SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

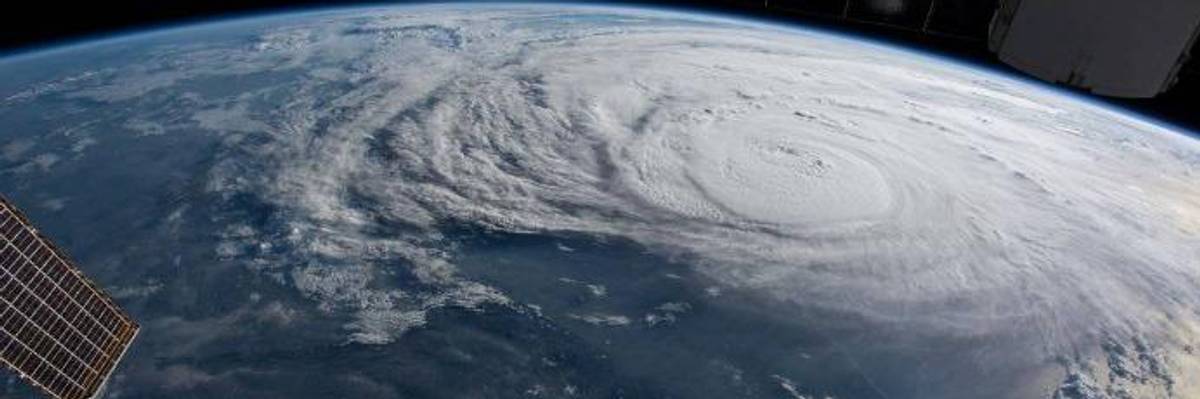

Hurricane Harvey is pictured off the coast of Texas, U.S. from aboard the International Space Station in this Aug. 25, 2017 NASA handout photo. (Photo: NASA handout)

Yesterday, the Governor of Texas warned that the bill for reconstruction after Superstorm Harvey could be as high as $180 billion. To put this into perspective, this is much worse that Hurricane Katrina.

It also does not include the hidden huge impact on local health and the environment from the toxic release of dozens of chemicals from the state's petrochemical infrastructure - from refineries, chemical plants to toxic pits.

Yesterday, the Governor of Texas warned that the bill for reconstruction after Superstorm Harvey could be as high as $180 billion. To put this into perspective, this is much worse that Hurricane Katrina.

It also does not include the hidden huge impact on local health and the environment from the toxic release of dozens of chemicals from the state's petrochemical infrastructure - from refineries, chemical plants to toxic pits.

Brock Long, the Head of the Government's Disaster Management Agency, also told CBS News that Harvey should be a wake-up call for local officials. "It is a wake-up call for this country for local and state elected officials to give their governors and their emergency management directors the full budgets that they need to be fully staffed, to design rainy-day funds, to have your own stand-alone individual assistance and public assistance programmes," he said.

The disaster should also be a wake-up call to the climate-denying President that unless he acts on climate, there will be more Harveys.

It is a wake-up call to the media to accurately report the disaster, including how climate change fuelled its intensity. It is also a wake-up call to the oil industry in so many, many ways.

On a national and international level it shows how our continuing dependence on fossil fuels will drive more extreme weather events. On a regional level it shows how ill-prepared the fossil fuel industry - and wider petrochemical industry - were to an event like this, despite decades of warnings.

Instead the fossil fuel industry's complacency, malaise, self-regulation and capture of the political system are all to blame too. They have led to a system of peril.

Antoine Halff is director of the Global Oil Markets Research Program at the Center on Global Energy Policy, at Columbia University, notes in the Financial Times: "Like Katrina, Harvey shows how exposed the US energy sector remains to the risk of weather disruptions. As global warming raises the threat of catastrophic weather events, this vulnerability may be rising."

Ironically, since Katrina, the US oil industry has become more vulnerable to climate disasters, rather than less, buoyed by the shale boom.

"One of the unexpected consequences of the US shale boom is the rising co-vulnerability of its increasingly complex and integrated energy system", notes Halff: "Even inland plays such as the Permian, the shale industry's star performer, seemingly out of harm's way, have become exposed to the risk of weather disruptions at coastal refineries, pipelines and export facilities on which they depend for market access."

The US shale industry built that infrastructure knowing that its refineries and pipelines were vulnerable to climate disasters. But short term profit always wins.

Nearly half the country's refining capacity is in harm's way on the Gulf Coast. This capacity is vulnerable to storms, hurricanes and super-storms, all of which will become more frequent with climate change. The oil industry knew this. But they built anyway.

They also knew that their refineries would cause significant pollution if they were caught up in a super storm like Harvey. But they built anyway.

