SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

As Somalia sank deeper into famine in late summer, with 63 percent of southern Somalia's population at risk of starvation, U.S. media coverage focused on stories of misery and resilience. Measuring children's emaciated arms and describing the scraps of dignity people struggled to maintain in refugee camps substituted for investigation of causes, or discussion of remedies beyond appeals for donations.

As Somalia sank deeper into famine in late summer, with 63 percent of southern Somalia's population at risk of starvation, U.S. media coverage focused on stories of misery and resilience. Measuring children's emaciated arms and describing the scraps of dignity people struggled to maintain in refugee camps substituted for investigation of causes, or discussion of remedies beyond appeals for donations.

A typical report came from CBS Evening News (8/8/11): "The faces dusted with the desert and...the eyes that have seen too much," with an interview with a woman "who had fought to save her children in an unforgiving land." The next day (8/9/11), the network brought us "people with lessons to teach about life and death in an unforgiving land."

While drought can be a natural phenomenon, famine in the modern era is political--and avoidable. A variety of factors play into the current Somalia famine, but media could only seem to find one culprit: Islamic terrorists. Al-Shabaab, the militant youth group that controls much of Somalia and has been labeled a terrorist organization by the U.S. government, "is widely blamed for causing a famine in Somalia by forcing out many Western aid organizations," explained the New York Times (8/2/11).

And nearly all of the rest of the media agreed. "Terror Group Blocking Aid to Three Million Starving Somalis" blared a USA Today headline (8/15/11). "The spread of Islamic terrorism has turned a drought into a famine that didn't have to happen," reported NBC Nightly News' Ann Curry (8/16/11) from Mogadishu. Curry's colleague Richard Engel (NBC, 8/5/11) argued earlier: "But what may be most tragic of all, the famine here is largely man-made. Somalia is a failed state and a war zone. Peacekeepers from Uganda and Burundi are fighting to drive out Al-Qaeda backed militants called Al-Shabaab. The militants control half the country."

While Al-Shabaab certainly bears responsibility for any of its actions that prevented food from reaching people in need, other major pieces are missing from this story of man-made disaster--including climate change, agricultural policy and the history of U.S. foreign policy in Somalia.

Scientists have long warned that a warming planet would lead to more dramatic weather patterns, including droughts. And in recent years, drought has hit the Horn of Africa much more frequently than the historical average (Guardian, 8/8/11). On prominent TV news programs, though, climate change simply wasn't considered in reports on Somalia's famine. In newspapers, climate change was relegated almost exclusively to opinion pages, either in print (e.g., San Francisco Chronicle, 7/23/11; Baltimore Sun, 8/1/11) or web-only (e.g., New York Times Dot Earth Blog, 8/3/11).

While Al-Shabaab certainly bears responsibility for any of its actions that prevented food from reaching people in need, other major pieces are missing from this story of man-made disaster--including climate change, agricultural policy and the history of U.S. foreign policy in Somalia.

Weather effects are compounded by poor agricultural policies. A lonely Washington Post op-ed (7/29/11) by Macalester College professor William G. Moseley pointed out that a market-based agricultural agenda, pushing cash crops and large-scale commercial farming, started under colonial rule and was ramped up by development banks. These policies, Moseley explained, left people more vulnerable to drought years than in the past, when they grew and stored food for consumption. Understanding this has important implications, he argued:

The problem is that the USAID plan for agricultural development in Africa has stressed a "New Green Revolution" involving improved seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. While this energy-intensive approach may make sense in some contexts, it is financially out of reach of the poorest of poor farmers, who are the most likely to face food shortfalls. A more realistic approach would play down imported seeds and commercial agriculture in favor of enhanced traditional approaches to producing food for families and local markets.

U.S. foreign policy was perhaps the hardest to find catching blame except in alternative media. One prominent exception, an excellent September 5 piece in Time magazine by Alex Perry--"A Famine We Made?"--stood as a rare corporate media investigation of how U.S. aid policy exacerbated the famine. Generally, however, when any fault was laid at the U.S. government's doorstep, it was simply framed as a lack of efficacy: The New York Times editorial board (8/12/11) argued that the problem with U.S. policy toward Somalia for the past decade has been "a lack of focus and internal battles."

