SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) workers in New York City were among those on the early frontlines of the national coronavirus pandemic when it first struck in March of 2020. (Photo: Andrew Cashin / MTA New York City Transit / flickr / cc)

Dr. Kenneth Olden, former Director of the Howard University Cancer Center (1985-1991), Director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (1991-2005), founding Dean of School of Public Health, City University of New York (2008-2012), and an African-American who grew up dirt poor in Parrotsville, Tennessee, has a message for us.

" Economic inequality is the key to understanding this country's public health problems and the COVID-19 crisis in particular," he told me in an interview earlier this month. "The poorer you are the more your health is at risk. Focusing on the class dimension also helps us build coalitions among lower income people of all colors and ethnicities."

Do the facts back up Dr. Olden's claim about COVID-19?

The answers do not come easily because in the U.S. official COVID-19 illness data--which you can see here--is collected without reference to occupation or income. As a result, media accounts tend to conflate being poor with being African-American or Hispanic.

To gain a more accurate approximation, we use statistical measures of neighborhoods (census tracts) to estimate the independent impacts of race, class, age, housing conditions, and immigration status on who is likely to die from the virus. At the Labor Institute, we have compiled and tested four data sets encompassing positive test and death rates in New York City, and deaths rates in Chicago and Los Angeles. While our results are only statistical estimates due to the lack of direct income/occupational data for each COVID-19 fatality, the findings strongly suggest that Dr. Olden is correct: Income has an enormous impact on who gets sick and who dies.

