SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"Things are slowly improving, but remain at historic levels," writes Shierholz. (Photo: Russ Allison Loar / flickr / cc)

Last week, 2.2 million workers applied for unemployment benefits. This is the 13th week in a row--a full three months--that initial unemployment claims are more than twice the worst week of the Great Recession.

Of the 2.2 million who applied for unemployment benefits last week, 1.4 million applied for regular state unemployment insurance (UI) on a not-seasonally-adjusted basis, and 0.8 million applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). PUA is the federal program for workers who are out of work because of the virus but who are not eligible for regular UI (e.g. the self-employed). At this point, only 44 states, DC, and Puerto Rico are reporting PUA claims.

How is it that we are still seeing large numbers of initial unemployment claims now, when the May jobs report shows we added jobs? The missing piece is hiring. If there are a large number of layoffs, there can still be job growth if there is also a lot of hiring (or rehiring). In today's gradually reopening coronavirus economy, hires (or rehires) are now outpacing job losses, but we are still seeing a huge number of people losing jobs. This means labor market "churn" is vastly greater than in normal times.

Further, some recent unemployment claims may be from people who lost their job in March or April but didn't apply right away (perhaps because they couldn't get through the system).

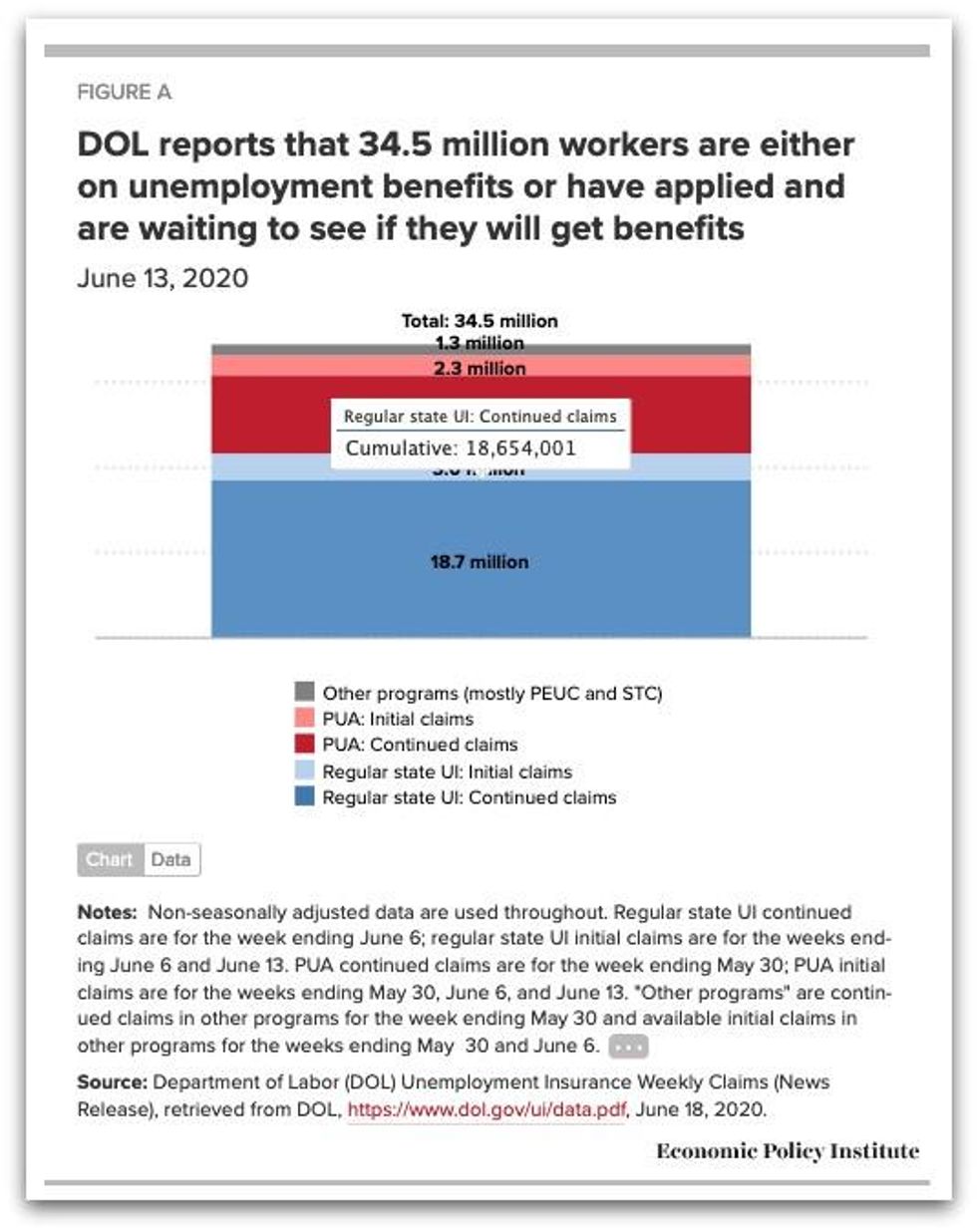

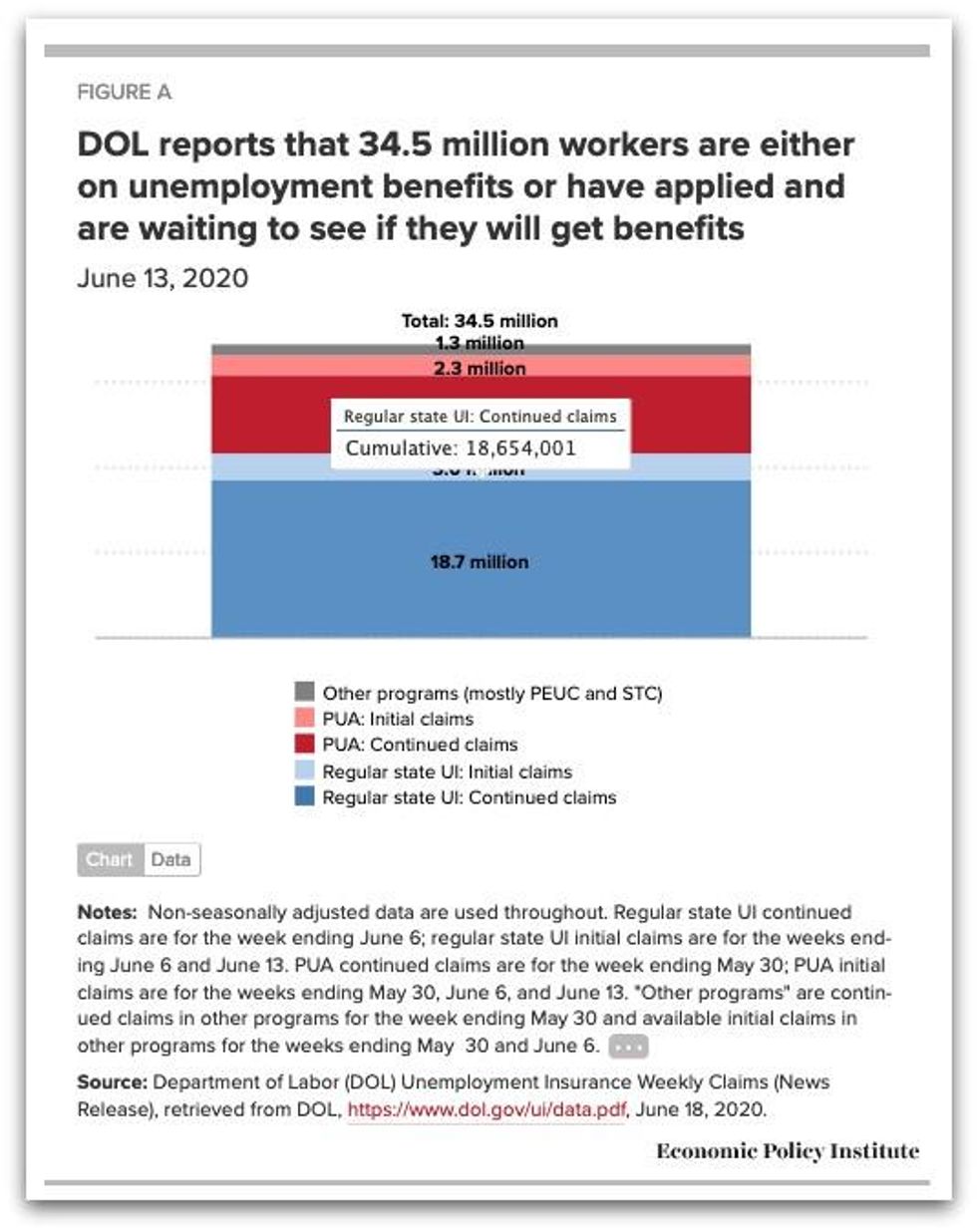

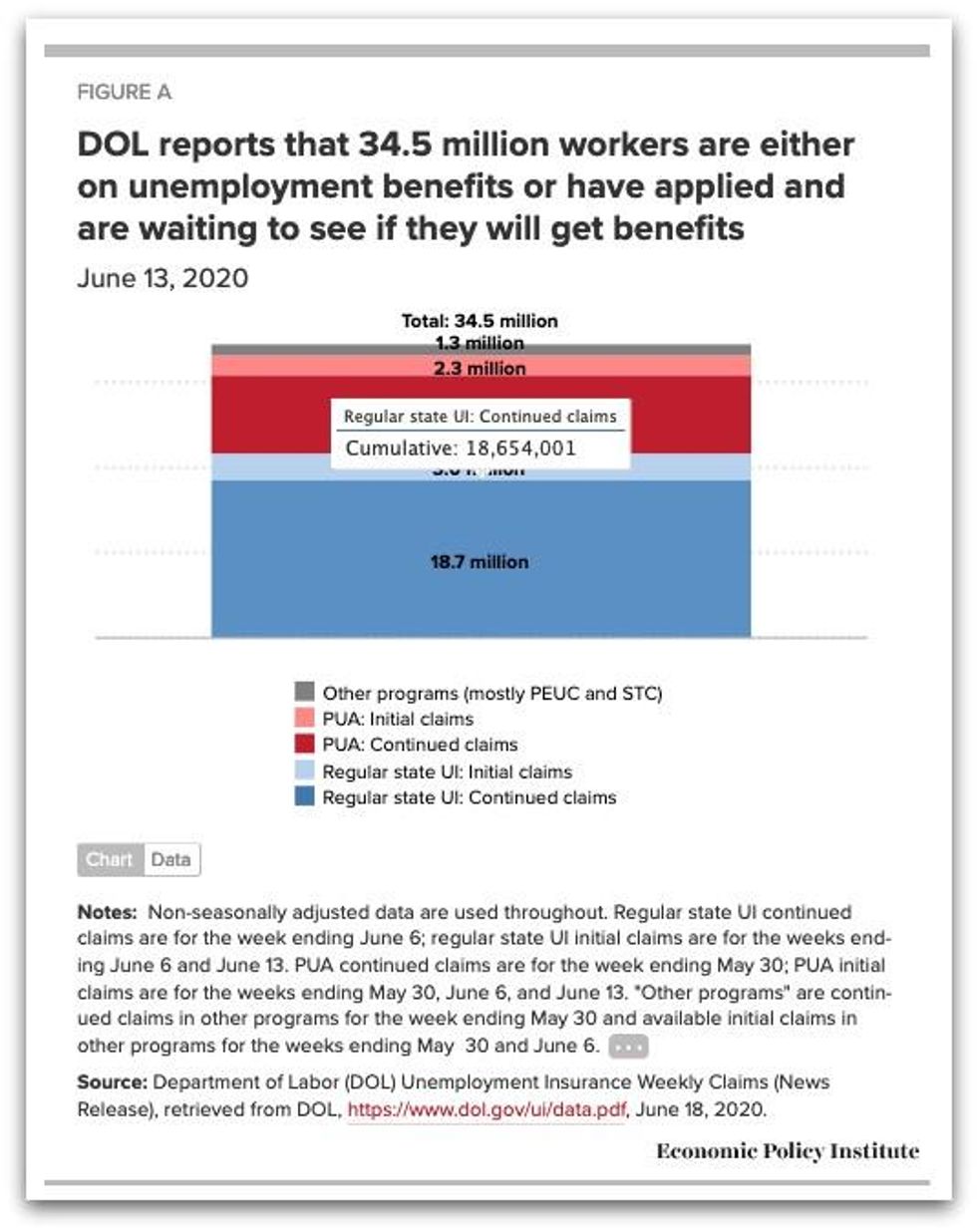

