It's not everyday that the president of the United States talks about the last fight that Dr.

Martin Luther King Jr. waged at the end of his life - a piece of history that is generally excluded from the tributes to the nation's most revered

civil rights leader.

Under fire from members of the Congressional Black Caucus and other Black leaders for not doing enough to help Black communities bearing the brunt of the Great Recession, the first African American president responded to critics last week by reflecting on the forgotten legacy of King, who spoke out against U.S.

imperialism and fought for economic justice in the last years of his life.

Speaking on the Tom Joyner radio show last Tuesday, President Obama pointed to the new memorial on the National Mall recently built in King's honor and remembered his fight for jobs and justice.

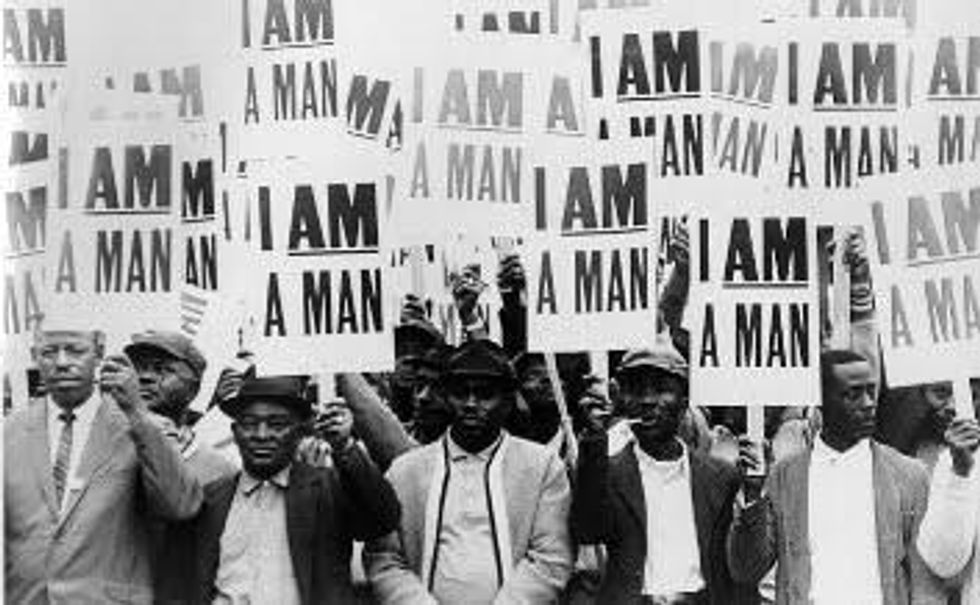

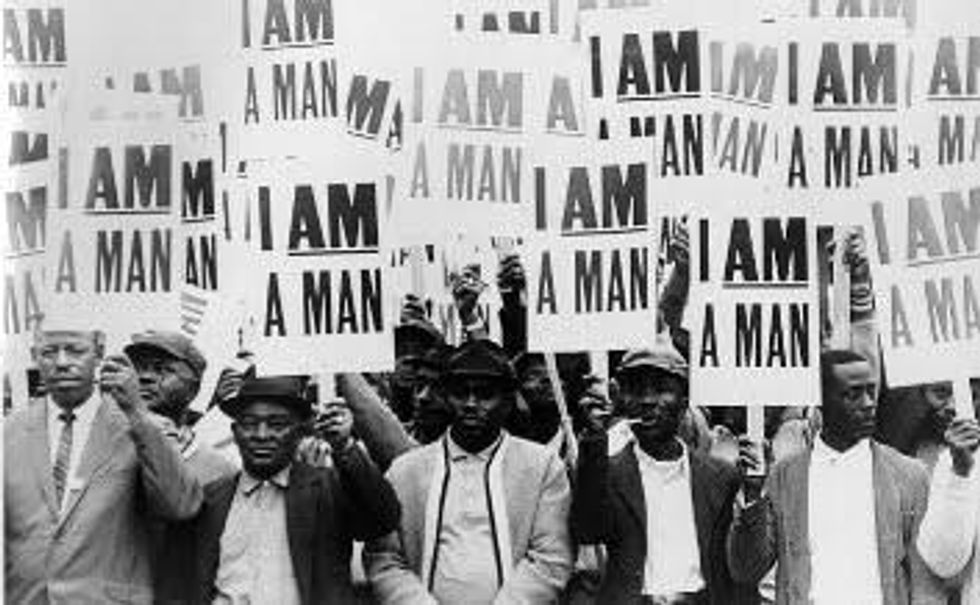

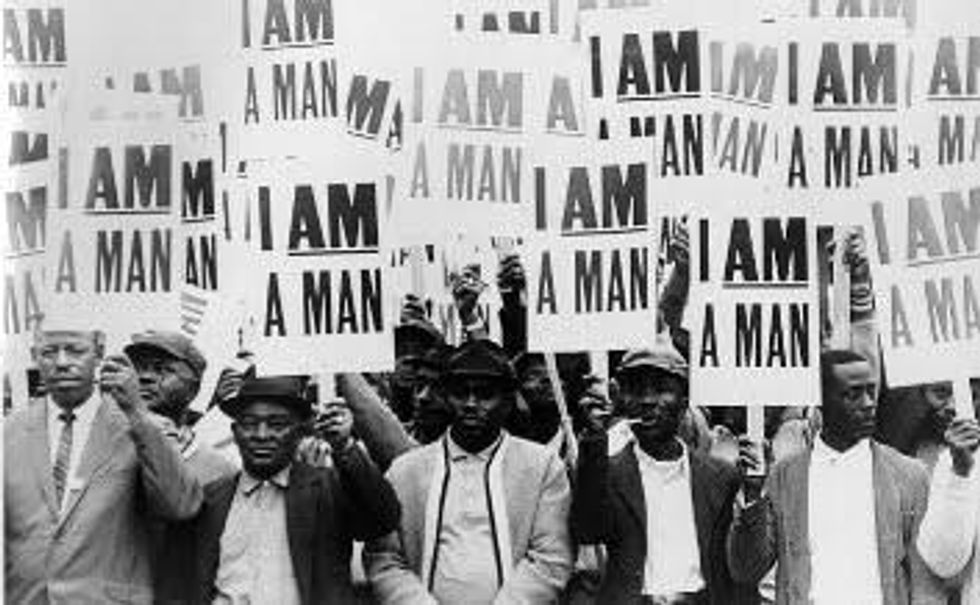

"It's always important to remember that when King gave the 'I Have a Dream' speech, that was a march for jobs and justice, not just justice," Obama said. "And the last part of his life, when he went down to Memphis, that was all about sanitation

workers saying, 'I am a man,' and then looking for economic justice and dealing with poverty."

The whitewashed image of King as a civil rights leader has been a narrative fashioned and co-opted, woven into the fabric of this country's national mythology. It omits a part of King's dream that made the civil rights icon a controversial figure toward the end of his life. While he fought against racism and Jim Crow segregation, King also condemned the United States ' militaristic foreign policy and called for a more just economic system, arguing for a radical redistribution of wealth. His last stand was a fight in Memphis alongside 1,300 striking sanitation workers - future members of AFSCME Local 1733 - just before he was assassinated.

"It's not enough for us to just remember the sanitized version of what King stood for," Obama said last week.

But there was a touch of irony in President Obama's otherwise commendable telling of King's true legacy.

It was only a few months ago that tens of thousands of union members, activists and other supporters wondered if Obama would follow King's lead - and follow through on a campaign promise - and join them on the picket line as they waged a militant two-week occupation of the state capitol in

Wisconsin in protest against Governor Scott Walker's union-busting assault on workers.

Back in November 2007 during his campaign, candidate Obama told a crowd of supporters in South Carolina that "Workers deserve to know that somebody is standing in their corner."

"If American workers are being denied their right to organize and collectively bargain when I'm in the White House, I'll put on a comfortable pair of shoes myself," he said. "I'll walk on that picket line with you as President of the United States of America ."

Yet when the time came, Obama did no such thing.

Still, the president credits martyrs like King for where he is today and argues that as a nation we need to follow through on the commitments to

social justice that King lived and died for.

For the millions of African Americans who are suffering the most from the

unemployment crisis and who hoped for more from the first Black president, Obama's homage to King's struggle for economic equality is not enough.

