What Slavery, Ordeals, Duels and Lynching Can Teach us About Abolishing War

When it comes to war, deja vu can be a depressing thing. With the U.S. military in Iraq once again, this time to battle Islamic State fighters, it is tempting to see the cycle of war as endless. Over two millennia ago, Thucydides wrote that "peace is merely an armistice in a war that is continuously going on." But what if he had it wrong? What if we can actually end war once and for all, much as we did other violent practices once thought impossible to abolish?

A world without chattel slavery was inconceivable for almost all of recorded human history. From around 10,000 B.C., it grew to become a pervasive global institution, existing, as the historian Orlando Patterson writes, "in every region of the world, at all levels of sociopolitical development, and among all major ethnic groups." While isolated slave revolts or calls to improve the living conditions of particular slaves did pop up here and there, slavery itself existed as an unquestioned and normal part of the human condition for millennia. It wasn't until only around 250 years ago that a movement arose to end it as such -- to abolish slavery as an institution wherever it existed. Chattel slavery had been around for almost 120 centuries, yet over the course of just one, this movement managed to abolish it from almost every nation on earth.

Trials by ordeal and combat dominated European judicial proceedings for between 500 and 1,000 years depending on the region, yet today we look back and find the practice of determining guilt and innocence by fighting to the death or plunging someone's hand into boiling water absurd, even comical. The same goes for the prospect of two accountants resolving a perceived slight at yesterday's staff meeting by taking turns firing guns at each other at dawn in the parking lot, but the formal duel was an integral part of many societies for five centuries. And in the not-too-distant past, it was not unusual for American communities to lynch black men in public displays of agonizing torture and slow death, all accompanied by a festive atmosphere of civic celebration (kids dismissed from school, ice-cream stands, chartered trains for out-of town tourists coming to watch), yet today seeing such a thing in the town square seems unimaginable.

So if it is possible to abolish these forms of long-standing institutionalized violence, can we, as Margaret Mead famously suggests in "Warfare Is Only an Invention - Not a Biological Necessity," do the same for war? Most people answer no. Looking at images from Syria, Gaza, Ukraine or South Sudan, they find the very question ridiculous. For most, war is an inevitable part of the human condition, something that, in the words of President Obama from his 2009 Nobel Peace Prize speech, "appeared with the first man." The conventional view is that human aggression, selfishness and thirst for power mean war will always be with us. Pacifists who reject all war are naive; objecting to its existence, to use General Sherman's imagery, is as foolish as objecting to the existence of thunder storms. Even worse, pacifists are dangerous. Their sentimental and utopian denunciation of all war amounts to a form of unilateral disarmament in the face of those still willing to use it for unjust ends. Since there is no shortage of dictators and warlords ready to use violence as a tool of assault, oppression and plunder, war is and will remain necessary, at least in some cases, to protect the innocent and uphold a just and peaceful order.

Those who find the prospect of war's abolition absurd make a good case. It is difficult to see how we can eliminate something that has been so pervasive for so long, especially something that, while unpleasant, seems sometimes necessary to defend the lives and liberty of innocent persons from those bent on aggression and destruction. What is striking, however, is how much this reasoning echoes that legitimizing earlier forms of institutionalized violence we no longer accept as inevitable or necessary. Looking at the history of these practices, especially the words used at the time to justify them and dismiss their critics, reveals understandings remarkably analogous to war today. Their eventual abolition in spite of this, and the way such abolition unfolded, offers hope that a similar fate may await war, perhaps even sooner than we think.

Natural, inevitable and necessary

Aristotle famously defended slavery as rooted in human nature -- those born with less reason "are by their nature slaves, and it is better for them to be ruled despotically." Augustine argued that slavery, like war, was the inevitable result of human sinfulness and "appointed by that law which enjoins the preservation of the natural order." For those living in slave societies, nothing was more natural. It was just the way the world was and always had been. As the American judge sentencing slaves accused of supporting Denmark Vesey's revolt stated, "Servitude has existed under various forms from the deluge to the present."

Lynching was understood in similar terms. The naturalness of a racial hierarchy and the need to uphold it was endorsed by both religious and scientific authorities of the time. An 1897 article in the Raleigh News and Observer called lynching a "law of nature" that will always be with us, while John Temple, a columnist syndicated across the South, said it "is a fixed and unchangeable law." For lynching's proponents, such as the Newnan Herald and Advertiser, "it would be as easy to check the rise and fall of the ocean's tides" as to end it.