Elsewhere in the Times (8/2/11), Somalia was simply "a lawless cauldron... dominated by chaos since 1991, when clan warlords overthrew the central government and then tore apart the country." At the very end of the long report on the famine, almost as an aside, the paper mentioned that another problem with getting famine aid to Somalis is "American government restrictions," which since 2008 have made it a crime to "provide material assistance" to Al-Shabaab. "Aid officials say the restrictions have had a chilling effect," the Times reported, "because it is nearly impossible to guarantee that the Shabaab will not skim off some of the aid delivered in their areas."

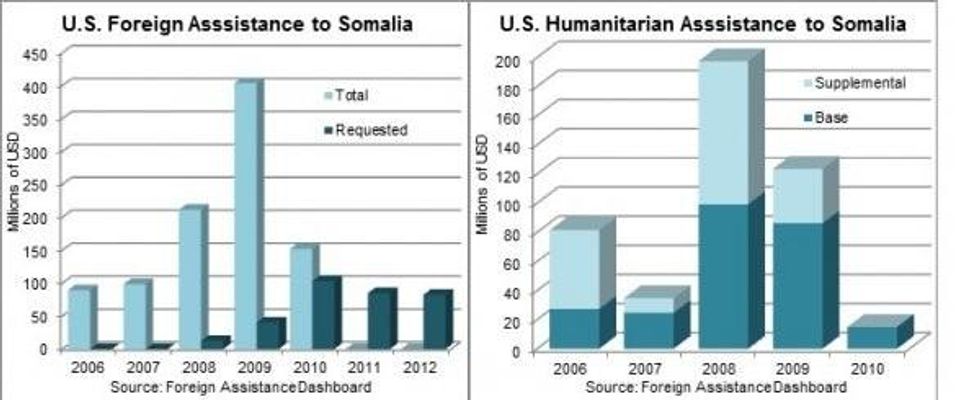

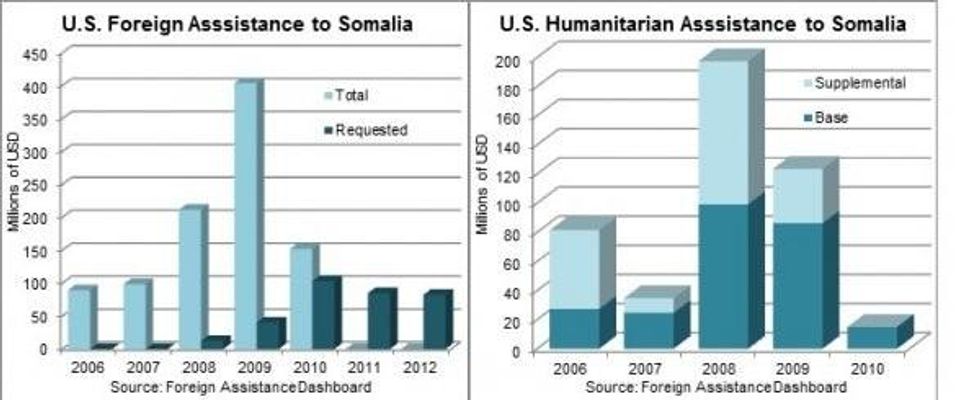

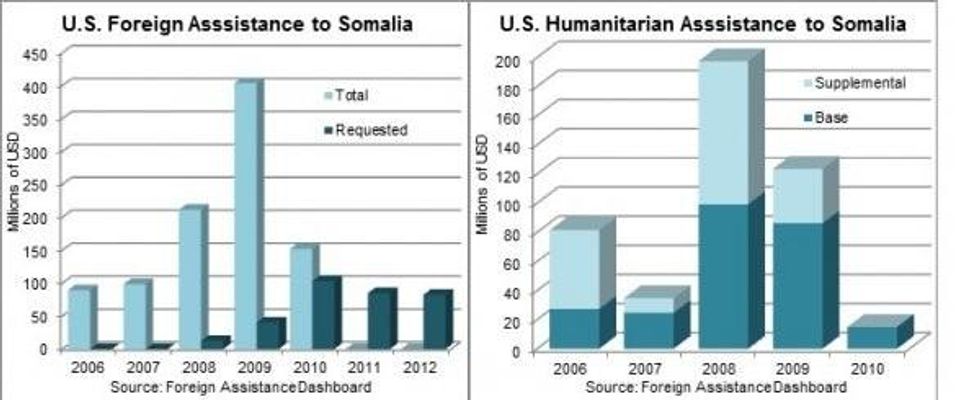

As Lauren Sutherland pointed out in a much more detailed report in the Nation (8/15/11), U.S. aid to Somalia plummeted from $237 million in 2008 to $29 million in 2010 as a result of those tightened sanctions against Al-Shabaab. Those sanctions have also "virtually prevented U.S. or U.S.-funded agencies from operating in Al-Shabaab controlled territory."

That means that even though this famine had been predicted since last August (SciDev.net, 7/14/11), U.S. counterterrorism policy kept preventative or emergency measures from being put into place until thousands had already started dying. And even once aid started flowing, the organizational infrastructure wasn't there to distribute it as quickly and effectively as it could have.

Furthermore, talk of Somalia as a "lawless cauldron...dominated by chaos since 1991" neatly erases a critical piece of recent Somali history and the U.S. role in destabilizing the country, which has led to the rise of Al-Shabaab. One of the only mentions of this U.S. role turned up by a Nexis search of U.S. newspapers and wires was an op-ed by University of Minnesota professor Abdi Ismail Samatar that appeared in a few smaller papers (e.g., Contra Costa Times, 8/20/11), courtesy of the Progressive Media Project, which works to place diverse and dissenting viewpoints on newspaper opinion pages. Wrote Samatar:

The American-supported Ethiopian invasion of Somalia in 2006 dashed Somalia's only chance in 16 years to restore a national government of its own. The invasion displaced more than 1 million people and killed 15,000 civilians. Those displaced are part of today's famine victims.

