SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

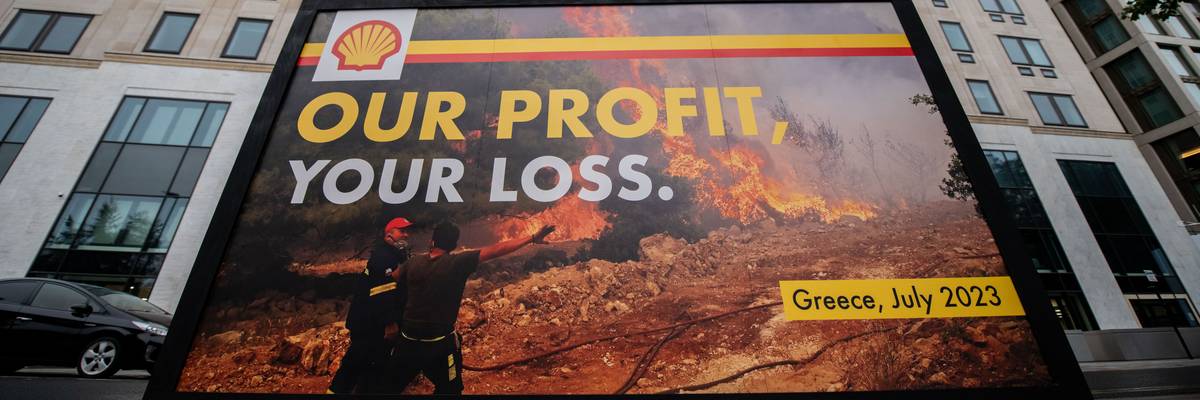

Greenpeace activists display a billboard during a protest outside Shell headquarters on July 27, 2023 in London.

Even in states with financial officers that purport to care about sustainability, way too many pensions are failing to push the companies they invest in to align with global climate goals.

Public pensions in the United States are responsible for investing and stewarding nearly $8 trillion on behalf of the American people. That is, by any measure, a lot of money. To give that figure some context, consider that $8 trillion is more than three times the annual GDP of the United Kingdom. What this means is that the people entrusted to manage our public pensions have significant power to shape and direct our economy and our world.

One way pension managers wield that power is simply through what they choose to invest in. Indeed, to track how we’re doing in the climate fight, you just need to follow the money. The International Energy Agency estimates that to be on track for the goals of the Paris Agreement we should have already stopped investing in new oil and gas development and that, by 2030, we should be investing $4.5 trillion annually in renewable energy.

That helps to explain why, for the last decade, whenever climate activists have thought about pension funds it has been to campaign for fossil fuel divestment. Divestment is an important step in the right direction and one that some major pensions, including the massive New York State and City pension funds, have already taken. More pensions should follow New York’s lead and divest from fossil fuels.

If pension managers have a single job it is protecting workers’ savings from unnecessary financial risk...

But there’s another critical way that pensions need to address the climate crisis, too: through how they use their massive investments to influence all of the other companies they invest in. To address the climate crisis, we need virtually every major company to do its bit―banks need to fund renewable energy; tech companies need to buy clean energy; steel, cement, and utility companies need to eradicate climate-warming emissions from their operations.

And public pensions, with their $8 trillion sloshing around the economy, will play a big role in deciding whether or not many of these companies will address the climate crisis with the urgency required to avoid even worse climate impacts than the catastrophic ones we’re already experiencing.

Between April and June each year, almost every major publicly-held company in the country hosts an annual shareholder meeting. At these meetings, shareholders introduce and vote on proposals that help to direct the future of the company. In recent years, shareholders of many of the country’s largest companies have been asked to consider resolutions on climate lobbying, reducing emissions, setting climate targets, and breaking ties with fossil fuel companies.

Until recently though, very few have paid attention to the voting records of major pensions. But a new report, released today by the Sierra Club, Stand.earth and Stop the Money Pipeline, takes a detailed look at the voting records of some of the largest pensions in the country.

The Hidden Risk in State Pensions report (which I helped to write) analyzes the approaches to shareholder voting and the voting records of 24 major public pensions. We only analyzed pensions in states where a state financial officer, such as the state treasurer, comptroller, or auditor, is a member of For the Long Term, a network dedicated to advocating for “more sustainable, just, and inclusive firms and markets.”

Unfortunately, our conclusions are clear: even in states with financial officers that purport to care about sustainability, way too many pensions are failing to push the companies they invest in to align with global climate goals. This is true even in several states that you might expect to care more about preventing global heating.