The chronic violence of Medieval Europe made trials by ordeal and combat seem just as inevitable. In societies where oaths were so important, but where human nature guaranteed people could not be trusted to always be truthful under oath, an appeal to God to act as judge was the only option. Duels had a similar logic. The human condition made both assaults on honor and the need to defend it unavoidable; it was only reasonable that men would resort to dueling to settle such conflicts. Samuel Johnson argued that it was as natural to resist an attack on one's reputation as an attack on one's home, and a governor of South Carolina, Lyde Wilson, wrote in his 1838 dueling manual that the practice was justified by "the first law of nature, self-preservation."

Such appeals to the necessity of self-defense were central to justifying all these forms of institutionalized violence. In a speech on the vulnerability of white women on isolated farms that circulated widely in the 1890s, Rebecca Felton declared, "If it takes lynching to protect woman's dearest possession from drunken, raving human beasts, then I say lynch a thousand a week if it becomes necessary." For many white supporters of lynching, there was "no other remedy" against "schemes of hate, of arson, of murder," so it was "necessary and proper" to defend the innocent. Like war, many people found the act of lynching disturbing, but considered it nonetheless essential to protect public safety. While unpleasant, it was, in the words of congressman Hatton Summers of Texas, necessary to "the preservation of the race."

Ordeal of boiling water, illustration from manuscript. Germany cc. 1350-1375. (Wikipedia)

Upholding public order and protecting innocent citizens from violent crime was the core justification of trials by ordeal and combat too. Ordeals in particular were directed most often at those who seemed most threatening -- vagabonds, social outcasts, known criminals. In the words of one advocate, they were necessary to "clean up the land" of violent predators and "win peace for the faithful." Even those subject to ordeals often saw them as the only way to vindicate their own innocence. In 991, a priest, Adalger of Rheims, pleaded his case against a treason accusation by stating that "if any of you doubt this and think me not worthy of belief, then believe the fire, the boiling water, the glowing iron."

Thomas Aquinas, Francisco Suarez, Hugo Grotius, and other just war thinkers defended war and slavery in similar terms. Both were necessary safeguards against threats of violence and disorder in a fallen world. Like war, a just and peaceful order made slavery necessary. It was part of the hierarchy, subordination and toil such an order requires; without slavery, lawlessness and strife would reign. For many 18th- and 19th-century slavery proponents, it was, like war, an unpleasant institution that was nonetheless necessary for self-defense; subjugation was the only way to protect superior races from the savagery and violence of inferior ones. As the Englishman Edward Bancroft put it in his 1769 defense of slavery, "Many things which are repugnant to humanity may be excused on account of their necessity for self-preservation," a sentiment routinely expressed today about war. Slavery was even a matter of national security. In an era when European powers considered it crucial to the profitability of their New World colonies, and that profitability crucial to their economic and military might, slavery was widely viewed as a necessary bulwark against aggressive threats from rival powers.

In dueling societies it was simply accepted that the law was inadequate to defend against some types of attack. Like war, sometimes it was the only option. As one defender put it, in certain situations there was "no other measure of justice left upon the earth but arms." Andrew Jackson's own mother advised him that since the courts held no redress for affairs of honor, he should be prepared to fight duels, advice he enthusiastically followed. Dueling's proponents argued that its presence acted as a deterrent, helping to keep the peace, improve manners and discourage vices such as lying in business dealings, cheating at cards or committing adultery. They commissioned studies showing that societies with dueling were more peaceful and orderly than those without. Like war, dueling also suffered from a unilateral problem: It was hard to avoid if an adversary was intent on it. History is full of duelists not wanting to participate, but seeing no other way to defend themselves. To refuse was to face public scorn, to bring dishonor on themselves and their families, to lose their friends and, in many cases, even their jobs. Just before dying in an 1827 duel, an American named W.G. Graham wrote: "I heartily protest and despise this absurd mode of settling disputes. But what can a poor devil do except bow to the supremacy of custom."

Dismissing critics

Given the extent to which people considered these earlier forms of institutionalized violence natural and inevitable, it is not surprising that their critics were initially dismissed as naive and sentimental dreamers, much like pacifists are today. Early opponents of slavery faced charges of thinking that society could exist without toil and hierarchy, of spinning utopian visions of a world where nobody had to do the hardest work and racial harmony reigned. Thinking a practice that had been central to human existence since the dawn of time could simply disappear was considered the height of foolishness.

