SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

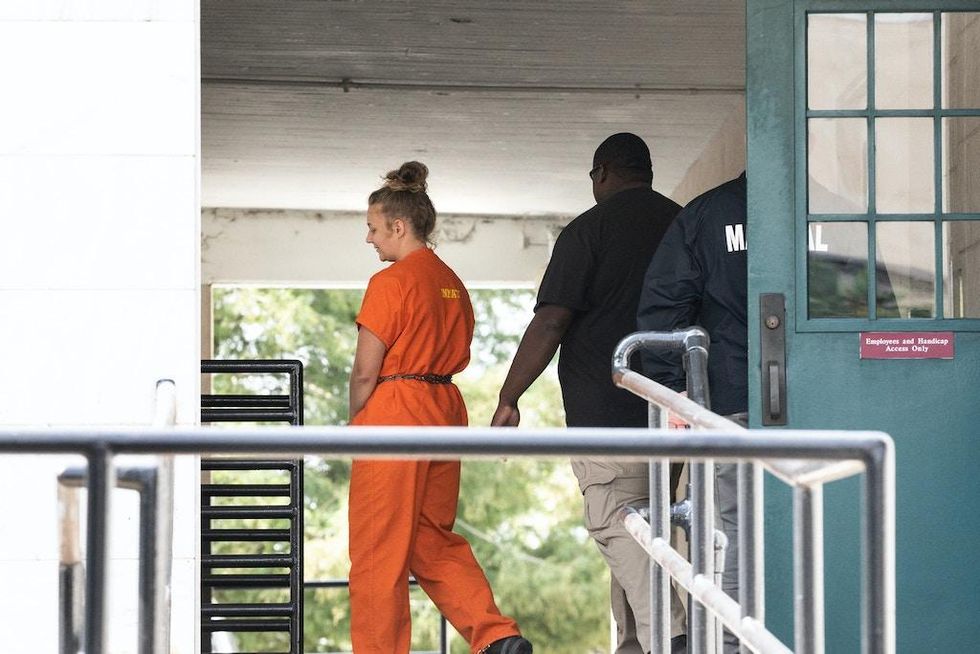

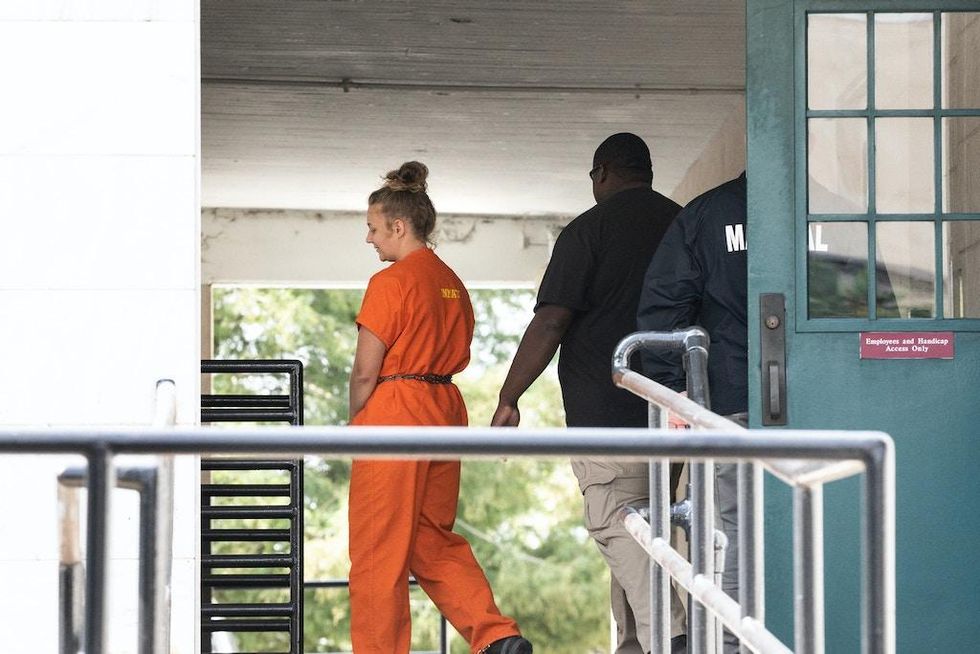

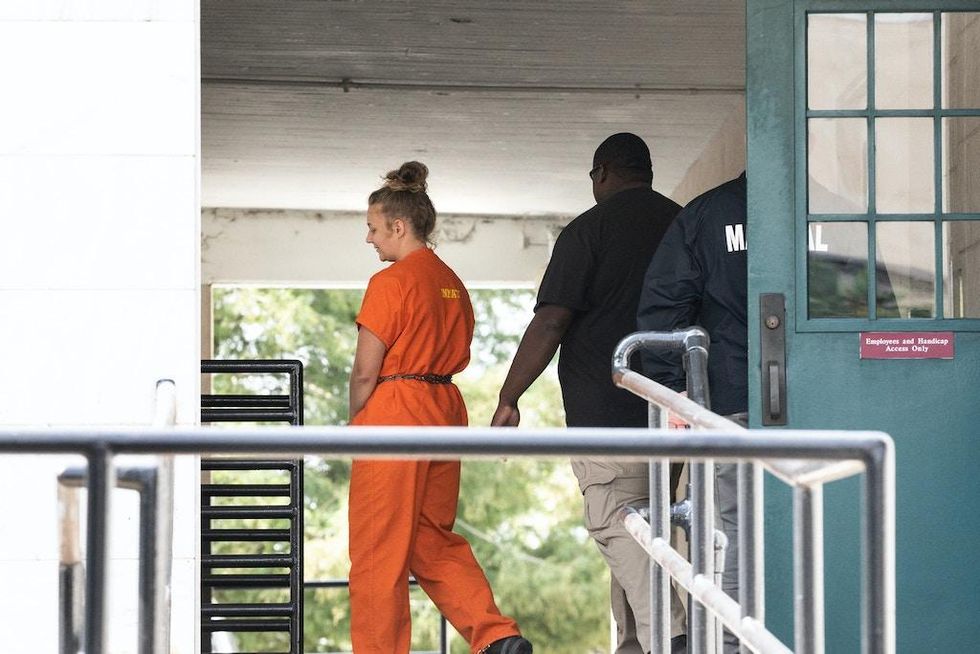

Reality Winner walks out of the Federal Courthouse in Augusta, Ga., on June 26, 2018. (Photo: Intercept)

The defense agreed to the plea deal in part to bring closure to Winner and her family. Her mother, Billie Winner-Davis, said when the plea was first announced that it was in her daughter's "best interest" since the Espionage Act does not afford her any public interest defense.

But it should not bring closure to the crucial issues raised by this case, namely, the Justice Department's contention that "national security" claims by the executive branch can never be challenged; that the executive branch has the sole authority to decide when information should be secret; and that the DOJ can prosecute journalists' sources for "harming" national security with no public evidence whatsoever.

The Justice Department's contention that "national security" claims by the executive branch can never be challenged; that the executive branch has the sole authority to decide when information should be secret; and that the DOJ can prosecute journalists' sources for "harming" national security with no public evidence whatsoever.

At issue in Winner's case is a document she leaked to a news outlet. The Intercept published an article on June 5, 2017 about a five-page National Security Agency report that detailed how alleged Russian hackers targeted election vendors with phishing attacks in an attempt to access voters rolls in several states. The Intercept was not aware of the identity of the source who provided the document, though other news organizations connected it to Winner.

In its sentencing memorandum two weeks ago, the prosecution made several dubious statements about why a sentence of this unprecedented length was necessary, chiefly that "the defendant's unauthorized disclosure caused exceptionally grave harm to our national security," a claim that was repeated several times. U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Georgia Bobby Christine, who was appointed last year by President Donald Trump, went further on Thursday, calling Winner "a quintessential example of an insider threat."

"Winner will serve a term of incarceration that will give pause to others who are entrusted with our country's sensitive national security information and would consider compromising it," Christine told reporters after the sentencing at the federal courthouse in Augusta, Ga. "Anyone else who may think of committing such an egregious and damaging wrong should take note of the prison sentence imposed today and the very real damage done."

