SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

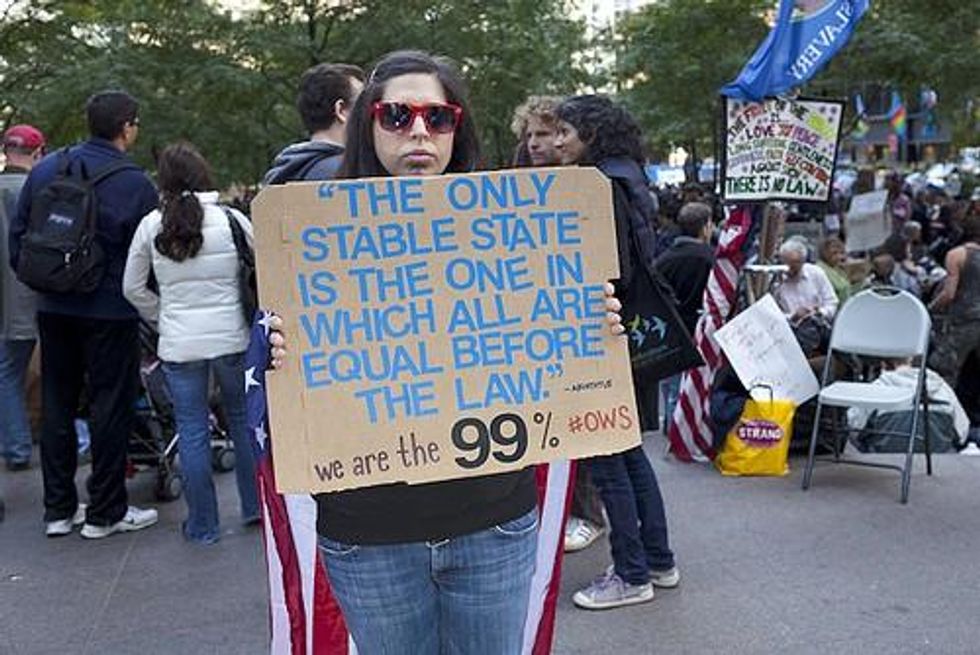

Some veterans of the Occupy and indignados movements are considering a turn towards electoral politics. This change of direction reflects an increasing awareness among activists that

Setting up political parties is not exactly what we have become accustomed to expect from radical activists. Yet, this is precisely what some of the participants in the last few years of protest and occupations are now busying themselves with. From Spain to the US, Greece to Turkey, many protesters have been persuaded that to do away with the 1% dominating the 99%, it will not be enough simply to resort to the heroic arsenal of street politics. After taking to squares, many now feel the time has come to occupy the state.

"We believed that, following the street protests, American democracy would have reacted by changing its way of doing things," Micah White, the former editor of the radical magazine Adbusters, credited with the invention of the name Occupy Wall Street, recently declared. "Now we are realising that you also have to win elections, and you have to govern, not just work against the government."

White's comments - which came after a meeting with Beppe Grillo, the leader of Italy's Five Star movement, the anti-austerity party that won 25% of the vote in the last general election - might appear as a shot in the dark. But elsewhere this electoral turn is already in full steam. Take the enigmatically named X party (Partido X), in Spain. This political formation has emerged out of a wing of the indignados movement, and is tipped to run in the European elections of 2014. Similar to the Five Star movement, the X party's platform centres on the promise of a new electronic democracy, that chimes very well with the desire for participation expressed in the occupied squares of 2011. Other activists connected with the occupation movement wave - in countries such as Israel, Turkey and Greece - are trying to open up more traditional left parties and to use them to continue where the street movements stopped.

It is not difficult to understand the reasons behind this new interest in electoral politics. The financial crisis of 2008 has brought about a tectonic shift in public opinion. A number of impressive results for left formations, from the great showing of Syriza in the 2012 Greek elections, to the recent victory of De Blasio in New York, and the election of student leader Camila Vallejo in Chile, have shown the extent to which the electorate is looking for radical progressive alternatives.

Naturally, not everybody within the occupation movement is buying into this strategy. Many continue to see the state as the source of all evil, and in electoral politics a manifestation of despicable reformism. Yet, having to confront on a daily basis a difficult economic situation that begs for fast and realistic solutions, many have come to view new forms of engagement with political institutions favourably.

If there is something that the financial crisis and austerity politics has taught us, it is that, for all the recurring predictions about its ultimate disappearance, the state continues to deeply influence our lives. We have learned that the provision of the public services we cherish the most - education, health, public parks - is largely dependent on decisions taken at state level. Naturally, it would be foolish, in a world of global capitalism, to think that once the state is occupied, one can do as one wishes. But why shouldn't we also use the state, to secure new universal rights - free health, free education, free transportation, decent housing for all - of the type that have been prefigured in the occupied squares of 2011?

Anti-globalisation activists believed that, as asserted by Marxist scholar John Holloway, we could "change the world without taking power". Many in the new generation of activists have become painfully aware that in order to achieve real change you also need to take power; that in order to really scare the 1%, you also need to occupy the state.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Some veterans of the Occupy and indignados movements are considering a turn towards electoral politics. This change of direction reflects an increasing awareness among activists that

Setting up political parties is not exactly what we have become accustomed to expect from radical activists. Yet, this is precisely what some of the participants in the last few years of protest and occupations are now busying themselves with. From Spain to the US, Greece to Turkey, many protesters have been persuaded that to do away with the 1% dominating the 99%, it will not be enough simply to resort to the heroic arsenal of street politics. After taking to squares, many now feel the time has come to occupy the state.

