SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

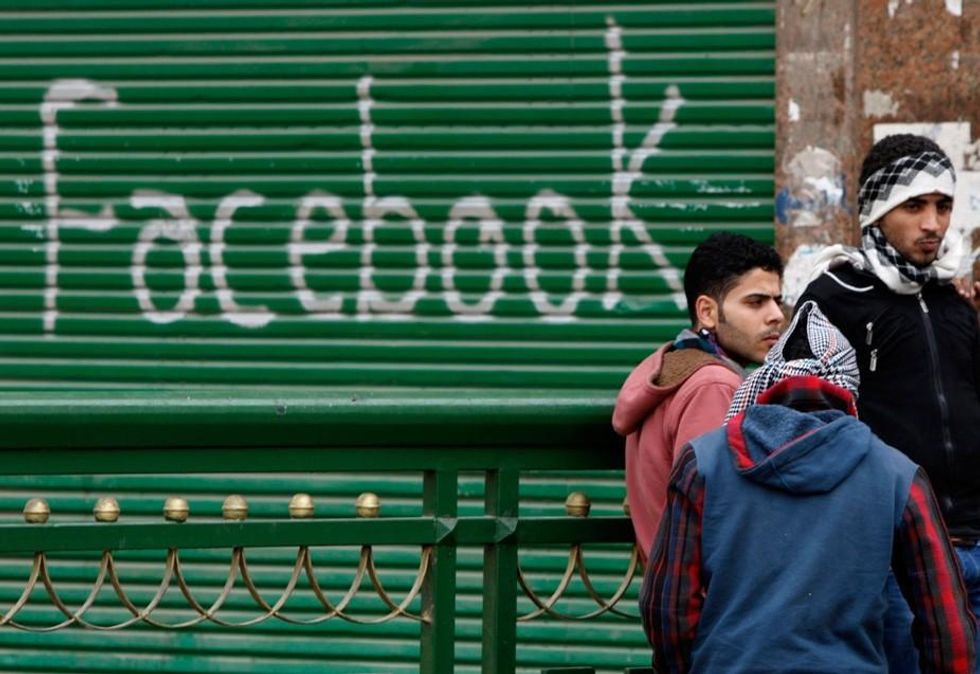

Remember the heady days of the Arab spring? People in motion. Democracy breaking out all over. And right in the middle of everything... Facebook!

Activists in Cairo's Tahrir Square, we marveled, were using Facebook and other social media tools to link and share and grow their movement. In a Facebook electronic age, anything suddenly seemed possible. A new world beckoned. A new world gloriously liberated from greed and corruption.

How's that new world coming, over a year later? That depends where you look.

Over in Egypt, voters are going to the polls this week to start a two-round presidential election contest, the first presidential balloting since Tahrir Square first captured the world's political imagination.

Egypt's eventual future still remains hazy. But the nation's struggle for economic justice and democracy has kept moving forward over the last year. Egyptians are continuing to break new political ground, most particularly on the bold notion of a "maximum wage," the idea that democracy and social decency both demand a limit on the income any one person can grab in a year.

The demand for a maximum wage in Egypt first surfaced in the militant labor protests that paved the way for last year's uprising in Tahrir Square. This maximum wage demand has now gone mainstream. In the current presidential race, almost all the prime contenders are endorsing a "maximum wage" ethic.

The candidates, to be sure, do differ on the "maximum wage" specifics.

Aboul Fotouh, a liberal Islamist candidate, wants a maximum wage applied only to the public sector, and the Egyptian parliament is now putting the finishing touches on legislation that would do just that. The pending bill would set a public sector maximum at 35 times a public enterprise's lowest wage, with an absolute income cap at the equivalent of just under $100,000 a year.

This public sector maximum would have a broad economic impact. In Egypt, the public sector covers nearly a quarter of the entire economy, not just government agencies but huge swatches of commercial and banking activity as well.

Activists from the Egyptian labor movement are calling for an even broader maximum wage. They're urging a maximum applied to the entire economy, public and private sector alike, and former Arab League secretary general Amr Moussa, the presidential front-runner, appears to be backing that position.

In Egypt, the presidential campaigning suggests, a new world that pushes back against greed does still beckon.

On the other hand, here in the United States, the movers and shakers behind the Facebook phenomenon that meant so much for the initial Arab spring are shoving Americans in an entirely different direction.

These Facebook kingpins haven't been challenging greed. They've been feting it, via an elaborately orchestrated initial public offering last week on Wall Street that dangled out to America's investing class juicy new fantasies of over-the-top speculative windfalls.