The government did not produce one iota of public evidence to back up its claims, citing only an unnamed "expert" whose comments are completely classified, and referring to the "top secret" marking on the document that they say "by definition" proves their point.

But new evidence published by The Intercept for the first time today, along with one of Special Counsel Robert Mueller's recent indictments, undercuts the government's claims.

A key phrase that the government wanted withheld was the specific name of the Russian unit identified in the document. The government was particularly insistent on that point. Since it wasn't vital to the story that the unit's name be revealed, nor was it clear -- at least at the time -- that revealing the unit's name was in the public interest, The Intercept agreed to withhold it.

But in the indictment of alleged Russian military intelligence operatives that Mueller's office released last month, the Justice Department revealed the same name: GRU unit 74455. (The unit is also known as the Main Center for Special Technology or GTsST.) The indictment went on to reveal information almost identical to that contained in the document Winner admits to disclosing:

In or around June 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators researched domains used by U.S. state boards of elections, secretaries of state, and other election-related entities for website vulnerabilities. KOVALEV and his co-conspirators also searched for state political party email addresses, including filtered queries for email addresses listed on state Republican Party websites.

In or around July 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators hacked the website of a state board of elections ("SBOE 1") and stole information related to approximately 500,000 voters, including names, addresses, partial social security numbers, dates of birth, and driver's license numbers

In or around August 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators hacked into the computers of a U.S. vendor ("Vendor 1") that supplied software used to verify voter registration information for the 2016 U.S. elections. KOVALEV and his co-conspirators used some of the same infrastructure to hack into Vendor 1 that they had used to hack into SBOE 1.

The Justice Department is trying to have it both ways: It's OK for Mueller to publicly release this information in an attempt to prosecute alleged Russian hackers because it's in the public interest. But at the exact same time, the government is also claiming that a document including very similar information causes grave harm to national security when disclosed to the public by someone else.

Maybe timing was the issue, you might say. Maybe the government is arguing that the Winner document, released more than a year before the Mueller indictment, somehow could have tipped off the accused Russian operatives that the NSA was spying on them. But the special counsel's allegations point to a different conclusion.

In the indictment of the alleged Russian intelligence officers, the Special Counsel's Office describes how the FBI itself tipped off the GRU unit to the U.S. surveillance almost a year before The Intercept published the NSA document. As the indictment notes:

In or around August 2016, the FBI issued an alert about the hacking of SBOE 1 and identified some of the infrastructure that was used to conduct the hacking. In response, KOVALEV deleted his search history. KOVALEV and his co-conspirators also deleted records from accounts used in their operations targeting state boards of elections and similar election related materials.

If the GRU was already aware that the U.S. was watching its activities in 2016 -- thanks to the FBI and not the media -- how could the Winner document have "gravely harmed" national security almost a year later?

Even without the Mueller indictment, the claim that the release of the NSA document seriously endangered national security was specious to begin with. There were no "sources and methods" in anything The Intercept published. By the summer of 2017, Russia's attempted cyberattacks around the 2016 election had been widely reported.

Regardless of the government's claims, it should be crystal clear to anyone who reads the newspaper that there is significant public interest in the information that Winner has admitted to disclosing. Russian interference in the 2016 election is still front-page news almost two years later. The federal government kept several states allegedly targeted by hackers in the dark about the specifics of these attacks until The Intercept published its story.

Regardless of the government's claims, it should be crystal clear to anyone who reads the newspaper that there is significant public interest in the information that Winner has admitted to disclosing.

In fact, the day after The Intercept's story came out, the Election Assistance Commission -- the federal agency in charge of assisting state election officials -- wrote an urgent bulletin to states, calling the report "credible" and urging state officials to read it. The EAC then provided advice on how to take action. (The commission, unbelievably, tweeted the hashtag #RealityWinner to promote its bulletin on social media).

The long history of the U.S. government claiming that a document published by the press was a "closely held" secret -- when in fact it was anything but -- may be why J. William Leonard, the former classification czar under George W. Bush, agreed to act as a defense witness for Reality Winner on a pro bono basis. Since leaving office in the mid-2000s, Leonard has sought to draw attention to abuses within the U.S. government classification regime and has acted as an expert witness in several leak investigations.

