SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Despite the widespread contamination from last year's Fukushima nuclear accident, the Obama administration's nuclear regulators have quietly weakened planning for emergency response to a major US nuclear power plant accident.

The Associated Press reports that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which run the program together, are now requiring fewer exercises for major accidents and recommending that fewer people be evacuated.

The latest changes, especially reduced evacuation zones, are being attacked by local planners and activists who say the widespread contamination in Japan from the Fukushima nuclear meltdowns screams out for stronger planning in the United States, not weaker rules.

In February, a national coalition of environmental and anti-nuclear groups had asked the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to expand evacuation planning from 10 miles to 25 miles and to broaden separate 50-mile readiness zones to 100 miles.

As America's nuclear power plants have aged, the once-rural areas around them have become far more crowded and much more difficult to evacuate. The population within 10 miles of San Onofre has ballooned by 283 percent to 98,631 since 1980.

* * *

The Associated Press reports:

Without fanfare, the nation's nuclear power regulators have overhauled community emergency planning for the first time in more than three decades, requiring fewer exercises for major accidents and recommending that fewer people be evacuated right away.

The revamp, the first since the program began after Three Mile Island in 1979, also eliminates a requirement that local responders always practice for a release of radiation.

The widespread contamination in Japan from last year's Fukushima nuclear accident screams out for stronger planning in the United States, not weaker rules.At least four years in the works, the changes appear to clash with more recent lessons of last year's reactor crisis in Japan. [...]

And some view as downright bizarre the idea that communities will now periodically run emergency scenarios without practicing for any significant release of radiation.

These changes, while documented in obscure federal publications, went into effect in December with hardly any notice by the general public.

An Associated Press investigative series in June exposed weaknesses in the U.S. emergency planning program. The stories detailed how many nuclear reactors are now operating beyond their design life under rules that have been relaxed to account for deteriorating safety margins. The series also documented considerable population growth around nuclear power plants and limitations in the scope of exercises. For example, local authorities assemble at command centers where they test communications, but they do not deploy around the community, reroute traffic or evacuate anyone as in a real emergency.

The latest changes, especially relaxed exercise plans for 50-mile emergency zones, are being flayed by some local planners and activists who say the widespread contamination in Japan from last year's Fukushima nuclear accident screams out for stronger planning in the United States, not weaker rules. [...]

None of the revisions has been questioned more than the new requirement that some planning exercises incorporate a reassuring premise: that no harmful radiation is released. Federal regulators say that conducting a wider variety of accident scenarios makes the exercises less predictable.

"We have the real business of protecting public health to do if we're not needed at an exercise," Texas radiation-monitoring specialist Robert Free wrote bluntly to federal regulators when they broached the idea. "Not to mention the waste of public monies."

Environmental and anti-nuclear activists also scoffed. "You need to be practicing for a worst case, rather than a nonevent," said nuclear policy analyst Jim Riccio of the group Greenpeace.[...]

While officials stress the importance of limiting radioactive releases, the revisions also favor limiting initial evacuations, even in a severe accident. Under the previous standard, people within two miles would be immediately evacuated, along with everyone five miles downwind. Now, in a large quick release of radioactivity, emergency personnel would concentrate first on evacuating people only within two miles. Others would be told to stay put and wait for a possible evacuation order later. [...]

This change, however, raises the likely severity of a panicked exodus outside the official evacuation area. Even a federal study used to shape the new program warns that up to 20 percent of people near official evacuation areas might also leave and potentially slow things down for everyone -- and that's assuming clear instructions.

"If it were me, I would evacuate" even without an official go-ahead, said Cheryl L. Chubb, a nuclear emergency planner with the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, who is critical of the changes.

At Fukushima, more than 150,000 people evacuated, including about 50,000 who left on their own, according to Japan's Education Ministry. At Three Mile Island, 195,000 people are estimated to have fled, though officials urged evacuation only for pregnant women and young children within five miles. About 135,000 people lived within 10 miles of the site at the time.