That invasion was prompted by the great reduction in Somalia's chaos by people the U.S. government didn't approve of: the Islamic Courts Union, an Islamist group that rose to power in opposition to much-hated warlords who were receiving backing from the U.S. The Islamic Courts gained control of much of the country and had brought stability with their rule, which was largely (though not uniformly) moderate. Their overthrow essentially cast the moderates out of power and drove their more radical youth wing, Al-Shabaab, into hiding to launch an insurgency that has led to the current situation (Extra!, 3-4/08).

And that Al-Qaeda connection? There's no evidence any substantial connection existed prior to the U.S.-backed overthrow of the Islamic Courts, but it served as useful propaganda to sell that invasion (Extra!, 3-4/08).

When NBC's Ann Curry (8/16/11) calls Somalia "the capital of chaos, torn to ruins by decades of war and anarchy," she forgets to note who, exactly, was partly behind that war and anarchy.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

As Somalia sank deeper into famine in late summer, with 63 percent of southern Somalia's population at risk of starvation, U.S. media coverage focused on stories of misery and resilience. Measuring children's emaciated arms and describing the scraps of dignity people struggled to maintain in refugee camps substituted for investigation of causes, or discussion of remedies beyond appeals for donations.

A typical report came from CBS Evening News (8/8/11): "The faces dusted with the desert and...the eyes that have seen too much," with an interview with a woman "who had fought to save her children in an unforgiving land." The next day (8/9/11), the network brought us "people with lessons to teach about life and death in an unforgiving land."

While drought can be a natural phenomenon, famine in the modern era is political--and avoidable. A variety of factors play into the current Somalia famine, but media could only seem to find one culprit: Islamic terrorists. Al-Shabaab, the militant youth group that controls much of Somalia and has been labeled a terrorist organization by the U.S. government, "is widely blamed for causing a famine in Somalia by forcing out many Western aid organizations," explained the New York Times (8/2/11).