In 713, King Luitbrand of Lombard, who suspected trial by combat did not always produce accurate results, still considered trying to eliminate it imprudent nonsense, saying, "We cannot abolish it, notwithstanding its impiety." Similarly, Napoleon's State Council rejected an anti-dueling bill as foolish and unrealistic, arguing that in some situations "it is impossible for a man to vindicate himself otherwise than by a duel." Summing up the popular view of anti-dueling activists, the 19th-century French commentator Jules Janin said those "who have opposed dueling are either fools or cowards." And those calling for an end to lynching were accused by Southern newspapers of the time as engaging in "maudlin sentimentality" and of being "un-American." Even Northern papers such as the New York Herald accused lynching's critics of utopian hypocrisy since they clearly lived in areas "where their wives and daughters are perfectly safe."

Since these earlier forms of institutionalized violence were considered necessary to defend the innocent and uphold order, their critics were not just considered utopian but also dangerous -- they were suggesting a form of unilateral disarmament that would expose society to assault and mayhem. Those who criticized trials by ordeal and combat were accused of denying the power of God and wanting to surrender society to ruffians and oath-breakers. Dueling's critics faced similar charges. They would leave men and women defenseless in the face of attacks on honor. Dueling's abolition would be a threat to social stability, resulting in the loss of key social virtues that had, in the words of one British duelist in 1803, "supported this country for many ages, and she might perish if they were lost."