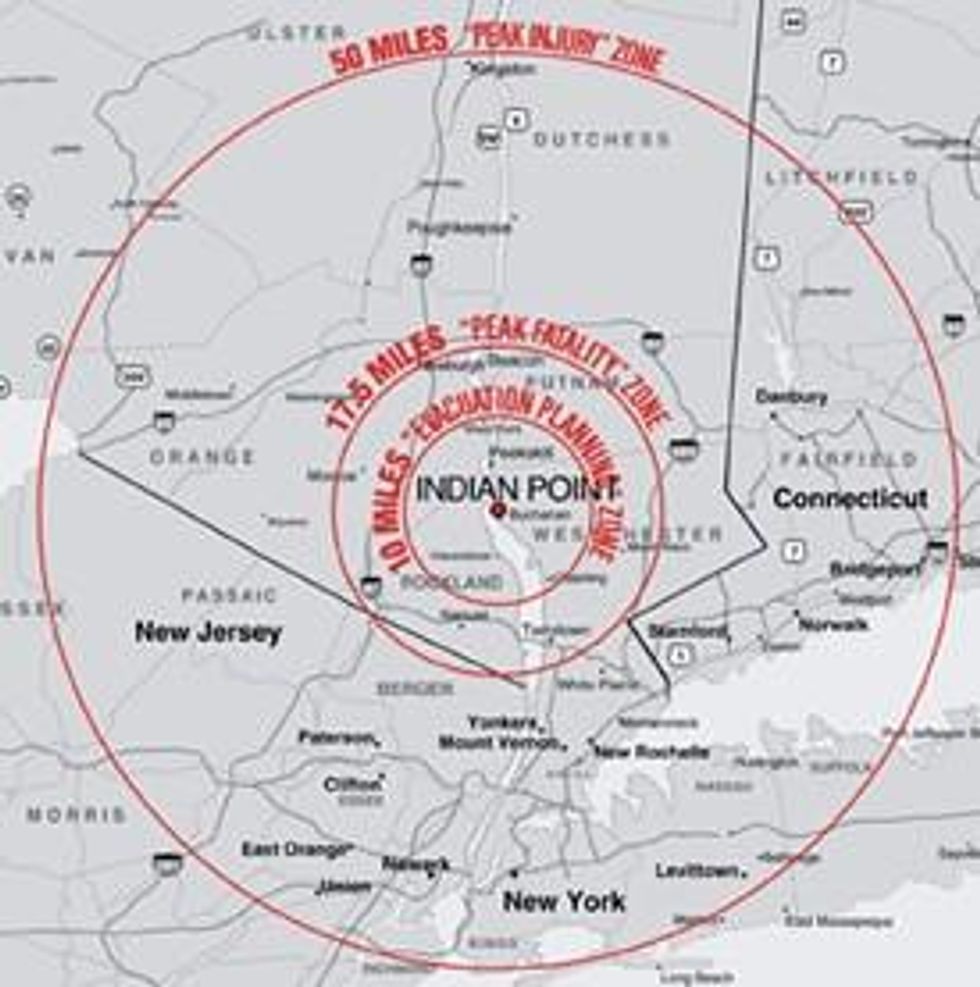

In its series, the AP reported that populations within 10 miles of U.S. nuclear sites have ballooned by as much as 4 1/2 times since 1980. Nuclear sites were originally picked in less populated areas to minimize the impact of accidents. Now, about 120 million Americans -- almost 40 percent -- live within 50 miles of a nuclear power plant, according to the AP's analysis of 2010 Census data. The Indian Point plant in Buchanan, N.Y., is at the center of the largest such zone, with 17.3 million people, including almost all of New York City.

"They're saying, 'If there's no way to evacuate, then we won't,'" Phillip Musegaas, a lawyer with the environmental group Riverkeeper, said of the stronger emphasis on taking shelter at home. The group is challenging relicensing of Indian Point.

In February, a national coalition of environmental and anti-nuclear groups asked the NRC to expand evacuation planning from 10 miles to 25 miles and to broaden separate 50-mile readiness zones to 100 miles. The groups also pressed for some exercises that simulate a nuclear accident accompanied by a natural disaster like an earthquake or hurricane -- akin to the combination of tsunami, blackout and meltdowns at Fukushima.

The new U.S. program has kept the 10- and 50-mile planning zones in place, as well as the requirement for one full exercise for a 10-mile evacuation every two years. However, required 50-mile planning exercises will now be held less often: every eight years, instead of every six years. [...]

The Japanese disaster reinforced such worries when officials told some towns beyond 12 miles from the disabled plant to evacuate. The U.S. government recommended that Americans stay at least 50 miles from the plant. Soil and crops were contaminated for scores of miles around. At one point, health authorities in Tokyo, 140 miles away, advised families not to give children the local water, which was contaminated by fallout to twice the government limit for infants.