Leonard has also testified to Congress several times about our broken secrecy system. In 2016, he spoke before the House Oversight Committee about leak prosecutions similar to Winner's: "The opaque nature of the classification system can give the government a unilateral and almost insurmountable advantage when it is engaged in an adversary encounter with one of its own citizens, an advantage that is just too tempting for many government officials to resist."

He went on to explain in his congressional testimony that even as government employees are regularly and harshly punished for revealing information that the government considers secret, "to my knowledge no one has ever been held accountable and subjected to sanctions for abusing the classification system or for improperly classifying information."

Leonard never got to testify in the Winner trial, so the court will never hear his expert opinion on the document at issue. What we do know is that the executive branch under both parties has insisted for decades that the classification of documents is virtually unreviewable by either the judiciary branch or Congress. And history is littered with examples of the government abusing its classification authority.

If you want to understand how the government classifies virtually any information in the national security space, no matter how benign, just read this recent account from BuzzFeed's Jason Leopold about an "illegal animal killing" on CIA property involving a government employee. After Leopold got wind of an Inspector General report on the subject, he filed a FOIA request for more information. The CIA stonewalled him and withheld the IG report on the incident in full, claiming it would "harm national security" to release it -- or even to disclose the type of animal that was killed.

So Leopold sued. Three years later, the government finally relented and revealed that the animal in question was a deer. The rest of the report remains classified.

It is, of course, conceivable that some unknown detail in the document Winner disclosed could have caused consternation at NSA headquarters. But because the government will never tell the public how something "damaged" national security, and uses the secrecy system to ensure that its arguments cannot be challenged, we'll never know.

We'll also never know exactly how much national security damage the government caused by not releasing this information to state election officials and the public much earlier.

We'll also never know exactly how much national security damage the government caused by not releasing this information to state election officials and the public much earlier.

In Augusta on Thursday, Winner spoke about her now-deceased father, who she said "expected us to engage in intellectual discourse as soon as we were out of diapers." She said that like many Americans, her family was deeply affected by the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, which sparked her interest in"the languages and the cultures of the countries involved." Winner joined the Air Force, then left to further her education and seek humanitarian work. She took a job at the government contractor Pluribus to "improve the language skills I developed in the Air Force.

In a small measure of relief for Winner and her advocates, Judge Randal Hall endorsed her request to be sent to FMC Carswell, a Forth Worth federal medical facility where she will be about a seven-hour drive from her family in Kingsville, Texas. In court, Winner mentioned her 12-year struggle with bulimia, calling it "the most pressing internal challenge in my day-to-day survival," and said that seeking treatment is one of her top goals. Her defense attorneys requested the Fort Worth facility so Winner could receive adequate medical care and "further her humanitarian objectives" through assisting other inmates with "debilitating illnesses."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The defense agreed to the plea deal in part to bring closure to Winner and her family. Her mother, Billie Winner-Davis, said when the plea was first announced that it was in her daughter's "best interest" since the Espionage Act does not afford her any public interest defense.

But it should not bring closure to the crucial issues raised by this case, namely, the Justice Department's contention that "national security" claims by the executive branch can never be challenged; that the executive branch has the sole authority to decide when information should be secret; and that the DOJ can prosecute journalists' sources for "harming" national security with no public evidence whatsoever.

The Justice Department's contention that "national security" claims by the executive branch can never be challenged; that the executive branch has the sole authority to decide when information should be secret; and that the DOJ can prosecute journalists' sources for "harming" national security with no public evidence whatsoever.

At issue in Winner's case is a document she leaked to a news outlet. The Intercept published an article on June 5, 2017 about a five-page National Security Agency report that detailed how alleged Russian hackers targeted election vendors with phishing attacks in an attempt to access voters rolls in several states. The Intercept was not aware of the identity of the source who provided the document, though other news organizations connected it to Winner.

