SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

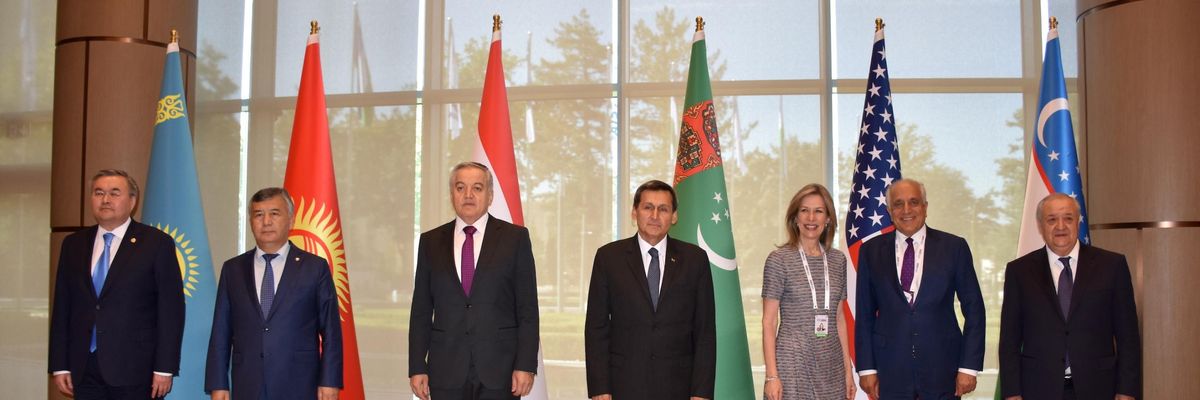

From left to right--Kazakhstan Foreign Minister Mukhtar Tleuberdi, Kyrgyzstan Deputy Foreign Minister Nurlan Niyazaliev, Tajikistan Foreign Minister Sirojiddin Muhriddin, Turkmenistan Vice President Rashit Meredov, U.S. Homeland Security Adviser and Deputy National Security Adviser Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall, U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad, and Uzbekistan Foreign Minister Abdulaziz Kamilov attend the "C5+1" Foreign Ministers of Central Asia and U.S. meeting in Tashkent, Uzbekistan on July 15, 2021. (Photo: Bahtiyar Abdulkerimov/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

As it did while attempting to build a natural gas pipeline through the region in the 1990s and during the early years of the so-called War on Terror, the U.S. government is once again courting Central Asian dictatorships in a bid to secure a military staging area from which it could launch strikes against resurgent Islamist militants in the post-Afghan War era.

The Associated Press reports U.S. diplomats are mounting a "charm offensive" in a bid to woo leaders of nations including Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan into agreeing to provide U.S. military forces with bases close to the Afghan border that could be used for the type of "over-the-horizon" operations that President Joe Biden and Pentagon brass say may continue after the withdrawal, as well as temporary relocation sites for thousands of Afghan translators and other collaborators with the nearly 20-year invasion and occupation of Afghanistan.

While U.S. forces--which are set to leave Afghanistan by the end of August--are perfectly capable of striking targets anywhere in the region from aircraft carriers or bases in the Middle East and Asia, Pentagon planners prefer the advantages of proximity that nearby staging areas would provide.

However, unlike in 2001--when Central Asian governments eagerly cooperated with the George W. Bush administration by allowing U.S. forces to set up bases from which much of the Afghan War was conducted--leaders of those nations are wary of offering the same level of cooperation.

On Wednesday, the White House announced that Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall, Biden's assistant for homeland security, "will lead a U.S. delegation to a high-level international conference promoting prosperity, security, and regional connectivity between Central and South Asia in Tashkent, Uzbekistan."

Sherwood-Randall was accompanied by officials including U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad--a veteran of the Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump administrations.

An Afghan native, Khalilzad played a key role in supporting the mujahideen fighters--who included Osama bin Laden--in their war against the Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s. During the 1990s he was also a director of strategy, doctrine, and force structure at the RAND Corporation and was a member of the pro-imperialist Project for the New American Century (PNAC), which advocated U.S. global dominance (pdf) and regime change in Iraq prior to 9/11.

Khalilzad is also a former liaison between oil company Unocal, now part of Chevron, and the Taliban during the late 1990s when U.S. leaders were courting the extremist group due to a desire to build a natural gas pipeline from Central Asia to the Arabian Sea--even as the fundamentalists' horrific atrocities were shocking the world's conscience.

