SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

If Bezos was still married to his ex-wife, MacKenzie Scott, together they would be worth another $60 billion or so--giving the couple a net worth of a quarter trillion dollars. (Photo: Andrej Sokolow/picture alliance via Getty Images)

The wealth of US billionaires has steadily grown over the last thirty-one years. But a third of $4.3 trillion in billionaire wealth gains since 1990 have come during the last 13 months of the pandemic.

Between 1990 and April 2021, the combined wealth of U.S. billionaires increased 19-fold, from $240 billion in today's dollars to $4.56 trillion in 2021. Below are the findings about billionaire wealth growth over the past 31 years (according to an analysis by Americans for Tax Fairness and the Institute for Policy Studies: see data sources and full report.)

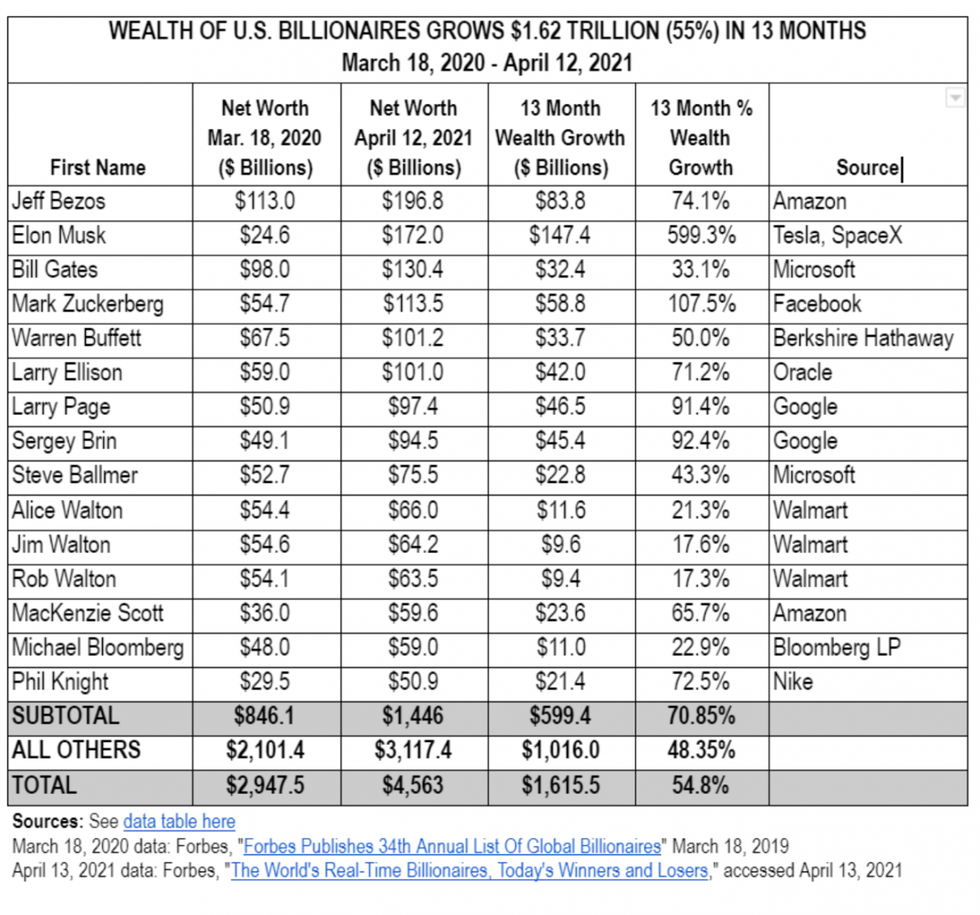

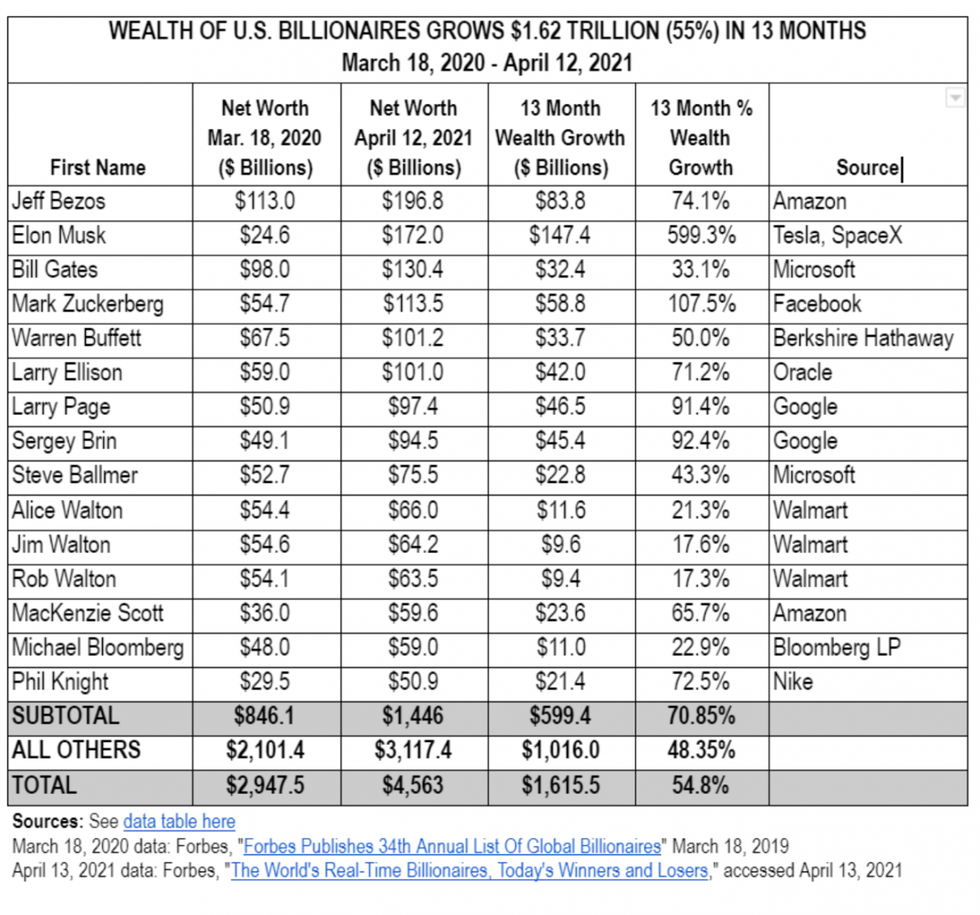

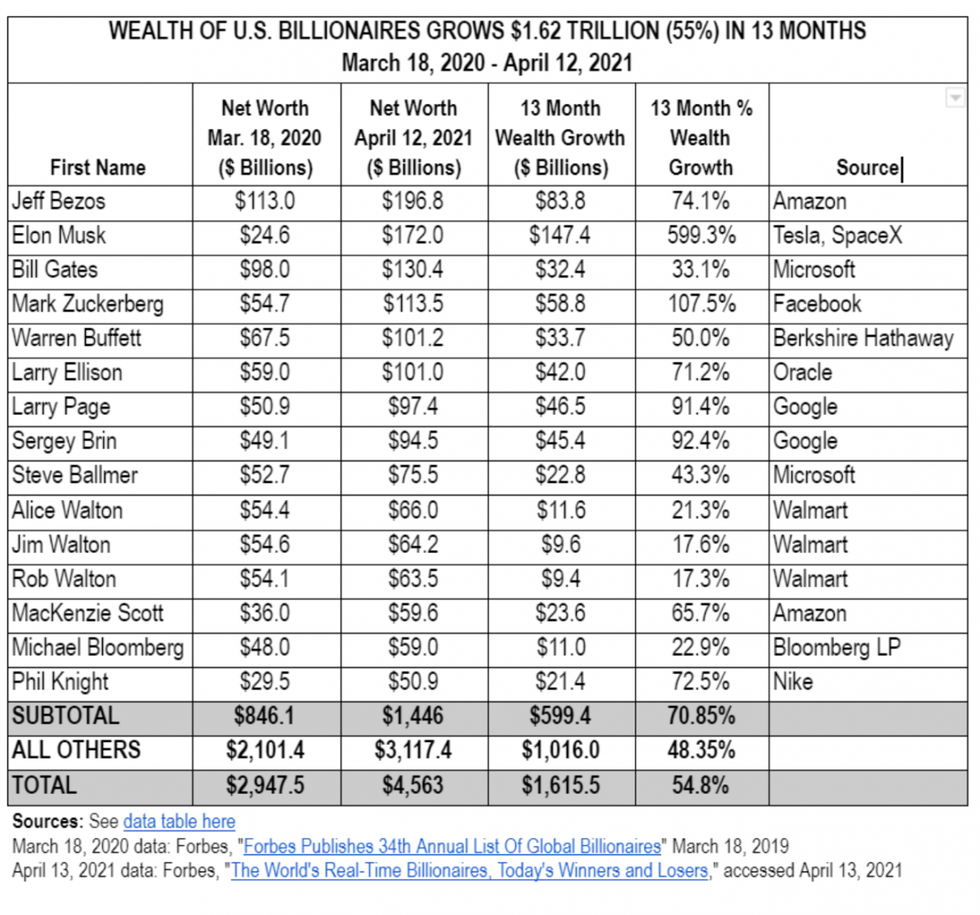

Between March 18, 2020, and April 12, 2021,the collective wealth of American billionaires leapt by $1.62 trillion, or 55 percent, from $2.95 trillion to $4.56 trillion. [See data table here].

America's 719 billionaires now hold over four times more wealth ($4.56 trillion) than all the roughly 165 million Americans in society's bottom half ($1.01 trillion), according to Federal Reserve Board data.

In 1990, the situation was reversed--billionaires were worth $240 billion and the bottom 50% had $380 billion in combined wealth.

Billionaires' huge pandemic-era wealth gains have come amid the past 13 months of coronavirus misery. During those same 13 months, over 30 million Americans fell ill from COVID, over 560,000 died from it and about 77 million lost jobs.

