With a billionaire real estate tycoon occupying America's highest office, the effects of riches upon the soul are a reasonable concern for all of us little guys. After all, one incredibly wealthy soul currently holds our country in his hands. According to an apocryphal exchange between F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, the only difference between the rich and the rest of us is that they have more money. But is that the only difference?

We didn't used to think so. We used to think that having vast sums of money was bad and in particular bad for you -- that it harmed your character, warping your behavior and corrupting your soul. We thought the rich were different, and different for the worse.

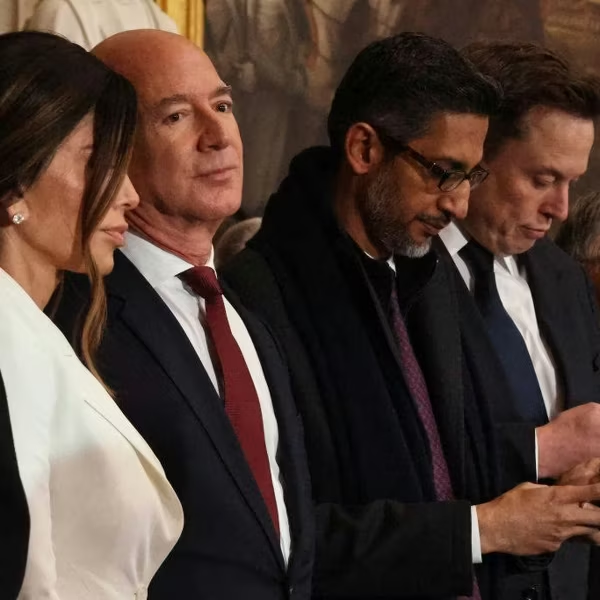

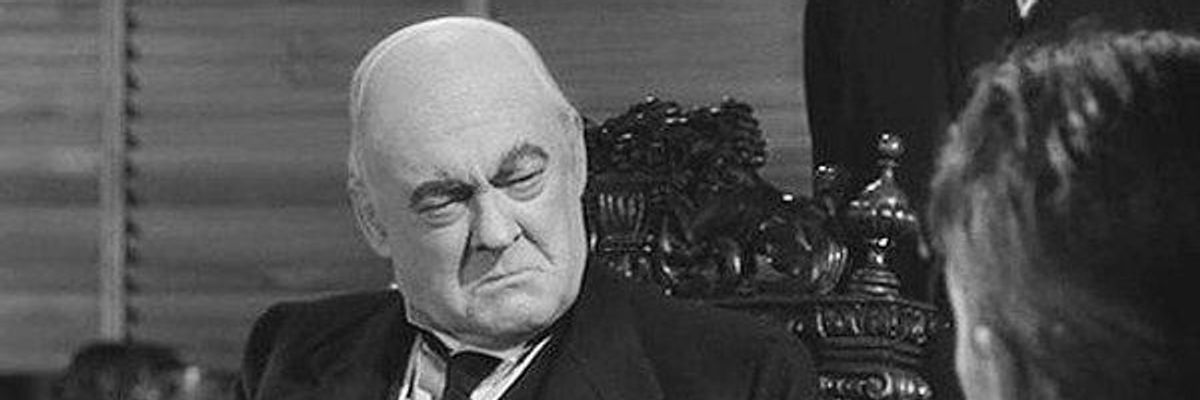

Today, however, we seem less confident of this. We seem to view wealth as simply good or neutral, and chalk up the failures of individual wealthy people to their own personal flaws, not their riches. Those who are rich, we seem to think, are not in any more moral danger than the rest of us. Compare how old movies preached the folk wisdom of wealth's morally calamitous effects to how contemporary movies portray wealth: For example, the villainous Mr. Potter from "It's A Wonderful Life" to the heroic Tony Stark (that is, Iron Man) in the Avengers films.

The idea that wealth is morally perilous has an impressive philosophical and religious pedigree. Ancient Stoic philosophers railed against greed and luxury, and Roman historians such as Tacitus lay many of the empire's struggles at the feet of imperial avarice. Confucius lived an austere life. The Buddha famously left his opulent palace behind. And Jesus didn't exactly go easy on the rich, either -- think camels and needles, for starters.

The point is not necessarily that wealth is intrinsically and everywhere evil, but that it is dangerous -- that it should be eyed with caution and suspicion, and definitely not pursued as an end in itself; that great riches pose great risks to their owners; and that societies are right to stigmatize the storing up of untold wealth. That's why Aristotle, for instance, argued that wealth should be sought only for the sake of living virtuously -- to manage a household, say, or to participate in the life of the polis. Here wealth is useful but not inherently good; indeed, Aristotle specifically warned that the accumulation of wealth for its own sake corrupts virtue instead of enabling it. For Hindus, working hard to earn money is a duty (dharma), but only when done through honest means and used for good ends. The function of money is not to satiate greed but to support oneself and one's family. The Koran, too, warns against hoarding money and enjoins Muslims to disperse it to the needy.

Some contemporary voices join this ancient chorus, perhaps none more enthusiastically than Pope Francis. He's proclaimed that unless wealth is used for the good of society, and above all for the good of the poor, it is an instrument "of corruption and death." And Francis lives what he teaches: Despite access to some of the sweetest real estate imaginable -- the palatial papal apartments are the sort of thing that President Trump's gold-plated extravagance is a parody of -- the pope bunks in a small suite in what is effectively the Vatican's hostel. In his official state visit to Washington, he pulled up to the White House in a Fiat so sensible that a denizen of Northwest D.C. would be almost embarrassed to drive it. When Francis entered the Jesuit order 59 years ago, he took a vow of poverty, and he's kept it.