Many commentators are still reporting the cumulative number of initial regular state UI claims over the last 13 weeks as a measure of how many people are out of work because of the virus. I believe we should abandon that approach because it ignores PUA, but overstates things in other ways (for example, some who were laid off and applied for UI in March or April may now be going back to work). Instead, we can calculate the total number of workers who are either on unemployment benefits, or have applied and are waiting to see if they will get benefits, in the following way:

A total of 18.7 million workers had made it through at least the first round of regular state UI processing as of June 6 (these are known as "continued claims" or "insured unemployment"), and 3.0 million had filed initial UI claims on top of that, but had not yet made it through the first round of processing. And, 9.3 million workers had made it through at least the first round of PUA processing by May 30, and 2.3 million had filed initial PUA claims on top of that but had not yet made it through the first round of processing. Even further, by May 30, another 1.3 million workers had made it through at least the first round of processing in one of the other unemployment benefits programs, or had filed initial claims in other programs on top of that. (The largest of the other programs are Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation--which is available to workers who have exhausted their regular state benefits--and Short-Time Compensation, which is an alternative to layoffs where employers reduce work hours rather than laying off workers, and workers get partial benefits.) Altogether, that's 34.5 million workers who are either on unemployment benefits or who have applied very recently and are waiting to see if they will get benefits. That is more than one in five U.S. workers.