To give you just one small example. In an article for the New York Times last October, entitled "When the Next Hurricane Hits Texas", Roy Scranton, an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Notre Dame, wrote: "Imagine a hurricane ... aimed straight at the heart of the American petrochemical industry." In his article he named an imaginary Hurricane called Isaiah, which "crashes through refineries, chemical storage facilities, wharves and production plants" such as Exxon's Baytown refinery: "It's an imaginary calamity based on research and models. The bad news is that it's only a matter of time before it does."

And only a matter of time it was. It took less than a year for Harvey to hit.

At its height, Harvey caused eleven refineries to be shut down. As Zoe Schlanger explains on the Quartz website, when refineries are forced to shut down, "they often release far greater volumes of toxic air pollution than the normal legal limits would allow."

One of those was Exxon's Baytown, which "released about double the amount of volatile organic compounds--a broad category of air toxics--than its permit normally allows". Shell also shut down its Deer Park refinery, releasing excess amounts of the cancer causing chemical benzene, amongst others.

Schlanger adds: "In industry parlance, these pollution spikes are called 'exceptional events'. The excess pollution is considered an emergency necessity to prevent worse outcomes, like an explosion, so plants are exempt from fines they would ordinarily pay for exceeding their legal pollution limits." So the system allows the industry to poison the local population even more in times of trouble.

As Harvey's rain intensified, some refineries in the path of the storm began to flare excess chemicals, directly impacting the poorer, Latino communities in Houston's East End. At the height of the storm, the local communities were reporting strong gas and chemical-like smells. "I've been smelling them all night and off and on this morning," Bryan Parras, an activist at the grassroots environmental justice group TEJAS, from Housten's East End, told the New Republic.

Parras added said some residents were experiencing "headaches, sore throat, scratchy throat and itchy eyes." But due to the rising flood waters, the residents were trapped, breathing in the toxic air. "Fenceline communities can't leave or evacuate so they are literally getting gassed by these chemicals," Parras added.

Nor was it just refineries. The Associated Press has explored Harvey's impact on toxic Superfund sites, a legacy of the oil and gas industry, of which there are dozens in the Houston area.

The AP "surveyed seven Superfund sites in and around Houston during the flooding. All had been inundated with water, in some cases many feet deep". Later the Environmetnal Protection Agency would confirm that over a dozen sites had been damaged.

When the AP visited one site, San Jacinto River Waste Pits Superfund site, it was "completely covered with floodwaters ... The flow from the raging river washing over the toxic site was so intense it damaged an adjacent section of the Interstate 10 bridge ... There was no way to immediately assess how much contaminated soil from the site might have been washed away."

Then of course we have had the wide petrochemical plants, one of which exploded last week. The response from the company was to let it "burn itself out". Where, you might well ask, was the emergency plan to prevent this happening?

Two years ago, the local newspaper, The Houston Chronicle documented the total lax safety standards of the petrochemical industry in the state in a must-read eight-part series.

At the time, Ron White, the former director of regulatory policy at the Center for Effective Government, told the paper that "It will take another disaster" before the authorites started to reign in the petrochemical industry and take pre-emptive action.

That disaster has now happened. Now is the time to act. Before another storm hits.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Yesterday, the Governor of Texas warned that the bill for reconstruction after Superstorm Harvey could be as high as $180 billion. To put this into perspective, this is much worse that Hurricane Katrina.

It also does not include the hidden huge impact on local health and the environment from the toxic release of dozens of chemicals from the state's petrochemical infrastructure - from refineries, chemical plants to toxic pits.

Brock Long, the Head of the Government's Disaster Management Agency, also told CBS News that Harvey should be a wake-up call for local officials. "It is a wake-up call for this country for local and state elected officials to give their governors and their emergency management directors the full budgets that they need to be fully staffed, to design rainy-day funds, to have your own stand-alone individual assistance and public assistance programmes," he said.

The disaster should also be a wake-up call to the climate-denying President that unless he acts on climate, there will be more Harveys.

It is a wake-up call to the media to accurately report the disaster, including how climate change fuelled its intensity. It is also a wake-up call to the oil industry in so many, many ways.

On a national and international level it shows how our continuing dependence on fossil fuels will drive more extreme weather events. On a regional level it shows how ill-prepared the fossil fuel industry - and wider petrochemical industry - were to an event like this, despite decades of warnings.

Instead the fossil fuel industry's complacency, malaise, self-regulation and capture of the political system are all to blame too. They have led to a system of peril.

Antoine Halff is director of the Global Oil Markets Research Program at the Center on Global Energy Policy, at Columbia University, notes in the Financial Times: "Like Katrina, Harvey shows how exposed the US energy sector remains to the risk of weather disruptions. As global warming raises the threat of catastrophic weather events, this vulnerability may be rising."

Ironically, since Katrina, the US oil industry has become more vulnerable to climate disasters, rather than less, buoyed by the shale boom.

