As European Union policymakers on Wednesday lauded the approval of the Artificial Intelligence Act, critics warn the legislation represents a giveaway to corporate interests and falls short in key areas.

Daniel Leufer, a senior policy analyst at the Brussels office of advocacy group Access Now, called the bloc's landmark AI legislation "a failure from a human rights perspective and a victory for industry and police."

Following negotiations to finalize the AI Act in December, the world's first sweeping regulations for the rapidly evolving technology were adopted by members of the European Parliament 523-46 with 49 abstentions. After some final formalities, the law is expected to take effect in May or June, with various provisions entering into force over the next few years.

"Even though adopting the world's first rules on the development and deployment of AI technologies is a milestone, it is disappointing that the E.U. and its 27 member states chose to prioritize the interest of industry and law enforcement agencies over protecting people and their human rights," said Mher Hakobyan, Amnesty International's advocacy adviser on artificial intelligence.

The law applies a "risk-based approach" to AI products and services. As The Associated Press reported Wednesday:

The vast majority of AI systems are expected to be low risk, such as content recommendation systems or spam filters. Companies can choose to follow voluntary requirements and codes of conduct.

High-risk uses of AI, such as in medical devices or critical infrastructure like water or electrical networks, face tougher requirements like using high-quality data and providing clear information to users.

Some AI uses are banned because they're deemed to pose an unacceptable risk, like social scoring systems that govern how people behave, some types of predictive policing, and emotion recognition systems in school and workplaces.

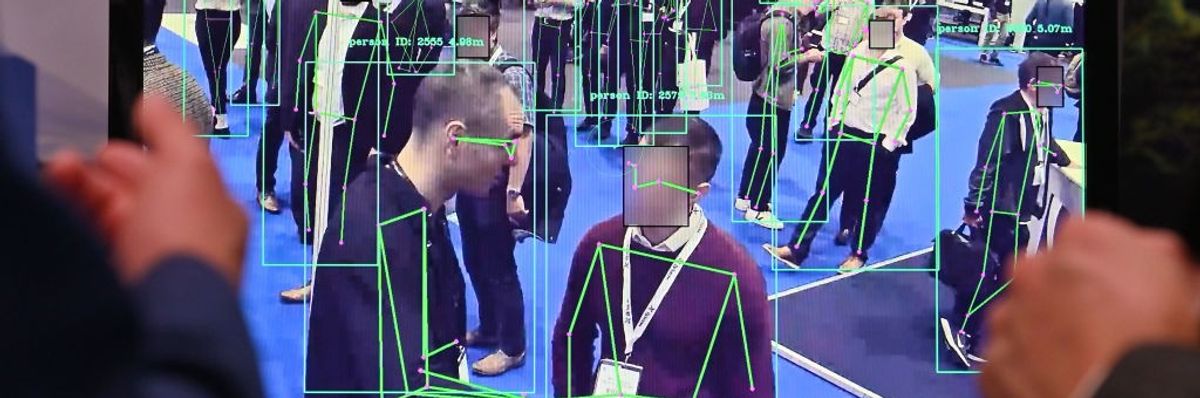

Other banned uses include police scanning faces in public using AI-powered remote "biometric identification" systems, except for serious crimes like kidnapping or terrorism.

While some praised positive commonsense guidelines and protections, Leufer said that "the new AI Act is littered with concessions to industry lobbying, exemptions for the most dangerous uses of AI by law enforcement and migration authorities, and prohibitions so full of loopholes that they don't actually ban some of the most dangerous uses of AI."

Along with also expressing concerns about how the law will impact migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers, Hakobyan highlighted that "it does not ban the reckless use and export of draconian AI technologies."

Access Now and Amnesty are part of the #ProtectNotSurveil coalition, which released a joint statement warning that the AI Act "sets a dangerous precedent," particularly with its exemptions for law enforcement, migration officials, and national security.

Other members of the coalition include EuroMed Rights, European Digital Rights, and Statewatch, whose executive director, Chris Jones, said in a statement that "the AI Act might be a new law but it fits into a much older story in which E.U. governments and agencies—including Frontex—have violated the rights of migrants and refugees for decades."

Frontex—officially the European Border and Coast Guard Agency—has long faced criticism from human rights groups for failing to protect people entering the bloc, particularly those traveling by sea.

"Implemented along with a swathe of new restrictive asylum and migration laws, the AI Act will lead to the use of digital technologies in new and harmful ways to shore up 'Fortress Europe' and to limit the arrival of vulnerable people seeking safety," Jones warned. "Civil society coalitions across and beyond Europe should work together to mitigate the worst effects of these laws, and continue to towards building societies that prioritize care over surveillance and criminalization."

"It has severe shortcomings from the point of view of fundamental rights and should not be treated as a golden standard for rights-based AI regulation."

Campaigners hope policymakers worldwide now take lessons from this legislative process.

In a Wednesday op-ed, Laura Lazaro Cabrera, counsel and director of Center for Democracy & Technology Europe's Equity and Data Program, argued the law "will become the benchmark for AI regulation globally in what has become a race against the clock as lawmakers grapple with a fast-moving development of a technology with far-reaching impacts on our basic human rights."

After the vote, Lazaro Cabrera stressed that "there's so much at stake in the implementation of the AI Act and so, as the dust settles, we all face the difficult task of unpacking a complex, lengthy, and unprecedented law. Close coordination with experts and civil society will be crucial to ensure that the act's interpretation and application mean that it is effective and consistent with the act's own articulated goals: protecting human rights, democracy, and the rule of law."

European Center for Not-for-Profit Law's Karolina Iwańska responded similarly: "Let's be clear: It has severe shortcomings from the point of view of fundamental rights and should not be treated as a golden standard for rights-based AI regulation. Having said that, we will work on the strongest possible implementation."

Yannis Vardakastanis, president of the European Disability Forum, said in a statement that "the AI Act addresses human rights, but not as comprehensively as we hoped for—we now call on the European Union to close this gap with future initiatives."

Amnesty's Hakobyan emphasized that "countries outside of the E.U. should learn from the bloc's failure to adequately regulate AI technologies and must not succumb to pressures by the technology industry and law enforcement authorities whilst developing regulation. States should instead put in place robust and binding AI legislation which prioritizes people and their rights."