New York City Revisited

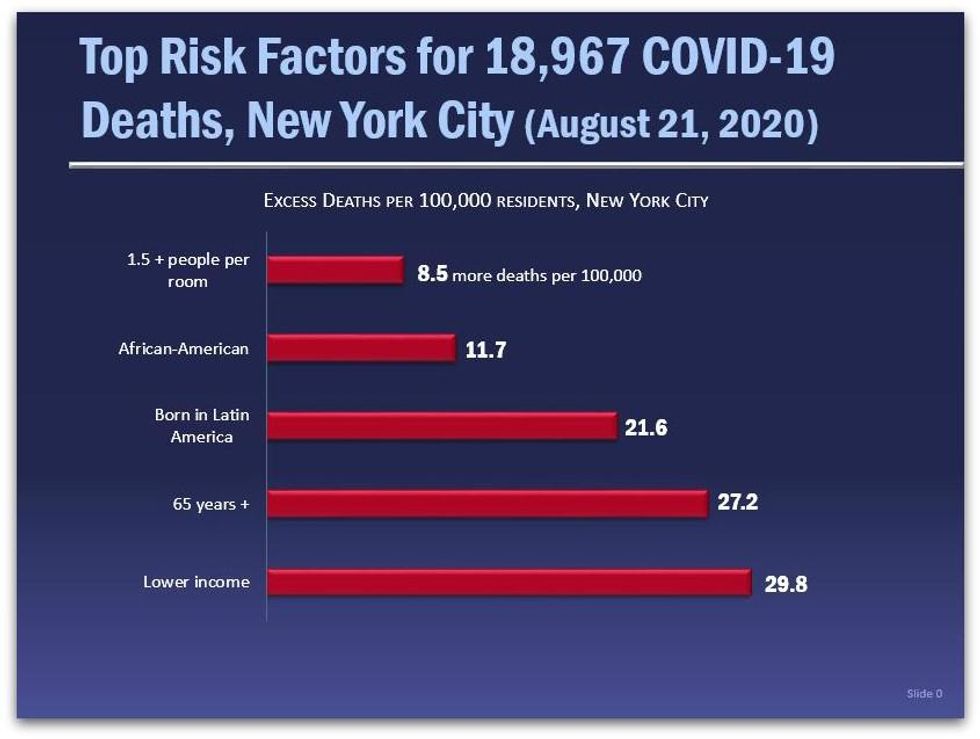

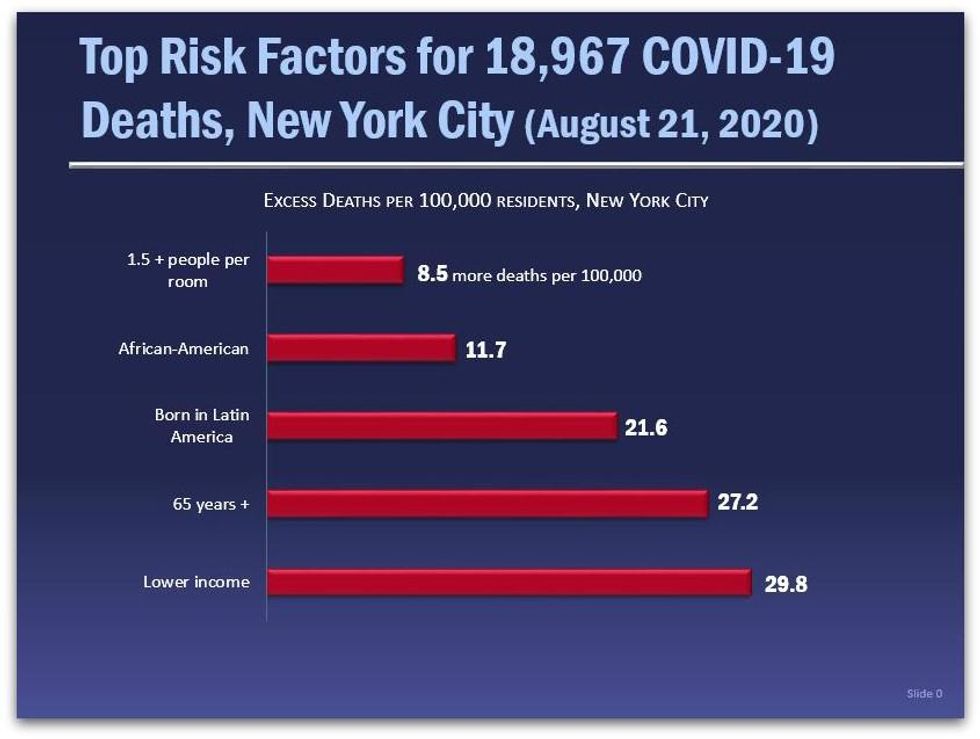

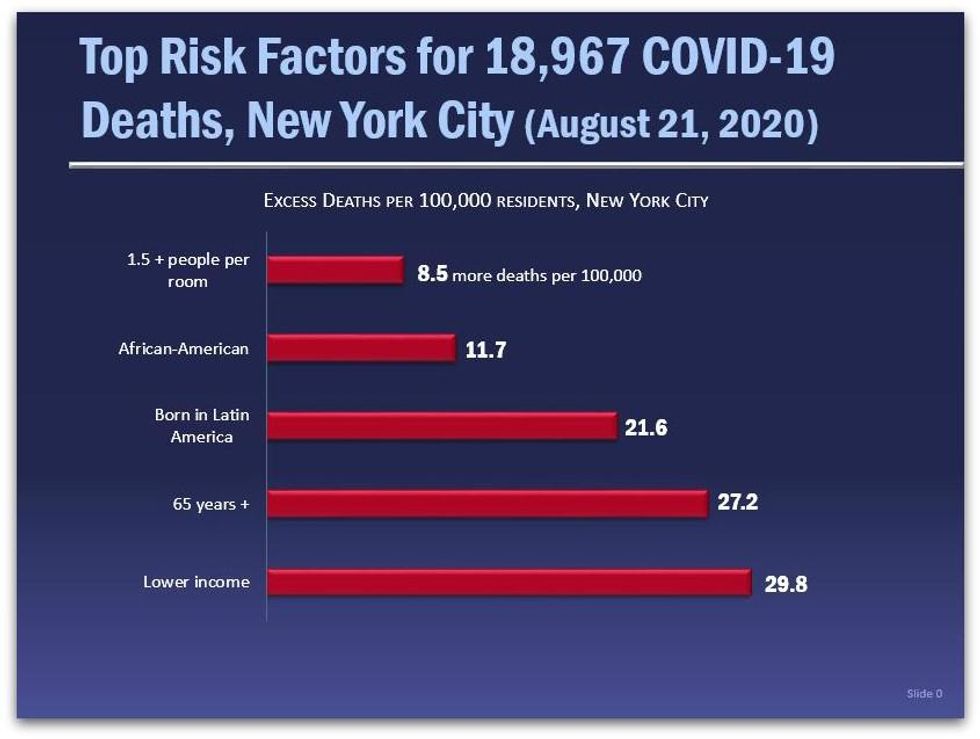

Our initial New York City report, "COVID's Class War" (July 28, 2020) shows that neighborhood median income has the strongest correlation with COVID-19 death rates per zip code. Since then, NYC has released more data for a total of 18,967 deaths by zip code as of August 21. Please note, the average NYC census tract neighborhood in our data base is 41.9% white, 27.3% Hispanic (19.1% born in Latin America), 25.7% Black, 14.3% Asian, 14.3% aged 65 and older, and 1.3% of households with 1.5 or more people per room.

