SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

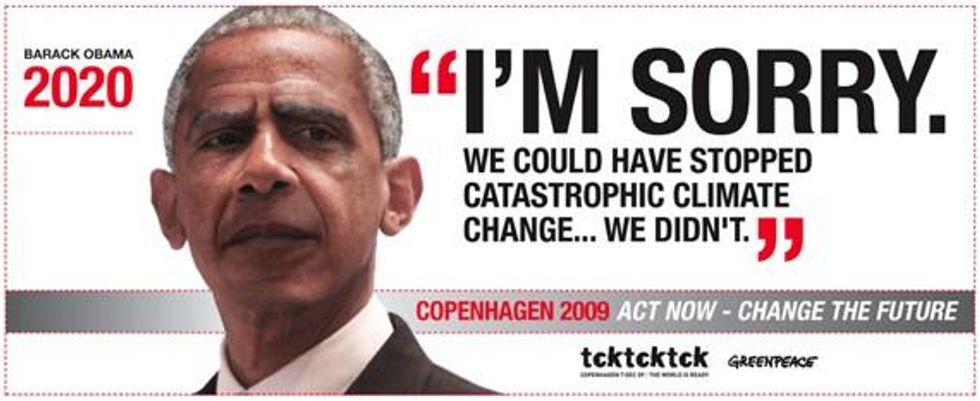

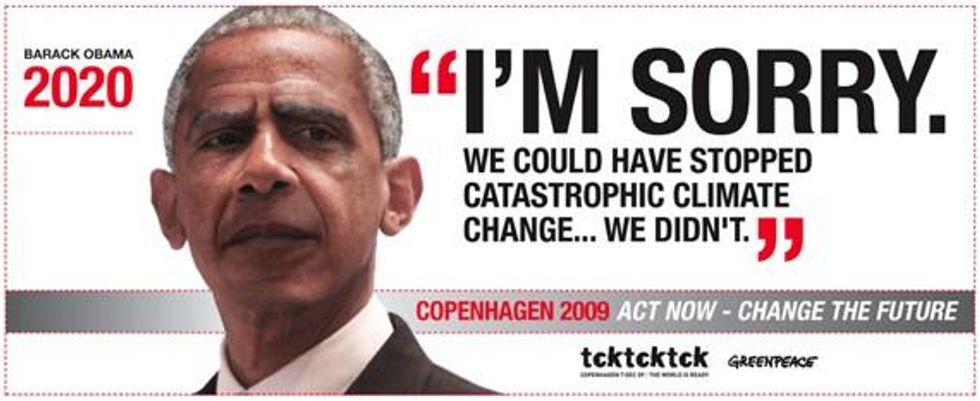

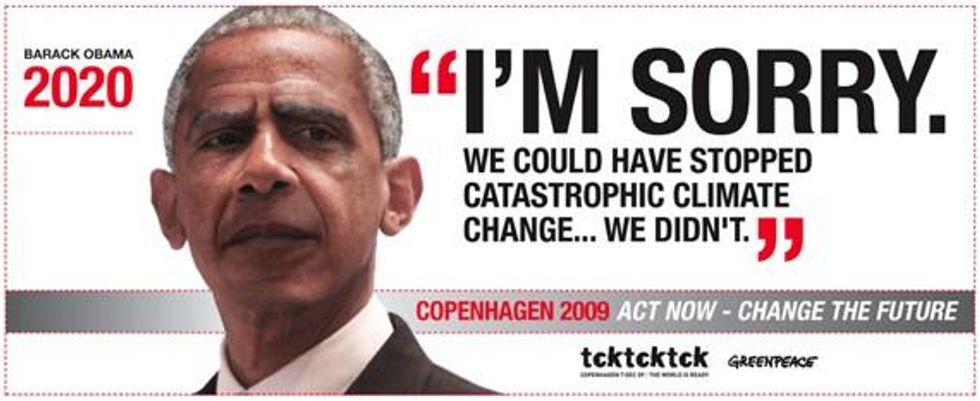

The more we hear calls for the urgency of climate justice like that of Bill McKibben's July Rolling Stone article, the more we confront a strategic dilemma: Where shall we put our energy, on the local or national level?