"One of the unexpected consequences of the US shale boom is the rising co-vulnerability of its increasingly complex and integrated energy system", notes Halff: "Even inland plays such as the Permian, the shale industry's star performer, seemingly out of harm's way, have become exposed to the risk of weather disruptions at coastal refineries, pipelines and export facilities on which they depend for market access."

The US shale industry built that infrastructure knowing that its refineries and pipelines were vulnerable to climate disasters. But short term profit always wins.

Nearly half the country's refining capacity is in harm's way on the Gulf Coast. This capacity is vulnerable to storms, hurricanes and super-storms, all of which will become more frequent with climate change. The oil industry knew this. But they built anyway.

They also knew that their refineries would cause significant pollution if they were caught up in a super storm like Harvey. But they built anyway.

To give you just one small example. In an article for the New York Times last October, entitled "When the Next Hurricane Hits Texas", Roy Scranton, an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Notre Dame, wrote: "Imagine a hurricane ... aimed straight at the heart of the American petrochemical industry." In his article he named an imaginary Hurricane called Isaiah, which "crashes through refineries, chemical storage facilities, wharves and production plants" such as Exxon's Baytown refinery: "It's an imaginary calamity based on research and models. The bad news is that it's only a matter of time before it does."

And only a matter of time it was. It took less than a year for Harvey to hit.

At its height, Harvey caused eleven refineries to be shut down. As Zoe Schlanger explains on the Quartz website, when refineries are forced to shut down, "they often release far greater volumes of toxic air pollution than the normal legal limits would allow."

One of those was Exxon's Baytown, which "released about double the amount of volatile organic compounds--a broad category of air toxics--than its permit normally allows". Shell also shut down its Deer Park refinery, releasing excess amounts of the cancer causing chemical benzene, amongst others.

Schlanger adds: "In industry parlance, these pollution spikes are called 'exceptional events'. The excess pollution is considered an emergency necessity to prevent worse outcomes, like an explosion, so plants are exempt from fines they would ordinarily pay for exceeding their legal pollution limits." So the system allows the industry to poison the local population even more in times of trouble.

As Harvey's rain intensified, some refineries in the path of the storm began to flare excess chemicals, directly impacting the poorer, Latino communities in Houston's East End. At the height of the storm, the local communities were reporting strong gas and chemical-like smells. "I've been smelling them all night and off and on this morning," Bryan Parras, an activist at the grassroots environmental justice group TEJAS, from Housten's East End, told the New Republic.

Parras added said some residents were experiencing "headaches, sore throat, scratchy throat and itchy eyes." But due to the rising flood waters, the residents were trapped, breathing in the toxic air. "Fenceline communities can't leave or evacuate so they are literally getting gassed by these chemicals," Parras added.

Nor was it just refineries. The Associated Press has explored Harvey's impact on toxic Superfund sites, a legacy of the oil and gas industry, of which there are dozens in the Houston area.

The AP "surveyed seven Superfund sites in and around Houston during the flooding. All had been inundated with water, in some cases many feet deep". Later the Environmetnal Protection Agency would confirm that over a dozen sites had been damaged.

When the AP visited one site, San Jacinto River Waste Pits Superfund site, it was "completely covered with floodwaters ... The flow from the raging river washing over the toxic site was so intense it damaged an adjacent section of the Interstate 10 bridge ... There was no way to immediately assess how much contaminated soil from the site might have been washed away."

Then of course we have had the wide petrochemical plants, one of which exploded last week. The response from the company was to let it "burn itself out". Where, you might well ask, was the emergency plan to prevent this happening?

Two years ago, the local newspaper, The Houston Chronicle documented the total lax safety standards of the petrochemical industry in the state in a must-read eight-part series.

At the time, Ron White, the former director of regulatory policy at the Center for Effective Government, told the paper that "It will take another disaster" before the authorites started to reign in the petrochemical industry and take pre-emptive action.

That disaster has now happened. Now is the time to act. Before another storm hits.

Yesterday, the Governor of Texas warned that the bill for reconstruction after Superstorm Harvey could be as high as $180 billion. To put this into perspective, this is much worse that Hurricane Katrina.

It also does not include the hidden huge impact on local health and the environment from the toxic release of dozens of chemicals from the state's petrochemical infrastructure - from refineries, chemical plants to toxic pits.

Brock Long, the Head of the Government's Disaster Management Agency, also told CBS News that Harvey should be a wake-up call for local officials. "It is a wake-up call for this country for local and state elected officials to give their governors and their emergency management directors the full budgets that they need to be fully staffed, to design rainy-day funds, to have your own stand-alone individual assistance and public assistance programmes," he said.

The disaster should also be a wake-up call to the climate-denying President that unless he acts on climate, there will be more Harveys.

It is a wake-up call to the media to accurately report the disaster, including how climate change fuelled its intensity. It is also a wake-up call to the oil industry in so many, many ways.