As of April 12, there were six American "centi-billionaires"--individuals each worth at least $100 billion [see table below]. That's bigger than the size of the economy of each of 13 of the nation's states. Here's how the wealth of these ultra-billionaires grew during the pandemic:

Background and Methodology

Periodically ATF and IPS report on historical trends in billionaire wealth growth since 1990 using Forbes annual billionaire wealth reports as the benchmark. This month Forbes released its 2021 report, based on wealth measured March 5. However, compared to Forbes real-time data reports since then there appear to have been anomalies in that report (e.g., there were 60 fewer billionaires on March 5 compared with April 12), so we are instead using April 12 real-time data for this comparison.

Household net worth holdings are calculated by taking the $2.49 billion that the Fed is reporting (on April 12) as the net worth of the bottom 50% of society, and backing out the Feds reported value of "consumer durables" from the reported "net worth" variable. This provides a more accurate picture of the wealth of the bottom half.

This method is based on New York University economist Edward Wolff, who argues that durable consumer goods -- like televisions, furniture, and household appliances -- are not easily marketed. Automobiles, the main durable good included in the Survey of Consumer Finances (one of the two component data sources for the DFA data), are slightly easier to sell. But cars typically lose rather than gain value over time, making them a weak store of wealth. Wolff's exclusion of automobiles is also consistent with the Federal Reserve's approach to national accounts, where vehicle purchases are listed as expenditures rather than savings.

