SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

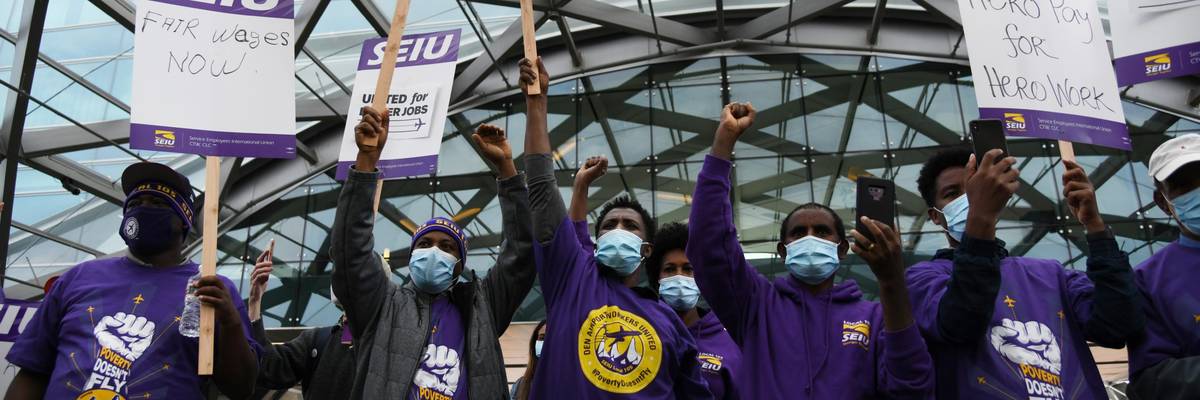

Seleshi Haile, front center, and hundreds of Denver International Airport janitors walked off the job, striking for higher pay and less taxing workload at Denver International Airport in Denver, Colorado on Friday, October 1, 2021. (Photo: Hyoung Chang/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

Many in the media are very upset that workers at the bottom end of the pay scale feel secure enough to demand higher pay and better working conditions. Yesterday, I had the pleasure of watching a television anchor, who earns $6 million a year, complain that 3 percent of the workforce quit their job in August. They seemed to find the idea of workers quitting unsatisfactory jobs appalling.

After decades of wage stagnation for those at the middle and the bottom of the wage ladder, it's good to see some real progress for at least some low-paid workers.

For those of us who think that all workers should be able to get decent pay, have decent working conditions, and be treated with respect on the job, the idea that large numbers of workers now feel they can quit jobs they don't like is really great news. And, the increased labor market power for those at the bottom of the ladder is showing up in higher pay.

Here's the story for production and non-supervisory workers in six of the lowest-paying industries. Note, these numbers are adjusted for inflation, so they take account of the extent to which higher prices have reduced purchasing power since the start of the pandemic.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author's calculations.

The biggest gains were for workers in hotels and convenience stores who have seen their inflation-adjusted hourly wage increase by 9.0 percent and 8.6 percent, respectively, since the pandemic began. Workers in restaurants have seen their hourly pay rise by 5.6 percent, while workers in nursing homes have seen their pay rise by 4.6 percent. Child care and home health care workers have seen much more limited inflation-adjusted wage gains, getting increases of 1.9 percent and 1.4 percent, respectively.

It is important to remember that these gains are over just a one-and-a-half-year period. These workers have a long way to go before they have anything resembling a livable wage, but this is impressive progress in at least some of these low-paying industries.

There has been a sharp drop in employment in both home health care and child care since the start of the pandemic. These sectors will have a hard time getting back workers unless they can offer better pay and conditions. That will be difficult for them to do without more government support, pointing again to the importance of Biden's Build Back Better agenda.

In any case, after decades of wage stagnation for those at the middle and the bottom of the wage ladder, it's good to see some real progress for at least some low-paid workers. The folks who have rigged the economy in their favor so they can get big bucks may not like the fact that it's harder to get good help, but them's the breaks.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Many in the media are very upset that workers at the bottom end of the pay scale feel secure enough to demand higher pay and better working conditions. Yesterday, I had the pleasure of watching a television anchor, who earns $6 million a year, complain that 3 percent of the workforce quit their job in August. They seemed to find the idea of workers quitting unsatisfactory jobs appalling.

