SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"Today, economic power has been captured by a small minority. But it has acquired this power only by accumulating the productive power of others. Their capital is simply the accumulated labor of a millions of working people, in a monetized form. It is this productive power that is the real capital, and it is this power that latently resides in every worker ..." -- Samabayaniti/The Co-operative Principles, 1928.

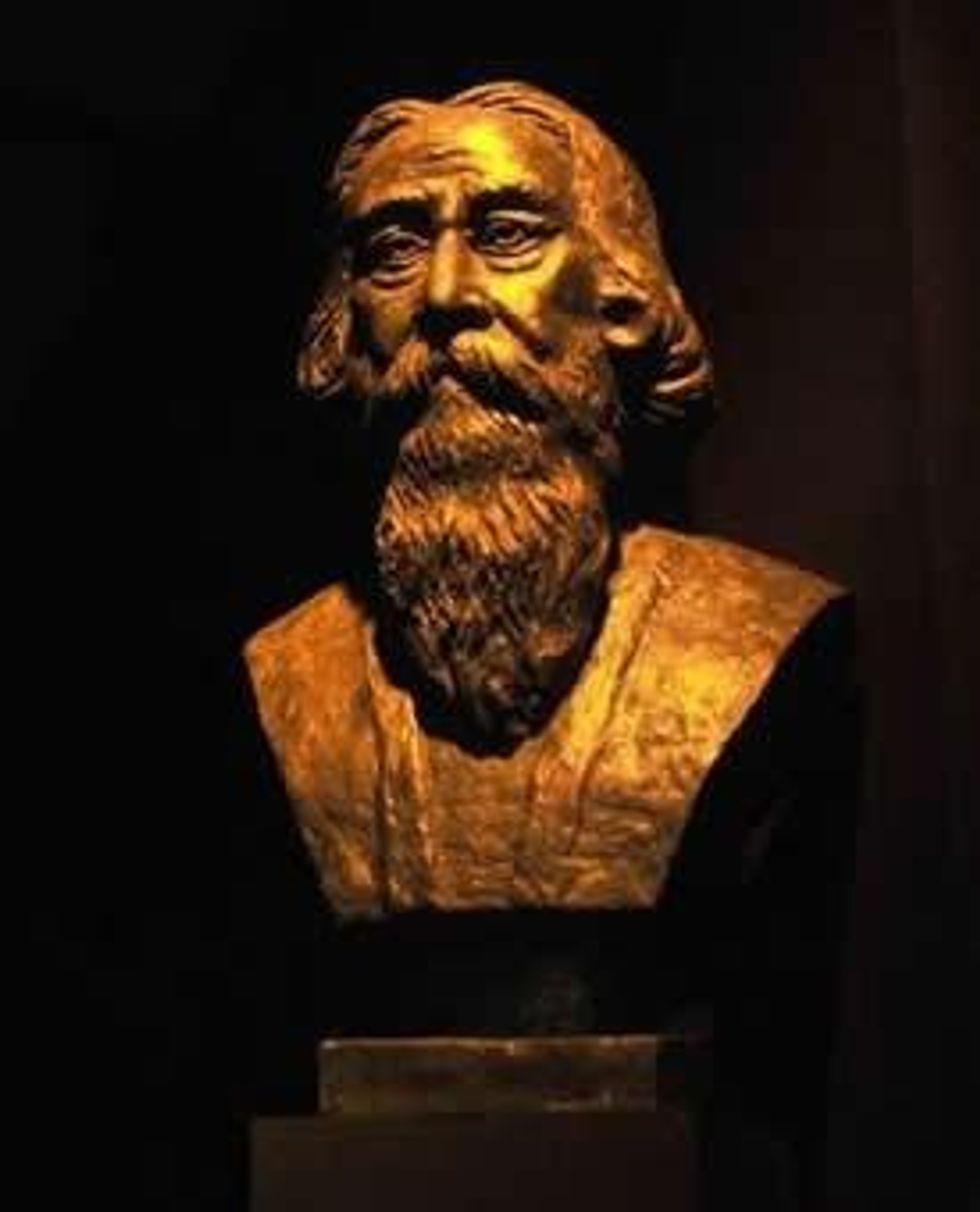

In a compelling set of essays written between 1915 and 1940, Rabindranath Tagore articulated a social vision where exploitation would give way to a just, humane, collectively owned economy. At the core of his thought was the cooperative principle. This is an idea worth revisiting on the International Day of Cooperatives, which this year falls on July 2, and even more so during the lead-up to 2012, which is the United Nations International Year of Cooperatives.

In India, the experience with the century-old cooperative movement has been mixed. There are some stunning successes: Amul, for one. There are others, too, where cooperatives have proved transformational for the marginalized. The problems are also well-known: abuse, politicization, excessive dependence on the state, and so on. But these are mere symptoms. The real disease lies elsewhere. There is little understanding, much less acceptance, of the cooperative principle and its potential. It is yet to enter the core of our social vision, leave alone public policy. Those spaces are dominated, ever more aggressively, by the competitive principle, the scepter of 'efficiency' and private gain. This is why India can emerge as one of the top wealth-generators even as 93 per cent of its working citizens toil in the informal sector. That 93 per cent contributes almost half of India's fast-growing GDP. But it has no say over the way that growth is generated -- or any voice to claim a fairer distribution of the wealth it produces. The same goes for the majority that survives on the agrarian economy.

Written some eight decades ago, Tagore's thoughts stemmed from these concerns: the growing concentration of economic power and the destruction of rural India. He wrote: "Today our villages are half-dead. If we imagine we can just/ continue to live, that would be a mistake. The dying can pull/ the living only towards death." (from The Neglected Villages, 1934).

He was deeply skeptical about the solutions proposed by the elite -- such as charity or moral enlightenment of the wealthy. These were like putting out "a raging fire by blowing at it," he wrote. Instead, he sought an ethical model of production.

