For a while it looked like Guatemala was about to deliver justice.

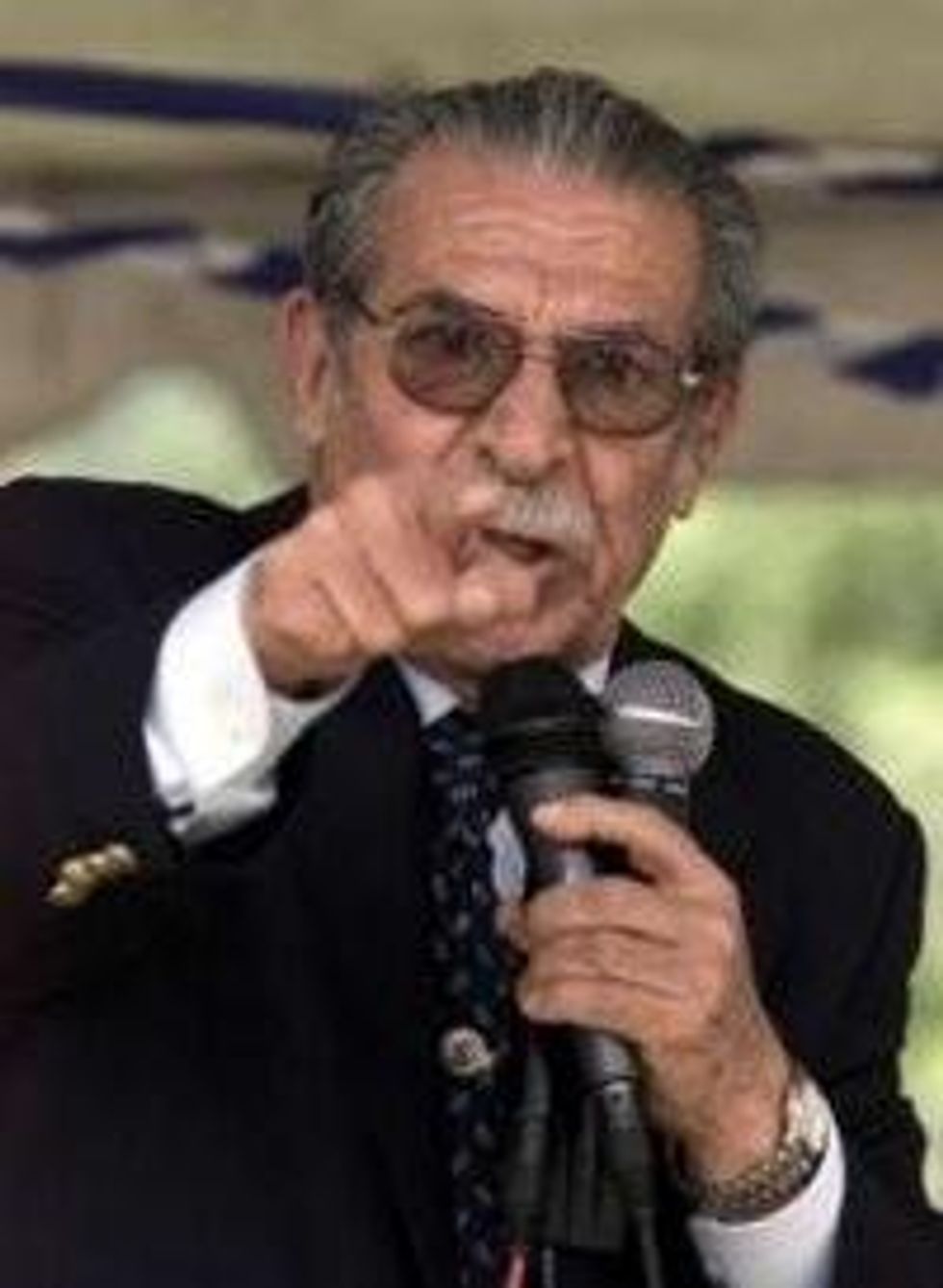

But the genocide case against General Efrain Rios Montt has just been suspended, hours before a criminal court was poised to deliver a verdict.

The last-second decision to kill the case was technically taken by an appeals court.

But behind the decision stands secret intervention by Guatemala's current president and death threats delivered to judges and prosecutors by associates of Guatemala's army.

Many dozens of Mayan massacre survivors risked their lives to testify. But now the court record they bravely created has been erased from above.

The following account of some of my personal knowledge of the case was written several days ago. I was asked to keep it private until a trial verdict had been reached:

"It would be mistaken to think that this case redounds to the credit of Guatemala's rulers.

It was forced upon them from below. The last thing they want is justice.

But they agreed to swallow a partial dose because political forces were such that they had to, and because they thought that they could get away with sacrificing Rios Montt to save their own skins.

I was called to testify in the Rios Montt case, was listed by the court as a 'qualified witness,' and was tentatively scheduled to testify on Monday, April 15. But at the last minute I was kept off the stand 'in order to avoid a confrontation with the [Guatemalan] executive.'

What that meant, I was given to understand, was that Gen. Otto Perez Molina, Guatemala's president, would shut down the case if I took the stand because my testimony could implicate him.

Beyond that, there was fear, concretely stated, that my taking the stand could lead to violence since given my past statements and writings I would implicate the 'institutional army.'

The bargain under which Perez Molina and the country's elite had let the case go forward was that it would only touch Rios Montt and his co-defendant, Gen. Mauricio Rodriguez Sanchez. The rest of the army would be spared, and likewise Perez Molina.

