SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

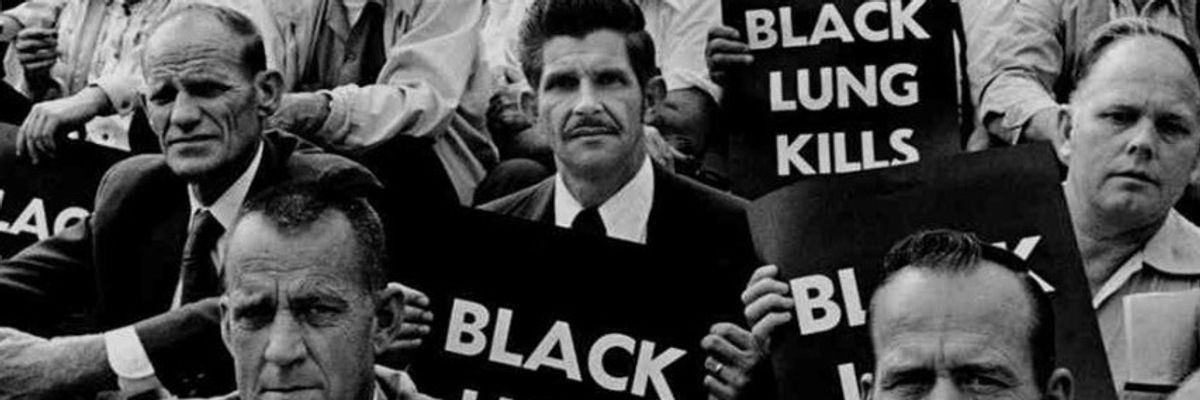

Miners protest holding signs reading, "Black lung kills."

How can we beat back the Trump administration’s assaults on working people, the environment, and democratic rights? The coal miners of 1969 offer us a strategic proposal.

If there was any doubt that U.S. President Donald Trump’s love of coal is driven by concern for coal companies’ profits rather than workers’ well-being, further proof came on April 8.

The same day he announced new measures to prop up the industry, his Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) paused a rule limiting silica dust in mines. Trump also plans to close dozens of MSHA field offices and gut the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), which both play essential roles in protecting coal workers.

Since the paused rule would save thousands of mineworkers from death and illness, the unions representing them have sued the administration.

Lawsuits may reduce the damage from Trump’s mass-homicidal orgy. But they won’t reverse five decades of unchecked, unilateral class war by U.S. elites, nor stop polluters from destroying the habitability of our Earth.

Whatever the courts decide in this case, it’s clear that lawsuits won’t be enough to stop the Trump administration. Whether its targets are workers, children, refugees, patients, the millions of ill and starving people who will be killed by sadistic cuts to foreign aid, or the entire world, defeating the assaults will require additional weapons. Coal workers’ history here is instructive.

Coal workers have won their biggest victories not through lawsuits but by striking. In the 1950s a U.S. coal miner was killed on the job every 18 hours. In later decades that rate declined significantly, and not just because of downsizing. Mine safety was strongly correlated with workers’ collective action: More frequent strikes meant fewer injuries and fatalities.

Known deaths on the job don’t include the many thousands who died prematurely from pneumoconiosis, caused by inhaling coal dust. It took the historic “black lung” strikes of 1969 to impose limits on dust and methane levels and to win compensation for disabled workers.

A few months before, 78 workers had been killed in an explosion at Consolidation Coal’s mine outside Farmington, West Virginia. The accident brought national attention to miners’ plight. Yet similar accidents had resulted in toothless reforms to safety regulations.

That might have happened again in 1969. Coal companies opposed strong regulations, and other powerholders dutifully obeyed. West Virginia’s governor wrote off the explosion as just “one of the hazards of being a miner.” President Lyndon Johnson’s assistant secretary of the interior lauded Consolidation Coal’s efforts “to make this a safe mine.” The autocratic president of the United Mineworkers called Consolidation “one of the best companies to work with as far as cooperation and safety are concerned.”

