ALEC and ExxonMobil Push Loopholes in Fracking Chemical Disclosure Rules

One of the key controversies about fracking is the chemical makeup of the fluid that is pumped deep into the ground to break apart rock and release natural gas. Some companies have been reluctant to disclose what's in their fracking fluid. Scientists and environmental advocates argue that, without knowing its precise composition, they can't thoroughly investigate complaints of contamination.

Disclosure requirements vary considerably from state to state, as ProPublica recently charted. In many cases, the rules have been limited by a "trade secrets" provision under which companies can claim that a proprietary chemical doesn't have to be disclosed to regulators or the public.

One apparent proponent of the trade secrets caveat? The American Legislative Exchange Council, better known as ALEC, a nonprofit group that brings together politicians and corporations to draft and promote conservative, business-friendly legislation. ALEC has been in the spotlight recently because of its support of controversial laws like Florida's "Stand Your Ground" provision.

This weekend, as part of a story on ALEC's political activity, The New York Times noted that the group recently adopted "model legislation" on fracking chemical disclosure, based on a bill passed in Texas last year. According to The Times, the model bill was "sponsored within ALEC" by ExxonMobil, which runs a major oil and gas operation through its subsidiary, XTO Energy. The advocacy group Common Cause, which provided the documents on ALEC's lobbying efforts to The Times, describes model legislation, in many cases identifying by name the company that proposed it to ALEC's task forces.

ALEC has recently removed its list of model bills from its main website, and did not respond to requests for comment. A spokesman for XTO Energy confirmed that the company is a member of ALEC, but he did not provide details on the company's involvement with the disclosure bill.

The spokesman said ExxonMobil supports "full disclosure of the ingredients and additives in hydraulic fracturing fluids," but added that when vendors request it, ExxonMobil has "respected the trade secret status of their products." Last year, the company began voluntarily uploading chemical disclosures to FracFocus, a clearinghouse website run by the Groundwater Protection Council and the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission.

In a recent blog post, ALEC claimed that legislators in Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, New York and Ohio have introduced versions of its model bill, but many of those states vary in the level of disclosure required and how they handle the trade secrets provision. Laws in 11 states require at least partial disclosure, and the Bureau of Land Management recently drafted disclosure guidelines for drilling on federal land.

These laws have been relatively well-received by environmental advocates, though the trade secrets issue remains a concern for some. In Ohio, for example, proprietary chemicals don't have to be disclosed to regulators or the public. In Pennsylvania, they are disclosed to regulators, and the public can request information on them from the state Department of Environmental Protection on a case-by-case basis.