In our report, the $200 billion Washington state pension fund received an F grade for its proxy voting guidelines and a D- grade for its voting record. In 2023, the people responsible for investing Washington’s teachers’, firefighters’ and other public workers’ money voted against shareholder resolutions calling for companies to produce climate transition plans, set tougher climate targets, and address fossil fuel financing.

The $56 billion Colorado pension was just as bad: it voted against nearly every resolution we analyzed, and received an F for its proxy voting guidelines. Pension systems based in Maine, Nevada, and New Mexico were also among those that received Fs for their voting records.

Public pensions, with their $8 trillion sloshing around the economy, will play a big role in deciding whether or not [major] companies will address the climate crisis with the urgency required.

It’s hard to understand the rationale of pension managers in making these votes. The Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency recently released a report that concluded, “The financial impacts that result from the economic effects of climate change and the transition to a lower carbon economy pose an emerging risk to the safety and soundness of financial institutions and the financial stability of the United States.”

If pension managers have a single job it is protecting workers’ savings from unnecessary financial risk, and one of the most prudent things that pension managers can do to protect against the growing and emerging threat of climate-related financial risk is to support climate action at the companies they invest in.

But right now, that’s not happening. And the planet and the hard-earned savings of American workers are being put at risk as a result.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Public pensions in the United States are responsible for investing and stewarding nearly $8 trillion on behalf of the American people. That is, by any measure, a lot of money. To give that figure some context, consider that $8 trillion is more than three times the annual GDP of the United Kingdom. What this means is that the people entrusted to manage our public pensions have significant power to shape and direct our economy and our world.

One way pension managers wield that power is simply through what they choose to invest in. Indeed, to track how we’re doing in the climate fight, you just need to follow the money. The International Energy Agency estimates that to be on track for the goals of the Paris Agreement we should have already stopped investing in new oil and gas development and that, by 2030, we should be investing $4.5 trillion annually in renewable energy.

That helps to explain why, for the last decade, whenever climate activists have thought about pension funds it has been to campaign for fossil fuel divestment. Divestment is an important step in the right direction and one that some major pensions, including the massive New York State and City pension funds, have already taken. More pensions should follow New York’s lead and divest from fossil fuels.

If pension managers have a single job it is protecting workers’ savings from unnecessary financial risk...

But there’s another critical way that pensions need to address the climate crisis, too: through how they use their massive investments to influence all of the other companies they invest in. To address the climate crisis, we need virtually every major company to do its bit―banks need to fund renewable energy; tech companies need to buy clean energy; steel, cement, and utility companies need to eradicate climate-warming emissions from their operations.

And public pensions, with their $8 trillion sloshing around the economy, will play a big role in deciding whether or not many of these companies will address the climate crisis with the urgency required to avoid even worse climate impacts than the catastrophic ones we’re already experiencing.

Between April and June each year, almost every major publicly-held company in the country hosts an annual shareholder meeting. At these meetings, shareholders introduce and vote on proposals that help to direct the future of the company. In recent years, shareholders of many of the country’s largest companies have been asked to consider resolutions on climate lobbying, reducing emissions, setting climate targets, and breaking ties with fossil fuel companies.

Until recently though, very few have paid attention to the voting records of major pensions. But a new report, released today by the Sierra Club, Stand.earth and Stop the Money Pipeline, takes a detailed look at the voting records of some of the largest pensions in the country.

The Hidden Risk in State Pensions report (which I helped to write) analyzes the approaches to shareholder voting and the voting records of 24 major public pensions. We only analyzed pensions in states where a state financial officer, such as the state treasurer, comptroller, or auditor, is a member of For the Long Term, a network dedicated to advocating for “more sustainable, just, and inclusive firms and markets.”

Unfortunately, our conclusions are clear: even in states with financial officers that purport to care about sustainability, way too many pensions are failing to push the companies they invest in to align with global climate goals. This is true even in several states that you might expect to care more about preventing global heating.

In our report, the $200 billion Washington state pension fund received an F grade for its proxy voting guidelines and a D- grade for its voting record. In 2023, the people responsible for investing Washington’s teachers’, firefighters’ and other public workers’ money voted against shareholder resolutions calling for companies to produce climate transition plans, set tougher climate targets, and address fossil fuel financing.

The $56 billion Colorado pension was just as bad: it voted against nearly every resolution we analyzed, and received an F for its proxy voting guidelines. Pension systems based in Maine, Nevada, and New Mexico were also among those that received Fs for their voting records.

Public pensions, with their $8 trillion sloshing around the economy, will play a big role in deciding whether or not [major] companies will address the climate crisis with the urgency required.