On that basis, Perez Molina, it was understood, would refrain from killing the Rios Montt trial case, and still more importantly would keep the old officer corps from killing prosecutors and witnesses, as well as hold off any hit squads that might be mounted by the the oligarchs of CACIF (the Chambers of Agriculture, Commerce, Industry and Finance). (Perez Molina has de facto power to kill the case via secret intervention with the Constitutional and other courts.)

This understanding was seen as vital to the survival of both the case and those involved in it. Army associates had already threatened the family of one of the lead prosecutors, and halfway through the trial a death threat had been delivered to one of the three presiding judges.

In the case of one of those threatened a man had offered him a bribe of one million US dollars as well as technical assistance with offshore accounts and laundering the funds. All the lawyer had to do was to agree to stop the Rios Montt case.

When that didn't work, the angle changed: the man put a pistol on the table and stated that he knew where to find the lawyer's children.

But so far no trial people had actually been killed. Though things were tense, the bargain was holding.

But to the shock of many and to world headlines in a press that had long under- and mis-reported Guatemala's terror, everything changed on April 5 when Hugo Ramiro Leonardo Reyes, a former army mechanic, testified by video from hiding that Perez Molina had ordered atrocities.

Testifying with his face half-covered by a baseball cap he recounted murders by Rios Montt's army and then unexpectedly added that one of the main perpetrators has been Perez Molina who he said had ordered executions and the destruction of villages.

This had occurred, he testified, during the massacres around Nebaj when Perez Molina was serving there as Rios Montt's field commander in 1982-83.

As it happened, I had also been there at that time and had encountered Perez Molina who was then living under the code name Major Tito Arias.

I had interviewed him on film several times. On one occasion we stood over the bodies of four captured guerrillas he had interrogated. Out of his earshot, Perez Molina's subordinates told me how, acting under orders, they routinely captured, tortured, and staged multiple executions of civilians.

The trial witness's broaching of Perez Molina's past evidently angered the President. He publicly denounced the witness and had him investigated.

He then summoned the Attorney General. The word went forth that if the trial case mentioned Perez Molina again, all previous understandings would be suspended. Canceling the Rios Montt case would be the least of their worries: there would be hell to pay.

The case went forward as originally agreed with Perez Molina. My testimony was cancelled, and the court record was kept clear of any additional evidence that could have further implicated the President.

Under Guatemalan law, a sitting President cannot be indicted. Perez Molina's term ends in 2016.

This is one small but revealing aspect of the case. The massacre story is not yet over."

After the above private account was written, Guatemala's army and oligarchy rallied. They started to feel that they had no political need to sacrifice Rios Montt. As Perez Molina heard from the elite, his and Rios Montt's interests converged.

On April 16 Perez Molina said publicly that the case was a threat to peace. On April 18, today, the Rios Montt genocide case was suspended.

(Regarding Background Sources: For some of my filmed inteviews with Perez Molina see the documentary Skoop! directed by Mikael Wahlforss. EPIDEM, Scandinavian television, 1983. Long excerpts from it, under the title Titulares de Hoy, are available on the website of Jean-Marie Simon who was my colleague on the film. Also see her photographs and narrative in her book Guatemala: Eternal Spring, Eternal Tyranny, W.W. Norton, 1988.

For a detailed contemporaneous report of the Rios Montt massacres see my piece in the April 11, 1983 The New Republic, "The Guns of Guatemala: The merciless mission of Rios Montt's army." The piece quotes some of Perez Molina's army subordinates and briefly mentions him as "Major Tito." At the time I wrote it and worked on the film I did not know his real name.

YouTube excerpts from the film went viral in Guatemala during Perez Molina's 2011 presidential campaign. During the campaign Perez Molina was evasive about whether he really was "Major Tito," though it later surfaced that he had admitted it years before but had then attempted to obscure that admission.

Also see my piece in the April 17, 1995 The Nation, "C.I.A. Death Squad: Americans have been directly involved in Guatemalan Army killings." The piece reports on US sponsorship of the G-2, the Guatemalan military intelligence unit which picked targets for assassination and disappearance and often did its own killings and torture. The piece names Perez Molina as one of "three of the recent G-2 chiefs [who] have been paid by the C.I.A., according to U.S. and Guatemalan intelligence sources."

The piece adds that then-Colonel "Perez Molina, who now runs the Presidential General Staff and oversees the Archivo, was in charge in 1994, when according to the Archbishop's human rights office, there was evidence of General Staff involvement in the assassination of Judge Edgar Ramiro Elias Ogaldez."

Likewise, at the time of The Nation article I still did not know that Perez Molina was Tito.

For one aspect of the US role in supporting Rios Montt see my Washington Post piece: "Despite Ban, U.S. Captain Trains Guatemalan Military," October 21, 1982, page 1.

After the 1983 New Republic piece the Guatemalan army sent an emissary who invited me to lunch at a fancy hotel and politely told me that I would be killed unless I retracted the article. The army murdered Guatemalans all the time, but for a US journalist the threat rang hollow. The man who delivered the threat later became an excellent source of information.)

Allan Nairn is an award-winning U.S. investigative journalist who became well-known when he was imprisoned by the Indonesian military while reporting in East Timor. His writings have focused on U.S. foreign policy in such countries as Haiti, Guatemala, Indonesia, and East Timor. In 1993, Nairn and Amy Goodman received the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial First Prize for International Radio award for their reporting on East Timor. In 1994, Nairn won the George Polk Award for Journalism for Magazine Reporting. Also in 1994, Nairn received the The James Aronson Award for Social Justice Journalism for his writing on Haiti for The Nation magazine.