* * *

# # #

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Despite the widespread contamination from last year's Fukushima nuclear accident, the Obama administration's nuclear regulators have quietly weakened planning for emergency response to a major US nuclear power plant accident.

The Associated Press reports that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which run the program together, are now requiring fewer exercises for major accidents and recommending that fewer people be evacuated.

The latest changes, especially reduced evacuation zones, are being attacked by local planners and activists who say the widespread contamination in Japan from the Fukushima nuclear meltdowns screams out for stronger planning in the United States, not weaker rules.

In February, a national coalition of environmental and anti-nuclear groups had asked the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to expand evacuation planning from 10 miles to 25 miles and to broaden separate 50-mile readiness zones to 100 miles.

As America's nuclear power plants have aged, the once-rural areas around them have become far more crowded and much more difficult to evacuate. The population within 10 miles of San Onofre has ballooned by 283 percent to 98,631 since 1980.

* * *

The Associated Press reports:

Without fanfare, the nation's nuclear power regulators have overhauled community emergency planning for the first time in more than three decades, requiring fewer exercises for major accidents and recommending that fewer people be evacuated right away.

The revamp, the first since the program began after Three Mile Island in 1979, also eliminates a requirement that local responders always practice for a release of radiation.

The widespread contamination in Japan from last year's Fukushima nuclear accident screams out for stronger planning in the United States, not weaker rules.At least four years in the works, the changes appear to clash with more recent lessons of last year's reactor crisis in Japan. [...]

And some view as downright bizarre the idea that communities will now periodically run emergency scenarios without practicing for any significant release of radiation.

These changes, while documented in obscure federal publications, went into effect in December with hardly any notice by the general public.

An Associated Press investigative series in June exposed weaknesses in the U.S. emergency planning program. The stories detailed how many nuclear reactors are now operating beyond their design life under rules that have been relaxed to account for deteriorating safety margins. The series also documented considerable population growth around nuclear power plants and limitations in the scope of exercises. For example, local authorities assemble at command centers where they test communications, but they do not deploy around the community, reroute traffic or evacuate anyone as in a real emergency.

The latest changes, especially relaxed exercise plans for 50-mile emergency zones, are being flayed by some local planners and activists who say the widespread contamination in Japan from last year's Fukushima nuclear accident screams out for stronger planning in the United States, not weaker rules. [...]

None of the revisions has been questioned more than the new requirement that some planning exercises incorporate a reassuring premise: that no harmful radiation is released. Federal regulators say that conducting a wider variety of accident scenarios makes the exercises less predictable.

"We have the real business of protecting public health to do if we're not needed at an exercise," Texas radiation-monitoring specialist Robert Free wrote bluntly to federal regulators when they broached the idea. "Not to mention the waste of public monies."

Environmental and anti-nuclear activists also scoffed. "You need to be practicing for a worst case, rather than a nonevent," said nuclear policy analyst Jim Riccio of the group Greenpeace.[...]

While officials stress the importance of limiting radioactive releases, the revisions also favor limiting initial evacuations, even in a severe accident. Under the previous standard, people within two miles would be immediately evacuated, along with everyone five miles downwind. Now, in a large quick release of radioactivity, emergency personnel would concentrate first on evacuating people only within two miles. Others would be told to stay put and wait for a possible evacuation order later. [...]

This change, however, raises the likely severity of a panicked exodus outside the official evacuation area. Even a federal study used to shape the new program warns that up to 20 percent of people near official evacuation areas might also leave and potentially slow things down for everyone -- and that's assuming clear instructions.

"If it were me, I would evacuate" even without an official go-ahead, said Cheryl L. Chubb, a nuclear emergency planner with the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, who is critical of the changes.

At Fukushima, more than 150,000 people evacuated, including about 50,000 who left on their own, according to Japan's Education Ministry. At Three Mile Island, 195,000 people are estimated to have fled, though officials urged evacuation only for pregnant women and young children within five miles. About 135,000 people lived within 10 miles of the site at the time.