What would that entail? Tagore's vision went far beyond notions like 'social responsibility' that are in vogue today. To him, ethical production required that resources (such as land and capital) are collectively owned by producers themselves. This would ensure that the produce is also collectively owned, and that all producers have a say in determining their share of value in the product of their work.

The typical small farmer, indebted and impoverished, was much in need of such a structure. "Imagine if all of our small farmers farmed their land collectively, stored their produce in a common facility and sold them through a common mechanism..." Only then can we prevent profiteering; only then can the farmer recoup the legitimate value of her labor, wrote Tagore.

Without such mechanisms, the farmer would never be able to effectively exercise the right to his land, even if he held the title. Structural conditions would make him powerless. Under these circumstances, giving the small farmer the legal right to land was no more than giving him 'the right to commit suicide.'

Indeed, in the cooperative principle, Tagore saw the possibility of challenging power, of altering power relations. Ordinary people, whose work constituted what was 'the real capital,' could only do so if they collectively owned that 'capital.' Many economists may well reject this as the misplaced idealism of an ill-informed poet. But it will resonate readily with the struggles for producer-ownership in the world today, such as Via Campesina. As the clout of agri-business grows, food inflation rises, and informal work becomes the norm, challenging dominant structures of ownership. And power is the central challenge of these movements.

In India, no amount of tinkering can make growth 'inclusive,' unless people have a say in how that growth is driven. Take the case of cotton textiles, a boom sector that has seen much growth. But has it really benefited those who have produced that growth? The cotton growers, for instance -- the largest single group within the 200,000 farmers who have taken their own lives in the past decade? Or the millions of women who work the long shifts in export factories? Even worse, the drive for profits constantly pits the growers and workers against one another. When, at the peak of the cotton crisis, cotton farmers received price support from the government, export sector workers were threatened with job losses because cotton had become 'too expensive.' (Ironically, the worst off among the cotton growers did not even benefit from price support.) As long as prices are globally determined, we are told, not much can be done to save those at the bottom. Yet, the past few months have seen global prices hit a big high -- and the government sharply restricted cotton exports to favor the textile lobby. This crippled the growers.