It's important to note that of the 34.5 million workers "on" unemployment benefits, a third are on PUA. This is a sobering reminder of how enormous the gaps are in our regular state unemployment insurance programs and how important it is that Congress established the PUA.

Things are slowly improving, but remain at historic levels. Data on continuing claims in all programs are available over time, through May 30. Total continuing claims averaged 1.7 million per week in the year prior to the virus. They rose sharply starting in mid-March, and peaked during the week ending May 9, at 31.0 million. By May 30, they had come down slightly, to 29.2 million, still more than 27 million higher than the pre-virus period.

All in all, today's UI data highlight the deep recession we are now in. It's important to remember that this recession is going to exacerbate existing racial inequalities by causing greater job loss in Black and Hispanic households than in white households.

Policymakers need to act decisively to fight this recession and set our economy up for a strong recovery, which will not happen without substantial additional fiscal aid. For example, without massive federal aid to state and local governments, 5.3 million workers in the public and private sector will likely lose their jobs by the end of 2021. Further, the across-the-board $600 increase in weekly unemployment benefits, which was one of the most effective parts of the CARES Act on both humanitarian and economic grounds, should be extended well past its expiration in late July. We also need increased support for safety net programs, including SNAP (or food stamps). And importantly, we can't turn off federal relief too early. Automatic triggers (where provisions phase out as the unemployment rate falls or the employment-to-population ratio rises) would alleviate the very real threat that we turn off federal aid when the economy is still too weak, hamstringing the recovery.

A note on the unemployment benefits data: claims for UI and PUA should be completely non-overlapping because that is how the Department of Labor has directed state agencies to report them. However, some states may be misreporting claims so there may be some double-counting. Also, I focus on the not-seasonally-adjusted numbers for regular state UI claims because the way DOL does seasonal adjustments of unemployment insurance claims data is distortionary at a time like this. Claims from all other programs, including PUA, are only available on an unadjusted basis.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Last week, 2.2 million workers applied for unemployment benefits. This is the 13th week in a row--a full three months--that initial unemployment claims are more than twice the worst week of the Great Recession.

Of the 2.2 million who applied for unemployment benefits last week, 1.4 million applied for regular state unemployment insurance (UI) on a not-seasonally-adjusted basis, and 0.8 million applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). PUA is the federal program for workers who are out of work because of the virus but who are not eligible for regular UI (e.g. the self-employed). At this point, only 44 states, DC, and Puerto Rico are reporting PUA claims.