In the days leading up to last week's Facebook IPO, investors buzzed with that old "irrational exuberance" of the 1990s dot-com bubble. Stocks typically trade at $14 of share price value for every $1 of profit. Facebook went to market asking over $100 for every $1 of profit.

And the market went along, in the process kindling get-rich fever and, on Friday, minting instant billionaires within Facebook's inner circle.

One of those instant billionaires -- Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin -- took his money and ran. Saverin renounced his U.S. citizenship before the IPO. His move may enable him to avoid as much as $700 million in federal taxes.

The rest of the Facebook insider crew is staying put, at least for the moment, and doing its tax avoiding from the comfort of home.

Facebook's top dog, Mark Zuckerberg, announced before Friday's IPO that he would be exercising half the 120 million stock options he awarded himself in 2005. That decision cleared him a personal payday Friday around $2.3 billion.

The Facebook shares that Zuckerberg is still holding give him a net worth over $19 billion, and the 28-year-old seems to have no intention of sharing much of his new wealth with Uncle Sam.

The Wall Street Journal earlier this month detailed the tax code loophole -- the "grantor-retained annuity trust" -- that Zuckerberg and his fellow Facebook execs are likely using "to avoid at least $200 million of estate and gift taxes."

Facebook is avoiding enormously more than this $200 million at the enterprise level, thanks to the U.S. tax code's incredibly generous treatment of stock options. Facebook's exploitation of this option loophole, Citizens for Tax Justice calculates, will cost the federal and state governments about $6.4 billion.

How does this option loophole operate? Say Facebook hands out to execs a million options each to buy Facebook shares at $1 a share. These lucky option recipients later "exercise" their options and buy those shares at that $1 -- and then turn around and sell them at $38, the Facebook going rate last Friday.

These option recipients will have to pay income tax on their $37-per-share profit. But Facebook -- as an enterprise -- can deduct that $37 off its corporate income tax. This deduction, of course, will fatten Facebook's bottom line and pump up even further the value of the shares Facebook's execs are holding.

The pushback against all this Facebook greed grabbing?

In Washington last week, two U.S. senators -- Chuck Schumer from New York and Bob Casey from Pennsylvania -- did propose legislation that would subject future wealthy citizenship renouncers like Eduardo Saverin to a 30 percent capital gains tax rate. But even the bill's supporters acknowledge that this legislation has no chance whatsoever of passage in the current Congress.

Legislation from Michigan senator Carl Levin that would strike down the much more significant stock option loophole faces an equally steep path to passage. New York's Working Families Party, among other groups, is helping drive an effort to boost the Levin legislation.

Meanwhile, Fox Business News reported Friday that execs and investors who've "scored famously" from Facebook's Wall Street debut have multi-million dollar mansions and $100,000 Porsches "flying off local shelves" in Silicon Valley.

America's rich certainly do have cause to celebrate. But few people elsewhere in the world figure to be celebrating with them. For directions to a new world, they'll be better off looking toward Cairo.

This article originally appeared in Too Much, a weekly newsletter on excess and inequality published by the Institute for Policy Studies.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Remember the heady days of the Arab spring? People in motion. Democracy breaking out all over. And right in the middle of everything... Facebook!

Activists in Cairo's Tahrir Square, we marveled, were using Facebook and other social media tools to link and share and grow their movement. In a Facebook electronic age, anything suddenly seemed possible. A new world beckoned. A new world gloriously liberated from greed and corruption.

How's that new world coming, over a year later? That depends where you look.

Over in Egypt, voters are going to the polls this week to start a two-round presidential election contest, the first presidential balloting since Tahrir Square first captured the world's political imagination.

Egypt's eventual future still remains hazy. But the nation's struggle for economic justice and democracy has kept moving forward over the last year. Egyptians are continuing to break new political ground, most particularly on the bold notion of a "maximum wage," the idea that democracy and social decency both demand a limit on the income any one person can grab in a year.

The demand for a maximum wage in Egypt first surfaced in the militant labor protests that paved the way for last year's uprising in Tahrir Square. This maximum wage demand has now gone mainstream. In the current presidential race, almost all the prime contenders are endorsing a "maximum wage" ethic.

The candidates, to be sure, do differ on the "maximum wage" specifics.

Aboul Fotouh, a liberal Islamist candidate, wants a maximum wage applied only to the public sector, and the Egyptian parliament is now putting the finishing touches on legislation that would do just that. The pending bill would set a public sector maximum at 35 times a public enterprise's lowest wage, with an absolute income cap at the equivalent of just under $100,000 a year.

This public sector maximum would have a broad economic impact. In Egypt, the public sector covers nearly a quarter of the entire economy, not just government agencies but huge swatches of commercial and banking activity as well.