We reran our regression model on this new data, and again the results show that those who live in a neighborhood that is about 1/3 poorer (one standard deviation) than the average New York City neighborhood would face the highest risk of dying from COVID-19, followed closely by age and being born in Latin America (a strong though certainly imperfect proxy for working-class immigrants, including undocumented residents.) Because these results are independent of each other, this data also suggests that the combination of these factors--like being a lower income, elderly immigrant, living in crowded housing--would greatly increase the risk.*

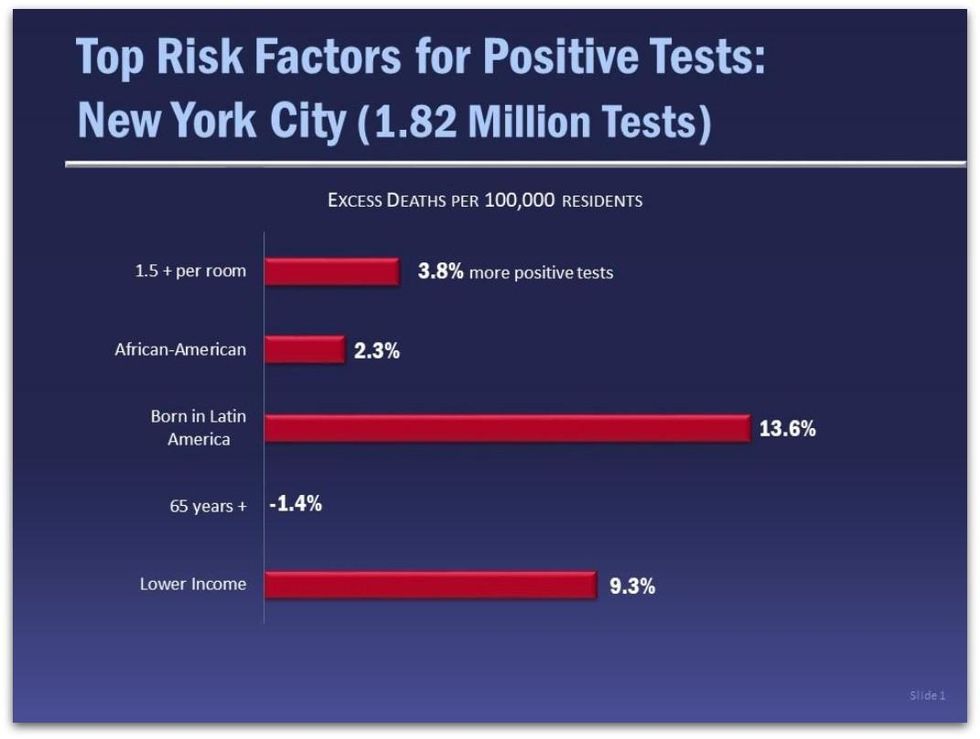

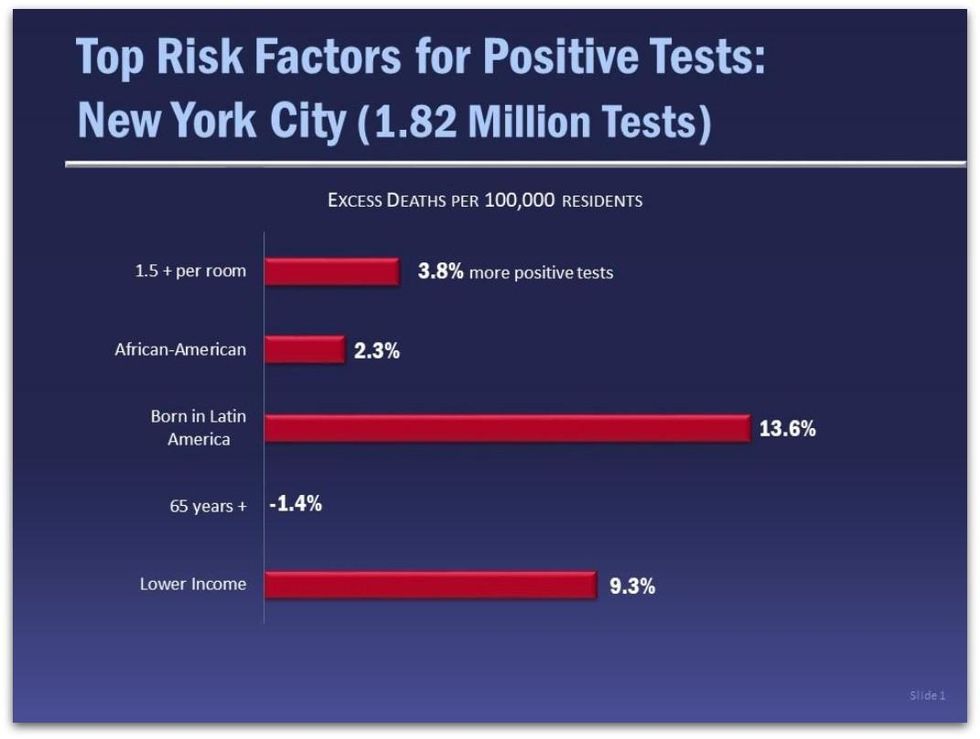

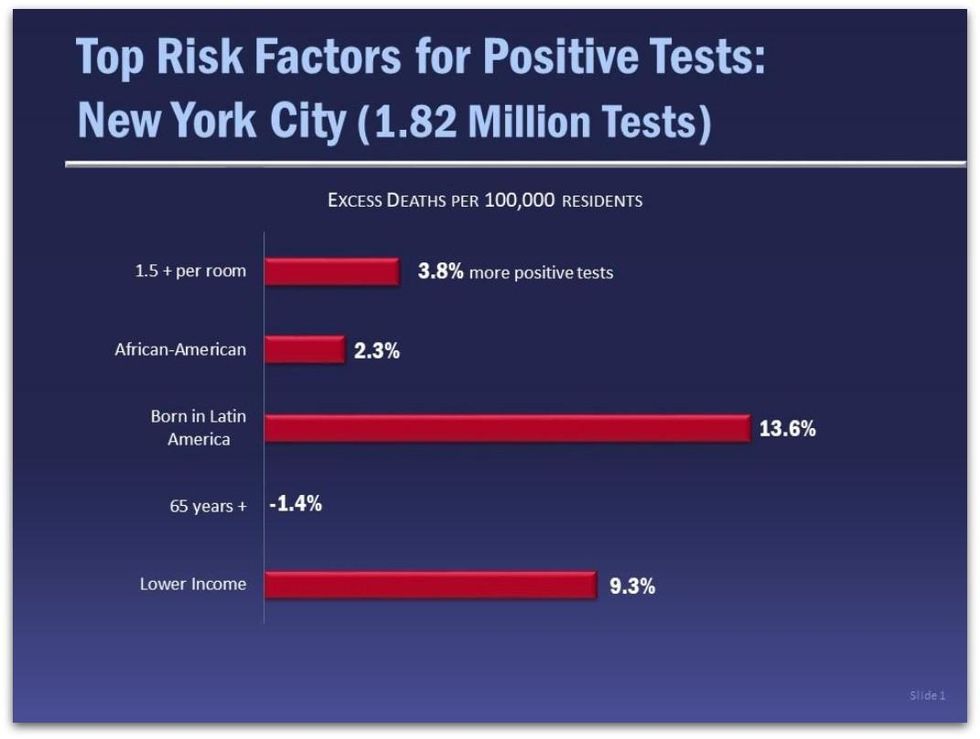

This updated NYC database for the first time also has the percentages of positive COVID-19 deaths per zip code covering more than 1.5 million tests. Our multiple regression reveals** that neighborhoods with about one-third more residents who were born in Latin America faced the most risk with 13.6 percent more positive test results than the average New York neighborhood. Poorer neighborhoods had a 9.3 percent higher rate than an average income neighborhood. It is not difficult to understand that recent immigrants, especially if undocumented, are far less likely to engage with official public health structures until they have no choice for fear of being deported. At the same time they are ineligible for federal benefits and are far more likely to be out in public, either engaged in work or seeking work.

