Parents of public school students probably wouldn't appreciate being grouped with criminals. (Photo: Courtesy of Kennard Williams)

How Budget Austerity Puts Public School Parents On Par With Criminals

Now you tell me, who is the criminal here?

In researching an upcoming article I'm writing about the St. Louis school system, and the district's ongoing funding crisis, I came across an astonishing example of who wins and who loses in current approaches to government budget balancing.

As a local St. Louis reporter tells it, during a public meeting about a proposed new $130 million 34-story apartment building in the city, alderman Joe Roddy used a slideshow to make a case for why the city should give the developers 15 years of reduced property taxes, a $10 million subsidy, in exchange for some additional retail space and 305 high-end, luxury apartments downtown.

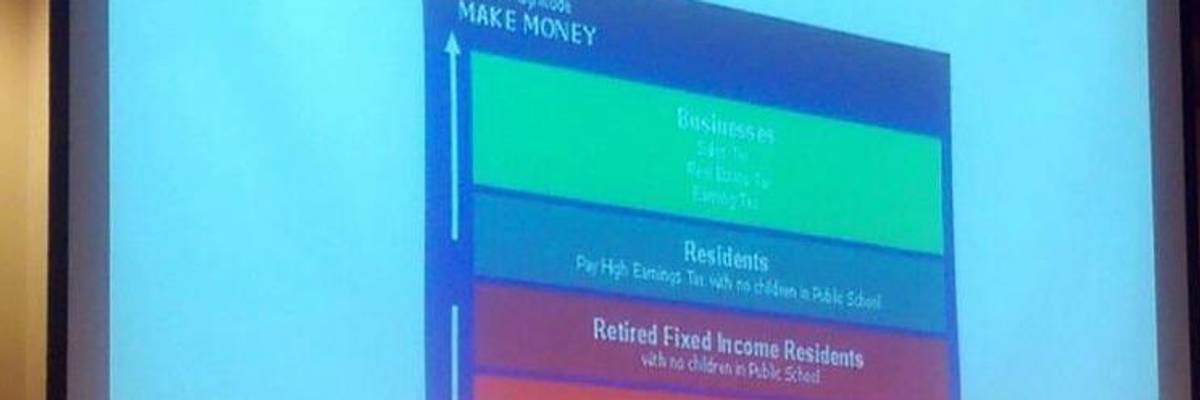

In a slide show titled "How the City Makes & Spends Money," Roddy, a Democrat mind you, laid out a hierarchy of those who "make money" for the city at the top and those who cause the city to "spend money" at the bottom. At the top of his slide were businesses. In the middle were residents with no children and retirees. And at the very bottom - in the tier of city dwellers who place the biggest financial burden on government - were "criminals and residents with children in public school."

When told that some might take offense at equating families with children needing free public schools to criminals, Roddy countered that the project would "target tenants who are young professionals without children. Attracting that demographic to the city is crucial, he says, and after the tax abatement ends, the revenue windfall for the city will be significant."

By the way, St. Louis has a history of extending tax abatements for developers to longer terms.

But the thrust of Roddy's remarks is well understood by all - in a budget environment of forced scarcity, there are increasingly strong demarcations between winners and losers, and parents who plan on sending children to free public schools are increasingly losers.

To be fair to Roddy, a great deal of St. Louis's financial constraints, particularly in relation to the city's ability to cover the cost of education, is the fault of the state of Missouri.

A 2015 accounting of state school funding found Missouri is "underfunding its K-12 schools by $656 million statewide, nearly 20 percent below the required level." The budget situation for families with children has not improved a lot since then, with this year's installment cutting spending on school buses, higher education, and social services.

Missouri is one of 27 states that spends less on education than it did in 2008.

The severity of Missouri's budget austerity seems specifically targeted at districts like St. Louis that happen to be stuck with lots of low-income families with children (Where would they fall in Roddy's hierarchy?).

A 2016 study conducted by NPR found that St. Louis schools on average spend considerably less per student compared to the highest spending districts in the St. Louis area.

Another more recent analysis by EdBuild finds St. Louis schools have a cost adjusted revenue per student that is nine percent below Missouri's average. The district gets only 35 percent of its revenue from the state even though the district is challenged to educate a student population in which 68 percent are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, a common measurement of poverty.

The trend of financial inequity for St. Louis schools is worsening, according to Rutgers University professor Bruce Baker, who finds that the district, since 1995, is increasingly at a funding disadvantage compared to the rest of the state.

It's not hard to see how this is going to play out for parents.

To pay for the costs of crime, under-funded local governments are "increasing fines and fees associated with the criminal justice system," according to a report by NPR in 2014.

