Burlington Vermont is cold in late November. Huge mounds of recently cleared snow attest to the coming of winter, which in this part of the world, just below the Canadian border and far from the warming influence of the oceans, is long, dark and absolutely freezing.

The shops of Church Street are doing a brisk business in quilted jackets, boots and woolly hats. With its open log fires, law-abiding citizens and reusable coffee mugs, there's a touch of a little Denmark in North America about this place. That is until you see the row upon row of F-16 fighter jets in the airport terminal.

This is definitely America; but it's not the America we have come to expect in the era of Trump. Vermont is a tolerant, wealthy, almost Trudeauesque corner of the US. It was the first state to abolish slavery, is home to the hippy ice cream moguls Ben and Jerry, and has returned Bernie Sanders to the Senate for the past two decades.

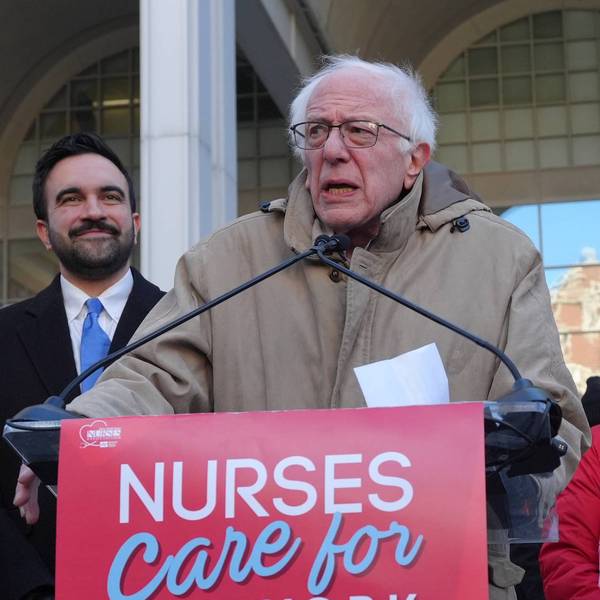

"Watching Sanders this morning, cajoling his troops, emoting his followers and leading them again, it is clear that what underlies his movement and gives him energy is the cause. The objective to give more and more people access to some of the enormous wealth of this extraordinary country."

Last year, Sanders came to the Dalkey Book Festival (of which I am co-curator) and lit up a capacity audience at the Bord Gais Energy Theatre with his lively rhetoric, boundless energy and relentless optimism.

This week I am in Vermont to chair a discussion with him at what could be something of a dry run for his potential bid for the 2020 US presidential election. The Sanders Institute has organised a two-day think-in of liberal Democrats from across the US with a few foreign interlopers thrown in, to tease out the issues upon which a progressive presidential candidate might run.

An array of political thinkers, activists and other household names have gathered to create not just a political party but something more akin to a movement that aims to reposition the Democrats away from the Clinton axis of Wall Street, Hollywood and Silicon Valley and in favour of the working, blue-collar Americans that built the Democratic Party in the first place.

Sanders wants to speak to the people who voted for Trump - the Deplorables - as well as those who voted for Hillary Clinton, winning her the popular vote.

Sanders's people are as much the disenfranchised white swing voters who vouched for Trump, as the traditional social liberals who backed him in Vermont from the start.

He is trying to create a broad coalition against Trump. Endeavouring to do this from the left is much trickier than building something similar from the right; the left's ability to foster schisms, dissent and divorce is legendary. While movements on the right start out looking for converts, movements on the left start out looking for traitors.

If he wants to succeed, Sanders has to forge an alliance among his own side before looking to persuade others.

The 'infinite game'

In this regard, it was interesting to listen to the author Simon Sinek, whose Ted Talk is the third most watched. Sinek spoke about how to create an ongoing political movement rather than organisation focused on one event - let's say a referendum or a general election.

He touched on issues I referred to in this column last week surrounding the constant commercial churn in the economy, which economists call "creative destruction", whereby companies are constantly outsmarting each other, introducing new innovations and jostling for position. Sinek refers to the relentless churn of business and the economy as the "infinite game", where there is no end.

The endless game of politics is similar. There is no point where a politician can declare victory, because there is no referee who will blow a whistle and say that the game is over. Even if you win an election, you are on to the next campaign. This is why building a movement of shared values, on top of an election crusade of specific objectives, is critical to changing the political culture of a country.

The difference between the infinite game and the finite game is enormous. The finite game is one where you have rules, time frames and specific attainable goals. This produces winners and deploys the language we hear used all the time in business, economics and politics.

Such a score card is great for soccer or rugby, but does it hold for society? Are there always clear winners? Is there a target that once achieved, we can declare the game is over and we all go home? Not really.

The cause

The example of the Vietnam war was invoked to explain the difference between the infinite and the finite mindset. In 1968, the North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive, a mass surprise uprising against the Americans in more than 200 locations, organised for Tet, the Vietnamese new year, traditionally a day of peace.

The North Vietnamese believed that this would swing the stalemate but it didn't. The Americans fought vigorously, pushing the Viet Cong back at every battle, losing far fewer men and territory, exhausting their enemy. Yet despite winning on the field, eventually the Americans lost the war.

The reason may have been that the Americans had a finite mindset, which had goals like defeating communism in Vietnam, installing a new government, spending as much money as was available and getting out. The Vietnamese in contrast had an infinite mindset which was to fight for their lives; there was no partial victory for them, no pullout, no end.

All there was for the Vietnamese was the infinite game, one that had no referee blowing time, no election result to try to aim for, no independent arbiter of success. They simply had a just cause - the most powerful motive of all.

Building a movement is similar. It goes on and on and on, but to succeed it must have a cause.

Watching Sanders this morning, cajoling his troops, emoting his followers and leading them again, it is clear that what underlies his movement and gives him energy is the cause. The objective to give more and more people access to some of the enormous wealth of this extraordinary country.

The way he was talking, you'd be mad to rule out another presidential bid in 2020. The United States will be far the richer if he does throw his hat in the ring again.