Securing the pipeline agreement, as well as the wartime military bases and supply route into Afghanistan--known as the Northern Distribution Network--meant maintaining friendly relations with some of the world's most brutal dictatorships, including the regimes of Turkmenistan's "president for life" Saparmurat Niyazov, who built an estimated 10,000 statues of his likeness and renamed the month of January after himself, and Uzbekistan's Islam Karimov, who perpetuated institutionalized agricultural slavery and boiled dissenters alive.

While Niyazov and Karimov are long dead, both nations remain under the rule of oppressive dictators. According to Human Rights Watch, "Turkmenistan remains an isolated and repressive country under the authoritarian rule of President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov and his associates."

"The government brutally punishes all unauthorized forms of religious and political expression," says HRW. "Dozens of forcibly disappeared are presumably held in Turkmen prisons."

As for Uzbekistan, HRW says that since "President Shavkat Mirziyoyev assumed the presidency in 2016, the government has taken some concrete steps to improve the country's human rights record."

"Nevertheless, Uzbekistan's political system remains largely authoritarian," the rights group says. "Many reform promises remain unfulfilled. Thousands of people, mainly peaceful religious believers, remain in prison on false charges. During 2020, there were reports of torture and ill-treatment in prisons, most former prisoners were not rehabilitated, journalists and activists were persecuted, independent rights groups were denied registration, and forced labor was not eliminated."

In Tajikistan, HRW reports that "authorities continued to jail government critics, including opposition activists and journalists, for lengthy prison terms on politically motivated grounds. They also intensified harassment of relatives of peaceful dissidents abroad and continued to forcibly return political opponents from abroad using politically motivated extradition requests."

"The government severely restricts freedom of expression, association, assembly, and religion, including through heavy censorship of the internet," the group says. "Until the end of April, the Tajik government denied the existence of the Covid-19 virus in the country and was late to introduce meaningful measures to slow its spread."

In Kazakhstan, HRW says that "President Kasym-Jomart Tokaev's promises for reform did not bring about meaningful improvements in... human rights record in 2020. Government critics faced harassment and prosecution, and free speech was suppressed, especially in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic."

In Kyrgyzstan "the death in custody of the wrongfully imprisoned human rights defender Azimjon Askarov in July was one of the low points of [the nation's] rights record during the year," says HRW. "Kyrgyzstan held parliamentary elections in October, which international observers found to be competitive but tainted by claims of vote buying."

Nevertheless, the Biden administration, like its predecessors, is keen to work with Central Asian regimes to achieve U.S. strategic objectives, even if regional dictators are less inclined to partner with Washington than they were before.

U.S. State Department spokesperson Ned Price said Wednesday that the Central Asian governments "will make sovereign decisions about their level of the cooperation with the United States" after American troops leave Afghanistan.

Price added that a stable post-U.S. withdrawal Afghanistan is "not only in our interests... it is much more and certainly in the immediate interests of Afghanistan's neighbors."

John Herbst, a former U.S. ambassador to Uzbekistan who was instrumental in securing American access to bases there after 9/11, told the AP that U.S. credibility in Central Asia has "taken a hit through our failures in Afghanistan."

"Is that a mortal hit? Probably not," said Herbst. "But it's still a very powerful factor."

The U.S. is vying with Russia--with which the Central Asian republics were united during the era of the former Soviet Union--China, and, increasingly, the Taliban, which has launched a neighborly charm offensive of its own, for influence in the region.

"Russia has strong historical, cultural, economic, and societal ties with the Central Asian region and is seeking to reassert its influence there, to counter the influence of actors from outside of the region, particularly the U.S.," Tracey German, a specialist in Russian foreign and security policy at the Defense Studies Department at King's College London, told Newsweek. "It views the region as its own strategic backyard."

Earlier this week, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said, "I would emphasize that the redeployment of the American permanent military presence to the countries neighboring Afghanistan is unacceptable."

"We told the Americans in a direct and straightforward way that it would change a lot of things not only in our perceptions of what's going on in that important region, but also in our relations with the United States," he added.

