"The media is biased," is a complaint that media organizations receive a lot, so they tend to be fairly wary of overtly partisan reporting. However, while media organizations are loath to seem partisan, they are often deeply unaware of other deep biases they hold.

One psychological bias humans suffer from is the "availability heuristic"--a tendency to generalize based on our immediate surroundings. It crops up in numerous ways: If you live in New York City, you might overestimate how many people commute by public transportation, since 40 percent of public transportation commuters in the whole country live in NYC. These biases certainly afflict newsrooms, which are whiter and more male than the general population and come from wealthier backgrounds. Most live in cities and live flight- and Uber-filled lives that simply don't comport with the lives of average Americans.

In other words, the media coverage has a distinctly upper-class bias. Case in point: the financial news of the last couple of days. Yesterday, when the Dow Jones dropped dramatically, news organizations were quick to report on the development. Twitter was ablaze with analysis and a new hashtag "Black Monday" was born (earning over 100,000 tweets when this article was written).

Yet fewer than half of Americans own stocks, and the top 10 percent richest Americans owned nearly 90 percent of all stocks, bonds, trusts and business equity in 2013 (see chart). Investment asset ownership is also divided across race lines, making up 17 percent of assets among non-Hispanic white households, but only 3.4 percent for black households and 2.5 percent for Hispanic households. For most Americans, the fact that wages for all but the richest 5 percent have fallen over the past seven years is a far more important story.

The media shapes our perceptions of reality. Americans who regularly consume Fox News coverage are more likely to express racial stereotypes and ignore structural racism. In a more complex academic analysis, Martin Gilens finds that in the early '90s, the media were far more likely to show African Americans when discussing the least sympathetic people in poverty (unemployed working age adults), and whites when discussing the most sympathetic poor (the elderly). He also finds that though African Americans make up a smaller portion of those in poverty, they are far more likely to be shown in coverage of the poor. This has led Americans to believe that those in poverty are overwhelmingly black, rather than white, as is the reality. The result was to racialize poverty, leading to reduced support among whites for anti-poverty programs.

The economy is no different: While the stock market has been humming along and corporate profits rebounded quickly, unemployment remains stubbornly high and wages low. At the same time, the recovery has been divided across racial lines, with the racial wealth gap in 2013 even larger than before the Great Recession. But news reports tend to downplay race gaps in unemployment, what Reniqua Allen calls the "permanent recession," focusing on the broad indicator. Newspapers and television anchors treat stock prices as though they are a symbol of broad prosperity, rather than a symbol that the rich are getting richer.

The New York Times Public Editor, Margaret Sullivan, acknowledged that the paper "does tend to go overboard sometimes" on how much it reports on the rich and famous. She does argue that "The Times does great work on subjects like homelessness, pay inequity, prison abuse and workers' rights." Undoubtedly true. But that doesn't change the fact that the paper moved the only reporter covering the race and ethnicity beat to cover the Bronx courthouse in January and created a new beat for TV critic Alessandra Stanley to new beat covering "the 1 percent of the 1 percent." Though the 1 percent of the 1 percent make up a tiny share of the population, they garner their own beat--those suffering under white supremacy or poverty will have to wait. The real question is not how meticulously newspapers scrutinize the richest 1 percent, but whether the project is worth embarking on at all.

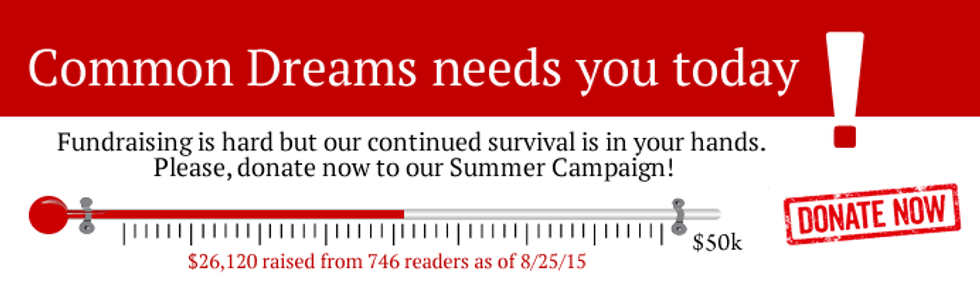

Newsrooms are increasingly squeezed by financial constraints, just like average Americans. Yet, newsrooms have still found the capacity to write more than 5,000 articles on Black Monday in the short seven hours since the Dow dropped. Imagine a world in which the stories that affect low-income and non-white Americans garnered the same news coverage as a bloop in the stock market. We'd hear a lot more about residential segregation, the racial wealth gap (single black and Latino women have one penny in wealth for every dollar a single white man has), and the fact that an increasing share of Americans have to rent-to-own their furniture at exorbitant interest rates. We'd be inundated by coverage about the fact that banks are buying up thousands of homes and renting them to people (often people of color, exacerbating the racial wealth gap), or that the richest 1 percent of Americans own more than one third of the wealth.

We'd know that the number of Americans living in concentrated poverty increased from 7.2 million to 12.8 million since 2000, or that teenage that teenage black high-school dropouts from poor families face a 95 percent unemployment rate. We'd know that 8 percent of Americans are unbanked (i.e. without a bank account), that the unbanked are disproportionately people of color and that they are vulnerable to exploitative banking practices like payday lending. We'd know that 1 in 5 American children live in poverty (40 percent of Black children and 1 in 3 Hispanic children).

The reality that writers and editors live in expensive cities on low salaries mean that it's more difficult for low-income people and people of color to break into the industry. However, editors should recognize that a racially and socioeconomically diverse newsroom would improve their ability to produce reportage that's more relatable to the lived experiences of average Americans. We should finance more journalism that's in the public interest, and thus freed from the constraints of advertisers.

But before anything can happen, editors and writers need to realize that their lived experience, and that of their friends and acquaintances, are different from those of many Americans. The rich have no problem getting their stories told--we need more stories from those whose voices aren't amplified.