For more on this methodology, see Wolff's National Bureau of Economic Research paper Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962-2013 and the Institute for Policy Studies' 2017 Billionaire Bonanza.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The wealth of US billionaires has steadily grown over the last thirty-one years. But a third of $4.3 trillion in billionaire wealth gains since 1990 have come during the last 13 months of the pandemic.

Between 1990 and April 2021, the combined wealth of U.S. billionaires increased 19-fold, from $240 billion in today's dollars to $4.56 trillion in 2021. Below are the findings about billionaire wealth growth over the past 31 years (according to an analysis by Americans for Tax Fairness and the Institute for Policy Studies: see data sources and full report.)

Between March 18, 2020, and April 12, 2021,the collective wealth of American billionaires leapt by $1.62 trillion, or 55 percent, from $2.95 trillion to $4.56 trillion. [See data table here].

America's 719 billionaires now hold over four times more wealth ($4.56 trillion) than all the roughly 165 million Americans in society's bottom half ($1.01 trillion), according to Federal Reserve Board data.

In 1990, the situation was reversed--billionaires were worth $240 billion and the bottom 50% had $380 billion in combined wealth.

Billionaires' huge pandemic-era wealth gains have come amid the past 13 months of coronavirus misery. During those same 13 months, over 30 million Americans fell ill from COVID, over 560,000 died from it and about 77 million lost jobs.