It was rank-and-file coal miners, not the top union leaders, who pushed for legislative reform. They formed the West Virginia Black Lung Association in January 1969. Aided by a handful of physicians, they organized mass meetings to educate and rally coworkers. They quickly realized that lobbying wouldn’t be enough. On February 11, thousands of miners went to Charleston to demand a robust compensation law. Some carried signs threatening to strike: “No law, no work.”

When coal companies obstructed the bill’s passage, rank-and-file workers responded with a wave of strikes unsanctioned by the union leadership. Within two weeks some 30,000 were on strike, rising to 45,000 by early March. They “shut down virtually all coal mining operations in the state,” observed the Charleston Gazette. Some miners in Ohio and Pennsylvania struck in solidarity.

The legislature and governor got the message. The strike worked, and even strengthened the final legislation by requiring companies to pay compensation unless they could prove a worker’s lung illness was not caused by coal dust. The Gazette’s editors accused the workers of “lobbying with [a] club,” decrying that state legislators had “felt compelled to” vote for a strong compensation law. The worst fear of companies and politicians alike was that more workers would begin using strikes to influence government, not just their bosses.

The impact rippled outward from West Virginia. Several other coal-producing states soon passed similar laws. In December the U.S. Congress passed the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act. The federal bill extended compensation for black lung victims across the country. It also mandated the world’s toughest coal dust standard.

President Richard Nixon initially refused to sign it. After a week and half of White House stalling, around 1,200 West Virginia mineworkers launched another wildcat strike. The coal barons warned that “a widespread work stoppage now could pose a serious threat to fuel supplies,” reported The New York Times. Nixon quickly changed his mind. He signed the bill within “a matter of hours.”

The law brought compensation for around half a million disabled mineworkers over the next decade. It also made a real contribution to workplace safety. Unfortunately black lung has since come roaring back in the neoliberal era, a sign of government’s unwillingness to hold coal companies accountable.

Beyond their direct impacts, the black lung strikes hold a lesson for today’s resistance. How can we beat back the Trump administration’s assaults on working people, the environment, and democratic rights? The coal miners of 1969 offer us a strategic proposal.

Lawsuits may reduce the damage from Trump’s mass-homicidal orgy. But they won’t reverse five decades of unchecked, unilateral class war by U.S. elites, nor stop polluters from destroying the habitability of our Earth.

We need more aggressive measures. As the heroes of the black lung strikes realized, those measures only become feasible if we embrace the daily work of organizing and educating the people around us.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

If there was any doubt that U.S. President Donald Trump’s love of coal is driven by concern for coal companies’ profits rather than workers’ well-being, further proof came on April 8.

The same day he announced new measures to prop up the industry, his Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) paused a rule limiting silica dust in mines. Trump also plans to close dozens of MSHA field offices and gut the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), which both play essential roles in protecting coal workers.

Since the paused rule would save thousands of mineworkers from death and illness, the unions representing them have sued the administration.

Lawsuits may reduce the damage from Trump’s mass-homicidal orgy. But they won’t reverse five decades of unchecked, unilateral class war by U.S. elites, nor stop polluters from destroying the habitability of our Earth.

Whatever the courts decide in this case, it’s clear that lawsuits won’t be enough to stop the Trump administration. Whether its targets are workers, children, refugees, patients, the millions of ill and starving people who will be killed by sadistic cuts to foreign aid, or the entire world, defeating the assaults will require additional weapons. Coal workers’ history here is instructive.

Coal workers have won their biggest victories not through lawsuits but by striking. In the 1950s a U.S. coal miner was killed on the job every 18 hours. In later decades that rate declined significantly, and not just because of downsizing. Mine safety was strongly correlated with workers’ collective action: More frequent strikes meant fewer injuries and fatalities.

Known deaths on the job don’t include the many thousands who died prematurely from pneumoconiosis, caused by inhaling coal dust. It took the historic “black lung” strikes of 1969 to impose limits on dust and methane levels and to win compensation for disabled workers.