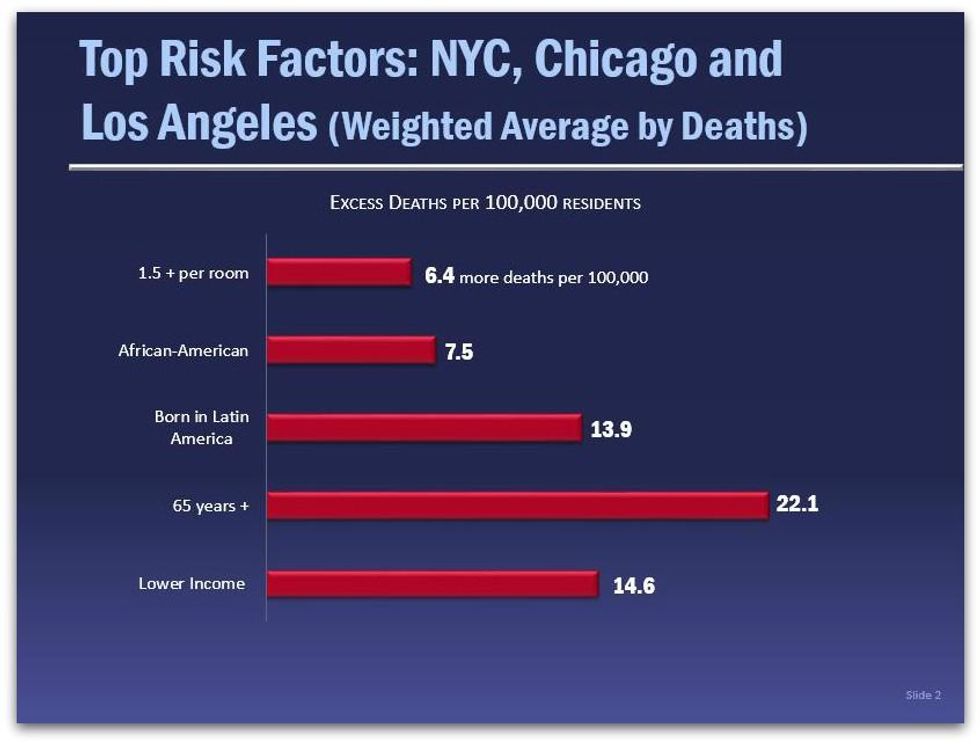

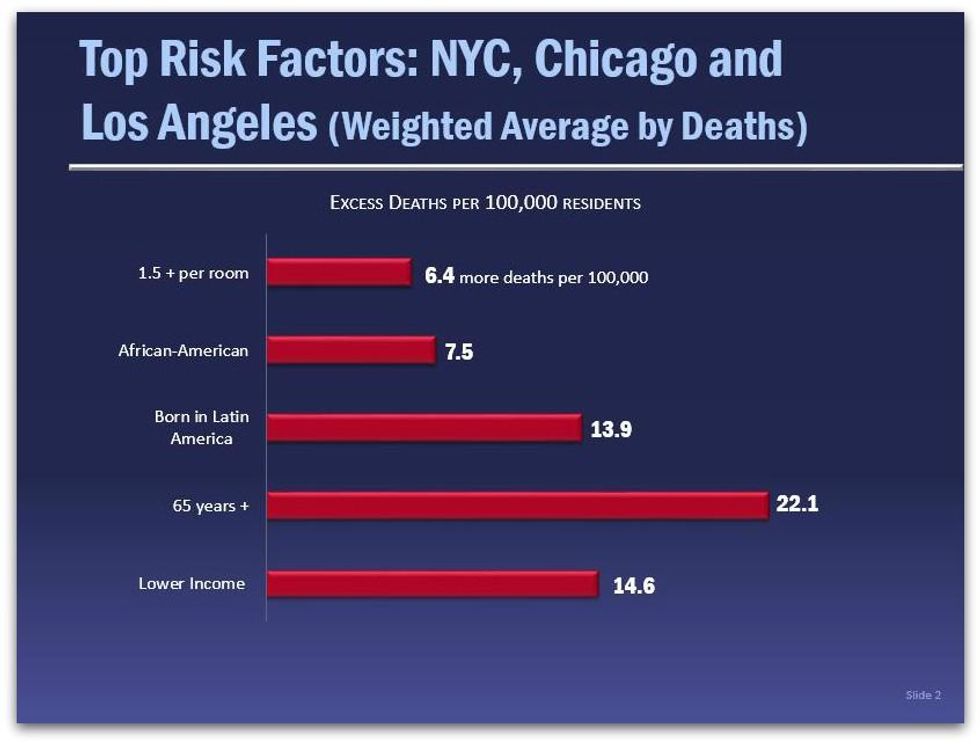

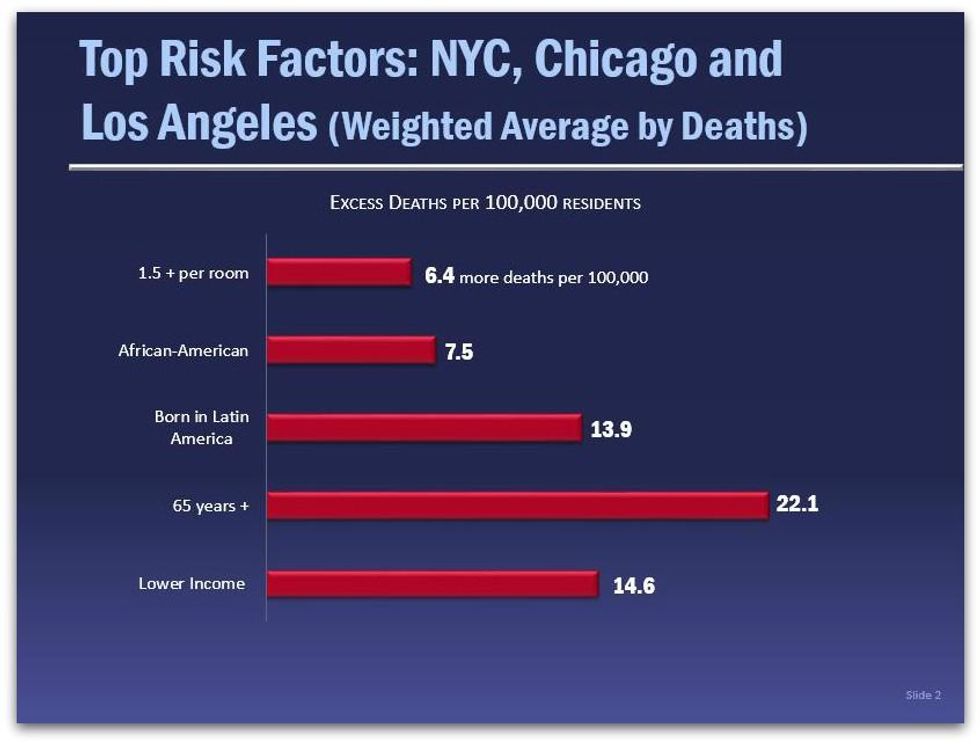

In addition to the 18,967 COVID-19 deaths in our NYC data base, we ran regressions on our Chicago data set (4,400 deaths), and for Los Angeles (5,689 deaths.) The table below provides a weighted average based on the number of COVID-19 deaths in each of the three cities. Again, the results confirm a prominent role for income in estimating COVID-19 death rates.

Class within Race

The relative power of income as the top risk factor should come as no surprise given that lower income people most often must work away from home in order to survive, often in "essential" employment with a higher risk of virus exposure. Another reason may be connected to the enormous wealth and class disparities within racial, ethnic, and age categories. Not only has systematic racism over the generations disproportionately congregated black and brown working people in the lowest wage jobs, but also systematic runaway inequality in the last 40 years has created enormous wealth extremes between the rich and everyone else within all populations, according to data compiled by Matt Bruenig at the People's Policy Project:

These studies also point out that while the vast majority of our nation's wealth is owned by wealthy whites, "The bottom half of society, which together own just 1.5 percent of the wealth, is thoroughly multiracial with whites making up a slim majority."

While overall the white/black wealth gap on average is almost 7 to 1, there is no racial gap for the bottom 20% of the population--both black and white in the lowest quintile have no wealth at all, according to a report from the Brookings Institution.

This reinforces Dr. Olden's primary political concern: How do we build a coalition of common interest powerful enough to create a healthier society that dramatically reduces poverty? Our COVID-19 data suggests that one focus should be on building solidarity among the vast majority of us who must struggle to make ends meet. It would be worthwhile to do what Dr. Olden has done all his life--build class solidarity while also fighting against racial discrimination in all its forms.

Notes:

