SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

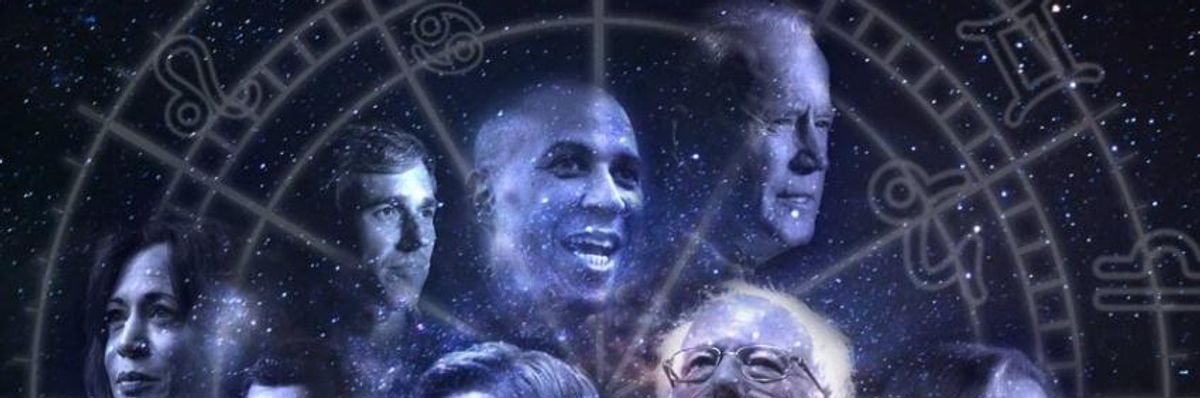

Candidates up and down the ballot routinely disprove the notion that only white or male or centrist candidates can win a competitive election. (Photo illustration by Matt Whitt/Photos via Getty Images)

When Ayanna Pressley was first elected to the Boston City Council in 2009, she wasn't the image of an "electable" candidate. In the 100 years of the Boston City Council, there had never been a woman of color.

Fast forward eight years, and "electability" in Boston looked pretty different. In 2017, six of the 13 councilors elected were women of color, and the Council is more willing to defy the mayor and push for progressive policies. It's possible that, come 2020, the Council will be majority female and majority people of color.

Electability is no more a science than astrology. Indeed, it is often little more than calcified prejudice.

Pressley won't be there, though. She's now in Congress.

In 2018, when Pressley ran against 20-year incumbent Rep. Michael Capuano in Massachusetts's 7th District, insiders didn't think she had much of a chance. An informal poll of more than 50 local political insiders by WGBH found 81% expected a Capuano victory. Indeed, polling a month before the election showed that she was largely unknown to voters, lagging by 13 points. But Pressley won by 17.

These insiders were also proven wrong in Boston's race for district attorney. They deemed the white, Irish, male, conservative candidate the frontrunner, citing the city's demographics and a belief that voters wouldn't take to criminal justice reform. Instead, Rachael Rollins, a woman of color who opposes cash bail, won big.

If you live in Boston (as I do), it's clear how Pressley and Rollins managed their upset victories: They both had aggressive ground games. Pressley volunteers, persuaded by the passion and urgency of Pressley's "change can't wait" message, turned out thousands of infrequent voters. Rollins won after activist groups coalesced behind her and pounded the pavement to explain why the district attorney, an office few pay attention to, was so important.

Boston was not the only place to see the established wisdom of "electability" upended in 2018. Voters in Orange County, Calif., known as a Republican stronghold, not only elected Democrats in all seven House districts, but elected Democrats like Katie Porter and Mike Levin, who support Medicare for All and other progressive priorities. Porter and Levin defied the conventional wisdom that running to the center is the way to win swing seats, and they won because people--many organized through dozens of new grassroots organizations-- were enthusiastic enough to work to get them elected.

Even candidates who lose can change what "electability" looks like. Stacey Abrams may not be Georgia's governor (we can thank voter suppression for that), but she received more votes than any Democrat ever running statewide in Georgia, and a higher percentage of the vote (48.8%) than any Democratic gubernatorial candidate since 1998. In 2014, Georgia Democrats ran the centrist grandson of Jimmy Carter for governor; he got 44.9%. Abrams, a Black woman with a progressive platform, outperformed him by amassing thousands of volunteers to knock doors and make calls.

As we go into 2020, it is important to remember so-called electability is no more a science than astrology. Indeed, it is often little more than calcified prejudice. Candidates up and down the ballot routinely disprove the notion that only white or male or centrist candidates can win a competitive election. And they do so by inspiring everyday people to put blood, sweat and tears (and money) into their campaigns.

So, when weighing which presidential candidate to back in the Democratic primary, voters should dispense with a definition of "electability" that relies on gaming out what other voters will do. The test should be whether you are willing to work to get that candidate elected--and can inspire others to join you.

The best advice on electability I have ever heard comes not from any TV pundit or elite columnist, but from a bottle cap still sitting on my bureau: Good things come to those who hustle.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

When Ayanna Pressley was first elected to the Boston City Council in 2009, she wasn't the image of an "electable" candidate. In the 100 years of the Boston City Council, there had never been a woman of color.

Fast forward eight years, and "electability" in Boston looked pretty different. In 2017, six of the 13 councilors elected were women of color, and the Council is more willing to defy the mayor and push for progressive policies. It's possible that, come 2020, the Council will be majority female and majority people of color.

Electability is no more a science than astrology. Indeed, it is often little more than calcified prejudice.

Pressley won't be there, though. She's now in Congress.