A few months before, 78 workers had been killed in an explosion at Consolidation Coal’s mine outside Farmington, West Virginia. The accident brought national attention to miners’ plight. Yet similar accidents had resulted in toothless reforms to safety regulations.

That might have happened again in 1969. Coal companies opposed strong regulations, and other powerholders dutifully obeyed. West Virginia’s governor wrote off the explosion as just “one of the hazards of being a miner.” President Lyndon Johnson’s assistant secretary of the interior lauded Consolidation Coal’s efforts “to make this a safe mine.” The autocratic president of the United Mineworkers called Consolidation “one of the best companies to work with as far as cooperation and safety are concerned.”

It was rank-and-file coal miners, not the top union leaders, who pushed for legislative reform. They formed the West Virginia Black Lung Association in January 1969. Aided by a handful of physicians, they organized mass meetings to educate and rally coworkers. They quickly realized that lobbying wouldn’t be enough. On February 11, thousands of miners went to Charleston to demand a robust compensation law. Some carried signs threatening to strike: “No law, no work.”

When coal companies obstructed the bill’s passage, rank-and-file workers responded with a wave of strikes unsanctioned by the union leadership. Within two weeks some 30,000 were on strike, rising to 45,000 by early March. They “shut down virtually all coal mining operations in the state,” observed the Charleston Gazette. Some miners in Ohio and Pennsylvania struck in solidarity.

The legislature and governor got the message. The strike worked, and even strengthened the final legislation by requiring companies to pay compensation unless they could prove a worker’s lung illness was not caused by coal dust. The Gazette’s editors accused the workers of “lobbying with [a] club,” decrying that state legislators had “felt compelled to” vote for a strong compensation law. The worst fear of companies and politicians alike was that more workers would begin using strikes to influence government, not just their bosses.

The impact rippled outward from West Virginia. Several other coal-producing states soon passed similar laws. In December the U.S. Congress passed the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act. The federal bill extended compensation for black lung victims across the country. It also mandated the world’s toughest coal dust standard.

President Richard Nixon initially refused to sign it. After a week and half of White House stalling, around 1,200 West Virginia mineworkers launched another wildcat strike. The coal barons warned that “a widespread work stoppage now could pose a serious threat to fuel supplies,” reported The New York Times. Nixon quickly changed his mind. He signed the bill within “a matter of hours.”

The law brought compensation for around half a million disabled mineworkers over the next decade. It also made a real contribution to workplace safety. Unfortunately black lung has since come roaring back in the neoliberal era, a sign of government’s unwillingness to hold coal companies accountable.

Beyond their direct impacts, the black lung strikes hold a lesson for today’s resistance. How can we beat back the Trump administration’s assaults on working people, the environment, and democratic rights? The coal miners of 1969 offer us a strategic proposal.

Lawsuits may reduce the damage from Trump’s mass-homicidal orgy. But they won’t reverse five decades of unchecked, unilateral class war by U.S. elites, nor stop polluters from destroying the habitability of our Earth.

We need more aggressive measures. As the heroes of the black lung strikes realized, those measures only become feasible if we embrace the daily work of organizing and educating the people around us.

If there was any doubt that U.S. President Donald Trump’s love of coal is driven by concern for coal companies’ profits rather than workers’ well-being, further proof came on April 8.

The same day he announced new measures to prop up the industry, his Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) paused a rule limiting silica dust in mines. Trump also plans to close dozens of MSHA field offices and gut the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), which both play essential roles in protecting coal workers.

Since the paused rule would save thousands of mineworkers from death and illness, the unions representing them have sued the administration.

Lawsuits may reduce the damage from Trump’s mass-homicidal orgy. But they won’t reverse five decades of unchecked, unilateral class war by U.S. elites, nor stop polluters from destroying the habitability of our Earth.