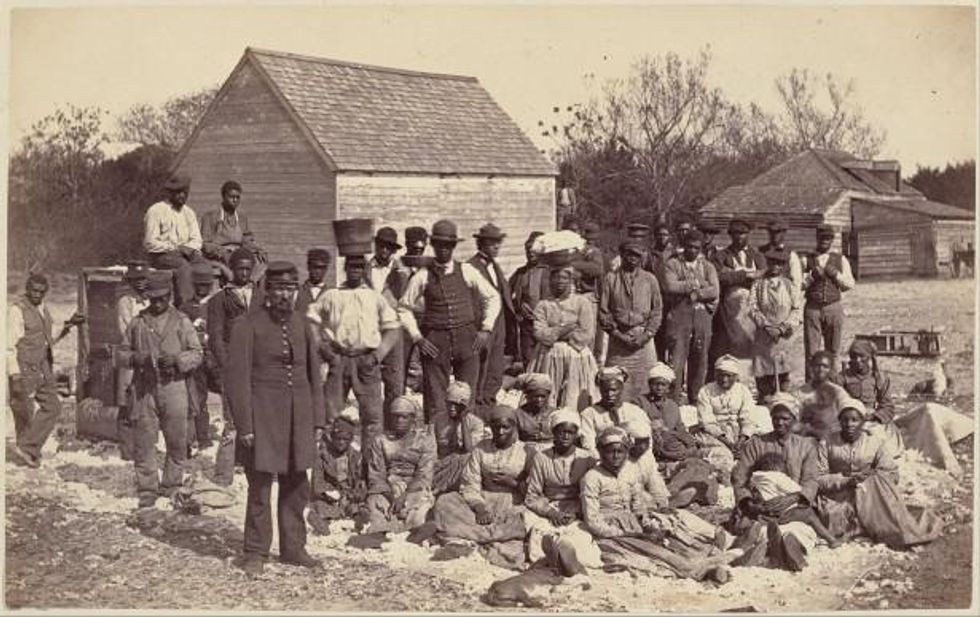

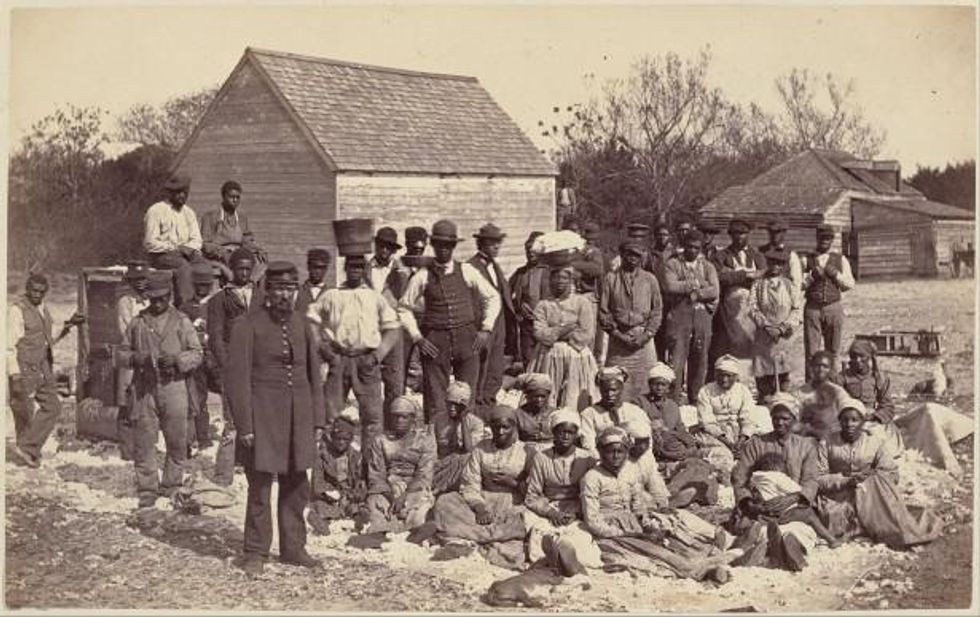

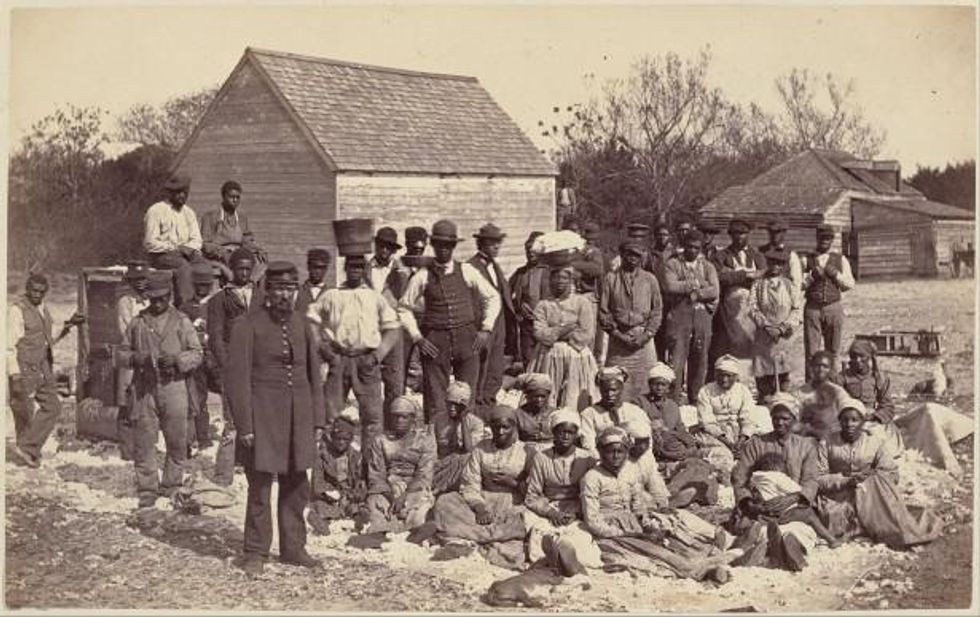

The slaves of General Thomas F. Drayton in 1862. (WIkipedia)

Slavery's defenders accused abolitionists of recklessly putting abstract principles over social order and the security of whites in slave societies. Abolition would bring unchecked Africans murdering white children and raping white women. The Earl of Abingdon wrote, "The Order, and Subordination, and Happiness of the whole habitable Globe is threatened." The rebellion of slaves in Haiti was considered the ultimate rejoinder to abolitionists, the 18th- and 19th-century equivalent of "what about Hitler" that pacifists face today. Lurid accounts of it and similar slave revolts circulated widely to indict abolitionism. One describing the torture and murder of pregnant white women concluded, "Such are thy Triumphs, Philanthropy!"

Given the importance of slavery to geopolitical rivalries, abolitionists also faced charges of being unpatriotic and giving aid and comfort to foreign enemies. John C. Calhoun accused American abolitionists of cooperating in a British plot to steal Texas, and Abel Upshur, a U.S. Secretary of State in the 1840s, said of British abolitionism, "England has ruined her own colonies, and like an unchaste female wishes to see other countries in a similar state."

The language of self-defense also dominated the case against lynching's critics. They were suggesting reckless disarmament, siding with criminals, sacrificing the lives of the innocent on the altar of their moral purity. Anti-lynching legislation was "a bill to encourage rape" that would only pave the way for "the ignorant Negroes of the South" to "commit the foulest of outrages." For Mississippi Sen. Theodore Bilbo, such legislation promised to "open the floodgates of Hell."

The process of abolition

Given how deeply entrenched these other forms of institutionalized violence were, how were they ultimately abolished? In each case, it was a reinforcing cycle of changing cultural attitudes and formal government action, both of which were driven by abolitionist organizations and generations of dedicated activists, that ushered in new social norms and political institutions displacing the older ones. This was a gradual and uneven process, moving in starts and stops. Some areas held out longer than others. And abolition usually left behind vestiges of the practice or gave rise to new forms of institutionalized violence and injustice.