The U.S. presidential campaign going on now is a daily reminder of the vacuum on the national stage. The candidates think it wise to downplay climate change as an issue even though the actions (and non-actions) of the person in the Oval Office have large consequences. Obama, for example, has reportedly saved 70 Appalachian mountains from mountaintop removal coal mining -- earning ferocious hatred from Big Coal as a result. But he doesn't see the pragmatism in talking about it.

The national vacuum cries out for attention. We who prioritize local action, however, are wary. Many of us have encountered smoke-and-mirrors tactics at a national level that fail to build the mass base needed for major impact.

The easy answer is to say, "Both national and local levels need attention." It's much harder, however, to solve the practical problems of strategy and structure that make local and national levels work well together, and it's too late in the game for each of us simply to do our bit and hope that it all adds up. We need to go beyond addition to multiplication. We need a synergistic outcome from local and national work -- and international as well, but that's another column.

The good news is that activists in the past have faced the need for such synergy, and one solution they invented might work for us. But first we need a bit of historical context really to recognize what they accomplished.

From boycotts and sit-ins to a national movement

In the 1950s, civil rights activists faced a bleak situation. The anti-Communist crusade had scared most progressives into caution or inaction altogether. Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph and black radical pacifist Bayard Rustin were confident that mass nonviolent direct action could fuel massive change, but few agreed with them. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the largest civil rights organization in terms of credibility, resources and mass membership was cold to direct action, preferring lobbying and court litigation.

As Randolph and Rustin saw it, the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955 was the breakthrough, and they'd thought so much about strategy already that they were ready to move. Rustin was released by the War Resisters League to go to Montgomery to help out and coach the inexperienced Martin Luther King Jr. Following the victory in Montgomery, people in other Southern cities mounted other local actions -- mainly bus boycotts and sit-ins.

I knew Bayard Rustin, and one of his favorite expressions was "in motion"; now that Southern localities were in motion, supported by fundraising among Northern allies by Bayard, Ella Baker and others, Randolph and Rustin wanted to get the national level working to see what synergies they could generate.

The four tests

They came up with a series of three national marches on Washington that were carefully calibrated to: (a) get normally competitive groups working together (because unity is itself energy-creating), (b) focus on a civil rights issue where the federal government could do something even though it didn't want to, (c) provide opportunities for ever-greater outreach to potential allies, and (d) give local activists the experience of larger numbers and the inspiration to go home feeling empowered.

In the buttoned-down society of the 1950s -- someone called Americans of the day "God's frozen people" -- these marches were edgy. Today's marches are rarely worthwhile because they are decidedly un-edgy rituals, to the point of driving some radicals who recognize their pointlessness to destructive and counterproductive behavior.

But back then in 1957 the prospect of thousands of black people on a Prayer Pilgrimage to Washington filled President Dwight Eisenhower with alarm. As it turned out, Bayard organized the march so skillfully that all four tests were realized -- plus the bonus that King, through his oratory, transitioned from a local leader to a national one.

The 1958 and 1959 Youth Marches for Integrated Schools were reportedly the largest youth protests in Washington's history. The two events met all four tests so successfully that the NAACP's Roy Wilkins derailed his organization's planned follow-up lest his own strategy interfere with the strategy behind the marches. Young activists went back to their homes and campuses to dream and plan direct action.

On January 24, 1960, A. Philip Randolph issued "A Call for Immediate Mass Action" at a huge meeting at Carnegie Hall in New York. Eight days later, on February 1, four black students sat at a Greensboro, North Carolina, segregated lunch counter and asked for a cup of coffee. A wave of sit-ins spread across the South, followed shortly by Freedom Rides and mass action in dozens of locations.

Context matters hugely in tactical choices. The 1950s national-level actions, it turned out, were edgy enough to inspire people to do edgy local actions.

With the country swarming with local civil rights campaigns, and white resistance growing rapidly and violently, Randolph and Rustin saw the opportunity to return to the national level. President John Kennedy thought this was a dreadful idea and recommended that federal workers stay home on August 28, 1963, the day of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Presidents did not like masses of black people marching on Washington.