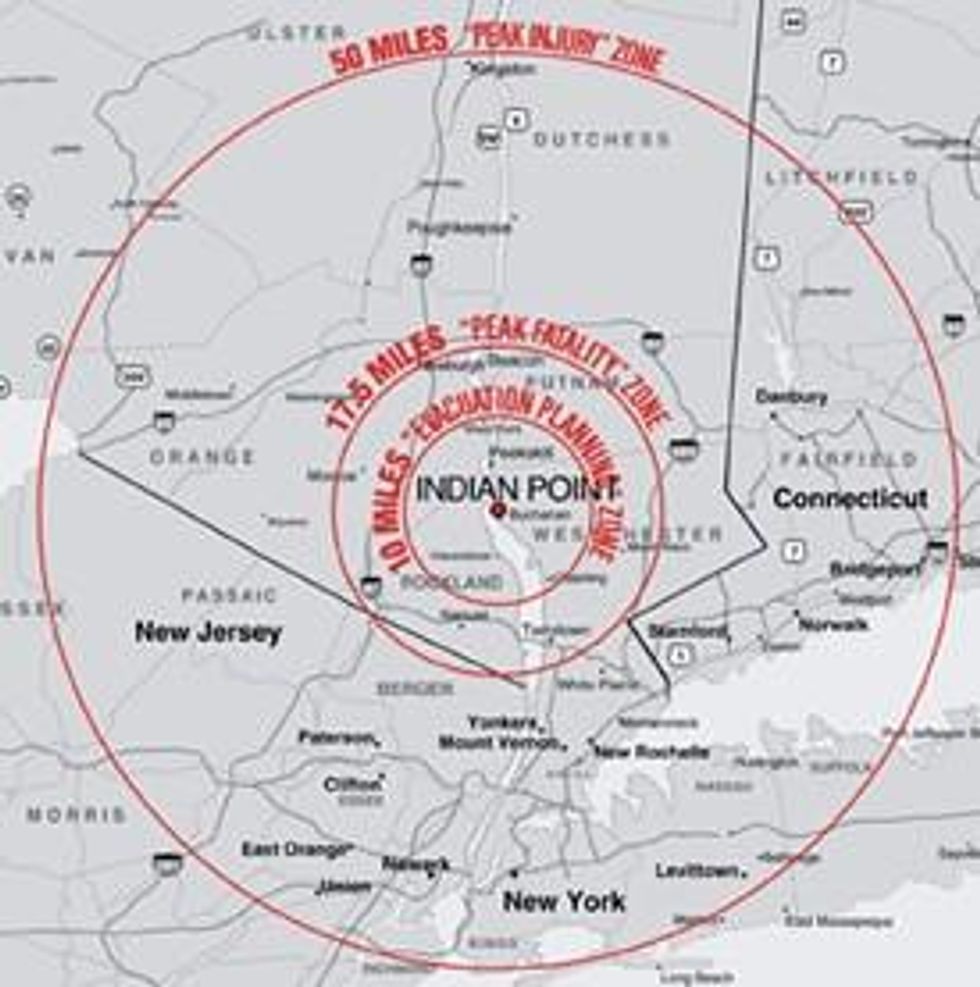

In its series, the AP reported that populations within 10 miles of U.S. nuclear sites have ballooned by as much as 4 1/2 times since 1980. Nuclear sites were originally picked in less populated areas to minimize the impact of accidents. Now, about 120 million Americans -- almost 40 percent -- live within 50 miles of a nuclear power plant, according to the AP's analysis of 2010 Census data. The Indian Point plant in Buchanan, N.Y., is at the center of the largest such zone, with 17.3 million people, including almost all of New York City.

"They're saying, 'If there's no way to evacuate, then we won't,'" Phillip Musegaas, a lawyer with the environmental group Riverkeeper, said of the stronger emphasis on taking shelter at home. The group is challenging relicensing of Indian Point.

In February, a national coalition of environmental and anti-nuclear groups asked the NRC to expand evacuation planning from 10 miles to 25 miles and to broaden separate 50-mile readiness zones to 100 miles. The groups also pressed for some exercises that simulate a nuclear accident accompanied by a natural disaster like an earthquake or hurricane -- akin to the combination of tsunami, blackout and meltdowns at Fukushima.

The new U.S. program has kept the 10- and 50-mile planning zones in place, as well as the requirement for one full exercise for a 10-mile evacuation every two years. However, required 50-mile planning exercises will now be held less often: every eight years, instead of every six years. [...]

The Japanese disaster reinforced such worries when officials told some towns beyond 12 miles from the disabled plant to evacuate. The U.S. government recommended that Americans stay at least 50 miles from the plant. Soil and crops were contaminated for scores of miles around. At one point, health authorities in Tokyo, 140 miles away, advised families not to give children the local water, which was contaminated by fallout to twice the government limit for infants.