As for the Taliban, it has in recent months been dispatching its own diplomats to regional capitals in a bid to shore up relations with its neighbors. However, Herbst said that "all the countries in the region... have to worry about Taliban intentions."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As it did while attempting to build a natural gas pipeline through the region in the 1990s and during the early years of the so-called War on Terror, the U.S. government is once again courting Central Asian dictatorships in a bid to secure a military staging area from which it could launch strikes against resurgent Islamist militants in the post-Afghan War era.

The Associated Press reports U.S. diplomats are mounting a "charm offensive" in a bid to woo leaders of nations including Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan into agreeing to provide U.S. military forces with bases close to the Afghan border that could be used for the type of "over-the-horizon" operations that President Joe Biden and Pentagon brass say may continue after the withdrawal, as well as temporary relocation sites for thousands of Afghan translators and other collaborators with the nearly 20-year invasion and occupation of Afghanistan.

While U.S. forces--which are set to leave Afghanistan by the end of August--are perfectly capable of striking targets anywhere in the region from aircraft carriers or bases in the Middle East and Asia, Pentagon planners prefer the advantages of proximity that nearby staging areas would provide.

However, unlike in 2001--when Central Asian governments eagerly cooperated with the George W. Bush administration by allowing U.S. forces to set up bases from which much of the Afghan War was conducted--leaders of those nations are wary of offering the same level of cooperation.

On Wednesday, the White House announced that Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall, Biden's assistant for homeland security, "will lead a U.S. delegation to a high-level international conference promoting prosperity, security, and regional connectivity between Central and South Asia in Tashkent, Uzbekistan."

Sherwood-Randall was accompanied by officials including U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad--a veteran of the Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump administrations.

An Afghan native, Khalilzad played a key role in supporting the mujahideen fighters--who included Osama bin Laden--in their war against the Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s. During the 1990s he was also a director of strategy, doctrine, and force structure at the RAND Corporation and was a member of the pro-imperialist Project for the New American Century (PNAC), which advocated U.S. global dominance (pdf) and regime change in Iraq prior to 9/11.

Khalilzad is also a former liaison between oil company Unocal, now part of Chevron, and the Taliban during the late 1990s when U.S. leaders were courting the extremist group due to a desire to build a natural gas pipeline from Central Asia to the Arabian Sea--even as the fundamentalists' horrific atrocities were shocking the world's conscience.

Securing the pipeline agreement, as well as the wartime military bases and supply route into Afghanistan--known as the Northern Distribution Network--meant maintaining friendly relations with some of the world's most brutal dictatorships, including the regimes of Turkmenistan's "president for life" Saparmurat Niyazov, who built an estimated 10,000 statues of his likeness and renamed the month of January after himself, and Uzbekistan's Islam Karimov, who perpetuated institutionalized agricultural slavery and boiled dissenters alive.

While Niyazov and Karimov are long dead, both nations remain under the rule of oppressive dictators. According to Human Rights Watch, "Turkmenistan remains an isolated and repressive country under the authoritarian rule of President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov and his associates."

"The government brutally punishes all unauthorized forms of religious and political expression," says HRW. "Dozens of forcibly disappeared are presumably held in Turkmen prisons."

As for Uzbekistan, HRW says that since "President Shavkat Mirziyoyev assumed the presidency in 2016, the government has taken some concrete steps to improve the country's human rights record."

"Nevertheless, Uzbekistan's political system remains largely authoritarian," the rights group says. "Many reform promises remain unfulfilled. Thousands of people, mainly peaceful religious believers, remain in prison on false charges. During 2020, there were reports of torture and ill-treatment in prisons, most former prisoners were not rehabilitated, journalists and activists were persecuted, independent rights groups were denied registration, and forced labor was not eliminated."

In Tajikistan, HRW reports that "authorities continued to jail government critics, including opposition activists and journalists, for lengthy prison terms on politically motivated grounds. They also intensified harassment of relatives of peaceful dissidents abroad and continued to forcibly return political opponents from abroad using politically motivated extradition requests."

"The government severely restricts freedom of expression, association, assembly, and religion, including through heavy censorship of the internet," the group says. "Until the end of April, the Tajik government denied the existence of the Covid-19 virus in the country and was late to introduce meaningful measures to slow its spread."

In Kazakhstan, HRW says that "President Kasym-Jomart Tokaev's promises for reform did not bring about meaningful improvements in... human rights record in 2020. Government critics faced harassment and prosecution, and free speech was suppressed, especially in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic."

