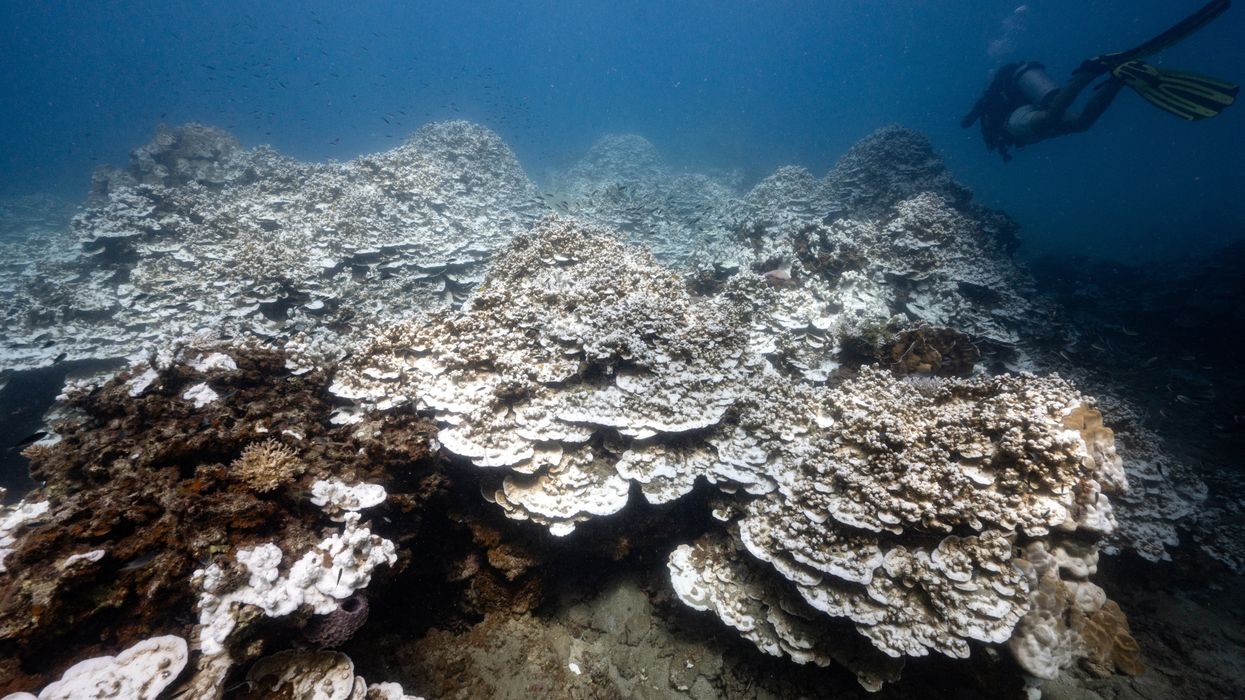

'Graveyard of Corals': Bleaching Led to Great Barrier Reef's Worst Die-Off on Record

"We will ultimately get to a tipping point where coral cover can't bounce back," warned one researcher. "We have to mitigate the root causes of the problem and reduce emissions and stabilize temperatures."

After last year's climate-fueled bleaching in Australia's famed Great Barrier Reef, large swaths of the GBR suffered the worst coral die-off since records began, a government report revealed Wednesday, prompting renewed calls for reducing greenhouse gas emissions as well as reef conservation and restoration.

The GBR "experienced unprecedented levels of heat stress, which caused the most spatially extensive and severe bleaching recorded to date," the Australian Institute of Marine Science's (AIMS) annual report states.

AIMS studied the health of 124 coral reefs between August 2024 and May 2025 and found that northern and southern branches of the approximately 1,400-mile (2,300 km) GBR suffered the "largest annual decline in coral cover" ever recorded since monitoring began nearly 40 years ago.

Data collected last year from aerial surveys showed that 75% of the GBR had been bleached amid record heat driven by the worsening climate emergency. The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration warned in March 2024 that the bleaching would likely be the worst the world had ever seen.

The new report confirmed that "the 2024 event had the largest spatial footprint ever recorded on the GBR, with high to extreme bleaching prevalence observed across all three regions" of the GBR.

According to AIMS:

In 2025, hard coral cover declined substantially across the GBR, although considerable coral cover remains in all three regions. Regional declines ranged between 14% and 30% compared to 2024 levels, with some individual reefs experiencing coral declines of up to 70.8%. These declines are primarily attributed to coral mortality from the 2024 mass coral bleaching event, compounded by the cumulative impacts of two cyclones in December 2023 and January 2024, freshwater inundation, and some crown-of-thorns starfish activity.

In 2025, 48% of surveyed reefs underwent a decline in percentage coral cover, 42% showed no net change, and only 10% had an increase. Reefs with stable or increasing coral cover were predominantly located in the central GBR.

Scientists described the resulting seascape as a "graveyard of corals."

AIMS research lead Mike Emslie told Agence France-Presse that the "number one cause" of GBR coral decline "is climate change."

"There is no doubt about that," Emslie added.

The problem is by no means limited to the GBR. A mass global bleaching event has devastated more than 80% of the world's coral reefs over the past two years, affecting 82 countries and territories.

Prior to the current die-off, the last major GBR bleaching event occurred in 2014-17, when scientists said nearly one-third of its coral died and approximately 15% of all reefs worldwide experienced major coral deaths.

"These impacts we are seeing are serious and substantial and the bleaching events are coming closer and closer together," Emslie said in a separate interview with The Guardian.

"We will ultimately get to a tipping point where coral cover can't bounce back because disturbances come so quickly that there's no time left for recovery," he warned. "We have to mitigate the root causes of the problem and reduce emissions and stabilize temperatures."

AIMS called for greater global efforts to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions fueling planetary heating, "continued good local management," and more interventions "to help corals adapt and recover."

Larissa Waters, leader of the Australian Greens and a federal senator representing Queensland, on Monday urged the governing Labor Party to "follow the science, set 2035 targets at net-zero, stop new coal and gas, or risk losing our reef, its immense biodiversity, and the 60,000 jobs it sustains."