The Sentencing Project on Thursday released a report estimating that 4 million U.S. adults are ineligible to vote in the 2024 election due to felony disenfranchisement, including a disproportionate number of people of color.

The research and advocacy group's 40-page report, Locked Out 2024, finds that 1.7% of adults nationwide are disenfranchised due to felony voting bans, and in certain states—including swing states that could decide the presidential race—that figure is far higher.

Advocates for restoring voting rights to people with felonies argue that disenfranchisement laws are racist and undemocratic.

"Felony disenfranchisement remains a critical barrier to full civic participation, particularly for communities of color," Kara Gotsch, executive director of the Sentencing Project, said in a statement.

"Felony disenfranchisement echoes policies of the past, like poll taxes and literacy tests," she added. "Felony voting bans keep communities that have been historically unheard and under-resourced from having equal representation in our democracy. It's time to guarantee voting rights for all, including those with felony convictions, to create a truly inclusive democracy."

Source: The Sentencing Project

Source: The Sentencing Project

Gotsch noted that there's been progress in many states in recent years, leading to decreased national figures. Felony disenfranchisement peaked in the 2010s; a 2016 report from the Sentencing Project estimated the national figure at 5.9 million. The current 4 million figure represents a 31% decline over 7 years.

Democratic-controlled states have generally instituted more reforms, though some Republican-led states have also done so.

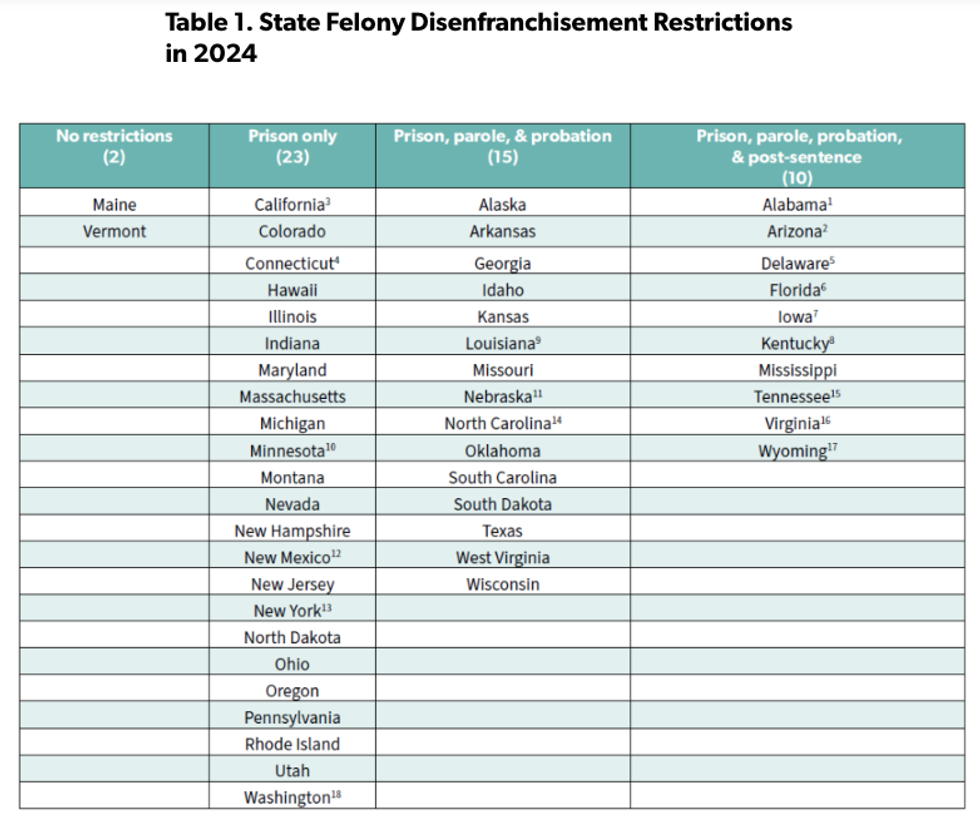

The only states that don't restrict voting while in prison—or at any time thereafter, for convicted felons—are Maine and Vermont; Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C. have the same policy.

Tennessee has the highest percentage of felony disenfranchisement at 7.68% of the adult population.

Florida has the second highest percentage—6.13%—and the highest number of disenfranchised people in absolute terms, at an estimated 961,757, accounting for nearly a quarter of the national total. Florida's Electoral College tally is expected to go to Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump—himself a felon awaiting sentencing—in the election, though the race there remains competitive.

Floridians voted in favor of a referendum to restore voting rights to felons in most cases in 2018, which progressives considered a monumental victory. However, the following year, the Republican-led state Legislature teamed with Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis to weaken the outcome by instituting a law requiring that court fees be paid before reinstatement—they "re-disenfranchised" the majority of those whose rights had been restored, according to the Sentencing Project report. A federal appeals court upheld the Republican law.

