SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"This is not the first time US media, or the New York Times in particular, have erased US responsibility Libya's travails." (Photo: Screenshot)

New York Times Cairo bureau chief Declan Walsh went to Benghazi, Libya, which is in ruins, to find out how it got that way.

"When I went to Benghazi, I was guided by one main question: How did the city come to this?" he declares in his multimedia presentation, which combines text, audio, video and large-format photography. One thing that's not conveyed via any medium, though: Seven years ago, the United States and its allies used military force to overthrow Libya's government. The country has been in almost continual civil war since then, which you would think would be crucial in explaining "how the city came to that." But apparently you don't think like a New York Times bureau chief.

The thing is, when President Barack Obama--egged on by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton--called for an attack on Libya, the justification they offered was that Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi would otherwise destroy Benghazi. So the fact that military intervention actually turned out to lead to the destruction of Benghazi seems like something you might want to tell Times readers, or Times consumers of multimedia, anyway.

But Walsh, despite his stated objective, seemed to go out of his way to avoid talking about how Libya has come to be a place where major cities are turned to rubble. Here's how the piece opens:

When a "mob attack" killed the US ambassador in 2012--"that's when the real fight began." In other words, the "real fight" didn't begin a year earlier, when NATO added its overwhelming military might to a rebel uprising against Gadhafi.