For Rustin and Randolph, though, the timing was especially good for their third strategic objective -- to push more allies to step up -- and this march drew a significant turnout from the largely white labor movement. The 1963 March on Washington thus widened the crack in racism sufficiently enough that federal action was taken that same year through the Birmingham, Alabama, campaign.

To impact Washington, go to Birmingham?

When President John Kennedy refused Martin Luther King, Jr.'s request that he take action for civil rights, King joined the Southern Christian Leadership Council affiliate in Birmingham, led by Fred Shuttlesworth, to escalate the struggle there. The result was globally televised images of white police and dogs and water hoses terrorizing black nonviolent demonstrators. Four young children were killed when a black church was bombed. The industrial city of Birmingham was, to use Rustin's phrase, in a state of social dislocation.

In the midst of crisis, Kennedy reportedly worked the phones with key industrial leaders and won agreement that a civil rights bill was needed. Lyndon Johnson managed the bill. The result was meaningful systemic intervention by the federal government: the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The daring 1963 local campaign that forced this national change showed the synergistic potential of working both levels at once. This kind of leverage was repeated two years later, when the Selma, Alabama, campaign catalyzed the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The choice to bring the conflict to a boil locally rather than in Washington, D.C., as the later Mayday anti-Vietnam war protests did, was highly strategic. The violence the protesters encountered in Birmingham and Selma had a much bigger impact in energizing allies and heightening the pressure on Washington than repression in the nation's capitol would have. It was also hugely important that behind the scenes of the local campaigns, organizers were building a base for making the strategy work on a national level.

Rustin, along with Ella Baker and others, built the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to an infrastructure for local-national synergy. Beginning as a grouping of ministers around King, then nurtured by the Prayer Pilgrimage and local programs, the organization developed some strong local chapters that led campaigns on their own. James Lawson, who coached the students who created the iconic Nashville, Tennessee, sit-in campaign, was sent there by the SCLC.

The SCLC developed a kind of power grid, one in which local campaigns that heated up and needed more resources could tap regional and national energy: seasoned organizers, money, additional volunteers to join direct action, King's charisma and a network of allies. We can learn from that.

Toward a nonviolent power grid for eco-justice

The time has come for the eco-justice movement to create a power grid connecting national resources with local nonviolent campaigns. The Rainforest Action Network and others have experimented in this direction. Tar sands and mountaintop removal coal mining are two of many issues that lend themselves to further development on both national and local levels.

The opportunity now is for organizers to channel the wisdom and daringness of Rustin and Randolph, to create national actions that meet the four tests, and grow an infrastructure that enables local campaigns to have national consequences.

The end of Peter Rugh's exciting article last week at Waging Nonviolence about the growing direct action against fossil fuels underlines the importance of strategizing a la Randolph and Rustin. Anti-fracking activist Sam Rubin poignantly describes what none of us want; he's worried that he'll be "just some guy in a bubble who only cares about my little issue."

His way of avoiding that isolation is to see himself as part of the global anti-capitalist struggle. Unfortunately, I don't think that helps us much in this country, at this moment in history.

What I learn from Rustin and Randolph is that there might be a more effective way to see oneself as part of a broader movement -- which is, well, to broaden it. Direct action, especially when it gives itself an ideological brand like "anti-capitalist," broadens movements in only rare political moments. I don't believe this is one of them.

What most often broadens movements is organizing. Organizers learn to speak the language of those they are connecting with -- in our case, people who are ambivalent in their analysis and vision but are daily becoming clearer about their interests. Saying "anti-capitalist" won't move them. Instead, build vehicles that bring together the radicals and those with direct anger and concern, and create events to seed the next wave of local direct actions. When they're all in one place, they'll lose any sense of isolation and futility that we may feel.

That's the lesson of what worked in the civil rights movement: direct action that was always related to organizing. One without the other can't build the power we need.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

George Lakey studied sociology at the University of Oslo and led workshops in other Nordic countries. He has published eleven books, including Viking Economics: How the Scandinavians got it right and how we can, too (Melville House paperback 2017). His most recent book is his memoir: Dancing with History: A Life for Peace and Justice (Seven Stories Press, 2022.