This brings us right back to the question of ownership. When global prices fluctuate, who decides how the gains and losses are to be shared? Certainly not the majority of workers and small farmers. But more important, global prices do not operate by magic. They reflect the same concentration of ownership and economic power. Indeed, several movements today urge consumers to use their purchasing power to counter such power. But consumer movements cannot succeed unless the productive economy is differently organized, differently owned.

Can that happen? Yes, if several conditions are in place. First, the competitive principle must be properly applied. Every institution, from schools to universities to hospitals, is increasingly being judged according to that principle, and forced to forgo its social priorities. At the same time, banks and corporations remain blatantly non-competitive, operating like cabals with little discipline or accountability. Second, among the main points of criticism of cooperatives in India has been their need for state resources. But our corporations have been also been heavily subsidized by state resources. While they flourish, cooperatives flounder. Why? Corporations enjoy state support with no interference; cooperatives do not. State support has come with levels of bureaucratic control that are incompatible with a truly autonomous, member-driven movement. Third, cooperatives cannot survive in isolated sectors. Systematic linkages between sectors and across countries are necessary if we are to harness the full political, social, economic power of the cooperative principle.

Here is a story from Peru. From its mountains comes a special brand of coffee called Cafe Femenino, produced by cooperatives of very poor indigenous women. It grew out of the women's struggle to claim their share of the value they produce. As growers of organic Fair Trade coffee they earn a premium over and above the market price. Before Cafe Femenino, the women had no access to this premium, no say in its use. Now they use it to educate their daughters who would otherwise not go to school; more than that they raise awareness against the tremendous gender violence in their communities.

There is more. In Canada, Cafe Femenino is distributed also by a workers' cooperative, creating as a result an entire coffee chain of cooperatives. Finally, as a mark of recognition of the global character of gender violence, Cafe Femenino is distributed free to shelters for abused women in Canada. The Femenino experiment has spread to six countries in Latin America and grows by the day. In India too, various experiments with women's collective enterprises have long been under way, but do not receive the attention they deserve.

As Tagore had foreseen it, the cooperative principle enables the most marginalized people to mobilize their most abundant resource: their productive power and their solidarity. 'Development projects' or paternalistic policy models for 'empowering the poor' cannot achieve this.

The choice is not between textbook theories. The lessons of everyday life have been stark, more so since 2008. The choice is between two different worlds: one driven by hyper-profit and mass distress, the other holding out the promise of shared prosperity and well-being.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

"Today, economic power has been captured by a small minority. But it has acquired this power only by accumulating the productive power of others. Their capital is simply the accumulated labor of a millions of working people, in a monetized form. It is this productive power that is the real capital, and it is this power that latently resides in every worker ..." -- Samabayaniti/The Co-operative Principles, 1928.

In a compelling set of essays written between 1915 and 1940, Rabindranath Tagore articulated a social vision where exploitation would give way to a just, humane, collectively owned economy. At the core of his thought was the cooperative principle. This is an idea worth revisiting on the International Day of Cooperatives, which this year falls on July 2, and even more so during the lead-up to 2012, which is the United Nations International Year of Cooperatives.

In India, the experience with the century-old cooperative movement has been mixed. There are some stunning successes: Amul, for one. There are others, too, where cooperatives have proved transformational for the marginalized. The problems are also well-known: abuse, politicization, excessive dependence on the state, and so on. But these are mere symptoms. The real disease lies elsewhere. There is little understanding, much less acceptance, of the cooperative principle and its potential. It is yet to enter the core of our social vision, leave alone public policy. Those spaces are dominated, ever more aggressively, by the competitive principle, the scepter of 'efficiency' and private gain. This is why India can emerge as one of the top wealth-generators even as 93 per cent of its working citizens toil in the informal sector. That 93 per cent contributes almost half of India's fast-growing GDP. But it has no say over the way that growth is generated -- or any voice to claim a fairer distribution of the wealth it produces. The same goes for the majority that survives on the agrarian economy.