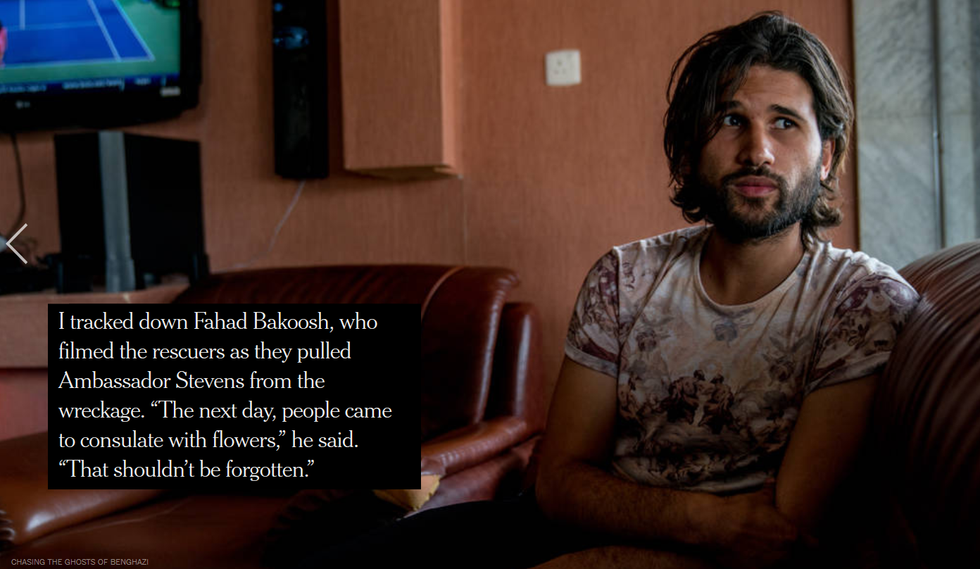

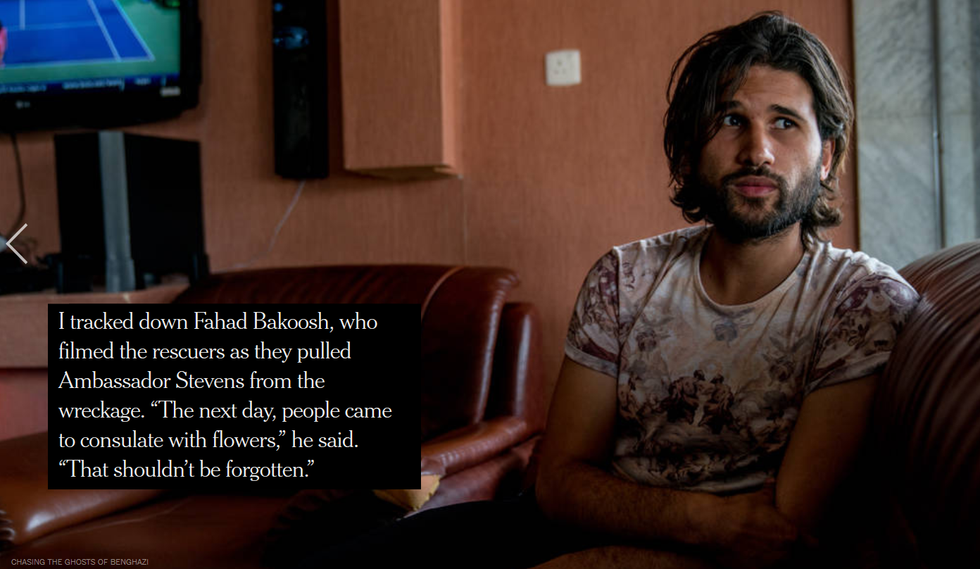

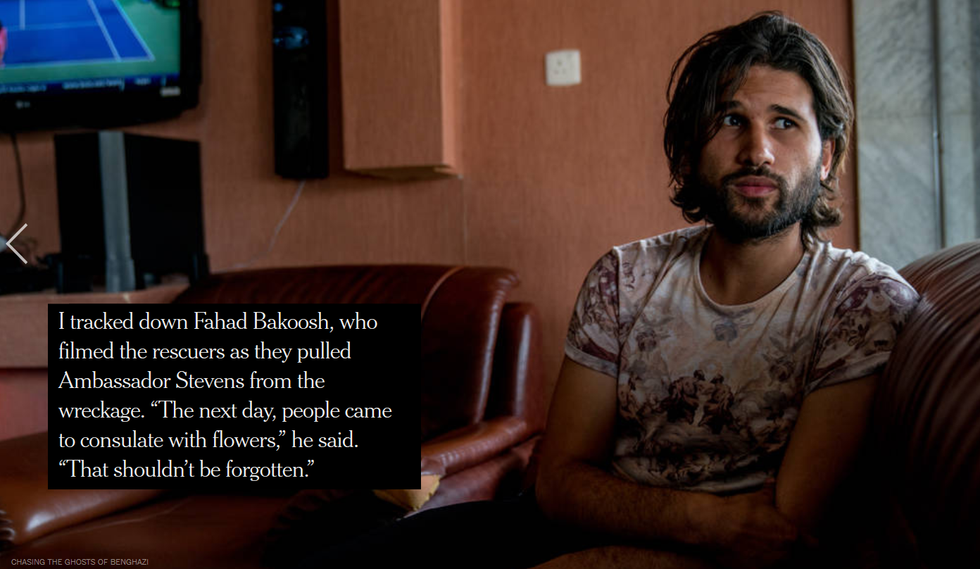

It's almost as if Walsh thinks that his audience, conditioned as they are by corporate media's indulgence of the Republican Party's absurd obsession with whether Clinton accurately characterized the motivations of the militants who killed Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens, can only use that frame of reference to understand Benghazi. So we get assurances that not every Benghazi resident hated the United States--some brought flowers!--but no explanation for why Libyan resentment of the United States might be justified:

"That shouldn't be forgotten"--unlike the US destroying the government of Libya and leaving the nation to be fought over by warlords.

It's not like Walsh hasn't heard of history--he notes the historical trivia that Benito Mussolini once gave a speech from a Benghazi balcony. There's room in the piece to mention Mussolini, but Obama and Clinton? They don't come up.

This is not the first time US media, or the New York Times in particular, have erased US responsibility Libya's travails. Ben Norton wrote a piece for FAIR (11/28/17) about coverage of the return of slave markets to Libya; the Times did better than most outlets by acknowledging that the resurgence of slavery was connected to the chaos following the downfall of Gadhafi--but couldn't bring itself to remind readers that their own government helped bring about that downfall.

But when a journalist sets out--"guided by one main question"--to understand the roots of devastating violence in a particular city, and fails so utterly to take the overwhelming role of Washington intervention into account.... Well, I've been doing this a long time, and I have to say I was startled by the complete erasure of quite recent, utterly relevant events.

You're left wondering what Walsh does intend to offer as an explanation for Benghazi's destruction. Perhaps it's inherent in the Libyan character, as he suggests is illustrated by locals' enthusiasm for doing "doughnuts" in their cars--a sport that reminded Walsh "of so many young Libyans I met--restless after years of war, impatient to go somewhere and yet turning in circles."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

New York Times Cairo bureau chief Declan Walsh went to Benghazi, Libya, which is in ruins, to find out how it got that way.

"When I went to Benghazi, I was guided by one main question: How did the city come to this?" he declares in his multimedia presentation, which combines text, audio, video and large-format photography. One thing that's not conveyed via any medium, though: Seven years ago, the United States and its allies used military force to overthrow Libya's government. The country has been in almost continual civil war since then, which you would think would be crucial in explaining "how the city came to that." But apparently you don't think like a New York Times bureau chief.

The thing is, when President Barack Obama--egged on by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton--called for an attack on Libya, the justification they offered was that Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi would otherwise destroy Benghazi. So the fact that military intervention actually turned out to lead to the destruction of Benghazi seems like something you might want to tell Times readers, or Times consumers of multimedia, anyway.