While overall unemployment officially stands at 9.1 percent, the unemployment rate for African Americans is 16.2 percent. And for Black youth between the ages of 16 and 24, unemployment is at 31 percent. But not only has Obama ignored calls for a targeted jobs program to address Black unemployment, the president has so far refused to fight for a national jobs program to address joblessness in general.

So how is the

Obama administration following through on King's commitment to economic justice, as illustrated in King's last struggle that the president himself highlighted?

When Dr. King arrived in Memphis in 1968, Black sanitation workers in the city had endured years of plantation-like conditions on the job. They made poverty wages and faced the racism of abusive white supervisors. After the deaths of two workers in February of 1968, the outraged all-black sanitation workforce went on strike, demanding union recognition, better wages and respect. Their slogan, "I Am a Man," was carried on placards as workers marched through the city, and it spoke to the inextricable link between racial and economic justice.

King understood this long before he got to Memphis. In 1957 he told a crowd of activists that "the forces that are anti-Negro are by and large anti-labor." He said real integration would require "complete political, economic and social equality...a whole series of measures that go beyond the specific issue of segregation."

In 1966, King began his efforts to launch what he called the

Poor People's Campaign, which he saw as the next phase of struggle. While he was unsuccessful in building such a movement, it led him to the sanitation workers in Memphis.

By March of 1968 the workers had become demoralized by a long strike that saw activists suffering police brutality and other forms of repression. King spoke to a gathering of 25,000 strikers and supporters and put the strike in the context of a new stage in the struggle:

With

Selma and the voting rights bill, one era of our struggle came to a close, and a new era came into being. Now, our struggle is for genuine equality, which means economic equality. For we know that it isn't enough to integrate lunch counters. What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn't earn enough money to buy a hamburger and cup of coffee?

King sought to escalate the sanitation workers' fight by organizing a general strike and march in the city. The work stoppage was unsuccessful and the march turned bloody. A few days later, King was assassinated, sparking riots in at least 125 cities around the country. King's fight and his murder galvanized support for the workers in Memphis . Within two weeks of his assassination, the workers won union recognition.

Notwithstanding the praise he has received from the president, it is hard to imagine that if King were alive today he would be impressed with Obama's commitment to economic justice for workers and Black workers in particular.

Not after Obama oversaw the transfer of more than a trillion dollars in public funds to

Wall Street banks. Not after he dropped the Employee Free Choice Act and left private sector workers out in the cold after so many of them knocked on doors to get him in the White House. Not after he implemented the Race to the Top program - which has fueled an all-out war on teachers - and other neoliberal education "reforms" that threaten to re-segregate schools in this country. Not after his signature health care "reform" that handed more power over to the insurance companies and included cuts to Medicare. Not after he extended the Bush tax cuts for the rich last December. Not after he turned his back on public sector unions, giving states the green light to attack public workers after he froze federal employees' pay. Not after his deficit-cutting commission proposed changes to Social Security that would slash the safety net program for the elderly. And not after he agreed to over $2.1 trillion in spending cuts over the next ten years as part of the

debt ceiling deal, adding onto previous rounds of social spending cuts that have become "the new normal" in these times of austerity.

This week, on Labor Day, Obama tried to win back the hearts of workers and organized labor in particular.

"If you want to know who helped lay these cornerstones of an American middle class you just have to look for the union label," the president said to a union crowd in Detroit on Monday. " America cannot have a strong, growing economy without a strong, growing middle class and without a strong labor movement."

But if there is a lesson to be learned based on the last two and a half years, it's that workers and their families need a labor movement that reaches communities of color and connects itself with other issues of social justice affecting poor and working-class communities nationwide. And we need a labor movement that moves and mobilizes independent of the president, no matter how flattering or sympathetic his rhetoric might be.

This is something that even candidate Obama recognized when asked in a primary debate before the 2008 election which candidate he thought King would support.

"I don't think Dr. King would endorse any of us," he said. "I think what he would call upon the American people to do is to hold us accountable. I believe change does not happen from the top down. It happens from the bottom up. Dr. King understood that."

Indeed, while the corporate bottom line reigns supreme in Washington, the bottom line is that if labor and other social movements aren't forcing the hand of President Obama, then the tea party and Wall Street will.