which endorsed Platner on Wednesday, commissioned the new poll, which showed him polling at 58% compared to Mills' 38%.

Nancy Zdunkewicz, a pollster with Z to A Polling, which conducted the survey on behalf of the PCCC, said the poll represented "really impressive early consolidation" for Platner, with the primary election still six months away.

“Platner isn’t just leading in the Democratic primary. He’s leading by a lot, 20 points—58% are supporting him,” Zdunkewicz told Zeteo. “Only 38% are supporting Mills. There are very few undecided voters or weak supporters for Mills to win over at this point in the race."

Platner has consistently spoken to packed rooms across Maine since launching his campaign in August, promoting a platform that is unapologetically focused on delivering affordability and a better quality of life for Mainers.

He supports expanding the popular Medicare program to all Americans; drew raucous applause at an early rally by declaring, “Our taxpayer dollars can build schools and hospitals in America, not bombs to destroy them in Gaza"; and has spoken in support of breaking up tech giants and a federal war crimes investigation into Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth over his deadly boat strikes in the Caribbean.

Mills entered the race after Democratic leaders including Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) urged her to. She garnered national attention earlier this year for standing up to President Donald Trump when he threatened federal funding for Maine over the state's policy of allowing students to play on school athletic teams that correspond with their gender.

But the PCCC survey found that when respondents learned details about each candidate, negative critiques of Mills were more damaging to her than Platner's old Reddit posts and tattoo.

Zdunkewicz disclosed Platner's recent controversy to the voters she surveyed, as well as his statements about how his views have shifted in recent years, and found that 21% of voters were more likely to back him after learning about his background. Thirty-nine percent said they were less likely to support him.

The pollster also talked to respondents about the fact that establishment Democrats pushed Mills, who is 77, to enter the race, and about a number of bills she has vetoed as governor, including a tax on the wealthy, a bill to set up a tracking system for rape kits, two bills to reduce prescription drug costs, and several bills promoting workers' rights.

Only 14% of Mainers said they were more likely to vote for Mills after learning those details, while 50% said they were less likely to support her.

At The Lever, Luke Goldstein on Wednesday reported that Mills' vetoes have left many with the "perception that she’s mostly concerned with business interests," as former Democratic Maine state lawmaker Andy O'Brien said. Corporate interests gave more than $200,000 to Mills' two gubernatorial campaigns.

Earlier this year, Mills struck down a labor-backed bill to allow farm workers to discuss their pay with one another without fear of retaliation. Last year, she blocked a bill to set a minimum wage for farm laborers, opposing a provision that would have allowed workers to sue their employers.

She also vetoed a bill banning noncompete agreements and one that would have banned anti-union tactics by corporations.

"In previous years," Goldstein reported, "she blocked efforts to stop employers from punishing employees who took state-guaranteed paid time off, killed a permitting reform bill to streamline offshore wind developments because it included a provision mandating union jobs, and vetoed a modest labor bill that would have required the state government to merely study the issue of paper mill workers being forced to work overtime without adequate compensation."

Speaking to PCCC supporters on Wednesday, Platner suggested the new polling shows that many Mainers agree with the central argument of his campaign: "We need to build power again for working people, both in Maine and nationally.”

The survey, he said, “lays clear what our theory is, which is that we are not going to defeat Susan Collins running the same exact kind of playbook that we’ve run in the past—which is an establishment politician supported by the power structures, supported by Washington, DC, coming up to Maine and trying to run a kind of standard race... We are really trying to build a grassroots movement up here."

Keep ReadingShow Less

Most Popular