But Walsh, despite his stated objective, seemed to go out of his way to avoid talking about how Libya has come to be a place where major cities are turned to rubble. Here's how the piece opens:

When a "mob attack" killed the US ambassador in 2012--"that's when the real fight began." In other words, the "real fight" didn't begin a year earlier, when NATO added its overwhelming military might to a rebel uprising against Gadhafi.

It's almost as if Walsh thinks that his audience, conditioned as they are by corporate media's indulgence of the Republican Party's absurd obsession with whether Clinton accurately characterized the motivations of the militants who killed Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens, can only use that frame of reference to understand Benghazi. So we get assurances that not every Benghazi resident hated the United States--some brought flowers!--but no explanation for why Libyan resentment of the United States might be justified:

"That shouldn't be forgotten"--unlike the US destroying the government of Libya and leaving the nation to be fought over by warlords.

It's not like Walsh hasn't heard of history--he notes the historical trivia that Benito Mussolini once gave a speech from a Benghazi balcony. There's room in the piece to mention Mussolini, but Obama and Clinton? They don't come up.

This is not the first time US media, or the New York Times in particular, have erased US responsibility Libya's travails. Ben Norton wrote a piece for FAIR (11/28/17) about coverage of the return of slave markets to Libya; the Times did better than most outlets by acknowledging that the resurgence of slavery was connected to the chaos following the downfall of Gadhafi--but couldn't bring itself to remind readers that their own government helped bring about that downfall.

But when a journalist sets out--"guided by one main question"--to understand the roots of devastating violence in a particular city, and fails so utterly to take the overwhelming role of Washington intervention into account.... Well, I've been doing this a long time, and I have to say I was startled by the complete erasure of quite recent, utterly relevant events.

You're left wondering what Walsh does intend to offer as an explanation for Benghazi's destruction. Perhaps it's inherent in the Libyan character, as he suggests is illustrated by locals' enthusiasm for doing "doughnuts" in their cars--a sport that reminded Walsh "of so many young Libyans I met--restless after years of war, impatient to go somewhere and yet turning in circles."

New York Times Cairo bureau chief Declan Walsh went to Benghazi, Libya, which is in ruins, to find out how it got that way.

"When I went to Benghazi, I was guided by one main question: How did the city come to this?" he declares in his multimedia presentation, which combines text, audio, video and large-format photography. One thing that's not conveyed via any medium, though: Seven years ago, the United States and its allies used military force to overthrow Libya's government. The country has been in almost continual civil war since then, which you would think would be crucial in explaining "how the city came to that." But apparently you don't think like a New York Times bureau chief.

The thing is, when President Barack Obama--egged on by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton--called for an attack on Libya, the justification they offered was that Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi would otherwise destroy Benghazi. So the fact that military intervention actually turned out to lead to the destruction of Benghazi seems like something you might want to tell Times readers, or Times consumers of multimedia, anyway.

But Walsh, despite his stated objective, seemed to go out of his way to avoid talking about how Libya has come to be a place where major cities are turned to rubble. Here's how the piece opens:

When a "mob attack" killed the US ambassador in 2012--"that's when the real fight began." In other words, the "real fight" didn't begin a year earlier, when NATO added its overwhelming military might to a rebel uprising against Gadhafi.

It's almost as if Walsh thinks that his audience, conditioned as they are by corporate media's indulgence of the Republican Party's absurd obsession with whether Clinton accurately characterized the motivations of the militants who killed Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens, can only use that frame of reference to understand Benghazi. So we get assurances that not every Benghazi resident hated the United States--some brought flowers!--but no explanation for why Libyan resentment of the United States might be justified:

"That shouldn't be forgotten"--unlike the US destroying the government of Libya and leaving the nation to be fought over by warlords.

It's not like Walsh hasn't heard of history--he notes the historical trivia that Benito Mussolini once gave a speech from a Benghazi balcony. There's room in the piece to mention Mussolini, but Obama and Clinton? They don't come up.

This is not the first time US media, or the New York Times in particular, have erased US responsibility Libya's travails. Ben Norton wrote a piece for FAIR (11/28/17) about coverage of the return of slave markets to Libya; the Times did better than most outlets by acknowledging that the resurgence of slavery was connected to the chaos following the downfall of Gadhafi--but couldn't bring itself to remind readers that their own government helped bring about that downfall.

But when a journalist sets out--"guided by one main question"--to understand the roots of devastating violence in a particular city, and fails so utterly to take the overwhelming role of Washington intervention into account.... Well, I've been doing this a long time, and I have to say I was startled by the complete erasure of quite recent, utterly relevant events.

You're left wondering what Walsh does intend to offer as an explanation for Benghazi's destruction. Perhaps it's inherent in the Libyan character, as he suggests is illustrated by locals' enthusiasm for doing "doughnuts" in their cars--a sport that reminded Walsh "of so many young Libyans I met--restless after years of war, impatient to go somewhere and yet turning in circles."