Whatever the courts decide in this case, it’s clear that lawsuits won’t be enough to stop the Trump administration. Whether its targets are workers, children, refugees, patients, the millions of ill and starving people who will be killed by sadistic cuts to foreign aid, or the entire world, defeating the assaults will require additional weapons. Coal workers’ history here is instructive.

Coal workers have won their biggest victories not through lawsuits but by striking. In the 1950s a U.S. coal miner was killed on the job every 18 hours. In later decades that rate declined significantly, and not just because of downsizing. Mine safety was strongly correlated with workers’ collective action: More frequent strikes meant fewer injuries and fatalities.

Known deaths on the job don’t include the many thousands who died prematurely from pneumoconiosis, caused by inhaling coal dust. It took the historic “black lung” strikes of 1969 to impose limits on dust and methane levels and to win compensation for disabled workers.

A few months before, 78 workers had been killed in an explosion at Consolidation Coal’s mine outside Farmington, West Virginia. The accident brought national attention to miners’ plight. Yet similar accidents had resulted in toothless reforms to safety regulations.

That might have happened again in 1969. Coal companies opposed strong regulations, and other powerholders dutifully obeyed. West Virginia’s governor wrote off the explosion as just “one of the hazards of being a miner.” President Lyndon Johnson’s assistant secretary of the interior lauded Consolidation Coal’s efforts “to make this a safe mine.” The autocratic president of the United Mineworkers called Consolidation “one of the best companies to work with as far as cooperation and safety are concerned.”

It was rank-and-file coal miners, not the top union leaders, who pushed for legislative reform. They formed the West Virginia Black Lung Association in January 1969. Aided by a handful of physicians, they organized mass meetings to educate and rally coworkers. They quickly realized that lobbying wouldn’t be enough. On February 11, thousands of miners went to Charleston to demand a robust compensation law. Some carried signs threatening to strike: “No law, no work.”

When coal companies obstructed the bill’s passage, rank-and-file workers responded with a wave of strikes unsanctioned by the union leadership. Within two weeks some 30,000 were on strike, rising to 45,000 by early March. They “shut down virtually all coal mining operations in the state,” observed the Charleston Gazette. Some miners in Ohio and Pennsylvania struck in solidarity.

The legislature and governor got the message. The strike worked, and even strengthened the final legislation by requiring companies to pay compensation unless they could prove a worker’s lung illness was not caused by coal dust. The Gazette’s editors accused the workers of “lobbying with [a] club,” decrying that state legislators had “felt compelled to” vote for a strong compensation law. The worst fear of companies and politicians alike was that more workers would begin using strikes to influence government, not just their bosses.

The impact rippled outward from West Virginia. Several other coal-producing states soon passed similar laws. In December the U.S. Congress passed the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act. The federal bill extended compensation for black lung victims across the country. It also mandated the world’s toughest coal dust standard.

President Richard Nixon initially refused to sign it. After a week and half of White House stalling, around 1,200 West Virginia mineworkers launched another wildcat strike. The coal barons warned that “a widespread work stoppage now could pose a serious threat to fuel supplies,” reported The New York Times. Nixon quickly changed his mind. He signed the bill within “a matter of hours.”

The law brought compensation for around half a million disabled mineworkers over the next decade. It also made a real contribution to workplace safety. Unfortunately black lung has since come roaring back in the neoliberal era, a sign of government’s unwillingness to hold coal companies accountable.

Beyond their direct impacts, the black lung strikes hold a lesson for today’s resistance. How can we beat back the Trump administration’s assaults on working people, the environment, and democratic rights? The coal miners of 1969 offer us a strategic proposal.

Lawsuits may reduce the damage from Trump’s mass-homicidal orgy. But they won’t reverse five decades of unchecked, unilateral class war by U.S. elites, nor stop polluters from destroying the habitability of our Earth.

We need more aggressive measures. As the heroes of the black lung strikes realized, those measures only become feasible if we embrace the daily work of organizing and educating the people around us.