The U.S. presidential campaign going on now is a daily reminder of the vacuum on the national stage. The candidates think it wise to downplay climate change as an issue even though the actions (and non-actions) of the person in the Oval Office have large consequences. Obama, for example, has reportedly saved 70 Appalachian mountains from mountaintop removal coal mining -- earning ferocious hatred from Big Coal as a result. But he doesn't see the pragmatism in talking about it.

The national vacuum cries out for attention. We who prioritize local action, however, are wary. Many of us have encountered smoke-and-mirrors tactics at a national level that fail to build the mass base needed for major impact.

The easy answer is to say, "Both national and local levels need attention." It's much harder, however, to solve the practical problems of strategy and structure that make local and national levels work well together, and it's too late in the game for each of us simply to do our bit and hope that it all adds up. We need to go beyond addition to multiplication. We need a synergistic outcome from local and national work -- and international as well, but that's another column.

The good news is that activists in the past have faced the need for such synergy, and one solution they invented might work for us. But first we need a bit of historical context really to recognize what they accomplished.

From boycotts and sit-ins to a national movement

In the 1950s, civil rights activists faced a bleak situation. The anti-Communist crusade had scared most progressives into caution or inaction altogether. Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph and black radical pacifist Bayard Rustin were confident that mass nonviolent direct action could fuel massive change, but few agreed with them. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the largest civil rights organization in terms of credibility, resources and mass membership was cold to direct action, preferring lobbying and court litigation.

As Randolph and Rustin saw it, the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955 was the breakthrough, and they'd thought so much about strategy already that they were ready to move. Rustin was released by the War Resisters League to go to Montgomery to help out and coach the inexperienced Martin Luther King Jr. Following the victory in Montgomery, people in other Southern cities mounted other local actions -- mainly bus boycotts and sit-ins.

I knew Bayard Rustin, and one of his favorite expressions was "in motion"; now that Southern localities were in motion, supported by fundraising among Northern allies by Bayard, Ella Baker and others, Randolph and Rustin wanted to get the national level working to see what synergies they could generate.

The four tests

They came up with a series of three national marches on Washington that were carefully calibrated to: (a) get normally competitive groups working together (because unity is itself energy-creating), (b) focus on a civil rights issue where the federal government could do something even though it didn't want to, (c) provide opportunities for ever-greater outreach to potential allies, and (d) give local activists the experience of larger numbers and the inspiration to go home feeling empowered.

In the buttoned-down society of the 1950s -- someone called Americans of the day "God's frozen people" -- these marches were edgy. Today's marches are rarely worthwhile because they are decidedly un-edgy rituals, to the point of driving some radicals who recognize their pointlessness to destructive and counterproductive behavior.

But back then in 1957 the prospect of thousands of black people on a Prayer Pilgrimage to Washington filled President Dwight Eisenhower with alarm. As it turned out, Bayard organized the march so skillfully that all four tests were realized -- plus the bonus that King, through his oratory, transitioned from a local leader to a national one.

The 1958 and 1959 Youth Marches for Integrated Schools were reportedly the largest youth protests in Washington's history. The two events met all four tests so successfully that the NAACP's Roy Wilkins derailed his organization's planned follow-up lest his own strategy interfere with the strategy behind the marches. Young activists went back to their homes and campuses to dream and plan direct action.

On January 24, 1960, A. Philip Randolph issued "A Call for Immediate Mass Action" at a huge meeting at Carnegie Hall in New York. Eight days later, on February 1, four black students sat at a Greensboro, North Carolina, segregated lunch counter and asked for a cup of coffee. A wave of sit-ins spread across the South, followed shortly by Freedom Rides and mass action in dozens of locations.

Context matters hugely in tactical choices. The 1950s national-level actions, it turned out, were edgy enough to inspire people to do edgy local actions.