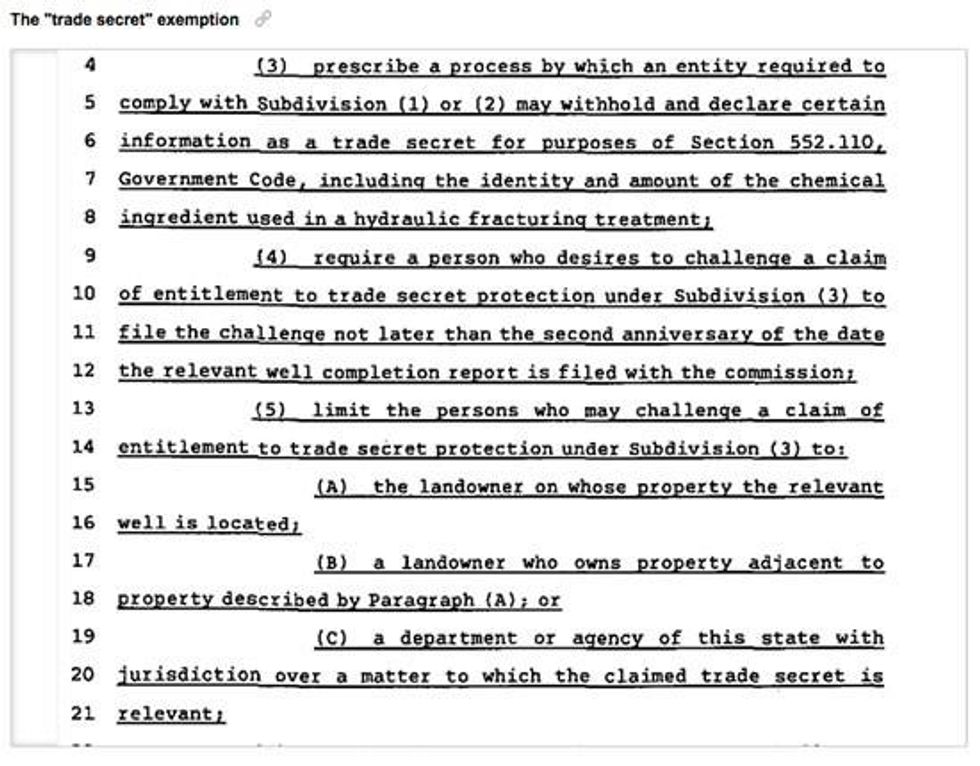

The Texas law, which ALEC cites in the post as its template, codifies the trade secrets exemption, and who can challenge it:

Otherwise, Texas' law requires that companies post disclosure forms for each completed well on the FracFocus site. They must disclose all chemicals but only report the concentrations of those that are hazardous. The law also requires that the companies give the total volume of water used in fracking.

The Environmental Protection Agency cannot regulate fracking in order to protect groundwater, because in 2005 Congress exempted fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act, which controls how industries inject substances underground.

According to ALEC's blog, the model disclosure legislation is designed to promote "responsible resource production" and "aims to preempt the promulgation of duplicative, burdensome federal regulations" from the EPA, in particular. ALEC has consistently opposed any federal control over fracking. In 2009, the group adopted a "Resolution to Retain State Authority Over Hydraulic Fracturing."

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

One of the key controversies about fracking is the chemical makeup of the fluid that is pumped deep into the ground to break apart rock and release natural gas. Some companies have been reluctant to disclose what's in their fracking fluid. Scientists and environmental advocates argue that, without knowing its precise composition, they can't thoroughly investigate complaints of contamination.

Disclosure requirements vary considerably from state to state, as ProPublica recently charted. In many cases, the rules have been limited by a "trade secrets" provision under which companies can claim that a proprietary chemical doesn't have to be disclosed to regulators or the public.

One apparent proponent of the trade secrets caveat? The American Legislative Exchange Council, better known as ALEC, a nonprofit group that brings together politicians and corporations to draft and promote conservative, business-friendly legislation. ALEC has been in the spotlight recently because of its support of controversial laws like Florida's "Stand Your Ground" provision.

This weekend, as part of a story on ALEC's political activity, The New York Times noted that the group recently adopted "model legislation" on fracking chemical disclosure, based on a bill passed in Texas last year. According to The Times, the model bill was "sponsored within ALEC" by ExxonMobil, which runs a major oil and gas operation through its subsidiary, XTO Energy. The advocacy group Common Cause, which provided the documents on ALEC's lobbying efforts to The Times, describes model legislation, in many cases identifying by name the company that proposed it to ALEC's task forces.

ALEC has recently removed its list of model bills from its main website, and did not respond to requests for comment. A spokesman for XTO Energy confirmed that the company is a member of ALEC, but he did not provide details on the company's involvement with the disclosure bill.

The spokesman said ExxonMobil supports "full disclosure of the ingredients and additives in hydraulic fracturing fluids," but added that when vendors request it, ExxonMobil has "respected the trade secret status of their products." Last year, the company began voluntarily uploading chemical disclosures to FracFocus, a clearinghouse website run by the Groundwater Protection Council and the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission.

In a recent blog post, ALEC claimed that legislators in Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, New York and Ohio have introduced versions of its model bill, but many of those states vary in the level of disclosure required and how they handle the trade secrets provision. Laws in 11 states require at least partial disclosure, and the Bureau of Land Management recently drafted disclosure guidelines for drilling on federal land.

These laws have been relatively well-received by environmental advocates, though the trade secrets issue remains a concern for some. In Ohio, for example, proprietary chemicals don't have to be disclosed to regulators or the public. In Pennsylvania, they are disclosed to regulators, and the public can request information on them from the state Department of Environmental Protection on a case-by-case basis.