Activists from the Egyptian labor movement are calling for an even broader maximum wage. They're urging a maximum applied to the entire economy, public and private sector alike, and former Arab League secretary general Amr Moussa, the presidential front-runner, appears to be backing that position.

In Egypt, the presidential campaigning suggests, a new world that pushes back against greed does still beckon.

On the other hand, here in the United States, the movers and shakers behind the Facebook phenomenon that meant so much for the initial Arab spring are shoving Americans in an entirely different direction.

These Facebook kingpins haven't been challenging greed. They've been feting it, via an elaborately orchestrated initial public offering last week on Wall Street that dangled out to America's investing class juicy new fantasies of over-the-top speculative windfalls.

In the days leading up to last week's Facebook IPO, investors buzzed with that old "irrational exuberance" of the 1990s dot-com bubble. Stocks typically trade at $14 of share price value for every $1 of profit. Facebook went to market asking over $100 for every $1 of profit.

And the market went along, in the process kindling get-rich fever and, on Friday, minting instant billionaires within Facebook's inner circle.

One of those instant billionaires -- Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin -- took his money and ran. Saverin renounced his U.S. citizenship before the IPO. His move may enable him to avoid as much as $700 million in federal taxes.

The rest of the Facebook insider crew is staying put, at least for the moment, and doing its tax avoiding from the comfort of home.

Facebook's top dog, Mark Zuckerberg, announced before Friday's IPO that he would be exercising half the 120 million stock options he awarded himself in 2005. That decision cleared him a personal payday Friday around $2.3 billion.

The Facebook shares that Zuckerberg is still holding give him a net worth over $19 billion, and the 28-year-old seems to have no intention of sharing much of his new wealth with Uncle Sam.

The Wall Street Journal earlier this month detailed the tax code loophole -- the "grantor-retained annuity trust" -- that Zuckerberg and his fellow Facebook execs are likely using "to avoid at least $200 million of estate and gift taxes."

Facebook is avoiding enormously more than this $200 million at the enterprise level, thanks to the U.S. tax code's incredibly generous treatment of stock options. Facebook's exploitation of this option loophole, Citizens for Tax Justice calculates, will cost the federal and state governments about $6.4 billion.

How does this option loophole operate? Say Facebook hands out to execs a million options each to buy Facebook shares at $1 a share. These lucky option recipients later "exercise" their options and buy those shares at that $1 -- and then turn around and sell them at $38, the Facebook going rate last Friday.

These option recipients will have to pay income tax on their $37-per-share profit. But Facebook -- as an enterprise -- can deduct that $37 off its corporate income tax. This deduction, of course, will fatten Facebook's bottom line and pump up even further the value of the shares Facebook's execs are holding.

The pushback against all this Facebook greed grabbing?

In Washington last week, two U.S. senators -- Chuck Schumer from New York and Bob Casey from Pennsylvania -- did propose legislation that would subject future wealthy citizenship renouncers like Eduardo Saverin to a 30 percent capital gains tax rate. But even the bill's supporters acknowledge that this legislation has no chance whatsoever of passage in the current Congress.

Legislation from Michigan senator Carl Levin that would strike down the much more significant stock option loophole faces an equally steep path to passage. New York's Working Families Party, among other groups, is helping drive an effort to boost the Levin legislation.

Meanwhile, Fox Business News reported Friday that execs and investors who've "scored famously" from Facebook's Wall Street debut have multi-million dollar mansions and $100,000 Porsches "flying off local shelves" in Silicon Valley.

America's rich certainly do have cause to celebrate. But few people elsewhere in the world figure to be celebrating with them. For directions to a new world, they'll be better off looking toward Cairo.

This article originally appeared in Too Much, a weekly newsletter on excess and inequality published by the Institute for Policy Studies.

Remember the heady days of the Arab spring? People in motion. Democracy breaking out all over. And right in the middle of everything... Facebook!

Activists in Cairo's Tahrir Square, we marveled, were using Facebook and other social media tools to link and share and grow their movement. In a Facebook electronic age, anything suddenly seemed possible. A new world beckoned. A new world gloriously liberated from greed and corruption.

How's that new world coming, over a year later? That depends where you look.

Over in Egypt, voters are going to the polls this week to start a two-round presidential election contest, the first presidential balloting since Tahrir Square first captured the world's political imagination.

Egypt's eventual future still remains hazy. But the nation's struggle for economic justice and democracy has kept moving forward over the last year. Egyptians are continuing to break new political ground, most particularly on the bold notion of a "maximum wage," the idea that democracy and social decency both demand a limit on the income any one person can grab in a year.