* The independent variables used in all five multiple regressions have p scores below .01%, and each variable has a low VIF score reducing the likelihood of multicolinearity. The r squared scores are as follows: NYC deaths 27%; NYC tests, 56%; Chicago deaths, 20%; and Los Angeles deaths, 21%. The number of observations are: NYC, 2,052; Chicago, 4,405; and Los Angeles, 2,272.

** Peter Kreutzer provided extensive research assistance, while Michael Parkin, Professor of Politics, Oberlin College, graciously answered all our questions concerning the regressions. Any statistical errors are of our making, not Professor Parkin's.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Les Leopold is the executive director of the Labor Institute and author of the new book, “Wall Street’s War on Workers: How Mass Layoffs and Greed Are Destroying the Working Class and What to Do About It." (2024). Read more of his work on his substack here.

Dr. Kenneth Olden, former Director of the Howard University Cancer Center (1985-1991), Director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (1991-2005), founding Dean of School of Public Health, City University of New York (2008-2012), and an African-American who grew up dirt poor in Parrotsville, Tennessee, has a message for us.

" Economic inequality is the key to understanding this country's public health problems and the COVID-19 crisis in particular," he told me in an interview earlier this month. "The poorer you are the more your health is at risk. Focusing on the class dimension also helps us build coalitions among lower income people of all colors and ethnicities."

Do the facts back up Dr. Olden's claim about COVID-19?

The answers do not come easily because in the U.S. official COVID-19 illness data--which you can see here--is collected without reference to occupation or income. As a result, media accounts tend to conflate being poor with being African-American or Hispanic.

To gain a more accurate approximation, we use statistical measures of neighborhoods (census tracts) to estimate the independent impacts of race, class, age, housing conditions, and immigration status on who is likely to die from the virus. At the Labor Institute, we have compiled and tested four data sets encompassing positive test and death rates in New York City, and deaths rates in Chicago and Los Angeles. While our results are only statistical estimates due to the lack of direct income/occupational data for each COVID-19 fatality, the findings strongly suggest that Dr. Olden is correct: Income has an enormous impact on who gets sick and who dies.