One community where court fines and fees "skyrocketed" to levels that made them a major revenue generator for local government is next door to St. Louis - Ferguson, Missouri, where, you recall, 18 year-old Michel Brown was gunned down by local police nearly three years ago.

As it is for the accused in the criminal justice system, parents in local schools are having to bear more of the burden of education costs.

According to an annual report, known as the Backpack Index, that calculates the average cost of school supplies and school fees, parents will have to pick up more of the tab if they want their children to participate fully in school.

The annual cost to parents is significant at a time when the majority of school children come from households in poverty: $662 for elementary school children, $1,001 for middle school children, and $1,489 for high school students.

A detail highlighted by NBC's report on the Backpack Index notes that the biggest spike in direct costs to parents comes from fees charged for activities like school fieldtrips, art and music programs, and athletics. These fees far exceed costs for items like backpacks, pens, and graphing calculators.

Families with children in elementary schools can expect over $30 on average in school fees. For children in middle school, the average cost of fees climbs to $195 for athletics $75 for field trips, and $42 for other school fees. In high school, the fees spike much higher to $375 for athletic (often called "pay to play fees"), $285 for musical instrumentals, $80 to participate in band, and $60 in other school fees. Also in high school, the fees extend to academic courses including participating in Advanced Placement classes, which more schools emphasize students participate in. The average fee for testing related to these courses is $92 and the costs of materials to prepare for these tests, as well as SAT tests, tops $52.

In 2011, I spotlighted the practice of charging parents direct fees for school programs in five states - Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, and Pennsylvania - and connected the rationale for the fees to austerity budgets.

I noted that schools have an obligation to work with all of the varying interests and abilities of students by offering sports, clubs, after-school activities, service learning, and other programs. But states that continually under-fund education pressure schools to shift the burden of these programs from a shared cost of the community onto only those families who need the services.

The problem is getting worse.

In North Carolina, the recently passed state budget again leaves schools woefully short of what they need, and now state administrators are scrambling to pass down the millions in education cuts.

"On the chopping block," reports left-leaning watchdog NC Policy Watch, "include offices that provide services and support for local school districts, including intervention efforts in low-performing regions."

In what appears to be an effort to twist the knife deeper, "the state budget also bars school board members from making up the lost cash with transfers from various GOP-backed education initiatives, including the controversial Innovation School District--which provides for charter takeovers of low-performing schools--and other programs such as Teach for America, Read to Achieve, and positions in the superintendent's office."

In the meantime, NC's budget has winners too, as all budget documents do: "Lawmakers continued to set aside millions for a massive expansion of a private school voucher program. The state is expected to spend $45 million on the program this year, with the plan to expand the annual allocation to $145 million in the next decade."

Now you tell me, who is the criminal here?

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In researching an upcoming article I'm writing about the St. Louis school system, and the district's ongoing funding crisis, I came across an astonishing example of who wins and who loses in current approaches to government budget balancing.

As a local St. Louis reporter tells it, during a public meeting about a proposed new $130 million 34-story apartment building in the city, alderman Joe Roddy used a slideshow to make a case for why the city should give the developers 15 years of reduced property taxes, a $10 million subsidy, in exchange for some additional retail space and 305 high-end, luxury apartments downtown.

In a slide show titled "How the City Makes & Spends Money," Roddy, a Democrat mind you, laid out a hierarchy of those who "make money" for the city at the top and those who cause the city to "spend money" at the bottom. At the top of his slide were businesses. In the middle were residents with no children and retirees. And at the very bottom - in the tier of city dwellers who place the biggest financial burden on government - were "criminals and residents with children in public school."

When told that some might take offense at equating families with children needing free public schools to criminals, Roddy countered that the project would "target tenants who are young professionals without children. Attracting that demographic to the city is crucial, he says, and after the tax abatement ends, the revenue windfall for the city will be significant."

By the way, St. Louis has a history of extending tax abatements for developers to longer terms.

But the thrust of Roddy's remarks is well understood by all - in a budget environment of forced scarcity, there are increasingly strong demarcations between winners and losers, and parents who plan on sending children to free public schools are increasingly losers.

To be fair to Roddy, a great deal of St. Louis's financial constraints, particularly in relation to the city's ability to cover the cost of education, is the fault of the state of Missouri.

A 2015 accounting of state school funding found Missouri is "underfunding its K-12 schools by $656 million statewide, nearly 20 percent below the required level." The budget situation for families with children has not improved a lot since then, with this year's installment cutting spending on school buses, higher education, and social services.

Missouri is one of 27 states that spends less on education than it did in 2008.