Two states that could be even more competitive in next month's presidential election are also deeply affected by felony disenfranchisement. Arizona disenfranchises 4.2% of its adults, while Georgia prevents 3.25% from voting, according to the report.

In each of the four states mentioned, the percentage of Black adults who are disenfranchised is far higher than the overall, cross-racial percentage, as is true at the national level: While 1.7% of U.S. adults are disenfranchised, 4.5% of Black adults are. In Florida, 12.74% of Black people are disenfranchised.

The Sentencing Project and other groups have tackled disenfranchisement as a racial justice issue, pointing out that many of the laws barring felons from voting date to the post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow period.

"The Locked Out 2024 report underscores a harsh reality: Our nation remains ensnared by the remnants of Jim Crow through the practice of felony disenfranchisement," Nicole Porter, the Sentencing Project's advocacy director, said in the statement. "Black and brown communities bear the brunt of felony voting bans, further perpetuating the persistent racial inequities that plague our country."

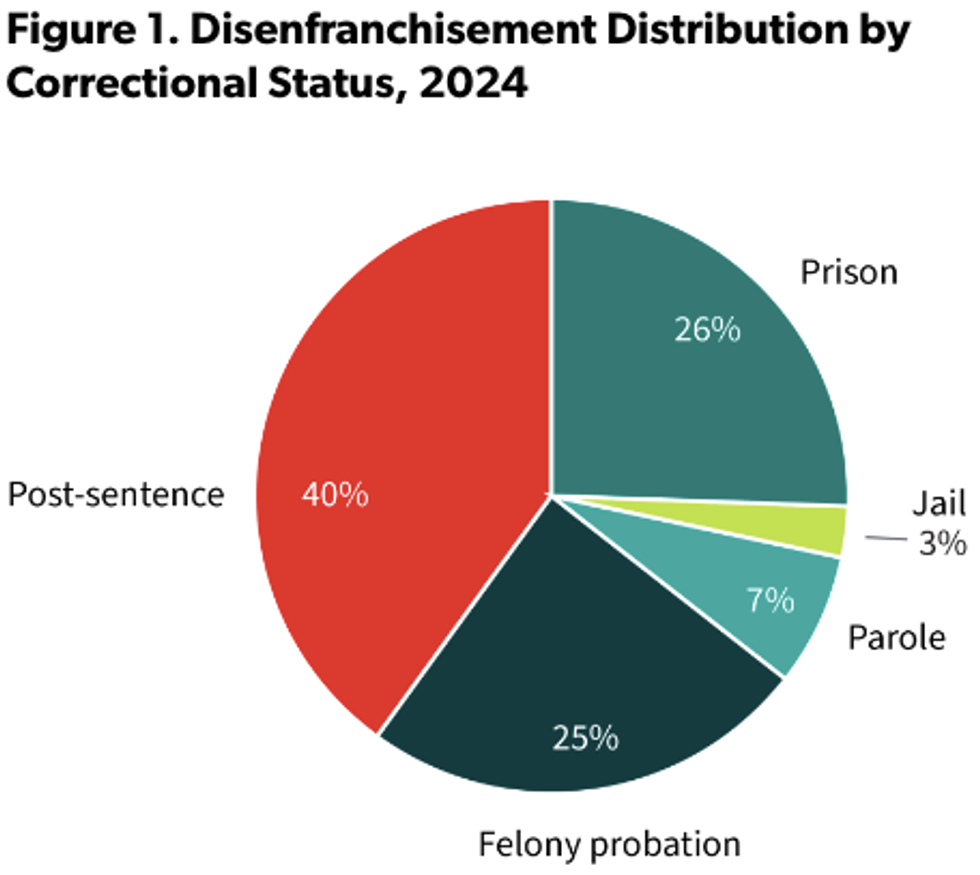

Most of the people who've lost the right to vote due to a felony conviction are no longer in prison or jail. In fact, about 40% have completed their sentencing requirements entirely, the report says.

Source: The Sentencing Project

Source: The Sentencing Project

The report was written by five researchers based at different U.S. universities, most of whom are criminologists. They didn't conduct an exact count of disenfranchised adults but rather used social science methods to estimate the figures. The Sentencing Project has released research of this type every two years since 1998.

The findings don't take into account de facto disenfranchisement "wherein individuals legally allowed to vote do not do so due to legal ambiguity, misinformation regarding voting eligibility, fear of an illegal voting conviction," the report says.

Source: The Sentencing Project

Source: The Sentencing Project  Source: The Sentencing Project

Source: The Sentencing Project