Written some eight decades ago, Tagore's thoughts stemmed from these concerns: the growing concentration of economic power and the destruction of rural India. He wrote: "Today our villages are half-dead. If we imagine we can just/ continue to live, that would be a mistake. The dying can pull/ the living only towards death." (from The Neglected Villages, 1934).

He was deeply skeptical about the solutions proposed by the elite -- such as charity or moral enlightenment of the wealthy. These were like putting out "a raging fire by blowing at it," he wrote. Instead, he sought an ethical model of production.

What would that entail? Tagore's vision went far beyond notions like 'social responsibility' that are in vogue today. To him, ethical production required that resources (such as land and capital) are collectively owned by producers themselves. This would ensure that the produce is also collectively owned, and that all producers have a say in determining their share of value in the product of their work.

The typical small farmer, indebted and impoverished, was much in need of such a structure. "Imagine if all of our small farmers farmed their land collectively, stored their produce in a common facility and sold them through a common mechanism..." Only then can we prevent profiteering; only then can the farmer recoup the legitimate value of her labor, wrote Tagore.

Without such mechanisms, the farmer would never be able to effectively exercise the right to his land, even if he held the title. Structural conditions would make him powerless. Under these circumstances, giving the small farmer the legal right to land was no more than giving him 'the right to commit suicide.'

Indeed, in the cooperative principle, Tagore saw the possibility of challenging power, of altering power relations. Ordinary people, whose work constituted what was 'the real capital,' could only do so if they collectively owned that 'capital.' Many economists may well reject this as the misplaced idealism of an ill-informed poet. But it will resonate readily with the struggles for producer-ownership in the world today, such as Via Campesina. As the clout of agri-business grows, food inflation rises, and informal work becomes the norm, challenging dominant structures of ownership. And power is the central challenge of these movements.

In India, no amount of tinkering can make growth 'inclusive,' unless people have a say in how that growth is driven. Take the case of cotton textiles, a boom sector that has seen much growth. But has it really benefited those who have produced that growth? The cotton growers, for instance -- the largest single group within the 200,000 farmers who have taken their own lives in the past decade? Or the millions of women who work the long shifts in export factories? Even worse, the drive for profits constantly pits the growers and workers against one another. When, at the peak of the cotton crisis, cotton farmers received price support from the government, export sector workers were threatened with job losses because cotton had become 'too expensive.' (Ironically, the worst off among the cotton growers did not even benefit from price support.) As long as prices are globally determined, we are told, not much can be done to save those at the bottom. Yet, the past few months have seen global prices hit a big high -- and the government sharply restricted cotton exports to favor the textile lobby. This crippled the growers.

This brings us right back to the question of ownership. When global prices fluctuate, who decides how the gains and losses are to be shared? Certainly not the majority of workers and small farmers. But more important, global prices do not operate by magic. They reflect the same concentration of ownership and economic power. Indeed, several movements today urge consumers to use their purchasing power to counter such power. But consumer movements cannot succeed unless the productive economy is differently organized, differently owned.

Can that happen? Yes, if several conditions are in place. First, the competitive principle must be properly applied. Every institution, from schools to universities to hospitals, is increasingly being judged according to that principle, and forced to forgo its social priorities. At the same time, banks and corporations remain blatantly non-competitive, operating like cabals with little discipline or accountability. Second, among the main points of criticism of cooperatives in India has been their need for state resources. But our corporations have been also been heavily subsidized by state resources. While they flourish, cooperatives flounder. Why? Corporations enjoy state support with no interference; cooperatives do not. State support has come with levels of bureaucratic control that are incompatible with a truly autonomous, member-driven movement. Third, cooperatives cannot survive in isolated sectors. Systematic linkages between sectors and across countries are necessary if we are to harness the full political, social, economic power of the cooperative principle.