The severity of Missouri's budget austerity seems specifically targeted at districts like St. Louis that happen to be stuck with lots of low-income families with children (Where would they fall in Roddy's hierarchy?).

A 2016 study conducted by NPR found that St. Louis schools on average spend considerably less per student compared to the highest spending districts in the St. Louis area.

Another more recent analysis by EdBuild finds St. Louis schools have a cost adjusted revenue per student that is nine percent below Missouri's average. The district gets only 35 percent of its revenue from the state even though the district is challenged to educate a student population in which 68 percent are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, a common measurement of poverty.

The trend of financial inequity for St. Louis schools is worsening, according to Rutgers University professor Bruce Baker, who finds that the district, since 1995, is increasingly at a funding disadvantage compared to the rest of the state.

It's not hard to see how this is going to play out for parents.

To pay for the costs of crime, under-funded local governments are "increasing fines and fees associated with the criminal justice system," according to a report by NPR in 2014.

One community where court fines and fees "skyrocketed" to levels that made them a major revenue generator for local government is next door to St. Louis - Ferguson, Missouri, where, you recall, 18 year-old Michel Brown was gunned down by local police nearly three years ago.

As it is for the accused in the criminal justice system, parents in local schools are having to bear more of the burden of education costs.

According to an annual report, known as the Backpack Index, that calculates the average cost of school supplies and school fees, parents will have to pick up more of the tab if they want their children to participate fully in school.

The annual cost to parents is significant at a time when the majority of school children come from households in poverty: $662 for elementary school children, $1,001 for middle school children, and $1,489 for high school students.

A detail highlighted by NBC's report on the Backpack Index notes that the biggest spike in direct costs to parents comes from fees charged for activities like school fieldtrips, art and music programs, and athletics. These fees far exceed costs for items like backpacks, pens, and graphing calculators.

Families with children in elementary schools can expect over $30 on average in school fees. For children in middle school, the average cost of fees climbs to $195 for athletics $75 for field trips, and $42 for other school fees. In high school, the fees spike much higher to $375 for athletic (often called "pay to play fees"), $285 for musical instrumentals, $80 to participate in band, and $60 in other school fees. Also in high school, the fees extend to academic courses including participating in Advanced Placement classes, which more schools emphasize students participate in. The average fee for testing related to these courses is $92 and the costs of materials to prepare for these tests, as well as SAT tests, tops $52.

In 2011, I spotlighted the practice of charging parents direct fees for school programs in five states - Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, and Pennsylvania - and connected the rationale for the fees to austerity budgets.

I noted that schools have an obligation to work with all of the varying interests and abilities of students by offering sports, clubs, after-school activities, service learning, and other programs. But states that continually under-fund education pressure schools to shift the burden of these programs from a shared cost of the community onto only those families who need the services.

The problem is getting worse.

In North Carolina, the recently passed state budget again leaves schools woefully short of what they need, and now state administrators are scrambling to pass down the millions in education cuts.

"On the chopping block," reports left-leaning watchdog NC Policy Watch, "include offices that provide services and support for local school districts, including intervention efforts in low-performing regions."

In what appears to be an effort to twist the knife deeper, "the state budget also bars school board members from making up the lost cash with transfers from various GOP-backed education initiatives, including the controversial Innovation School District--which provides for charter takeovers of low-performing schools--and other programs such as Teach for America, Read to Achieve, and positions in the superintendent's office."

In the meantime, NC's budget has winners too, as all budget documents do: "Lawmakers continued to set aside millions for a massive expansion of a private school voucher program. The state is expected to spend $45 million on the program this year, with the plan to expand the annual allocation to $145 million in the next decade."

Now you tell me, who is the criminal here?

In researching an upcoming article I'm writing about the St. Louis school system, and the district's ongoing funding crisis, I came across an astonishing example of who wins and who loses in current approaches to government budget balancing.

As a local St. Louis reporter tells it, during a public meeting about a proposed new $130 million 34-story apartment building in the city, alderman Joe Roddy used a slideshow to make a case for why the city should give the developers 15 years of reduced property taxes, a $10 million subsidy, in exchange for some additional retail space and 305 high-end, luxury apartments downtown.

In a slide show titled "How the City Makes & Spends Money," Roddy, a Democrat mind you, laid out a hierarchy of those who "make money" for the city at the top and those who cause the city to "spend money" at the bottom. At the top of his slide were businesses. In the middle were residents with no children and retirees. And at the very bottom - in the tier of city dwellers who place the biggest financial burden on government - were "criminals and residents with children in public school."