The demand for a maximum wage in Egypt first surfaced in the militant labor protests that paved the way for last year's uprising in Tahrir Square. This maximum wage demand has now gone mainstream. In the current presidential race, almost all the prime contenders are endorsing a "maximum wage" ethic.

The candidates, to be sure, do differ on the "maximum wage" specifics.

Aboul Fotouh, a liberal Islamist candidate, wants a maximum wage applied only to the public sector, and the Egyptian parliament is now putting the finishing touches on legislation that would do just that. The pending bill would set a public sector maximum at 35 times a public enterprise's lowest wage, with an absolute income cap at the equivalent of just under $100,000 a year.

This public sector maximum would have a broad economic impact. In Egypt, the public sector covers nearly a quarter of the entire economy, not just government agencies but huge swatches of commercial and banking activity as well.

Activists from the Egyptian labor movement are calling for an even broader maximum wage. They're urging a maximum applied to the entire economy, public and private sector alike, and former Arab League secretary general Amr Moussa, the presidential front-runner, appears to be backing that position.

In Egypt, the presidential campaigning suggests, a new world that pushes back against greed does still beckon.

On the other hand, here in the United States, the movers and shakers behind the Facebook phenomenon that meant so much for the initial Arab spring are shoving Americans in an entirely different direction.

These Facebook kingpins haven't been challenging greed. They've been feting it, via an elaborately orchestrated initial public offering last week on Wall Street that dangled out to America's investing class juicy new fantasies of over-the-top speculative windfalls.

In the days leading up to last week's Facebook IPO, investors buzzed with that old "irrational exuberance" of the 1990s dot-com bubble. Stocks typically trade at $14 of share price value for every $1 of profit. Facebook went to market asking over $100 for every $1 of profit.

And the market went along, in the process kindling get-rich fever and, on Friday, minting instant billionaires within Facebook's inner circle.

One of those instant billionaires -- Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin -- took his money and ran. Saverin renounced his U.S. citizenship before the IPO. His move may enable him to avoid as much as $700 million in federal taxes.

The rest of the Facebook insider crew is staying put, at least for the moment, and doing its tax avoiding from the comfort of home.

Facebook's top dog, Mark Zuckerberg, announced before Friday's IPO that he would be exercising half the 120 million stock options he awarded himself in 2005. That decision cleared him a personal payday Friday around $2.3 billion.

The Facebook shares that Zuckerberg is still holding give him a net worth over $19 billion, and the 28-year-old seems to have no intention of sharing much of his new wealth with Uncle Sam.

The Wall Street Journal earlier this month detailed the tax code loophole -- the "grantor-retained annuity trust" -- that Zuckerberg and his fellow Facebook execs are likely using "to avoid at least $200 million of estate and gift taxes."

Facebook is avoiding enormously more than this $200 million at the enterprise level, thanks to the U.S. tax code's incredibly generous treatment of stock options. Facebook's exploitation of this option loophole, Citizens for Tax Justice calculates, will cost the federal and state governments about $6.4 billion.

How does this option loophole operate? Say Facebook hands out to execs a million options each to buy Facebook shares at $1 a share. These lucky option recipients later "exercise" their options and buy those shares at that $1 -- and then turn around and sell them at $38, the Facebook going rate last Friday.

These option recipients will have to pay income tax on their $37-per-share profit. But Facebook -- as an enterprise -- can deduct that $37 off its corporate income tax. This deduction, of course, will fatten Facebook's bottom line and pump up even further the value of the shares Facebook's execs are holding.

The pushback against all this Facebook greed grabbing?

In Washington last week, two U.S. senators -- Chuck Schumer from New York and Bob Casey from Pennsylvania -- did propose legislation that would subject future wealthy citizenship renouncers like Eduardo Saverin to a 30 percent capital gains tax rate. But even the bill's supporters acknowledge that this legislation has no chance whatsoever of passage in the current Congress.

Legislation from Michigan senator Carl Levin that would strike down the much more significant stock option loophole faces an equally steep path to passage. New York's Working Families Party, among other groups, is helping drive an effort to boost the Levin legislation.

Meanwhile, Fox Business News reported Friday that execs and investors who've "scored famously" from Facebook's Wall Street debut have multi-million dollar mansions and $100,000 Porsches "flying off local shelves" in Silicon Valley.

America's rich certainly do have cause to celebrate. But few people elsewhere in the world figure to be celebrating with them. For directions to a new world, they'll be better off looking toward Cairo.

This article originally appeared in Too Much, a weekly newsletter on excess and inequality published by the Institute for Policy Studies.