In its sentencing memorandum two weeks ago, the prosecution made several dubious statements about why a sentence of this unprecedented length was necessary, chiefly that "the defendant's unauthorized disclosure caused exceptionally grave harm to our national security," a claim that was repeated several times. U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Georgia Bobby Christine, who was appointed last year by President Donald Trump, went further on Thursday, calling Winner "a quintessential example of an insider threat."

"Winner will serve a term of incarceration that will give pause to others who are entrusted with our country's sensitive national security information and would consider compromising it," Christine told reporters after the sentencing at the federal courthouse in Augusta, Ga. "Anyone else who may think of committing such an egregious and damaging wrong should take note of the prison sentence imposed today and the very real damage done."

The government did not produce one iota of public evidence to back up its claims, citing only an unnamed "expert" whose comments are completely classified, and referring to the "top secret" marking on the document that they say "by definition" proves their point.

But new evidence published by The Intercept for the first time today, along with one of Special Counsel Robert Mueller's recent indictments, undercuts the government's claims.

A key phrase that the government wanted withheld was the specific name of the Russian unit identified in the document. The government was particularly insistent on that point. Since it wasn't vital to the story that the unit's name be revealed, nor was it clear -- at least at the time -- that revealing the unit's name was in the public interest, The Intercept agreed to withhold it.

But in the indictment of alleged Russian military intelligence operatives that Mueller's office released last month, the Justice Department revealed the same name: GRU unit 74455. (The unit is also known as the Main Center for Special Technology or GTsST.) The indictment went on to reveal information almost identical to that contained in the document Winner admits to disclosing:

In or around June 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators researched domains used by U.S. state boards of elections, secretaries of state, and other election-related entities for website vulnerabilities. KOVALEV and his co-conspirators also searched for state political party email addresses, including filtered queries for email addresses listed on state Republican Party websites.

In or around July 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators hacked the website of a state board of elections ("SBOE 1") and stole information related to approximately 500,000 voters, including names, addresses, partial social security numbers, dates of birth, and driver's license numbers

In or around August 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators hacked into the computers of a U.S. vendor ("Vendor 1") that supplied software used to verify voter registration information for the 2016 U.S. elections. KOVALEV and his co-conspirators used some of the same infrastructure to hack into Vendor 1 that they had used to hack into SBOE 1.

The Justice Department is trying to have it both ways: It's OK for Mueller to publicly release this information in an attempt to prosecute alleged Russian hackers because it's in the public interest. But at the exact same time, the government is also claiming that a document including very similar information causes grave harm to national security when disclosed to the public by someone else.

Maybe timing was the issue, you might say. Maybe the government is arguing that the Winner document, released more than a year before the Mueller indictment, somehow could have tipped off the accused Russian operatives that the NSA was spying on them. But the special counsel's allegations point to a different conclusion.

In the indictment of the alleged Russian intelligence officers, the Special Counsel's Office describes how the FBI itself tipped off the GRU unit to the U.S. surveillance almost a year before The Intercept published the NSA document. As the indictment notes:

In or around August 2016, the FBI issued an alert about the hacking of SBOE 1 and identified some of the infrastructure that was used to conduct the hacking. In response, KOVALEV deleted his search history. KOVALEV and his co-conspirators also deleted records from accounts used in their operations targeting state boards of elections and similar election related materials.

If the GRU was already aware that the U.S. was watching its activities in 2016 -- thanks to the FBI and not the media -- how could the Winner document have "gravely harmed" national security almost a year later?

Even without the Mueller indictment, the claim that the release of the NSA document seriously endangered national security was specious to begin with. There were no "sources and methods" in anything The Intercept published. By the summer of 2017, Russia's attempted cyberattacks around the 2016 election had been widely reported.

Regardless of the government's claims, it should be crystal clear to anyone who reads the newspaper that there is significant public interest in the information that Winner has admitted to disclosing. Russian interference in the 2016 election is still front-page news almost two years later. The federal government kept several states allegedly targeted by hackers in the dark about the specifics of these attacks until The Intercept published its story.

Regardless of the government's claims, it should be crystal clear to anyone who reads the newspaper that there is significant public interest in the information that Winner has admitted to disclosing.