How is it that we are still seeing large numbers of initial unemployment claims now, when the May jobs report shows we added jobs? The missing piece is hiring. If there are a large number of layoffs, there can still be job growth if there is also a lot of hiring (or rehiring). In today's gradually reopening coronavirus economy, hires (or rehires) are now outpacing job losses, but we are still seeing a huge number of people losing jobs. This means labor market "churn" is vastly greater than in normal times.

Further, some recent unemployment claims may be from people who lost their job in March or April but didn't apply right away (perhaps because they couldn't get through the system).

Many commentators are still reporting the cumulative number of initial regular state UI claims over the last 13 weeks as a measure of how many people are out of work because of the virus. I believe we should abandon that approach because it ignores PUA, but overstates things in other ways (for example, some who were laid off and applied for UI in March or April may now be going back to work). Instead, we can calculate the total number of workers who are either on unemployment benefits, or have applied and are waiting to see if they will get benefits, in the following way:

A total of 18.7 million workers had made it through at least the first round of regular state UI processing as of June 6 (these are known as "continued claims" or "insured unemployment"), and 3.0 million had filed initial UI claims on top of that, but had not yet made it through the first round of processing. And, 9.3 million workers had made it through at least the first round of PUA processing by May 30, and 2.3 million had filed initial PUA claims on top of that but had not yet made it through the first round of processing. Even further, by May 30, another 1.3 million workers had made it through at least the first round of processing in one of the other unemployment benefits programs, or had filed initial claims in other programs on top of that. (The largest of the other programs are Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation--which is available to workers who have exhausted their regular state benefits--and Short-Time Compensation, which is an alternative to layoffs where employers reduce work hours rather than laying off workers, and workers get partial benefits.) Altogether, that's 34.5 million workers who are either on unemployment benefits or who have applied very recently and are waiting to see if they will get benefits. That is more than one in five U.S. workers.

It's important to note that of the 34.5 million workers "on" unemployment benefits, a third are on PUA. This is a sobering reminder of how enormous the gaps are in our regular state unemployment insurance programs and how important it is that Congress established the PUA.

Things are slowly improving, but remain at historic levels. Data on continuing claims in all programs are available over time, through May 30. Total continuing claims averaged 1.7 million per week in the year prior to the virus. They rose sharply starting in mid-March, and peaked during the week ending May 9, at 31.0 million. By May 30, they had come down slightly, to 29.2 million, still more than 27 million higher than the pre-virus period.

All in all, today's UI data highlight the deep recession we are now in. It's important to remember that this recession is going to exacerbate existing racial inequalities by causing greater job loss in Black and Hispanic households than in white households.

Policymakers need to act decisively to fight this recession and set our economy up for a strong recovery, which will not happen without substantial additional fiscal aid. For example, without massive federal aid to state and local governments, 5.3 million workers in the public and private sector will likely lose their jobs by the end of 2021. Further, the across-the-board $600 increase in weekly unemployment benefits, which was one of the most effective parts of the CARES Act on both humanitarian and economic grounds, should be extended well past its expiration in late July. We also need increased support for safety net programs, including SNAP (or food stamps). And importantly, we can't turn off federal relief too early. Automatic triggers (where provisions phase out as the unemployment rate falls or the employment-to-population ratio rises) would alleviate the very real threat that we turn off federal aid when the economy is still too weak, hamstringing the recovery.

A note on the unemployment benefits data: claims for UI and PUA should be completely non-overlapping because that is how the Department of Labor has directed state agencies to report them. However, some states may be misreporting claims so there may be some double-counting. Also, I focus on the not-seasonally-adjusted numbers for regular state UI claims because the way DOL does seasonal adjustments of unemployment insurance claims data is distortionary at a time like this. Claims from all other programs, including PUA, are only available on an unadjusted basis.

Last week, 2.2 million workers applied for unemployment benefits. This is the 13th week in a row--a full three months--that initial unemployment claims are more than twice the worst week of the Great Recession.