After decades of wage stagnation for those at the middle and the bottom of the wage ladder, it's good to see some real progress for at least some low-paid workers.

For those of us who think that all workers should be able to get decent pay, have decent working conditions, and be treated with respect on the job, the idea that large numbers of workers now feel they can quit jobs they don't like is really great news. And, the increased labor market power for those at the bottom of the ladder is showing up in higher pay.

Here's the story for production and non-supervisory workers in six of the lowest-paying industries. Note, these numbers are adjusted for inflation, so they take account of the extent to which higher prices have reduced purchasing power since the start of the pandemic.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author's calculations.

The biggest gains were for workers in hotels and convenience stores who have seen their inflation-adjusted hourly wage increase by 9.0 percent and 8.6 percent, respectively, since the pandemic began. Workers in restaurants have seen their hourly pay rise by 5.6 percent, while workers in nursing homes have seen their pay rise by 4.6 percent. Child care and home health care workers have seen much more limited inflation-adjusted wage gains, getting increases of 1.9 percent and 1.4 percent, respectively.

It is important to remember that these gains are over just a one-and-a-half-year period. These workers have a long way to go before they have anything resembling a livable wage, but this is impressive progress in at least some of these low-paying industries.

There has been a sharp drop in employment in both home health care and child care since the start of the pandemic. These sectors will have a hard time getting back workers unless they can offer better pay and conditions. That will be difficult for them to do without more government support, pointing again to the importance of Biden's Build Back Better agenda.

In any case, after decades of wage stagnation for those at the middle and the bottom of the wage ladder, it's good to see some real progress for at least some low-paid workers. The folks who have rigged the economy in their favor so they can get big bucks may not like the fact that it's harder to get good help, but them's the breaks.

Many in the media are very upset that workers at the bottom end of the pay scale feel secure enough to demand higher pay and better working conditions. Yesterday, I had the pleasure of watching a television anchor, who earns $6 million a year, complain that 3 percent of the workforce quit their job in August. They seemed to find the idea of workers quitting unsatisfactory jobs appalling.

After decades of wage stagnation for those at the middle and the bottom of the wage ladder, it's good to see some real progress for at least some low-paid workers.

For those of us who think that all workers should be able to get decent pay, have decent working conditions, and be treated with respect on the job, the idea that large numbers of workers now feel they can quit jobs they don't like is really great news. And, the increased labor market power for those at the bottom of the ladder is showing up in higher pay.

Here's the story for production and non-supervisory workers in six of the lowest-paying industries. Note, these numbers are adjusted for inflation, so they take account of the extent to which higher prices have reduced purchasing power since the start of the pandemic.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author's calculations.

The biggest gains were for workers in hotels and convenience stores who have seen their inflation-adjusted hourly wage increase by 9.0 percent and 8.6 percent, respectively, since the pandemic began. Workers in restaurants have seen their hourly pay rise by 5.6 percent, while workers in nursing homes have seen their pay rise by 4.6 percent. Child care and home health care workers have seen much more limited inflation-adjusted wage gains, getting increases of 1.9 percent and 1.4 percent, respectively.

It is important to remember that these gains are over just a one-and-a-half-year period. These workers have a long way to go before they have anything resembling a livable wage, but this is impressive progress in at least some of these low-paying industries.

There has been a sharp drop in employment in both home health care and child care since the start of the pandemic. These sectors will have a hard time getting back workers unless they can offer better pay and conditions. That will be difficult for them to do without more government support, pointing again to the importance of Biden's Build Back Better agenda.

In any case, after decades of wage stagnation for those at the middle and the bottom of the wage ladder, it's good to see some real progress for at least some low-paid workers. The folks who have rigged the economy in their favor so they can get big bucks may not like the fact that it's harder to get good help, but them's the breaks.