According to many philosophies and faiths, then, wealth should serve only as a steppingstone to some further good and is always fraught with moral danger. We all used to recognize this; it was a commonplace. And this intuition, shared by various cultures across history, stands on firm empirical ground.

Over the past few years, a pile of studies from the behavioral sciences has appeared, and they all say, more or less, "Being rich is really bad for you." Wealth, it turns out, leads to behavioral and psychological maladies. The rich act and think in misdirected ways.

When it comes to a broad range of vices, the rich outperform everybody else. They are much more likely than the rest of humanity to shoplift and cheat , for example, and they are more apt to be adulterers and to drink a great deal . They are even more likely to take candy that is meant for children. So whatever you think about the moral nastiness of the rich, take that, multiply it by the number of Mercedes and Lexuses that cut you off, and you're still short of the mark. In fact, those Mercedes and Lexuses are more likely to cut you off than Hondas or Fords: Studies have shown that people who drive expensive cars are more prone to run stop signs and cut off other motorists .

The rich are the worst tax evaders, and, as The Washington Post has detailed, they are hiding vast sums from public scrutiny in secret overseas bank accounts.

They also give proportionally less to charity -- not surprising, since they exhibit significantly less compassion and empathy toward suffering people. Studies also find that members of the upper class are worse than ordinary folks at "reading" people' s emotions and are far more likely to be disengaged from the people with whom they are interacting -- instead absorbed in doodling, checking their phones or what have you. Some studies go even further, suggesting that rich people, especially stockbrokers and their ilk (such as venture capitalists, whom we once called "robber barons"), are more competitive, impulsive and reckless than medically diagnosed psychopaths. And by the way, those vices do not make them better entrepreneurs; they just have Mommy and Daddy's bank accounts (in New York or the Cayman Islands) to fall back on when they fail.

Indeed, luxuries may numb you to other people -- that Louis Vuitton bag may be a minor league Ring of Sauron . Some studies go so far as to suggest that simply being around great material wealth makes people less willing to share . That's right: Vast sums of money poison not only those who possess them but even those who are merely around them. This helps explain why the nasty ethos of Wall Street has percolated down, including to our politics (though we really didn't need much help there).

So the rich are more likely to be despicable characters. And, as is typically the case with the morally malformed, the first victims of the rich are the rich themselves. Because they often let money buy their happiness and value themselves for their wealth instead of anything meaningful, they are, by extension, more likely to allow other aspects of their lives to atrophy. They seem to have a hard time enjoying simple things, savoring the everyday experiences that make so much of life worthwhile. Because they have lower levels of empathy, they have fewer opportunities to practice acts of compassion -- which studies suggest give people a great deal of pleasure . They tend to believe that people have different financial destinies because of who they essentially are, so they believe that they deserve their wealth , thus dampening their capacity for gratitude, a quality that has been shown to significantly enhance our sense of well-being. All of this seems to make the rich more susceptible to loneliness; they may be more prone to suicide, as well.

How did we lose sight of the ancient wisdom about wealth, especially given its ample evidencing in recent studies?

Some will say that we have not entirely forgotten it and that we do complain about wealth today, at least occasionally. Think, they'll say, about Occupy Wall Street; the blowback after Mitt Romney's comment about the "47 percent"; how George W. Bush painted John Kerry as out of touch. But think again: By and large, those complaints were not about wealth per se but about corrupt wealth -- about wealth "gone wrong" and about unfairness. The idea that there is no way for the vast accumulation of money to "go right" is hardly anywhere to be seen.

Getting here wasn't straightforward. Wealth has arguably been seen as less threatening to one's moral health since the Reformation, after which material success was sometimes taken as evidence of divine election. But extreme wealth remained morally suspect, with the rich bearing particular scrutiny and stigmatization during periods like the Gilded Age. This stigma persisted until relatively recently; only in the 1970s did political shifts cause executive salaries skyrocket, and the current effectively unprecedented inequality in income (and wealth) begin to appear, without any significant public complaint or lament.

The story of how a stigma fades is always murky, but contributing factors are not hard to identify. For one, think tanks have become increasingly partisan over the past several decades, particularly on the right: Certain conservative institutions, enjoying the backing of billionaires such as the Koch brothers, have thrown a ton of money at pseudo-academics and "thought leaders" to normalize and legitimate obscene piles of lucre. They produced arguments that suggest that high salaries naturally flowed from extreme talent and merit, thus baptizing wealth as simply some excellent people's wholly legitimate rewards. These arguments were happily regurgitated by conservative media figures and politicians, eventually seeping into the broader public and replacing the folk wisdom of yore. But it is hard to argue that a company's top earners are literally hundreds of times more talented than the lowest-paid employees.

As stratospheric salaries became increasingly common, and as the stigma of wildly disproportionate pay faded, the moral hazards of wealth were largely forgotten. But it's time to put the apologists for plutocracy back on the defensive, where they belong -- not least for their own sake. After all, the Buddha, Aristotle, Jesus, the Koran, Jimmy Stewart, Pope Francis and now even science all agree: If you are wealthy and are reading this, give away your money as fast as you can.