Of the 2.2 million who applied for unemployment benefits last week, 1.4 million applied for regular state unemployment insurance (UI) on a not-seasonally-adjusted basis, and 0.8 million applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). PUA is the federal program for workers who are out of work because of the virus but who are not eligible for regular UI (e.g. the self-employed). At this point, only 44 states, DC, and Puerto Rico are reporting PUA claims.

How is it that we are still seeing large numbers of initial unemployment claims now, when the May jobs report shows we added jobs? The missing piece is hiring. If there are a large number of layoffs, there can still be job growth if there is also a lot of hiring (or rehiring). In today's gradually reopening coronavirus economy, hires (or rehires) are now outpacing job losses, but we are still seeing a huge number of people losing jobs. This means labor market "churn" is vastly greater than in normal times.

Further, some recent unemployment claims may be from people who lost their job in March or April but didn't apply right away (perhaps because they couldn't get through the system).

Many commentators are still reporting the cumulative number of initial regular state UI claims over the last 13 weeks as a measure of how many people are out of work because of the virus. I believe we should abandon that approach because it ignores PUA, but overstates things in other ways (for example, some who were laid off and applied for UI in March or April may now be going back to work). Instead, we can calculate the total number of workers who are either on unemployment benefits, or have applied and are waiting to see if they will get benefits, in the following way:

A total of 18.7 million workers had made it through at least the first round of regular state UI processing as of June 6 (these are known as "continued claims" or "insured unemployment"), and 3.0 million had filed initial UI claims on top of that, but had not yet made it through the first round of processing. And, 9.3 million workers had made it through at least the first round of PUA processing by May 30, and 2.3 million had filed initial PUA claims on top of that but had not yet made it through the first round of processing. Even further, by May 30, another 1.3 million workers had made it through at least the first round of processing in one of the other unemployment benefits programs, or had filed initial claims in other programs on top of that. (The largest of the other programs are Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation--which is available to workers who have exhausted their regular state benefits--and Short-Time Compensation, which is an alternative to layoffs where employers reduce work hours rather than laying off workers, and workers get partial benefits.) Altogether, that's 34.5 million workers who are either on unemployment benefits or who have applied very recently and are waiting to see if they will get benefits. That is more than one in five U.S. workers.

It's important to note that of the 34.5 million workers "on" unemployment benefits, a third are on PUA. This is a sobering reminder of how enormous the gaps are in our regular state unemployment insurance programs and how important it is that Congress established the PUA.

Things are slowly improving, but remain at historic levels. Data on continuing claims in all programs are available over time, through May 30. Total continuing claims averaged 1.7 million per week in the year prior to the virus. They rose sharply starting in mid-March, and peaked during the week ending May 9, at 31.0 million. By May 30, they had come down slightly, to 29.2 million, still more than 27 million higher than the pre-virus period.

All in all, today's UI data highlight the deep recession we are now in. It's important to remember that this recession is going to exacerbate existing racial inequalities by causing greater job loss in Black and Hispanic households than in white households.

Policymakers need to act decisively to fight this recession and set our economy up for a strong recovery, which will not happen without substantial additional fiscal aid. For example, without massive federal aid to state and local governments, 5.3 million workers in the public and private sector will likely lose their jobs by the end of 2021. Further, the across-the-board $600 increase in weekly unemployment benefits, which was one of the most effective parts of the CARES Act on both humanitarian and economic grounds, should be extended well past its expiration in late July. We also need increased support for safety net programs, including SNAP (or food stamps). And importantly, we can't turn off federal relief too early. Automatic triggers (where provisions phase out as the unemployment rate falls or the employment-to-population ratio rises) would alleviate the very real threat that we turn off federal aid when the economy is still too weak, hamstringing the recovery.

A note on the unemployment benefits data: claims for UI and PUA should be completely non-overlapping because that is how the Department of Labor has directed state agencies to report them. However, some states may be misreporting claims so there may be some double-counting. Also, I focus on the not-seasonally-adjusted numbers for regular state UI claims because the way DOL does seasonal adjustments of unemployment insurance claims data is distortionary at a time like this. Claims from all other programs, including PUA, are only available on an unadjusted basis.