Scotland is over 9,000 km from Japan, but the two countries have something in common. You can find significant radioactive contamination from the other side of the world along the Scottish coastline, buried in riverbeds and mixed into the Irish Sea. Yes, radioactive contamination. From Japan.

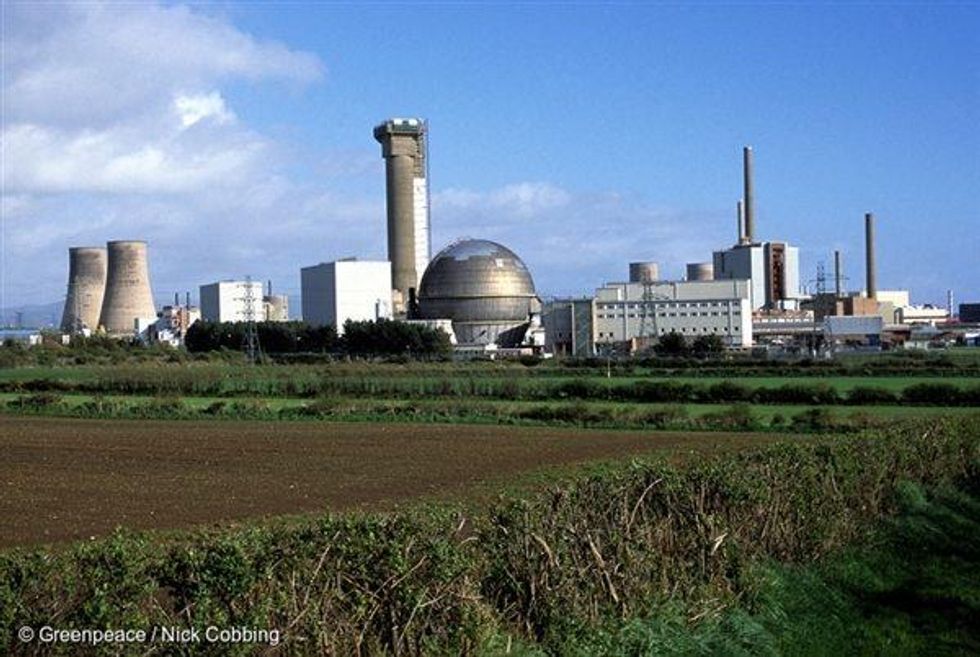

Since the 1970s, Sellafield, a nuclear-reprocessing plant in northwest England has been contracted to process high level nuclear waste spent fuel from Japanese reactors. More than 4000 tonnes of spent nuclear fuel was shipped from Japan to Sellafield, including waste from Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), the owner of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. As a result of reprocessing at Sellafield, more than 8 million liters of low-level nuclear waste is discharged into the ocean every day. It's been labeled the "most hazardous place in Europe" - with levels of contamination in the fields, soils, and estuaries at a level that can only be described as a nuclear disaster zone. The Irish Sea is arguably the most radioactively contaminated sea in the world.

We're about to approach the fifth anniversary of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, and this is a stark reminder that no matter where you are or how far away, nuclear power has a local and global impact.

I remember waking up to the news on March 11, 2011. Though I was at home in Scotland, I've never felt so connected to the people of Japan. Having spent decades with Greenpeace actively campaigning against nuclear power in Japan, I knew deep down that a catastrophic accident was only a matter of time. I recall appearing on BBC World News live with media requests coming in thick and fast. In mid-interview, as I was talking about the specific threat at Fukushima, I was interrupted as the news crossed to Japan, where Reactor 3 exploded.

Greenpeace Japan sent a team to the Fukushima evacuation zone to conduct independent radiation testing; and researchers on the Rainbow Warrior, kitted up in full body chemical suits, pulled floating seaweed from the surrounding area to use as samples. Our results were, unfortunately, as you would expect - high levels of contamination. Subsequently, we've also found radiation is still so widespread that it's unsafe for people to return across large parts of Fukushima.

Nearly five years later, I'm in Japan on board the Rainbow Warrior - this time with the famously anti-nuclear former Prime Minister of Japan, Mr. Naoto Kan. It's truly an honor and privilege to hear him describe the first hours and days of the accident in March 2011 and show him the research we are carrying out. The feelings were profound and surreal as we sailed within 2km of the nuclear plant. From the deck, we've seen steel tanks holding hundreds of thousands of tons of contaminated water; the four reactors now shielded behind temporary structures to contain some of the radioactive material from being released into the atmosphere; and inside the reactors, themselves lie hundreds of tons of molten reactor fuel for which there are no credible plans to deal with.

But there's another reason the Rainbow Warrior is here. A Greenpeace Japan research vessel is conducting underwater marine radiation surveys within a 20km radius of the Fukushima Daiichi plant, with the Rainbow Warrior acting as a campaign ship. As with the radioactive contamination near my home in Scotland, Greenpeace aims to further the understanding of the impacts and future threats from nuclear power, particularly the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident.

For Mr Naoto Kan, Japan's leader, when the disaster hit, this voyage was as personal as it was political. In the years since 2011, he has spoken out publicly against the nuclear industry, standing alongside millions of Japanese people opposed to nuclear power - a far cry from the current "tone-deaf" Abe administration, which is desperately trying to save a nuclear industry in crisis. Opposed by the majority of citizens and beset by enormous technical, financial, and legal obstacles, it's an effort that I believe is doomed to failure.

But there's hope.

Like the many communities across the country that are switching to innovative renewable power projects, Mr Kan knows that nuclear should be buried in the past. Renewables in Japan are rising. In the 2015 fiscal year, solar power capable of generating an estimated 13 TWh was newly installed - more than the two Sendai reactors in southern Japan that were restarted that year can produce.

For Japan to become 100% renewable, it must urgently formulate more ambitious targets, stop all planned investments in new coal power plants, finally abandon plans to restart its aging reactors and remove the institutional and financial obstacles to renewable energy growth.

A nuclear-free future is not only possible but essential. Renewable energy is the only safe and secure energy source for the people of Japan and the world.