Here is a story from Peru. From its mountains comes a special brand of coffee called Cafe Femenino, produced by cooperatives of very poor indigenous women. It grew out of the women's struggle to claim their share of the value they produce. As growers of organic Fair Trade coffee they earn a premium over and above the market price. Before Cafe Femenino, the women had no access to this premium, no say in its use. Now they use it to educate their daughters who would otherwise not go to school; more than that they raise awareness against the tremendous gender violence in their communities.

There is more. In Canada, Cafe Femenino is distributed also by a workers' cooperative, creating as a result an entire coffee chain of cooperatives. Finally, as a mark of recognition of the global character of gender violence, Cafe Femenino is distributed free to shelters for abused women in Canada. The Femenino experiment has spread to six countries in Latin America and grows by the day. In India too, various experiments with women's collective enterprises have long been under way, but do not receive the attention they deserve.

As Tagore had foreseen it, the cooperative principle enables the most marginalized people to mobilize their most abundant resource: their productive power and their solidarity. 'Development projects' or paternalistic policy models for 'empowering the poor' cannot achieve this.

The choice is not between textbook theories. The lessons of everyday life have been stark, more so since 2008. The choice is between two different worlds: one driven by hyper-profit and mass distress, the other holding out the promise of shared prosperity and well-being.

"Today, economic power has been captured by a small minority. But it has acquired this power only by accumulating the productive power of others. Their capital is simply the accumulated labor of a millions of working people, in a monetized form. It is this productive power that is the real capital, and it is this power that latently resides in every worker ..." -- Samabayaniti/The Co-operative Principles, 1928.

In a compelling set of essays written between 1915 and 1940, Rabindranath Tagore articulated a social vision where exploitation would give way to a just, humane, collectively owned economy. At the core of his thought was the cooperative principle. This is an idea worth revisiting on the International Day of Cooperatives, which this year falls on July 2, and even more so during the lead-up to 2012, which is the United Nations International Year of Cooperatives.

In India, the experience with the century-old cooperative movement has been mixed. There are some stunning successes: Amul, for one. There are others, too, where cooperatives have proved transformational for the marginalized. The problems are also well-known: abuse, politicization, excessive dependence on the state, and so on. But these are mere symptoms. The real disease lies elsewhere. There is little understanding, much less acceptance, of the cooperative principle and its potential. It is yet to enter the core of our social vision, leave alone public policy. Those spaces are dominated, ever more aggressively, by the competitive principle, the scepter of 'efficiency' and private gain. This is why India can emerge as one of the top wealth-generators even as 93 per cent of its working citizens toil in the informal sector. That 93 per cent contributes almost half of India's fast-growing GDP. But it has no say over the way that growth is generated -- or any voice to claim a fairer distribution of the wealth it produces. The same goes for the majority that survives on the agrarian economy.

Written some eight decades ago, Tagore's thoughts stemmed from these concerns: the growing concentration of economic power and the destruction of rural India. He wrote: "Today our villages are half-dead. If we imagine we can just/ continue to live, that would be a mistake. The dying can pull/ the living only towards death." (from The Neglected Villages, 1934).

He was deeply skeptical about the solutions proposed by the elite -- such as charity or moral enlightenment of the wealthy. These were like putting out "a raging fire by blowing at it," he wrote. Instead, he sought an ethical model of production.

What would that entail? Tagore's vision went far beyond notions like 'social responsibility' that are in vogue today. To him, ethical production required that resources (such as land and capital) are collectively owned by producers themselves. This would ensure that the produce is also collectively owned, and that all producers have a say in determining their share of value in the product of their work.

The typical small farmer, indebted and impoverished, was much in need of such a structure. "Imagine if all of our small farmers farmed their land collectively, stored their produce in a common facility and sold them through a common mechanism..." Only then can we prevent profiteering; only then can the farmer recoup the legitimate value of her labor, wrote Tagore.