The Texas law, which ALEC cites in the post as its template, codifies the trade secrets exemption, and who can challenge it:

Otherwise, Texas' law requires that companies post disclosure forms for each completed well on the FracFocus site. They must disclose all chemicals but only report the concentrations of those that are hazardous. The law also requires that the companies give the total volume of water used in fracking.

The Environmental Protection Agency cannot regulate fracking in order to protect groundwater, because in 2005 Congress exempted fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act, which controls how industries inject substances underground.

According to ALEC's blog, the model disclosure legislation is designed to promote "responsible resource production" and "aims to preempt the promulgation of duplicative, burdensome federal regulations" from the EPA, in particular. ALEC has consistently opposed any federal control over fracking. In 2009, the group adopted a "Resolution to Retain State Authority Over Hydraulic Fracturing."

One of the key controversies about fracking is the chemical makeup of the fluid that is pumped deep into the ground to break apart rock and release natural gas. Some companies have been reluctant to disclose what's in their fracking fluid. Scientists and environmental advocates argue that, without knowing its precise composition, they can't thoroughly investigate complaints of contamination.

Disclosure requirements vary considerably from state to state, as ProPublica recently charted. In many cases, the rules have been limited by a "trade secrets" provision under which companies can claim that a proprietary chemical doesn't have to be disclosed to regulators or the public.

One apparent proponent of the trade secrets caveat? The American Legislative Exchange Council, better known as ALEC, a nonprofit group that brings together politicians and corporations to draft and promote conservative, business-friendly legislation. ALEC has been in the spotlight recently because of its support of controversial laws like Florida's "Stand Your Ground" provision.

This weekend, as part of a story on ALEC's political activity, The New York Times noted that the group recently adopted "model legislation" on fracking chemical disclosure, based on a bill passed in Texas last year. According to The Times, the model bill was "sponsored within ALEC" by ExxonMobil, which runs a major oil and gas operation through its subsidiary, XTO Energy. The advocacy group Common Cause, which provided the documents on ALEC's lobbying efforts to The Times, describes model legislation, in many cases identifying by name the company that proposed it to ALEC's task forces.

ALEC has recently removed its list of model bills from its main website, and did not respond to requests for comment. A spokesman for XTO Energy confirmed that the company is a member of ALEC, but he did not provide details on the company's involvement with the disclosure bill.

The spokesman said ExxonMobil supports "full disclosure of the ingredients and additives in hydraulic fracturing fluids," but added that when vendors request it, ExxonMobil has "respected the trade secret status of their products." Last year, the company began voluntarily uploading chemical disclosures to FracFocus, a clearinghouse website run by the Groundwater Protection Council and the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission.

In a recent blog post, ALEC claimed that legislators in Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, New York and Ohio have introduced versions of its model bill, but many of those states vary in the level of disclosure required and how they handle the trade secrets provision. Laws in 11 states require at least partial disclosure, and the Bureau of Land Management recently drafted disclosure guidelines for drilling on federal land.

These laws have been relatively well-received by environmental advocates, though the trade secrets issue remains a concern for some. In Ohio, for example, proprietary chemicals don't have to be disclosed to regulators or the public. In Pennsylvania, they are disclosed to regulators, and the public can request information on them from the state Department of Environmental Protection on a case-by-case basis.

The Texas law, which ALEC cites in the post as its template, codifies the trade secrets exemption, and who can challenge it:

Otherwise, Texas' law requires that companies post disclosure forms for each completed well on the FracFocus site. They must disclose all chemicals but only report the concentrations of those that are hazardous. The law also requires that the companies give the total volume of water used in fracking.

The Environmental Protection Agency cannot regulate fracking in order to protect groundwater, because in 2005 Congress exempted fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act, which controls how industries inject substances underground.

According to ALEC's blog, the model disclosure legislation is designed to promote "responsible resource production" and "aims to preempt the promulgation of duplicative, burdensome federal regulations" from the EPA, in particular. ALEC has consistently opposed any federal control over fracking. In 2009, the group adopted a "Resolution to Retain State Authority Over Hydraulic Fracturing."