New York City Revisited

Our initial New York City report, "COVID's Class War" (July 28, 2020) shows that neighborhood median income has the strongest correlation with COVID-19 death rates per zip code. Since then, NYC has released more data for a total of 18,967 deaths by zip code as of August 21. Please note, the average NYC census tract neighborhood in our data base is 41.9% white, 27.3% Hispanic (19.1% born in Latin America), 25.7% Black, 14.3% Asian, 14.3% aged 65 and older, and 1.3% of households with 1.5 or more people per room.

We reran our regression model on this new data, and again the results show that those who live in a neighborhood that is about 1/3 poorer (one standard deviation) than the average New York City neighborhood would face the highest risk of dying from COVID-19, followed closely by age and being born in Latin America (a strong though certainly imperfect proxy for working-class immigrants, including undocumented residents.) Because these results are independent of each other, this data also suggests that the combination of these factors--like being a lower income, elderly immigrant, living in crowded housing--would greatly increase the risk.*

This updated NYC database for the first time also has the percentages of positive COVID-19 deaths per zip code covering more than 1.5 million tests. Our multiple regression reveals** that neighborhoods with about one-third more residents who were born in Latin America faced the most risk with 13.6 percent more positive test results than the average New York neighborhood. Poorer neighborhoods had a 9.3 percent higher rate than an average income neighborhood. It is not difficult to understand that recent immigrants, especially if undocumented, are far less likely to engage with official public health structures until they have no choice for fear of being deported. At the same time they are ineligible for federal benefits and are far more likely to be out in public, either engaged in work or seeking work.

In addition to the 18,967 COVID-19 deaths in our NYC data base, we ran regressions on our Chicago data set (4,400 deaths), and for Los Angeles (5,689 deaths.) The table below provides a weighted average based on the number of COVID-19 deaths in each of the three cities. Again, the results confirm a prominent role for income in estimating COVID-19 death rates.

Class within Race

The relative power of income as the top risk factor should come as no surprise given that lower income people most often must work away from home in order to survive, often in "essential" employment with a higher risk of virus exposure. Another reason may be connected to the enormous wealth and class disparities within racial, ethnic, and age categories. Not only has systematic racism over the generations disproportionately congregated black and brown working people in the lowest wage jobs, but also systematic runaway inequality in the last 40 years has created enormous wealth extremes between the rich and everyone else within all populations, according to data compiled by Matt Bruenig at the People's Policy Project:

These studies also point out that while the vast majority of our nation's wealth is owned by wealthy whites, "The bottom half of society, which together own just 1.5 percent of the wealth, is thoroughly multiracial with whites making up a slim majority."

While overall the white/black wealth gap on average is almost 7 to 1, there is no racial gap for the bottom 20% of the population--both black and white in the lowest quintile have no wealth at all, according to a report from the Brookings Institution.

This reinforces Dr. Olden's primary political concern: How do we build a coalition of common interest powerful enough to create a healthier society that dramatically reduces poverty? Our COVID-19 data suggests that one focus should be on building solidarity among the vast majority of us who must struggle to make ends meet. It would be worthwhile to do what Dr. Olden has done all his life--build class solidarity while also fighting against racial discrimination in all its forms.

Notes:

* The independent variables used in all five multiple regressions have p scores below .01%, and each variable has a low VIF score reducing the likelihood of multicolinearity. The r squared scores are as follows: NYC deaths 27%; NYC tests, 56%; Chicago deaths, 20%; and Los Angeles deaths, 21%. The number of observations are: NYC, 2,052; Chicago, 4,405; and Los Angeles, 2,272.

** Peter Kreutzer provided extensive research assistance, while Michael Parkin, Professor of Politics, Oberlin College, graciously answered all our questions concerning the regressions. Any statistical errors are of our making, not Professor Parkin's.

Les Leopold is the executive director of the Labor Institute and author of the new book, “Wall Street’s War on Workers: How Mass Layoffs and Greed Are Destroying the Working Class and What to Do About It." (2024). Read more of his work on his substack here.

Dr. Kenneth Olden, former Director of the Howard University Cancer Center (1985-1991), Director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (1991-2005), founding Dean of School of Public Health, City University of New York (2008-2012), and an African-American who grew up dirt poor in Parrotsville, Tennessee, has a message for us.

" Economic inequality is the key to understanding this country's public health problems and the COVID-19 crisis in particular," he told me in an interview earlier this month. "The poorer you are the more your health is at risk. Focusing on the class dimension also helps us build coalitions among lower income people of all colors and ethnicities."