Without such mechanisms, the farmer would never be able to effectively exercise the right to his land, even if he held the title. Structural conditions would make him powerless. Under these circumstances, giving the small farmer the legal right to land was no more than giving him 'the right to commit suicide.'

Indeed, in the cooperative principle, Tagore saw the possibility of challenging power, of altering power relations. Ordinary people, whose work constituted what was 'the real capital,' could only do so if they collectively owned that 'capital.' Many economists may well reject this as the misplaced idealism of an ill-informed poet. But it will resonate readily with the struggles for producer-ownership in the world today, such as Via Campesina. As the clout of agri-business grows, food inflation rises, and informal work becomes the norm, challenging dominant structures of ownership. And power is the central challenge of these movements.

In India, no amount of tinkering can make growth 'inclusive,' unless people have a say in how that growth is driven. Take the case of cotton textiles, a boom sector that has seen much growth. But has it really benefited those who have produced that growth? The cotton growers, for instance -- the largest single group within the 200,000 farmers who have taken their own lives in the past decade? Or the millions of women who work the long shifts in export factories? Even worse, the drive for profits constantly pits the growers and workers against one another. When, at the peak of the cotton crisis, cotton farmers received price support from the government, export sector workers were threatened with job losses because cotton had become 'too expensive.' (Ironically, the worst off among the cotton growers did not even benefit from price support.) As long as prices are globally determined, we are told, not much can be done to save those at the bottom. Yet, the past few months have seen global prices hit a big high -- and the government sharply restricted cotton exports to favor the textile lobby. This crippled the growers.

This brings us right back to the question of ownership. When global prices fluctuate, who decides how the gains and losses are to be shared? Certainly not the majority of workers and small farmers. But more important, global prices do not operate by magic. They reflect the same concentration of ownership and economic power. Indeed, several movements today urge consumers to use their purchasing power to counter such power. But consumer movements cannot succeed unless the productive economy is differently organized, differently owned.

Can that happen? Yes, if several conditions are in place. First, the competitive principle must be properly applied. Every institution, from schools to universities to hospitals, is increasingly being judged according to that principle, and forced to forgo its social priorities. At the same time, banks and corporations remain blatantly non-competitive, operating like cabals with little discipline or accountability. Second, among the main points of criticism of cooperatives in India has been their need for state resources. But our corporations have been also been heavily subsidized by state resources. While they flourish, cooperatives flounder. Why? Corporations enjoy state support with no interference; cooperatives do not. State support has come with levels of bureaucratic control that are incompatible with a truly autonomous, member-driven movement. Third, cooperatives cannot survive in isolated sectors. Systematic linkages between sectors and across countries are necessary if we are to harness the full political, social, economic power of the cooperative principle.

Here is a story from Peru. From its mountains comes a special brand of coffee called Cafe Femenino, produced by cooperatives of very poor indigenous women. It grew out of the women's struggle to claim their share of the value they produce. As growers of organic Fair Trade coffee they earn a premium over and above the market price. Before Cafe Femenino, the women had no access to this premium, no say in its use. Now they use it to educate their daughters who would otherwise not go to school; more than that they raise awareness against the tremendous gender violence in their communities.

There is more. In Canada, Cafe Femenino is distributed also by a workers' cooperative, creating as a result an entire coffee chain of cooperatives. Finally, as a mark of recognition of the global character of gender violence, Cafe Femenino is distributed free to shelters for abused women in Canada. The Femenino experiment has spread to six countries in Latin America and grows by the day. In India too, various experiments with women's collective enterprises have long been under way, but do not receive the attention they deserve.

As Tagore had foreseen it, the cooperative principle enables the most marginalized people to mobilize their most abundant resource: their productive power and their solidarity. 'Development projects' or paternalistic policy models for 'empowering the poor' cannot achieve this.

The choice is not between textbook theories. The lessons of everyday life have been stark, more so since 2008. The choice is between two different worlds: one driven by hyper-profit and mass distress, the other holding out the promise of shared prosperity and well-being.