With the country swarming with local civil rights campaigns, and white resistance growing rapidly and violently, Randolph and Rustin saw the opportunity to return to the national level. President John Kennedy thought this was a dreadful idea and recommended that federal workers stay home on August 28, 1963, the day of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Presidents did not like masses of black people marching on Washington.

For Rustin and Randolph, though, the timing was especially good for their third strategic objective -- to push more allies to step up -- and this march drew a significant turnout from the largely white labor movement. The 1963 March on Washington thus widened the crack in racism sufficiently enough that federal action was taken that same year through the Birmingham, Alabama, campaign.

To impact Washington, go to Birmingham?

When President John Kennedy refused Martin Luther King, Jr.'s request that he take action for civil rights, King joined the Southern Christian Leadership Council affiliate in Birmingham, led by Fred Shuttlesworth, to escalate the struggle there. The result was globally televised images of white police and dogs and water hoses terrorizing black nonviolent demonstrators. Four young children were killed when a black church was bombed. The industrial city of Birmingham was, to use Rustin's phrase, in a state of social dislocation.

In the midst of crisis, Kennedy reportedly worked the phones with key industrial leaders and won agreement that a civil rights bill was needed. Lyndon Johnson managed the bill. The result was meaningful systemic intervention by the federal government: the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The daring 1963 local campaign that forced this national change showed the synergistic potential of working both levels at once. This kind of leverage was repeated two years later, when the Selma, Alabama, campaign catalyzed the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The choice to bring the conflict to a boil locally rather than in Washington, D.C., as the later Mayday anti-Vietnam war protests did, was highly strategic. The violence the protesters encountered in Birmingham and Selma had a much bigger impact in energizing allies and heightening the pressure on Washington than repression in the nation's capitol would have. It was also hugely important that behind the scenes of the local campaigns, organizers were building a base for making the strategy work on a national level.

Rustin, along with Ella Baker and others, built the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to an infrastructure for local-national synergy. Beginning as a grouping of ministers around King, then nurtured by the Prayer Pilgrimage and local programs, the organization developed some strong local chapters that led campaigns on their own. James Lawson, who coached the students who created the iconic Nashville, Tennessee, sit-in campaign, was sent there by the SCLC.

The SCLC developed a kind of power grid, one in which local campaigns that heated up and needed more resources could tap regional and national energy: seasoned organizers, money, additional volunteers to join direct action, King's charisma and a network of allies. We can learn from that.

Toward a nonviolent power grid for eco-justice

The time has come for the eco-justice movement to create a power grid connecting national resources with local nonviolent campaigns. The Rainforest Action Network and others have experimented in this direction. Tar sands and mountaintop removal coal mining are two of many issues that lend themselves to further development on both national and local levels.

The opportunity now is for organizers to channel the wisdom and daringness of Rustin and Randolph, to create national actions that meet the four tests, and grow an infrastructure that enables local campaigns to have national consequences.

The end of Peter Rugh's exciting article last week at Waging Nonviolence about the growing direct action against fossil fuels underlines the importance of strategizing a la Randolph and Rustin. Anti-fracking activist Sam Rubin poignantly describes what none of us want; he's worried that he'll be "just some guy in a bubble who only cares about my little issue."

His way of avoiding that isolation is to see himself as part of the global anti-capitalist struggle. Unfortunately, I don't think that helps us much in this country, at this moment in history.

What I learn from Rustin and Randolph is that there might be a more effective way to see oneself as part of a broader movement -- which is, well, to broaden it. Direct action, especially when it gives itself an ideological brand like "anti-capitalist," broadens movements in only rare political moments. I don't believe this is one of them.

What most often broadens movements is organizing. Organizers learn to speak the language of those they are connecting with -- in our case, people who are ambivalent in their analysis and vision but are daily becoming clearer about their interests. Saying "anti-capitalist" won't move them. Instead, build vehicles that bring together the radicals and those with direct anger and concern, and create events to seed the next wave of local direct actions. When they're all in one place, they'll lose any sense of isolation and futility that we may feel.

That's the lesson of what worked in the civil rights movement: direct action that was always related to organizing. One without the other can't build the power we need.