* * *

# # #

Despite the widespread contamination from last year's Fukushima nuclear accident, the Obama administration's nuclear regulators have quietly weakened planning for emergency response to a major US nuclear power plant accident.

The Associated Press reports that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which run the program together, are now requiring fewer exercises for major accidents and recommending that fewer people be evacuated.

The latest changes, especially reduced evacuation zones, are being attacked by local planners and activists who say the widespread contamination in Japan from the Fukushima nuclear meltdowns screams out for stronger planning in the United States, not weaker rules.

In February, a national coalition of environmental and anti-nuclear groups had asked the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to expand evacuation planning from 10 miles to 25 miles and to broaden separate 50-mile readiness zones to 100 miles.

As America's nuclear power plants have aged, the once-rural areas around them have become far more crowded and much more difficult to evacuate. The population within 10 miles of San Onofre has ballooned by 283 percent to 98,631 since 1980.

* * *

The Associated Press reports:

Without fanfare, the nation's nuclear power regulators have overhauled community emergency planning for the first time in more than three decades, requiring fewer exercises for major accidents and recommending that fewer people be evacuated right away.

The revamp, the first since the program began after Three Mile Island in 1979, also eliminates a requirement that local responders always practice for a release of radiation.

The widespread contamination in Japan from last year's Fukushima nuclear accident screams out for stronger planning in the United States, not weaker rules.At least four years in the works, the changes appear to clash with more recent lessons of last year's reactor crisis in Japan. [...]

And some view as downright bizarre the idea that communities will now periodically run emergency scenarios without practicing for any significant release of radiation.

These changes, while documented in obscure federal publications, went into effect in December with hardly any notice by the general public.

An Associated Press investigative series in June exposed weaknesses in the U.S. emergency planning program. The stories detailed how many nuclear reactors are now operating beyond their design life under rules that have been relaxed to account for deteriorating safety margins. The series also documented considerable population growth around nuclear power plants and limitations in the scope of exercises. For example, local authorities assemble at command centers where they test communications, but they do not deploy around the community, reroute traffic or evacuate anyone as in a real emergency.

The latest changes, especially relaxed exercise plans for 50-mile emergency zones, are being flayed by some local planners and activists who say the widespread contamination in Japan from last year's Fukushima nuclear accident screams out for stronger planning in the United States, not weaker rules. [...]

None of the revisions has been questioned more than the new requirement that some planning exercises incorporate a reassuring premise: that no harmful radiation is released. Federal regulators say that conducting a wider variety of accident scenarios makes the exercises less predictable.

"We have the real business of protecting public health to do if we're not needed at an exercise," Texas radiation-monitoring specialist Robert Free wrote bluntly to federal regulators when they broached the idea. "Not to mention the waste of public monies."

Environmental and anti-nuclear activists also scoffed. "You need to be practicing for a worst case, rather than a nonevent," said nuclear policy analyst Jim Riccio of the group Greenpeace.[...]

While officials stress the importance of limiting radioactive releases, the revisions also favor limiting initial evacuations, even in a severe accident. Under the previous standard, people within two miles would be immediately evacuated, along with everyone five miles downwind. Now, in a large quick release of radioactivity, emergency personnel would concentrate first on evacuating people only within two miles. Others would be told to stay put and wait for a possible evacuation order later. [...]

This change, however, raises the likely severity of a panicked exodus outside the official evacuation area. Even a federal study used to shape the new program warns that up to 20 percent of people near official evacuation areas might also leave and potentially slow things down for everyone -- and that's assuming clear instructions.

"If it were me, I would evacuate" even without an official go-ahead, said Cheryl L. Chubb, a nuclear emergency planner with the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, who is critical of the changes.

At Fukushima, more than 150,000 people evacuated, including about 50,000 who left on their own, according to Japan's Education Ministry. At Three Mile Island, 195,000 people are estimated to have fled, though officials urged evacuation only for pregnant women and young children within five miles. About 135,000 people lived within 10 miles of the site at the time.