As of April 12, there were six American "centi-billionaires"--individuals each worth at least $100 billion [see table below]. That's bigger than the size of the economy of each of 13 of the nation's states. Here's how the wealth of these ultra-billionaires grew during the pandemic:

Background and Methodology

Periodically ATF and IPS report on historical trends in billionaire wealth growth since 1990 using Forbes annual billionaire wealth reports as the benchmark. This month Forbes released its 2021 report, based on wealth measured March 5. However, compared to Forbes real-time data reports since then there appear to have been anomalies in that report (e.g., there were 60 fewer billionaires on March 5 compared with April 12), so we are instead using April 12 real-time data for this comparison.

Household net worth holdings are calculated by taking the $2.49 billion that the Fed is reporting (on April 12) as the net worth of the bottom 50% of society, and backing out the Feds reported value of "consumer durables" from the reported "net worth" variable. This provides a more accurate picture of the wealth of the bottom half.

This method is based on New York University economist Edward Wolff, who argues that durable consumer goods -- like televisions, furniture, and household appliances -- are not easily marketed. Automobiles, the main durable good included in the Survey of Consumer Finances (one of the two component data sources for the DFA data), are slightly easier to sell. But cars typically lose rather than gain value over time, making them a weak store of wealth. Wolff's exclusion of automobiles is also consistent with the Federal Reserve's approach to national accounts, where vehicle purchases are listed as expenditures rather than savings.

For more on this methodology, see Wolff's National Bureau of Economic Research paper Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962-2013 and the Institute for Policy Studies' 2017 Billionaire Bonanza.

The wealth of US billionaires has steadily grown over the last thirty-one years. But a third of $4.3 trillion in billionaire wealth gains since 1990 have come during the last 13 months of the pandemic.

Between 1990 and April 2021, the combined wealth of U.S. billionaires increased 19-fold, from $240 billion in today's dollars to $4.56 trillion in 2021. Below are the findings about billionaire wealth growth over the past 31 years (according to an analysis by Americans for Tax Fairness and the Institute for Policy Studies: see data sources and full report.)

Between March 18, 2020, and April 12, 2021,the collective wealth of American billionaires leapt by $1.62 trillion, or 55 percent, from $2.95 trillion to $4.56 trillion. [See data table here].

America's 719 billionaires now hold over four times more wealth ($4.56 trillion) than all the roughly 165 million Americans in society's bottom half ($1.01 trillion), according to Federal Reserve Board data.

In 1990, the situation was reversed--billionaires were worth $240 billion and the bottom 50% had $380 billion in combined wealth.

Billionaires' huge pandemic-era wealth gains have come amid the past 13 months of coronavirus misery. During those same 13 months, over 30 million Americans fell ill from COVID, over 560,000 died from it and about 77 million lost jobs.

As of April 12, there were six American "centi-billionaires"--individuals each worth at least $100 billion [see table below]. That's bigger than the size of the economy of each of 13 of the nation's states. Here's how the wealth of these ultra-billionaires grew during the pandemic:

Background and Methodology

Periodically ATF and IPS report on historical trends in billionaire wealth growth since 1990 using Forbes annual billionaire wealth reports as the benchmark. This month Forbes released its 2021 report, based on wealth measured March 5. However, compared to Forbes real-time data reports since then there appear to have been anomalies in that report (e.g., there were 60 fewer billionaires on March 5 compared with April 12), so we are instead using April 12 real-time data for this comparison.

Household net worth holdings are calculated by taking the $2.49 billion that the Fed is reporting (on April 12) as the net worth of the bottom 50% of society, and backing out the Feds reported value of "consumer durables" from the reported "net worth" variable. This provides a more accurate picture of the wealth of the bottom half.

This method is based on New York University economist Edward Wolff, who argues that durable consumer goods -- like televisions, furniture, and household appliances -- are not easily marketed. Automobiles, the main durable good included in the Survey of Consumer Finances (one of the two component data sources for the DFA data), are slightly easier to sell. But cars typically lose rather than gain value over time, making them a weak store of wealth. Wolff's exclusion of automobiles is also consistent with the Federal Reserve's approach to national accounts, where vehicle purchases are listed as expenditures rather than savings.

For more on this methodology, see Wolff's National Bureau of Economic Research paper Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962-2013 and the Institute for Policy Studies' 2017 Billionaire Bonanza.