It’s hard to understand the rationale of pension managers in making these votes. The Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency recently released a report that concluded, “The financial impacts that result from the economic effects of climate change and the transition to a lower carbon economy pose an emerging risk to the safety and soundness of financial institutions and the financial stability of the United States.”

If pension managers have a single job it is protecting workers’ savings from unnecessary financial risk, and one of the most prudent things that pension managers can do to protect against the growing and emerging threat of climate-related financial risk is to support climate action at the companies they invest in.

But right now, that’s not happening. And the planet and the hard-earned savings of American workers are being put at risk as a result.

Public pensions in the United States are responsible for investing and stewarding nearly $8 trillion on behalf of the American people. That is, by any measure, a lot of money. To give that figure some context, consider that $8 trillion is more than three times the annual GDP of the United Kingdom. What this means is that the people entrusted to manage our public pensions have significant power to shape and direct our economy and our world.

One way pension managers wield that power is simply through what they choose to invest in. Indeed, to track how we’re doing in the climate fight, you just need to follow the money. The International Energy Agency estimates that to be on track for the goals of the Paris Agreement we should have already stopped investing in new oil and gas development and that, by 2030, we should be investing $4.5 trillion annually in renewable energy.

That helps to explain why, for the last decade, whenever climate activists have thought about pension funds it has been to campaign for fossil fuel divestment. Divestment is an important step in the right direction and one that some major pensions, including the massive New York State and City pension funds, have already taken. More pensions should follow New York’s lead and divest from fossil fuels.

If pension managers have a single job it is protecting workers’ savings from unnecessary financial risk...

But there’s another critical way that pensions need to address the climate crisis, too: through how they use their massive investments to influence all of the other companies they invest in. To address the climate crisis, we need virtually every major company to do its bit―banks need to fund renewable energy; tech companies need to buy clean energy; steel, cement, and utility companies need to eradicate climate-warming emissions from their operations.

And public pensions, with their $8 trillion sloshing around the economy, will play a big role in deciding whether or not many of these companies will address the climate crisis with the urgency required to avoid even worse climate impacts than the catastrophic ones we’re already experiencing.

Between April and June each year, almost every major publicly-held company in the country hosts an annual shareholder meeting. At these meetings, shareholders introduce and vote on proposals that help to direct the future of the company. In recent years, shareholders of many of the country’s largest companies have been asked to consider resolutions on climate lobbying, reducing emissions, setting climate targets, and breaking ties with fossil fuel companies.

Until recently though, very few have paid attention to the voting records of major pensions. But a new report, released today by the Sierra Club, Stand.earth and Stop the Money Pipeline, takes a detailed look at the voting records of some of the largest pensions in the country.

The Hidden Risk in State Pensions report (which I helped to write) analyzes the approaches to shareholder voting and the voting records of 24 major public pensions. We only analyzed pensions in states where a state financial officer, such as the state treasurer, comptroller, or auditor, is a member of For the Long Term, a network dedicated to advocating for “more sustainable, just, and inclusive firms and markets.”

Unfortunately, our conclusions are clear: even in states with financial officers that purport to care about sustainability, way too many pensions are failing to push the companies they invest in to align with global climate goals. This is true even in several states that you might expect to care more about preventing global heating.

In our report, the $200 billion Washington state pension fund received an F grade for its proxy voting guidelines and a D- grade for its voting record. In 2023, the people responsible for investing Washington’s teachers’, firefighters’ and other public workers’ money voted against shareholder resolutions calling for companies to produce climate transition plans, set tougher climate targets, and address fossil fuel financing.

The $56 billion Colorado pension was just as bad: it voted against nearly every resolution we analyzed, and received an F for its proxy voting guidelines. Pension systems based in Maine, Nevada, and New Mexico were also among those that received Fs for their voting records.

Public pensions, with their $8 trillion sloshing around the economy, will play a big role in deciding whether or not [major] companies will address the climate crisis with the urgency required.

It’s hard to understand the rationale of pension managers in making these votes. The Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency recently released a report that concluded, “The financial impacts that result from the economic effects of climate change and the transition to a lower carbon economy pose an emerging risk to the safety and soundness of financial institutions and the financial stability of the United States.”

If pension managers have a single job it is protecting workers’ savings from unnecessary financial risk, and one of the most prudent things that pension managers can do to protect against the growing and emerging threat of climate-related financial risk is to support climate action at the companies they invest in.

But right now, that’s not happening. And the planet and the hard-earned savings of American workers are being put at risk as a result.