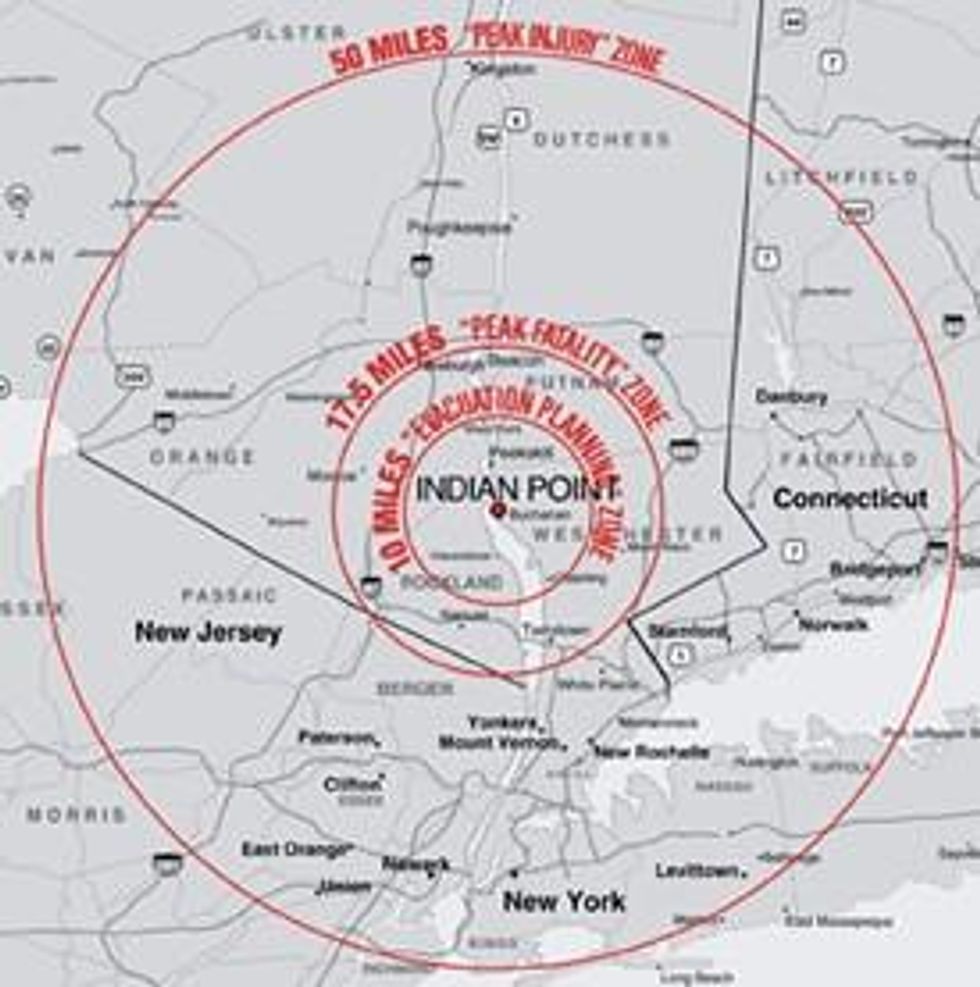

In its series, the AP reported that populations within 10 miles of U.S. nuclear sites have ballooned by as much as 4 1/2 times since 1980. Nuclear sites were originally picked in less populated areas to minimize the impact of accidents. Now, about 120 million Americans -- almost 40 percent -- live within 50 miles of a nuclear power plant, according to the AP's analysis of 2010 Census data. The Indian Point plant in Buchanan, N.Y., is at the center of the largest such zone, with 17.3 million people, including almost all of New York City.

"They're saying, 'If there's no way to evacuate, then we won't,'" Phillip Musegaas, a lawyer with the environmental group Riverkeeper, said of the stronger emphasis on taking shelter at home. The group is challenging relicensing of Indian Point.

In February, a national coalition of environmental and anti-nuclear groups asked the NRC to expand evacuation planning from 10 miles to 25 miles and to broaden separate 50-mile readiness zones to 100 miles. The groups also pressed for some exercises that simulate a nuclear accident accompanied by a natural disaster like an earthquake or hurricane -- akin to the combination of tsunami, blackout and meltdowns at Fukushima.

The new U.S. program has kept the 10- and 50-mile planning zones in place, as well as the requirement for one full exercise for a 10-mile evacuation every two years. However, required 50-mile planning exercises will now be held less often: every eight years, instead of every six years. [...]

The Japanese disaster reinforced such worries when officials told some towns beyond 12 miles from the disabled plant to evacuate. The U.S. government recommended that Americans stay at least 50 miles from the plant. Soil and crops were contaminated for scores of miles around. At one point, health authorities in Tokyo, 140 miles away, advised families not to give children the local water, which was contaminated by fallout to twice the government limit for infants.

* * *

# # #