When told that some might take offense at equating families with children needing free public schools to criminals, Roddy countered that the project would "target tenants who are young professionals without children. Attracting that demographic to the city is crucial, he says, and after the tax abatement ends, the revenue windfall for the city will be significant."

By the way, St. Louis has a history of extending tax abatements for developers to longer terms.

But the thrust of Roddy's remarks is well understood by all - in a budget environment of forced scarcity, there are increasingly strong demarcations between winners and losers, and parents who plan on sending children to free public schools are increasingly losers.

To be fair to Roddy, a great deal of St. Louis's financial constraints, particularly in relation to the city's ability to cover the cost of education, is the fault of the state of Missouri.

A 2015 accounting of state school funding found Missouri is "underfunding its K-12 schools by $656 million statewide, nearly 20 percent below the required level." The budget situation for families with children has not improved a lot since then, with this year's installment cutting spending on school buses, higher education, and social services.

Missouri is one of 27 states that spends less on education than it did in 2008.

The severity of Missouri's budget austerity seems specifically targeted at districts like St. Louis that happen to be stuck with lots of low-income families with children (Where would they fall in Roddy's hierarchy?).

A 2016 study conducted by NPR found that St. Louis schools on average spend considerably less per student compared to the highest spending districts in the St. Louis area.

Another more recent analysis by EdBuild finds St. Louis schools have a cost adjusted revenue per student that is nine percent below Missouri's average. The district gets only 35 percent of its revenue from the state even though the district is challenged to educate a student population in which 68 percent are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, a common measurement of poverty.

The trend of financial inequity for St. Louis schools is worsening, according to Rutgers University professor Bruce Baker, who finds that the district, since 1995, is increasingly at a funding disadvantage compared to the rest of the state.

It's not hard to see how this is going to play out for parents.

To pay for the costs of crime, under-funded local governments are "increasing fines and fees associated with the criminal justice system," according to a report by NPR in 2014.

One community where court fines and fees "skyrocketed" to levels that made them a major revenue generator for local government is next door to St. Louis - Ferguson, Missouri, where, you recall, 18 year-old Michel Brown was gunned down by local police nearly three years ago.

As it is for the accused in the criminal justice system, parents in local schools are having to bear more of the burden of education costs.

According to an annual report, known as the Backpack Index, that calculates the average cost of school supplies and school fees, parents will have to pick up more of the tab if they want their children to participate fully in school.

The annual cost to parents is significant at a time when the majority of school children come from households in poverty: $662 for elementary school children, $1,001 for middle school children, and $1,489 for high school students.

A detail highlighted by NBC's report on the Backpack Index notes that the biggest spike in direct costs to parents comes from fees charged for activities like school fieldtrips, art and music programs, and athletics. These fees far exceed costs for items like backpacks, pens, and graphing calculators.

Families with children in elementary schools can expect over $30 on average in school fees. For children in middle school, the average cost of fees climbs to $195 for athletics $75 for field trips, and $42 for other school fees. In high school, the fees spike much higher to $375 for athletic (often called "pay to play fees"), $285 for musical instrumentals, $80 to participate in band, and $60 in other school fees. Also in high school, the fees extend to academic courses including participating in Advanced Placement classes, which more schools emphasize students participate in. The average fee for testing related to these courses is $92 and the costs of materials to prepare for these tests, as well as SAT tests, tops $52.

In 2011, I spotlighted the practice of charging parents direct fees for school programs in five states - Arizona, Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, and Pennsylvania - and connected the rationale for the fees to austerity budgets.

I noted that schools have an obligation to work with all of the varying interests and abilities of students by offering sports, clubs, after-school activities, service learning, and other programs. But states that continually under-fund education pressure schools to shift the burden of these programs from a shared cost of the community onto only those families who need the services.

The problem is getting worse.

In North Carolina, the recently passed state budget again leaves schools woefully short of what they need, and now state administrators are scrambling to pass down the millions in education cuts.

"On the chopping block," reports left-leaning watchdog NC Policy Watch, "include offices that provide services and support for local school districts, including intervention efforts in low-performing regions."

In what appears to be an effort to twist the knife deeper, "the state budget also bars school board members from making up the lost cash with transfers from various GOP-backed education initiatives, including the controversial Innovation School District--which provides for charter takeovers of low-performing schools--and other programs such as Teach for America, Read to Achieve, and positions in the superintendent's office."

In the meantime, NC's budget has winners too, as all budget documents do: "Lawmakers continued to set aside millions for a massive expansion of a private school voucher program. The state is expected to spend $45 million on the program this year, with the plan to expand the annual allocation to $145 million in the next decade."

Now you tell me, who is the criminal here?