In Kyrgyzstan "the death in custody of the wrongfully imprisoned human rights defender Azimjon Askarov in July was one of the low points of [the nation's] rights record during the year," says HRW. "Kyrgyzstan held parliamentary elections in October, which international observers found to be competitive but tainted by claims of vote buying."

Nevertheless, the Biden administration, like its predecessors, is keen to work with Central Asian regimes to achieve U.S. strategic objectives, even if regional dictators are less inclined to partner with Washington than they were before.

U.S. State Department spokesperson Ned Price said Wednesday that the Central Asian governments "will make sovereign decisions about their level of the cooperation with the United States" after American troops leave Afghanistan.

Price added that a stable post-U.S. withdrawal Afghanistan is "not only in our interests... it is much more and certainly in the immediate interests of Afghanistan's neighbors."

John Herbst, a former U.S. ambassador to Uzbekistan who was instrumental in securing American access to bases there after 9/11, told the AP that U.S. credibility in Central Asia has "taken a hit through our failures in Afghanistan."

"Is that a mortal hit? Probably not," said Herbst. "But it's still a very powerful factor."

The U.S. is vying with Russia--with which the Central Asian republics were united during the era of the former Soviet Union--China, and, increasingly, the Taliban, which has launched a neighborly charm offensive of its own, for influence in the region.

"Russia has strong historical, cultural, economic, and societal ties with the Central Asian region and is seeking to reassert its influence there, to counter the influence of actors from outside of the region, particularly the U.S.," Tracey German, a specialist in Russian foreign and security policy at the Defense Studies Department at King's College London, told Newsweek. "It views the region as its own strategic backyard."

Earlier this week, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said, "I would emphasize that the redeployment of the American permanent military presence to the countries neighboring Afghanistan is unacceptable."

"We told the Americans in a direct and straightforward way that it would change a lot of things not only in our perceptions of what's going on in that important region, but also in our relations with the United States," he added.

As for the Taliban, it has in recent months been dispatching its own diplomats to regional capitals in a bid to shore up relations with its neighbors. However, Herbst said that "all the countries in the region... have to worry about Taliban intentions."

As it did while attempting to build a natural gas pipeline through the region in the 1990s and during the early years of the so-called War on Terror, the U.S. government is once again courting Central Asian dictatorships in a bid to secure a military staging area from which it could launch strikes against resurgent Islamist militants in the post-Afghan War era.

The Associated Press reports U.S. diplomats are mounting a "charm offensive" in a bid to woo leaders of nations including Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan into agreeing to provide U.S. military forces with bases close to the Afghan border that could be used for the type of "over-the-horizon" operations that President Joe Biden and Pentagon brass say may continue after the withdrawal, as well as temporary relocation sites for thousands of Afghan translators and other collaborators with the nearly 20-year invasion and occupation of Afghanistan.

While U.S. forces--which are set to leave Afghanistan by the end of August--are perfectly capable of striking targets anywhere in the region from aircraft carriers or bases in the Middle East and Asia, Pentagon planners prefer the advantages of proximity that nearby staging areas would provide.

However, unlike in 2001--when Central Asian governments eagerly cooperated with the George W. Bush administration by allowing U.S. forces to set up bases from which much of the Afghan War was conducted--leaders of those nations are wary of offering the same level of cooperation.

On Wednesday, the White House announced that Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall, Biden's assistant for homeland security, "will lead a U.S. delegation to a high-level international conference promoting prosperity, security, and regional connectivity between Central and South Asia in Tashkent, Uzbekistan."

Sherwood-Randall was accompanied by officials including U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad--a veteran of the Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump administrations.

An Afghan native, Khalilzad played a key role in supporting the mujahideen fighters--who included Osama bin Laden--in their war against the Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s. During the 1990s he was also a director of strategy, doctrine, and force structure at the RAND Corporation and was a member of the pro-imperialist Project for the New American Century (PNAC), which advocated U.S. global dominance (pdf) and regime change in Iraq prior to 9/11.

Khalilzad is also a former liaison between oil company Unocal, now part of Chevron, and the Taliban during the late 1990s when U.S. leaders were courting the extremist group due to a desire to build a natural gas pipeline from Central Asia to the Arabian Sea--even as the fundamentalists' horrific atrocities were shocking the world's conscience.