In fact, the day after The Intercept's story came out, the Election Assistance Commission -- the federal agency in charge of assisting state election officials -- wrote an urgent bulletin to states, calling the report "credible" and urging state officials to read it. The EAC then provided advice on how to take action. (The commission, unbelievably, tweeted the hashtag #RealityWinner to promote its bulletin on social media).

The long history of the U.S. government claiming that a document published by the press was a "closely held" secret -- when in fact it was anything but -- may be why J. William Leonard, the former classification czar under George W. Bush, agreed to act as a defense witness for Reality Winner on a pro bono basis. Since leaving office in the mid-2000s, Leonard has sought to draw attention to abuses within the U.S. government classification regime and has acted as an expert witness in several leak investigations.

Leonard has also testified to Congress several times about our broken secrecy system. In 2016, he spoke before the House Oversight Committee about leak prosecutions similar to Winner's: "The opaque nature of the classification system can give the government a unilateral and almost insurmountable advantage when it is engaged in an adversary encounter with one of its own citizens, an advantage that is just too tempting for many government officials to resist."

He went on to explain in his congressional testimony that even as government employees are regularly and harshly punished for revealing information that the government considers secret, "to my knowledge no one has ever been held accountable and subjected to sanctions for abusing the classification system or for improperly classifying information."

Leonard never got to testify in the Winner trial, so the court will never hear his expert opinion on the document at issue. What we do know is that the executive branch under both parties has insisted for decades that the classification of documents is virtually unreviewable by either the judiciary branch or Congress. And history is littered with examples of the government abusing its classification authority.

If you want to understand how the government classifies virtually any information in the national security space, no matter how benign, just read this recent account from BuzzFeed's Jason Leopold about an "illegal animal killing" on CIA property involving a government employee. After Leopold got wind of an Inspector General report on the subject, he filed a FOIA request for more information. The CIA stonewalled him and withheld the IG report on the incident in full, claiming it would "harm national security" to release it -- or even to disclose the type of animal that was killed.

So Leopold sued. Three years later, the government finally relented and revealed that the animal in question was a deer. The rest of the report remains classified.

It is, of course, conceivable that some unknown detail in the document Winner disclosed could have caused consternation at NSA headquarters. But because the government will never tell the public how something "damaged" national security, and uses the secrecy system to ensure that its arguments cannot be challenged, we'll never know.

We'll also never know exactly how much national security damage the government caused by not releasing this information to state election officials and the public much earlier.

We'll also never know exactly how much national security damage the government caused by not releasing this information to state election officials and the public much earlier.

In Augusta on Thursday, Winner spoke about her now-deceased father, who she said "expected us to engage in intellectual discourse as soon as we were out of diapers." She said that like many Americans, her family was deeply affected by the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, which sparked her interest in"the languages and the cultures of the countries involved." Winner joined the Air Force, then left to further her education and seek humanitarian work. She took a job at the government contractor Pluribus to "improve the language skills I developed in the Air Force.

In a small measure of relief for Winner and her advocates, Judge Randal Hall endorsed her request to be sent to FMC Carswell, a Forth Worth federal medical facility where she will be about a seven-hour drive from her family in Kingsville, Texas. In court, Winner mentioned her 12-year struggle with bulimia, calling it "the most pressing internal challenge in my day-to-day survival," and said that seeking treatment is one of her top goals. Her defense attorneys requested the Fort Worth facility so Winner could receive adequate medical care and "further her humanitarian objectives" through assisting other inmates with "debilitating illnesses."

The defense agreed to the plea deal in part to bring closure to Winner and her family. Her mother, Billie Winner-Davis, said when the plea was first announced that it was in her daughter's "best interest" since the Espionage Act does not afford her any public interest defense.

But it should not bring closure to the crucial issues raised by this case, namely, the Justice Department's contention that "national security" claims by the executive branch can never be challenged; that the executive branch has the sole authority to decide when information should be secret; and that the DOJ can prosecute journalists' sources for "harming" national security with no public evidence whatsoever.