And nearly all of the rest of the media agreed. "Terror Group Blocking Aid to Three Million Starving Somalis" blared a USA Today headline (8/15/11). "The spread of Islamic terrorism has turned a drought into a famine that didn't have to happen," reported NBC Nightly News' Ann Curry (8/16/11) from Mogadishu. Curry's colleague Richard Engel (NBC, 8/5/11) argued earlier: "But what may be most tragic of all, the famine here is largely man-made. Somalia is a failed state and a war zone. Peacekeepers from Uganda and Burundi are fighting to drive out Al-Qaeda backed militants called Al-Shabaab. The militants control half the country."

While Al-Shabaab certainly bears responsibility for any of its actions that prevented food from reaching people in need, other major pieces are missing from this story of man-made disaster--including climate change, agricultural policy and the history of U.S. foreign policy in Somalia.

Scientists have long warned that a warming planet would lead to more dramatic weather patterns, including droughts. And in recent years, drought has hit the Horn of Africa much more frequently than the historical average (Guardian, 8/8/11). On prominent TV news programs, though, climate change simply wasn't considered in reports on Somalia's famine. In newspapers, climate change was relegated almost exclusively to opinion pages, either in print (e.g., San Francisco Chronicle, 7/23/11; Baltimore Sun, 8/1/11) or web-only (e.g., New York Times Dot Earth Blog, 8/3/11).

While Al-Shabaab certainly bears responsibility for any of its actions that prevented food from reaching people in need, other major pieces are missing from this story of man-made disaster--including climate change, agricultural policy and the history of U.S. foreign policy in Somalia.

Weather effects are compounded by poor agricultural policies. A lonely Washington Post op-ed (7/29/11) by Macalester College professor William G. Moseley pointed out that a market-based agricultural agenda, pushing cash crops and large-scale commercial farming, started under colonial rule and was ramped up by development banks. These policies, Moseley explained, left people more vulnerable to drought years than in the past, when they grew and stored food for consumption. Understanding this has important implications, he argued:

The problem is that the USAID plan for agricultural development in Africa has stressed a "New Green Revolution" involving improved seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. While this energy-intensive approach may make sense in some contexts, it is financially out of reach of the poorest of poor farmers, who are the most likely to face food shortfalls. A more realistic approach would play down imported seeds and commercial agriculture in favor of enhanced traditional approaches to producing food for families and local markets.

U.S. foreign policy was perhaps the hardest to find catching blame except in alternative media. One prominent exception, an excellent September 5 piece in Time magazine by Alex Perry--"A Famine We Made?"--stood as a rare corporate media investigation of how U.S. aid policy exacerbated the famine. Generally, however, when any fault was laid at the U.S. government's doorstep, it was simply framed as a lack of efficacy: The New York Times editorial board (8/12/11) argued that the problem with U.S. policy toward Somalia for the past decade has been "a lack of focus and internal battles."

Elsewhere in the Times (8/2/11), Somalia was simply "a lawless cauldron... dominated by chaos since 1991, when clan warlords overthrew the central government and then tore apart the country." At the very end of the long report on the famine, almost as an aside, the paper mentioned that another problem with getting famine aid to Somalis is "American government restrictions," which since 2008 have made it a crime to "provide material assistance" to Al-Shabaab. "Aid officials say the restrictions have had a chilling effect," the Times reported, "because it is nearly impossible to guarantee that the Shabaab will not skim off some of the aid delivered in their areas."

As Lauren Sutherland pointed out in a much more detailed report in the Nation (8/15/11), U.S. aid to Somalia plummeted from $237 million in 2008 to $29 million in 2010 as a result of those tightened sanctions against Al-Shabaab. Those sanctions have also "virtually prevented U.S. or U.S.-funded agencies from operating in Al-Shabaab controlled territory."

That means that even though this famine had been predicted since last August (SciDev.net, 7/14/11), U.S. counterterrorism policy kept preventative or emergency measures from being put into place until thousands had already started dying. And even once aid started flowing, the organizational infrastructure wasn't there to distribute it as quickly and effectively as it could have.