In 2018, when Pressley ran against 20-year incumbent Rep. Michael Capuano in Massachusetts's 7th District, insiders didn't think she had much of a chance. An informal poll of more than 50 local political insiders by WGBH found 81% expected a Capuano victory. Indeed, polling a month before the election showed that she was largely unknown to voters, lagging by 13 points. But Pressley won by 17.

These insiders were also proven wrong in Boston's race for district attorney. They deemed the white, Irish, male, conservative candidate the frontrunner, citing the city's demographics and a belief that voters wouldn't take to criminal justice reform. Instead, Rachael Rollins, a woman of color who opposes cash bail, won big.

If you live in Boston (as I do), it's clear how Pressley and Rollins managed their upset victories: They both had aggressive ground games. Pressley volunteers, persuaded by the passion and urgency of Pressley's "change can't wait" message, turned out thousands of infrequent voters. Rollins won after activist groups coalesced behind her and pounded the pavement to explain why the district attorney, an office few pay attention to, was so important.

Boston was not the only place to see the established wisdom of "electability" upended in 2018. Voters in Orange County, Calif., known as a Republican stronghold, not only elected Democrats in all seven House districts, but elected Democrats like Katie Porter and Mike Levin, who support Medicare for All and other progressive priorities. Porter and Levin defied the conventional wisdom that running to the center is the way to win swing seats, and they won because people--many organized through dozens of new grassroots organizations-- were enthusiastic enough to work to get them elected.

Even candidates who lose can change what "electability" looks like. Stacey Abrams may not be Georgia's governor (we can thank voter suppression for that), but she received more votes than any Democrat ever running statewide in Georgia, and a higher percentage of the vote (48.8%) than any Democratic gubernatorial candidate since 1998. In 2014, Georgia Democrats ran the centrist grandson of Jimmy Carter for governor; he got 44.9%. Abrams, a Black woman with a progressive platform, outperformed him by amassing thousands of volunteers to knock doors and make calls.

As we go into 2020, it is important to remember so-called electability is no more a science than astrology. Indeed, it is often little more than calcified prejudice. Candidates up and down the ballot routinely disprove the notion that only white or male or centrist candidates can win a competitive election. And they do so by inspiring everyday people to put blood, sweat and tears (and money) into their campaigns.

So, when weighing which presidential candidate to back in the Democratic primary, voters should dispense with a definition of "electability" that relies on gaming out what other voters will do. The test should be whether you are willing to work to get that candidate elected--and can inspire others to join you.

The best advice on electability I have ever heard comes not from any TV pundit or elite columnist, but from a bottle cap still sitting on my bureau: Good things come to those who hustle.

When Ayanna Pressley was first elected to the Boston City Council in 2009, she wasn't the image of an "electable" candidate. In the 100 years of the Boston City Council, there had never been a woman of color.

Fast forward eight years, and "electability" in Boston looked pretty different. In 2017, six of the 13 councilors elected were women of color, and the Council is more willing to defy the mayor and push for progressive policies. It's possible that, come 2020, the Council will be majority female and majority people of color.

Electability is no more a science than astrology. Indeed, it is often little more than calcified prejudice.

Pressley won't be there, though. She's now in Congress.

In 2018, when Pressley ran against 20-year incumbent Rep. Michael Capuano in Massachusetts's 7th District, insiders didn't think she had much of a chance. An informal poll of more than 50 local political insiders by WGBH found 81% expected a Capuano victory. Indeed, polling a month before the election showed that she was largely unknown to voters, lagging by 13 points. But Pressley won by 17.

These insiders were also proven wrong in Boston's race for district attorney. They deemed the white, Irish, male, conservative candidate the frontrunner, citing the city's demographics and a belief that voters wouldn't take to criminal justice reform. Instead, Rachael Rollins, a woman of color who opposes cash bail, won big.

If you live in Boston (as I do), it's clear how Pressley and Rollins managed their upset victories: They both had aggressive ground games. Pressley volunteers, persuaded by the passion and urgency of Pressley's "change can't wait" message, turned out thousands of infrequent voters. Rollins won after activist groups coalesced behind her and pounded the pavement to explain why the district attorney, an office few pay attention to, was so important.

Boston was not the only place to see the established wisdom of "electability" upended in 2018. Voters in Orange County, Calif., known as a Republican stronghold, not only elected Democrats in all seven House districts, but elected Democrats like Katie Porter and Mike Levin, who support Medicare for All and other progressive priorities. Porter and Levin defied the conventional wisdom that running to the center is the way to win swing seats, and they won because people--many organized through dozens of new grassroots organizations-- were enthusiastic enough to work to get them elected.

Even candidates who lose can change what "electability" looks like. Stacey Abrams may not be Georgia's governor (we can thank voter suppression for that), but she received more votes than any Democrat ever running statewide in Georgia, and a higher percentage of the vote (48.8%) than any Democratic gubernatorial candidate since 1998. In 2014, Georgia Democrats ran the centrist grandson of Jimmy Carter for governor; he got 44.9%. Abrams, a Black woman with a progressive platform, outperformed him by amassing thousands of volunteers to knock doors and make calls.

As we go into 2020, it is important to remember so-called electability is no more a science than astrology. Indeed, it is often little more than calcified prejudice. Candidates up and down the ballot routinely disprove the notion that only white or male or centrist candidates can win a competitive election. And they do so by inspiring everyday people to put blood, sweat and tears (and money) into their campaigns.

So, when weighing which presidential candidate to back in the Democratic primary, voters should dispense with a definition of "electability" that relies on gaming out what other voters will do. The test should be whether you are willing to work to get that candidate elected--and can inspire others to join you.

The best advice on electability I have ever heard comes not from any TV pundit or elite columnist, but from a bottle cap still sitting on my bureau: Good things come to those who hustle.