The Justice Department's contention that "national security" claims by the executive branch can never be challenged; that the executive branch has the sole authority to decide when information should be secret; and that the DOJ can prosecute journalists' sources for "harming" national security with no public evidence whatsoever.

At issue in Winner's case is a document she leaked to a news outlet. The Intercept published an article on June 5, 2017 about a five-page National Security Agency report that detailed how alleged Russian hackers targeted election vendors with phishing attacks in an attempt to access voters rolls in several states. The Intercept was not aware of the identity of the source who provided the document, though other news organizations connected it to Winner.

In its sentencing memorandum two weeks ago, the prosecution made several dubious statements about why a sentence of this unprecedented length was necessary, chiefly that "the defendant's unauthorized disclosure caused exceptionally grave harm to our national security," a claim that was repeated several times. U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Georgia Bobby Christine, who was appointed last year by President Donald Trump, went further on Thursday, calling Winner "a quintessential example of an insider threat."

"Winner will serve a term of incarceration that will give pause to others who are entrusted with our country's sensitive national security information and would consider compromising it," Christine told reporters after the sentencing at the federal courthouse in Augusta, Ga. "Anyone else who may think of committing such an egregious and damaging wrong should take note of the prison sentence imposed today and the very real damage done."

The government did not produce one iota of public evidence to back up its claims, citing only an unnamed "expert" whose comments are completely classified, and referring to the "top secret" marking on the document that they say "by definition" proves their point.

But new evidence published by The Intercept for the first time today, along with one of Special Counsel Robert Mueller's recent indictments, undercuts the government's claims.

A key phrase that the government wanted withheld was the specific name of the Russian unit identified in the document. The government was particularly insistent on that point. Since it wasn't vital to the story that the unit's name be revealed, nor was it clear -- at least at the time -- that revealing the unit's name was in the public interest, The Intercept agreed to withhold it.

But in the indictment of alleged Russian military intelligence operatives that Mueller's office released last month, the Justice Department revealed the same name: GRU unit 74455. (The unit is also known as the Main Center for Special Technology or GTsST.) The indictment went on to reveal information almost identical to that contained in the document Winner admits to disclosing:

In or around June 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators researched domains used by U.S. state boards of elections, secretaries of state, and other election-related entities for website vulnerabilities. KOVALEV and his co-conspirators also searched for state political party email addresses, including filtered queries for email addresses listed on state Republican Party websites.

In or around July 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators hacked the website of a state board of elections ("SBOE 1") and stole information related to approximately 500,000 voters, including names, addresses, partial social security numbers, dates of birth, and driver's license numbers

In or around August 2016, KOVALEV and his co-conspirators hacked into the computers of a U.S. vendor ("Vendor 1") that supplied software used to verify voter registration information for the 2016 U.S. elections. KOVALEV and his co-conspirators used some of the same infrastructure to hack into Vendor 1 that they had used to hack into SBOE 1.

The Justice Department is trying to have it both ways: It's OK for Mueller to publicly release this information in an attempt to prosecute alleged Russian hackers because it's in the public interest. But at the exact same time, the government is also claiming that a document including very similar information causes grave harm to national security when disclosed to the public by someone else.

Maybe timing was the issue, you might say. Maybe the government is arguing that the Winner document, released more than a year before the Mueller indictment, somehow could have tipped off the accused Russian operatives that the NSA was spying on them. But the special counsel's allegations point to a different conclusion.

In the indictment of the alleged Russian intelligence officers, the Special Counsel's Office describes how the FBI itself tipped off the GRU unit to the U.S. surveillance almost a year before The Intercept published the NSA document. As the indictment notes:

In or around August 2016, the FBI issued an alert about the hacking of SBOE 1 and identified some of the infrastructure that was used to conduct the hacking. In response, KOVALEV deleted his search history. KOVALEV and his co-conspirators also deleted records from accounts used in their operations targeting state boards of elections and similar election related materials.

If the GRU was already aware that the U.S. was watching its activities in 2016 -- thanks to the FBI and not the media -- how could the Winner document have "gravely harmed" national security almost a year later?