Furthermore, talk of Somalia as a "lawless cauldron...dominated by chaos since 1991" neatly erases a critical piece of recent Somali history and the U.S. role in destabilizing the country, which has led to the rise of Al-Shabaab. One of the only mentions of this U.S. role turned up by a Nexis search of U.S. newspapers and wires was an op-ed by University of Minnesota professor Abdi Ismail Samatar that appeared in a few smaller papers (e.g., Contra Costa Times, 8/20/11), courtesy of the Progressive Media Project, which works to place diverse and dissenting viewpoints on newspaper opinion pages. Wrote Samatar:

The American-supported Ethiopian invasion of Somalia in 2006 dashed Somalia's only chance in 16 years to restore a national government of its own. The invasion displaced more than 1 million people and killed 15,000 civilians. Those displaced are part of today's famine victims.

That invasion was prompted by the great reduction in Somalia's chaos by people the U.S. government didn't approve of: the Islamic Courts Union, an Islamist group that rose to power in opposition to much-hated warlords who were receiving backing from the U.S. The Islamic Courts gained control of much of the country and had brought stability with their rule, which was largely (though not uniformly) moderate. Their overthrow essentially cast the moderates out of power and drove their more radical youth wing, Al-Shabaab, into hiding to launch an insurgency that has led to the current situation (Extra!, 3-4/08).

And that Al-Qaeda connection? There's no evidence any substantial connection existed prior to the U.S.-backed overthrow of the Islamic Courts, but it served as useful propaganda to sell that invasion (Extra!, 3-4/08).

When NBC's Ann Curry (8/16/11) calls Somalia "the capital of chaos, torn to ruins by decades of war and anarchy," she forgets to note who, exactly, was partly behind that war and anarchy.

As Somalia sank deeper into famine in late summer, with 63 percent of southern Somalia's population at risk of starvation, U.S. media coverage focused on stories of misery and resilience. Measuring children's emaciated arms and describing the scraps of dignity people struggled to maintain in refugee camps substituted for investigation of causes, or discussion of remedies beyond appeals for donations.

A typical report came from CBS Evening News (8/8/11): "The faces dusted with the desert and...the eyes that have seen too much," with an interview with a woman "who had fought to save her children in an unforgiving land." The next day (8/9/11), the network brought us "people with lessons to teach about life and death in an unforgiving land."

While drought can be a natural phenomenon, famine in the modern era is political--and avoidable. A variety of factors play into the current Somalia famine, but media could only seem to find one culprit: Islamic terrorists. Al-Shabaab, the militant youth group that controls much of Somalia and has been labeled a terrorist organization by the U.S. government, "is widely blamed for causing a famine in Somalia by forcing out many Western aid organizations," explained the New York Times (8/2/11).

And nearly all of the rest of the media agreed. "Terror Group Blocking Aid to Three Million Starving Somalis" blared a USA Today headline (8/15/11). "The spread of Islamic terrorism has turned a drought into a famine that didn't have to happen," reported NBC Nightly News' Ann Curry (8/16/11) from Mogadishu. Curry's colleague Richard Engel (NBC, 8/5/11) argued earlier: "But what may be most tragic of all, the famine here is largely man-made. Somalia is a failed state and a war zone. Peacekeepers from Uganda and Burundi are fighting to drive out Al-Qaeda backed militants called Al-Shabaab. The militants control half the country."

While Al-Shabaab certainly bears responsibility for any of its actions that prevented food from reaching people in need, other major pieces are missing from this story of man-made disaster--including climate change, agricultural policy and the history of U.S. foreign policy in Somalia.

Scientists have long warned that a warming planet would lead to more dramatic weather patterns, including droughts. And in recent years, drought has hit the Horn of Africa much more frequently than the historical average (Guardian, 8/8/11). On prominent TV news programs, though, climate change simply wasn't considered in reports on Somalia's famine. In newspapers, climate change was relegated almost exclusively to opinion pages, either in print (e.g., San Francisco Chronicle, 7/23/11; Baltimore Sun, 8/1/11) or web-only (e.g., New York Times Dot Earth Blog, 8/3/11).

While Al-Shabaab certainly bears responsibility for any of its actions that prevented food from reaching people in need, other major pieces are missing from this story of man-made disaster--including climate change, agricultural policy and the history of U.S. foreign policy in Somalia.