George Lakey studied sociology at the University of Oslo and led workshops in other Nordic countries. He has published eleven books, including Viking Economics: How the Scandinavians got it right and how we can, too (Melville House paperback 2017). His most recent book is his memoir: Dancing with History: A Life for Peace and Justice (Seven Stories Press, 2022.

The U.S. presidential campaign going on now is a daily reminder of the vacuum on the national stage. The candidates think it wise to downplay climate change as an issue even though the actions (and non-actions) of the person in the Oval Office have large consequences. Obama, for example, has reportedly saved 70 Appalachian mountains from mountaintop removal coal mining -- earning ferocious hatred from Big Coal as a result. But he doesn't see the pragmatism in talking about it.

The national vacuum cries out for attention. We who prioritize local action, however, are wary. Many of us have encountered smoke-and-mirrors tactics at a national level that fail to build the mass base needed for major impact.

The easy answer is to say, "Both national and local levels need attention." It's much harder, however, to solve the practical problems of strategy and structure that make local and national levels work well together, and it's too late in the game for each of us simply to do our bit and hope that it all adds up. We need to go beyond addition to multiplication. We need a synergistic outcome from local and national work -- and international as well, but that's another column.

The good news is that activists in the past have faced the need for such synergy, and one solution they invented might work for us. But first we need a bit of historical context really to recognize what they accomplished.

From boycotts and sit-ins to a national movement

In the 1950s, civil rights activists faced a bleak situation. The anti-Communist crusade had scared most progressives into caution or inaction altogether. Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph and black radical pacifist Bayard Rustin were confident that mass nonviolent direct action could fuel massive change, but few agreed with them. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the largest civil rights organization in terms of credibility, resources and mass membership was cold to direct action, preferring lobbying and court litigation.

As Randolph and Rustin saw it, the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955 was the breakthrough, and they'd thought so much about strategy already that they were ready to move. Rustin was released by the War Resisters League to go to Montgomery to help out and coach the inexperienced Martin Luther King Jr. Following the victory in Montgomery, people in other Southern cities mounted other local actions -- mainly bus boycotts and sit-ins.

I knew Bayard Rustin, and one of his favorite expressions was "in motion"; now that Southern localities were in motion, supported by fundraising among Northern allies by Bayard, Ella Baker and others, Randolph and Rustin wanted to get the national level working to see what synergies they could generate.

The four tests

They came up with a series of three national marches on Washington that were carefully calibrated to: (a) get normally competitive groups working together (because unity is itself energy-creating), (b) focus on a civil rights issue where the federal government could do something even though it didn't want to, (c) provide opportunities for ever-greater outreach to potential allies, and (d) give local activists the experience of larger numbers and the inspiration to go home feeling empowered.

In the buttoned-down society of the 1950s -- someone called Americans of the day "God's frozen people" -- these marches were edgy. Today's marches are rarely worthwhile because they are decidedly un-edgy rituals, to the point of driving some radicals who recognize their pointlessness to destructive and counterproductive behavior.

But back then in 1957 the prospect of thousands of black people on a Prayer Pilgrimage to Washington filled President Dwight Eisenhower with alarm. As it turned out, Bayard organized the march so skillfully that all four tests were realized -- plus the bonus that King, through his oratory, transitioned from a local leader to a national one.

The 1958 and 1959 Youth Marches for Integrated Schools were reportedly the largest youth protests in Washington's history. The two events met all four tests so successfully that the NAACP's Roy Wilkins derailed his organization's planned follow-up lest his own strategy interfere with the strategy behind the marches. Young activists went back to their homes and campuses to dream and plan direct action.

On January 24, 1960, A. Philip Randolph issued "A Call for Immediate Mass Action" at a huge meeting at Carnegie Hall in New York. Eight days later, on February 1, four black students sat at a Greensboro, North Carolina, segregated lunch counter and asked for a cup of coffee. A wave of sit-ins spread across the South, followed shortly by Freedom Rides and mass action in dozens of locations.

Context matters hugely in tactical choices. The 1950s national-level actions, it turned out, were edgy enough to inspire people to do edgy local actions.