On a national and international level it shows how our continuing dependence on fossil fuels will drive more extreme weather events. On a regional level it shows how ill-prepared the fossil fuel industry - and wider petrochemical industry - were to an event like this, despite decades of warnings.

Instead the fossil fuel industry's complacency, malaise, self-regulation and capture of the political system are all to blame too. They have led to a system of peril.

Antoine Halff is director of the Global Oil Markets Research Program at the Center on Global Energy Policy, at Columbia University, notes in the Financial Times: "Like Katrina, Harvey shows how exposed the US energy sector remains to the risk of weather disruptions. As global warming raises the threat of catastrophic weather events, this vulnerability may be rising."

Ironically, since Katrina, the US oil industry has become more vulnerable to climate disasters, rather than less, buoyed by the shale boom.

"One of the unexpected consequences of the US shale boom is the rising co-vulnerability of its increasingly complex and integrated energy system", notes Halff: "Even inland plays such as the Permian, the shale industry's star performer, seemingly out of harm's way, have become exposed to the risk of weather disruptions at coastal refineries, pipelines and export facilities on which they depend for market access."

The US shale industry built that infrastructure knowing that its refineries and pipelines were vulnerable to climate disasters. But short term profit always wins.

Nearly half the country's refining capacity is in harm's way on the Gulf Coast. This capacity is vulnerable to storms, hurricanes and super-storms, all of which will become more frequent with climate change. The oil industry knew this. But they built anyway.

They also knew that their refineries would cause significant pollution if they were caught up in a super storm like Harvey. But they built anyway.

To give you just one small example. In an article for the New York Times last October, entitled "When the Next Hurricane Hits Texas", Roy Scranton, an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Notre Dame, wrote: "Imagine a hurricane ... aimed straight at the heart of the American petrochemical industry." In his article he named an imaginary Hurricane called Isaiah, which "crashes through refineries, chemical storage facilities, wharves and production plants" such as Exxon's Baytown refinery: "It's an imaginary calamity based on research and models. The bad news is that it's only a matter of time before it does."

And only a matter of time it was. It took less than a year for Harvey to hit.

At its height, Harvey caused eleven refineries to be shut down. As Zoe Schlanger explains on the Quartz website, when refineries are forced to shut down, "they often release far greater volumes of toxic air pollution than the normal legal limits would allow."

One of those was Exxon's Baytown, which "released about double the amount of volatile organic compounds--a broad category of air toxics--than its permit normally allows". Shell also shut down its Deer Park refinery, releasing excess amounts of the cancer causing chemical benzene, amongst others.

Schlanger adds: "In industry parlance, these pollution spikes are called 'exceptional events'. The excess pollution is considered an emergency necessity to prevent worse outcomes, like an explosion, so plants are exempt from fines they would ordinarily pay for exceeding their legal pollution limits." So the system allows the industry to poison the local population even more in times of trouble.

As Harvey's rain intensified, some refineries in the path of the storm began to flare excess chemicals, directly impacting the poorer, Latino communities in Houston's East End. At the height of the storm, the local communities were reporting strong gas and chemical-like smells. "I've been smelling them all night and off and on this morning," Bryan Parras, an activist at the grassroots environmental justice group TEJAS, from Housten's East End, told the New Republic.

Parras added said some residents were experiencing "headaches, sore throat, scratchy throat and itchy eyes." But due to the rising flood waters, the residents were trapped, breathing in the toxic air. "Fenceline communities can't leave or evacuate so they are literally getting gassed by these chemicals," Parras added.

Nor was it just refineries. The Associated Press has explored Harvey's impact on toxic Superfund sites, a legacy of the oil and gas industry, of which there are dozens in the Houston area.

The AP "surveyed seven Superfund sites in and around Houston during the flooding. All had been inundated with water, in some cases many feet deep". Later the Environmetnal Protection Agency would confirm that over a dozen sites had been damaged.

When the AP visited one site, San Jacinto River Waste Pits Superfund site, it was "completely covered with floodwaters ... The flow from the raging river washing over the toxic site was so intense it damaged an adjacent section of the Interstate 10 bridge ... There was no way to immediately assess how much contaminated soil from the site might have been washed away."

Then of course we have had the wide petrochemical plants, one of which exploded last week. The response from the company was to let it "burn itself out". Where, you might well ask, was the emergency plan to prevent this happening?

Two years ago, the local newspaper, The Houston Chronicle documented the total lax safety standards of the petrochemical industry in the state in a must-read eight-part series.

At the time, Ron White, the former director of regulatory policy at the Center for Effective Government, told the paper that "It will take another disaster" before the authorites started to reign in the petrochemical industry and take pre-emptive action.

That disaster has now happened. Now is the time to act. Before another storm hits.