Securing the pipeline agreement, as well as the wartime military bases and supply route into Afghanistan--known as the Northern Distribution Network--meant maintaining friendly relations with some of the world's most brutal dictatorships, including the regimes of Turkmenistan's "president for life" Saparmurat Niyazov, who built an estimated 10,000 statues of his likeness and renamed the month of January after himself, and Uzbekistan's Islam Karimov, who perpetuated institutionalized agricultural slavery and boiled dissenters alive.

While Niyazov and Karimov are long dead, both nations remain under the rule of oppressive dictators. According to Human Rights Watch, "Turkmenistan remains an isolated and repressive country under the authoritarian rule of President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov and his associates."

"The government brutally punishes all unauthorized forms of religious and political expression," says HRW. "Dozens of forcibly disappeared are presumably held in Turkmen prisons."

As for Uzbekistan, HRW says that since "President Shavkat Mirziyoyev assumed the presidency in 2016, the government has taken some concrete steps to improve the country's human rights record."

"Nevertheless, Uzbekistan's political system remains largely authoritarian," the rights group says. "Many reform promises remain unfulfilled. Thousands of people, mainly peaceful religious believers, remain in prison on false charges. During 2020, there were reports of torture and ill-treatment in prisons, most former prisoners were not rehabilitated, journalists and activists were persecuted, independent rights groups were denied registration, and forced labor was not eliminated."

In Tajikistan, HRW reports that "authorities continued to jail government critics, including opposition activists and journalists, for lengthy prison terms on politically motivated grounds. They also intensified harassment of relatives of peaceful dissidents abroad and continued to forcibly return political opponents from abroad using politically motivated extradition requests."

"The government severely restricts freedom of expression, association, assembly, and religion, including through heavy censorship of the internet," the group says. "Until the end of April, the Tajik government denied the existence of the Covid-19 virus in the country and was late to introduce meaningful measures to slow its spread."

In Kazakhstan, HRW says that "President Kasym-Jomart Tokaev's promises for reform did not bring about meaningful improvements in... human rights record in 2020. Government critics faced harassment and prosecution, and free speech was suppressed, especially in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic."

In Kyrgyzstan "the death in custody of the wrongfully imprisoned human rights defender Azimjon Askarov in July was one of the low points of [the nation's] rights record during the year," says HRW. "Kyrgyzstan held parliamentary elections in October, which international observers found to be competitive but tainted by claims of vote buying."

Nevertheless, the Biden administration, like its predecessors, is keen to work with Central Asian regimes to achieve U.S. strategic objectives, even if regional dictators are less inclined to partner with Washington than they were before.

U.S. State Department spokesperson Ned Price said Wednesday that the Central Asian governments "will make sovereign decisions about their level of the cooperation with the United States" after American troops leave Afghanistan.

Price added that a stable post-U.S. withdrawal Afghanistan is "not only in our interests... it is much more and certainly in the immediate interests of Afghanistan's neighbors."

John Herbst, a former U.S. ambassador to Uzbekistan who was instrumental in securing American access to bases there after 9/11, told the AP that U.S. credibility in Central Asia has "taken a hit through our failures in Afghanistan."

"Is that a mortal hit? Probably not," said Herbst. "But it's still a very powerful factor."

The U.S. is vying with Russia--with which the Central Asian republics were united during the era of the former Soviet Union--China, and, increasingly, the Taliban, which has launched a neighborly charm offensive of its own, for influence in the region.

"Russia has strong historical, cultural, economic, and societal ties with the Central Asian region and is seeking to reassert its influence there, to counter the influence of actors from outside of the region, particularly the U.S.," Tracey German, a specialist in Russian foreign and security policy at the Defense Studies Department at King's College London, told Newsweek. "It views the region as its own strategic backyard."

Earlier this week, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said, "I would emphasize that the redeployment of the American permanent military presence to the countries neighboring Afghanistan is unacceptable."

"We told the Americans in a direct and straightforward way that it would change a lot of things not only in our perceptions of what's going on in that important region, but also in our relations with the United States," he added.

As for the Taliban, it has in recent months been dispatching its own diplomats to regional capitals in a bid to shore up relations with its neighbors. However, Herbst said that "all the countries in the region... have to worry about Taliban intentions."