Even without the Mueller indictment, the claim that the release of the NSA document seriously endangered national security was specious to begin with. There were no "sources and methods" in anything The Intercept published. By the summer of 2017, Russia's attempted cyberattacks around the 2016 election had been widely reported.

Regardless of the government's claims, it should be crystal clear to anyone who reads the newspaper that there is significant public interest in the information that Winner has admitted to disclosing. Russian interference in the 2016 election is still front-page news almost two years later. The federal government kept several states allegedly targeted by hackers in the dark about the specifics of these attacks until The Intercept published its story.

Regardless of the government's claims, it should be crystal clear to anyone who reads the newspaper that there is significant public interest in the information that Winner has admitted to disclosing.

In fact, the day after The Intercept's story came out, the Election Assistance Commission -- the federal agency in charge of assisting state election officials -- wrote an urgent bulletin to states, calling the report "credible" and urging state officials to read it. The EAC then provided advice on how to take action. (The commission, unbelievably, tweeted the hashtag #RealityWinner to promote its bulletin on social media).

The long history of the U.S. government claiming that a document published by the press was a "closely held" secret -- when in fact it was anything but -- may be why J. William Leonard, the former classification czar under George W. Bush, agreed to act as a defense witness for Reality Winner on a pro bono basis. Since leaving office in the mid-2000s, Leonard has sought to draw attention to abuses within the U.S. government classification regime and has acted as an expert witness in several leak investigations.

Leonard has also testified to Congress several times about our broken secrecy system. In 2016, he spoke before the House Oversight Committee about leak prosecutions similar to Winner's: "The opaque nature of the classification system can give the government a unilateral and almost insurmountable advantage when it is engaged in an adversary encounter with one of its own citizens, an advantage that is just too tempting for many government officials to resist."

He went on to explain in his congressional testimony that even as government employees are regularly and harshly punished for revealing information that the government considers secret, "to my knowledge no one has ever been held accountable and subjected to sanctions for abusing the classification system or for improperly classifying information."

Leonard never got to testify in the Winner trial, so the court will never hear his expert opinion on the document at issue. What we do know is that the executive branch under both parties has insisted for decades that the classification of documents is virtually unreviewable by either the judiciary branch or Congress. And history is littered with examples of the government abusing its classification authority.

If you want to understand how the government classifies virtually any information in the national security space, no matter how benign, just read this recent account from BuzzFeed's Jason Leopold about an "illegal animal killing" on CIA property involving a government employee. After Leopold got wind of an Inspector General report on the subject, he filed a FOIA request for more information. The CIA stonewalled him and withheld the IG report on the incident in full, claiming it would "harm national security" to release it -- or even to disclose the type of animal that was killed.

So Leopold sued. Three years later, the government finally relented and revealed that the animal in question was a deer. The rest of the report remains classified.

It is, of course, conceivable that some unknown detail in the document Winner disclosed could have caused consternation at NSA headquarters. But because the government will never tell the public how something "damaged" national security, and uses the secrecy system to ensure that its arguments cannot be challenged, we'll never know.

We'll also never know exactly how much national security damage the government caused by not releasing this information to state election officials and the public much earlier.

We'll also never know exactly how much national security damage the government caused by not releasing this information to state election officials and the public much earlier.

In Augusta on Thursday, Winner spoke about her now-deceased father, who she said "expected us to engage in intellectual discourse as soon as we were out of diapers." She said that like many Americans, her family was deeply affected by the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, which sparked her interest in"the languages and the cultures of the countries involved." Winner joined the Air Force, then left to further her education and seek humanitarian work. She took a job at the government contractor Pluribus to "improve the language skills I developed in the Air Force.

In a small measure of relief for Winner and her advocates, Judge Randal Hall endorsed her request to be sent to FMC Carswell, a Forth Worth federal medical facility where she will be about a seven-hour drive from her family in Kingsville, Texas. In court, Winner mentioned her 12-year struggle with bulimia, calling it "the most pressing internal challenge in my day-to-day survival," and said that seeking treatment is one of her top goals. Her defense attorneys requested the Fort Worth facility so Winner could receive adequate medical care and "further her humanitarian objectives" through assisting other inmates with "debilitating illnesses."