"We believed that, following the street protests, American democracy would have reacted by changing its way of doing things," Micah White, the former editor of the radical magazine Adbusters, credited with the invention of the name Occupy Wall Street, recently declared. "Now we are realising that you also have to win elections, and you have to govern, not just work against the government."

White's comments - which came after a meeting with Beppe Grillo, the leader of Italy's Five Star movement, the anti-austerity party that won 25% of the vote in the last general election - might appear as a shot in the dark. But elsewhere this electoral turn is already in full steam. Take the enigmatically named X party (Partido X), in Spain. This political formation has emerged out of a wing of the indignados movement, and is tipped to run in the European elections of 2014. Similar to the Five Star movement, the X party's platform centres on the promise of a new electronic democracy, that chimes very well with the desire for participation expressed in the occupied squares of 2011. Other activists connected with the occupation movement wave - in countries such as Israel, Turkey and Greece - are trying to open up more traditional left parties and to use them to continue where the street movements stopped.

It is not difficult to understand the reasons behind this new interest in electoral politics. The financial crisis of 2008 has brought about a tectonic shift in public opinion. A number of impressive results for left formations, from the great showing of Syriza in the 2012 Greek elections, to the recent victory of De Blasio in New York, and the election of student leader Camila Vallejo in Chile, have shown the extent to which the electorate is looking for radical progressive alternatives.

Naturally, not everybody within the occupation movement is buying into this strategy. Many continue to see the state as the source of all evil, and in electoral politics a manifestation of despicable reformism. Yet, having to confront on a daily basis a difficult economic situation that begs for fast and realistic solutions, many have come to view new forms of engagement with political institutions favourably.

If there is something that the financial crisis and austerity politics has taught us, it is that, for all the recurring predictions about its ultimate disappearance, the state continues to deeply influence our lives. We have learned that the provision of the public services we cherish the most - education, health, public parks - is largely dependent on decisions taken at state level. Naturally, it would be foolish, in a world of global capitalism, to think that once the state is occupied, one can do as one wishes. But why shouldn't we also use the state, to secure new universal rights - free health, free education, free transportation, decent housing for all - of the type that have been prefigured in the occupied squares of 2011?

Anti-globalisation activists believed that, as asserted by Marxist scholar John Holloway, we could "change the world without taking power". Many in the new generation of activists have become painfully aware that in order to achieve real change you also need to take power; that in order to really scare the 1%, you also need to occupy the state.

Some veterans of the Occupy and indignados movements are considering a turn towards electoral politics. This change of direction reflects an increasing awareness among activists that

Setting up political parties is not exactly what we have become accustomed to expect from radical activists. Yet, this is precisely what some of the participants in the last few years of protest and occupations are now busying themselves with. From Spain to the US, Greece to Turkey, many protesters have been persuaded that to do away with the 1% dominating the 99%, it will not be enough simply to resort to the heroic arsenal of street politics. After taking to squares, many now feel the time has come to occupy the state.

"We believed that, following the street protests, American democracy would have reacted by changing its way of doing things," Micah White, the former editor of the radical magazine Adbusters, credited with the invention of the name Occupy Wall Street, recently declared. "Now we are realising that you also have to win elections, and you have to govern, not just work against the government."

White's comments - which came after a meeting with Beppe Grillo, the leader of Italy's Five Star movement, the anti-austerity party that won 25% of the vote in the last general election - might appear as a shot in the dark. But elsewhere this electoral turn is already in full steam. Take the enigmatically named X party (Partido X), in Spain. This political formation has emerged out of a wing of the indignados movement, and is tipped to run in the European elections of 2014. Similar to the Five Star movement, the X party's platform centres on the promise of a new electronic democracy, that chimes very well with the desire for participation expressed in the occupied squares of 2011. Other activists connected with the occupation movement wave - in countries such as Israel, Turkey and Greece - are trying to open up more traditional left parties and to use them to continue where the street movements stopped.

It is not difficult to understand the reasons behind this new interest in electoral politics. The financial crisis of 2008 has brought about a tectonic shift in public opinion. A number of impressive results for left formations, from the great showing of Syriza in the 2012 Greek elections, to the recent victory of De Blasio in New York, and the election of student leader Camila Vallejo in Chile, have shown the extent to which the electorate is looking for radical progressive alternatives.

Naturally, not everybody within the occupation movement is buying into this strategy. Many continue to see the state as the source of all evil, and in electoral politics a manifestation of despicable reformism. Yet, having to confront on a daily basis a difficult economic situation that begs for fast and realistic solutions, many have come to view new forms of engagement with political institutions favourably.

If there is something that the financial crisis and austerity politics has taught us, it is that, for all the recurring predictions about its ultimate disappearance, the state continues to deeply influence our lives. We have learned that the provision of the public services we cherish the most - education, health, public parks - is largely dependent on decisions taken at state level. Naturally, it would be foolish, in a world of global capitalism, to think that once the state is occupied, one can do as one wishes. But why shouldn't we also use the state, to secure new universal rights - free health, free education, free transportation, decent housing for all - of the type that have been prefigured in the occupied squares of 2011?

Anti-globalisation activists believed that, as asserted by Marxist scholar John Holloway, we could "change the world without taking power". Many in the new generation of activists have become painfully aware that in order to achieve real change you also need to take power; that in order to really scare the 1%, you also need to occupy the state.