Do the facts back up Dr. Olden's claim about COVID-19?

The answers do not come easily because in the U.S. official COVID-19 illness data--which you can see here--is collected without reference to occupation or income. As a result, media accounts tend to conflate being poor with being African-American or Hispanic.

To gain a more accurate approximation, we use statistical measures of neighborhoods (census tracts) to estimate the independent impacts of race, class, age, housing conditions, and immigration status on who is likely to die from the virus. At the Labor Institute, we have compiled and tested four data sets encompassing positive test and death rates in New York City, and deaths rates in Chicago and Los Angeles. While our results are only statistical estimates due to the lack of direct income/occupational data for each COVID-19 fatality, the findings strongly suggest that Dr. Olden is correct: Income has an enormous impact on who gets sick and who dies.

New York City Revisited

Our initial New York City report, "COVID's Class War" (July 28, 2020) shows that neighborhood median income has the strongest correlation with COVID-19 death rates per zip code. Since then, NYC has released more data for a total of 18,967 deaths by zip code as of August 21. Please note, the average NYC census tract neighborhood in our data base is 41.9% white, 27.3% Hispanic (19.1% born in Latin America), 25.7% Black, 14.3% Asian, 14.3% aged 65 and older, and 1.3% of households with 1.5 or more people per room.

We reran our regression model on this new data, and again the results show that those who live in a neighborhood that is about 1/3 poorer (one standard deviation) than the average New York City neighborhood would face the highest risk of dying from COVID-19, followed closely by age and being born in Latin America (a strong though certainly imperfect proxy for working-class immigrants, including undocumented residents.) Because these results are independent of each other, this data also suggests that the combination of these factors--like being a lower income, elderly immigrant, living in crowded housing--would greatly increase the risk.*

This updated NYC database for the first time also has the percentages of positive COVID-19 deaths per zip code covering more than 1.5 million tests. Our multiple regression reveals** that neighborhoods with about one-third more residents who were born in Latin America faced the most risk with 13.6 percent more positive test results than the average New York neighborhood. Poorer neighborhoods had a 9.3 percent higher rate than an average income neighborhood. It is not difficult to understand that recent immigrants, especially if undocumented, are far less likely to engage with official public health structures until they have no choice for fear of being deported. At the same time they are ineligible for federal benefits and are far more likely to be out in public, either engaged in work or seeking work.

In addition to the 18,967 COVID-19 deaths in our NYC data base, we ran regressions on our Chicago data set (4,400 deaths), and for Los Angeles (5,689 deaths.) The table below provides a weighted average based on the number of COVID-19 deaths in each of the three cities. Again, the results confirm a prominent role for income in estimating COVID-19 death rates.

Class within Race

The relative power of income as the top risk factor should come as no surprise given that lower income people most often must work away from home in order to survive, often in "essential" employment with a higher risk of virus exposure. Another reason may be connected to the enormous wealth and class disparities within racial, ethnic, and age categories. Not only has systematic racism over the generations disproportionately congregated black and brown working people in the lowest wage jobs, but also systematic runaway inequality in the last 40 years has created enormous wealth extremes between the rich and everyone else within all populations, according to data compiled by Matt Bruenig at the People's Policy Project:

These studies also point out that while the vast majority of our nation's wealth is owned by wealthy whites, "The bottom half of society, which together own just 1.5 percent of the wealth, is thoroughly multiracial with whites making up a slim majority."

While overall the white/black wealth gap on average is almost 7 to 1, there is no racial gap for the bottom 20% of the population--both black and white in the lowest quintile have no wealth at all, according to a report from the Brookings Institution.

This reinforces Dr. Olden's primary political concern: How do we build a coalition of common interest powerful enough to create a healthier society that dramatically reduces poverty? Our COVID-19 data suggests that one focus should be on building solidarity among the vast majority of us who must struggle to make ends meet. It would be worthwhile to do what Dr. Olden has done all his life--build class solidarity while also fighting against racial discrimination in all its forms.

Notes:

* The independent variables used in all five multiple regressions have p scores below .01%, and each variable has a low VIF score reducing the likelihood of multicolinearity. The r squared scores are as follows: NYC deaths 27%; NYC tests, 56%; Chicago deaths, 20%; and Los Angeles deaths, 21%. The number of observations are: NYC, 2,052; Chicago, 4,405; and Los Angeles, 2,272.

** Peter Kreutzer provided extensive research assistance, while Michael Parkin, Professor of Politics, Oberlin College, graciously answered all our questions concerning the regressions. Any statistical errors are of our making, not Professor Parkin's.