Weather effects are compounded by poor agricultural policies. A lonely Washington Post op-ed (7/29/11) by Macalester College professor William G. Moseley pointed out that a market-based agricultural agenda, pushing cash crops and large-scale commercial farming, started under colonial rule and was ramped up by development banks. These policies, Moseley explained, left people more vulnerable to drought years than in the past, when they grew and stored food for consumption. Understanding this has important implications, he argued:

The problem is that the USAID plan for agricultural development in Africa has stressed a "New Green Revolution" involving improved seeds, fertilizers and pesticides. While this energy-intensive approach may make sense in some contexts, it is financially out of reach of the poorest of poor farmers, who are the most likely to face food shortfalls. A more realistic approach would play down imported seeds and commercial agriculture in favor of enhanced traditional approaches to producing food for families and local markets.

U.S. foreign policy was perhaps the hardest to find catching blame except in alternative media. One prominent exception, an excellent September 5 piece in Time magazine by Alex Perry--"A Famine We Made?"--stood as a rare corporate media investigation of how U.S. aid policy exacerbated the famine. Generally, however, when any fault was laid at the U.S. government's doorstep, it was simply framed as a lack of efficacy: The New York Times editorial board (8/12/11) argued that the problem with U.S. policy toward Somalia for the past decade has been "a lack of focus and internal battles."

Elsewhere in the Times (8/2/11), Somalia was simply "a lawless cauldron... dominated by chaos since 1991, when clan warlords overthrew the central government and then tore apart the country." At the very end of the long report on the famine, almost as an aside, the paper mentioned that another problem with getting famine aid to Somalis is "American government restrictions," which since 2008 have made it a crime to "provide material assistance" to Al-Shabaab. "Aid officials say the restrictions have had a chilling effect," the Times reported, "because it is nearly impossible to guarantee that the Shabaab will not skim off some of the aid delivered in their areas."

As Lauren Sutherland pointed out in a much more detailed report in the Nation (8/15/11), U.S. aid to Somalia plummeted from $237 million in 2008 to $29 million in 2010 as a result of those tightened sanctions against Al-Shabaab. Those sanctions have also "virtually prevented U.S. or U.S.-funded agencies from operating in Al-Shabaab controlled territory."

That means that even though this famine had been predicted since last August (SciDev.net, 7/14/11), U.S. counterterrorism policy kept preventative or emergency measures from being put into place until thousands had already started dying. And even once aid started flowing, the organizational infrastructure wasn't there to distribute it as quickly and effectively as it could have.

Furthermore, talk of Somalia as a "lawless cauldron...dominated by chaos since 1991" neatly erases a critical piece of recent Somali history and the U.S. role in destabilizing the country, which has led to the rise of Al-Shabaab. One of the only mentions of this U.S. role turned up by a Nexis search of U.S. newspapers and wires was an op-ed by University of Minnesota professor Abdi Ismail Samatar that appeared in a few smaller papers (e.g., Contra Costa Times, 8/20/11), courtesy of the Progressive Media Project, which works to place diverse and dissenting viewpoints on newspaper opinion pages. Wrote Samatar:

The American-supported Ethiopian invasion of Somalia in 2006 dashed Somalia's only chance in 16 years to restore a national government of its own. The invasion displaced more than 1 million people and killed 15,000 civilians. Those displaced are part of today's famine victims.

That invasion was prompted by the great reduction in Somalia's chaos by people the U.S. government didn't approve of: the Islamic Courts Union, an Islamist group that rose to power in opposition to much-hated warlords who were receiving backing from the U.S. The Islamic Courts gained control of much of the country and had brought stability with their rule, which was largely (though not uniformly) moderate. Their overthrow essentially cast the moderates out of power and drove their more radical youth wing, Al-Shabaab, into hiding to launch an insurgency that has led to the current situation (Extra!, 3-4/08).

And that Al-Qaeda connection? There's no evidence any substantial connection existed prior to the U.S.-backed overthrow of the Islamic Courts, but it served as useful propaganda to sell that invasion (Extra!, 3-4/08).

When NBC's Ann Curry (8/16/11) calls Somalia "the capital of chaos, torn to ruins by decades of war and anarchy," she forgets to note who, exactly, was partly behind that war and anarchy.