With the country swarming with local civil rights campaigns, and white resistance growing rapidly and violently, Randolph and Rustin saw the opportunity to return to the national level. President John Kennedy thought this was a dreadful idea and recommended that federal workers stay home on August 28, 1963, the day of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Presidents did not like masses of black people marching on Washington.

For Rustin and Randolph, though, the timing was especially good for their third strategic objective -- to push more allies to step up -- and this march drew a significant turnout from the largely white labor movement. The 1963 March on Washington thus widened the crack in racism sufficiently enough that federal action was taken that same year through the Birmingham, Alabama, campaign.

To impact Washington, go to Birmingham?

When President John Kennedy refused Martin Luther King, Jr.'s request that he take action for civil rights, King joined the Southern Christian Leadership Council affiliate in Birmingham, led by Fred Shuttlesworth, to escalate the struggle there. The result was globally televised images of white police and dogs and water hoses terrorizing black nonviolent demonstrators. Four young children were killed when a black church was bombed. The industrial city of Birmingham was, to use Rustin's phrase, in a state of social dislocation.

In the midst of crisis, Kennedy reportedly worked the phones with key industrial leaders and won agreement that a civil rights bill was needed. Lyndon Johnson managed the bill. The result was meaningful systemic intervention by the federal government: the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The daring 1963 local campaign that forced this national change showed the synergistic potential of working both levels at once. This kind of leverage was repeated two years later, when the Selma, Alabama, campaign catalyzed the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The choice to bring the conflict to a boil locally rather than in Washington, D.C., as the later Mayday anti-Vietnam war protests did, was highly strategic. The violence the protesters encountered in Birmingham and Selma had a much bigger impact in energizing allies and heightening the pressure on Washington than repression in the nation's capitol would have. It was also hugely important that behind the scenes of the local campaigns, organizers were building a base for making the strategy work on a national level.

Rustin, along with Ella Baker and others, built the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to an infrastructure for local-national synergy. Beginning as a grouping of ministers around King, then nurtured by the Prayer Pilgrimage and local programs, the organization developed some strong local chapters that led campaigns on their own. James Lawson, who coached the students who created the iconic Nashville, Tennessee, sit-in campaign, was sent there by the SCLC.

The SCLC developed a kind of power grid, one in which local campaigns that heated up and needed more resources could tap regional and national energy: seasoned organizers, money, additional volunteers to join direct action, King's charisma and a network of allies. We can learn from that.

Toward a nonviolent power grid for eco-justice

The time has come for the eco-justice movement to create a power grid connecting national resources with local nonviolent campaigns. The Rainforest Action Network and others have experimented in this direction. Tar sands and mountaintop removal coal mining are two of many issues that lend themselves to further development on both national and local levels.

The opportunity now is for organizers to channel the wisdom and daringness of Rustin and Randolph, to create national actions that meet the four tests, and grow an infrastructure that enables local campaigns to have national consequences.

The end of Peter Rugh's exciting article last week at Waging Nonviolence about the growing direct action against fossil fuels underlines the importance of strategizing a la Randolph and Rustin. Anti-fracking activist Sam Rubin poignantly describes what none of us want; he's worried that he'll be "just some guy in a bubble who only cares about my little issue."

His way of avoiding that isolation is to see himself as part of the global anti-capitalist struggle. Unfortunately, I don't think that helps us much in this country, at this moment in history.

What I learn from Rustin and Randolph is that there might be a more effective way to see oneself as part of a broader movement -- which is, well, to broaden it. Direct action, especially when it gives itself an ideological brand like "anti-capitalist," broadens movements in only rare political moments. I don't believe this is one of them.

What most often broadens movements is organizing. Organizers learn to speak the language of those they are connecting with -- in our case, people who are ambivalent in their analysis and vision but are daily becoming clearer about their interests. Saying "anti-capitalist" won't move them. Instead, build vehicles that bring together the radicals and those with direct anger and concern, and create events to seed the next wave of local direct actions. When they're all in one place, they'll lose any sense of isolation and futility that we may feel.

That's the lesson of what worked in the civil rights movement: direct action that was always related to organizing. One without the other can't build the power we need.