Efforts to end trials by ordeal and combat took centuries. A growing number of theologians and church leaders began to see them as impious, as a presumptuous human attempt to "force God's hand." But even in the face of formal condemnations by popes, such trials continued to flourish across Europe. It was only as the church began to centralize its power and formalize its control over far-flung clergy in the late-Middle Ages that its prohibition of the practice gained traction. Additionally, the rise of lay confession and greater esteem for the sacraments priests controlled gave them alternative sources of social power to replace that which they had exercised by presiding over trials by ordeal and combat.

At the same time, secular authorities in Europe were consolidating their own power over larger territories that would eventually emerge as nation states. Part of this process was formalizing judicial proceedings by eliminating what were coming to be considered chaotic and unpredictable spectacles. New institutional practices emerged to supplant trials by ordeal and combat: the jury system in some places, the inquisitorial system in others, and greater use of written evidence such as contracts. Still needing a way to establish who was lying or telling the truth, authorities now attached greater importance to formal confessions, including those secured under judicial torture, a major form of institutionalized violence that emerged as trials by ordeal and combat waned.

Dueling's decline was also gradual and uneven, ending in some countries by the early-19th century but lasting until World War I in others. In all cases, its fall was marked by a shift in social attitudes. Anti-dueling activists recruited clergy, journalists and military officers into anti-dueling societies that not only raised awareness, but gave those declining to duel a new network of social support. While formerly seen as a serious matter exhibiting virtues such as honor and courage, the public increasingly saw it as an absurd way to settle disputes, one associated with vanity and childish impetuousness. Ridicule, that most fearsome of social sanctions, was now directed at those who dueled rather than those who refused to. In the late-19th century, London newspapers that had formally reported favorably on duels began using words such as "juvenile" and "ridiculous" to describe them. With this shift in public opinion, political authorities became more willing to enforce formerly toothless anti-dueling laws. Judges and juries were now willing to convict those who broke such laws. National militaries, which once cashiered soldiers unwilling to fight duels, now did so against those who fought them.

At the same time, alternatives to dueling emerged. The development of libel and slander laws allowed those whose reputations had been attacked to seek satisfaction in the courts, and the rise of amateur sports such as rugby or boxing afforded young men other venues to prove their courage and physical prowess. The kind of conflicts that had led to duels did not disappear, but now played themselves out in court rooms and boxing rings. Social misbehavior was now more likely to be punished by gossip, severed social relationships, or formal censor under new codes of professional ethics.

For slavery, those working to abolish it managed to create what historian David Brion Davis calls "a profound transformation of moral perception," a change in the consensus view of slavery away from thoughtless acceptance toward revulsion. In country after country, abolitionists forced the public to confront the reality of slavery by dramatizing its cruelty and the humanity of its victims. Anti-slavery activists produced novels ("Uncle Tom's Cabin" being the most famous in the United States), plays and graphic newspaper accounts to drive home slavery's brutality. Most effective were memoirs and public lectures by former slaves such as Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass giving witness to the toll of slavery on particular persons and their families.

Rather than a bulwark of social order, public perceptions of slavery increasingly saw it as lawless and morally corrupting. While this shift in cultural attitudes did not convince everyone, it did give abolitionists enough political traction to dismantle slavery's legal and political framework, to use government power that once sustained slavery to now suppress it, including among those still unwilling to give it up voluntarily. In some cases gradual and in others sudden, sometimes violent and sometimes nonviolent, this abolition process varied widely by country, but taken together it amounted to, in the words of Davis again, "one of the most extraordinary events in history," one that "removed slavery from the list of supposedly inevitable misfortunes of life."

It is important to note that the abolition of slavery did not just unfold within countries, but among them as well; it amounted to a huge international relations challenge. As a global norm against slavery emerged, some countries still considered the institution central to their national interests and refused to end it. In one of the earliest examples of a global prohibition regime, transnational networks of abolition societies pressured the international community, led by the British, to use a mix of sanctions (such as naval blockades and asset seizures) and incentives (such as favorable trade arrangements and diplomatic recognition) to pressure these hold-outs. Such pressure, combined with that coming from within by economic and intellectual elites tired of being treated as international pariahs, eventually forced governments of slave-owning countries to abolish the institution.

Of course, ending a global system of chattel slavery did not end labor exploitation. Vestiges remained in sharecropping, coercive apprenticeship and social caste systems, and human trafficking, child labor and sweatshops still flourish around the world today. It also did not end racial injustice. In the institution's wake, formerly enslaved groups faced, and often still face, discrimination, segregation and new forms of institutionalized violence.

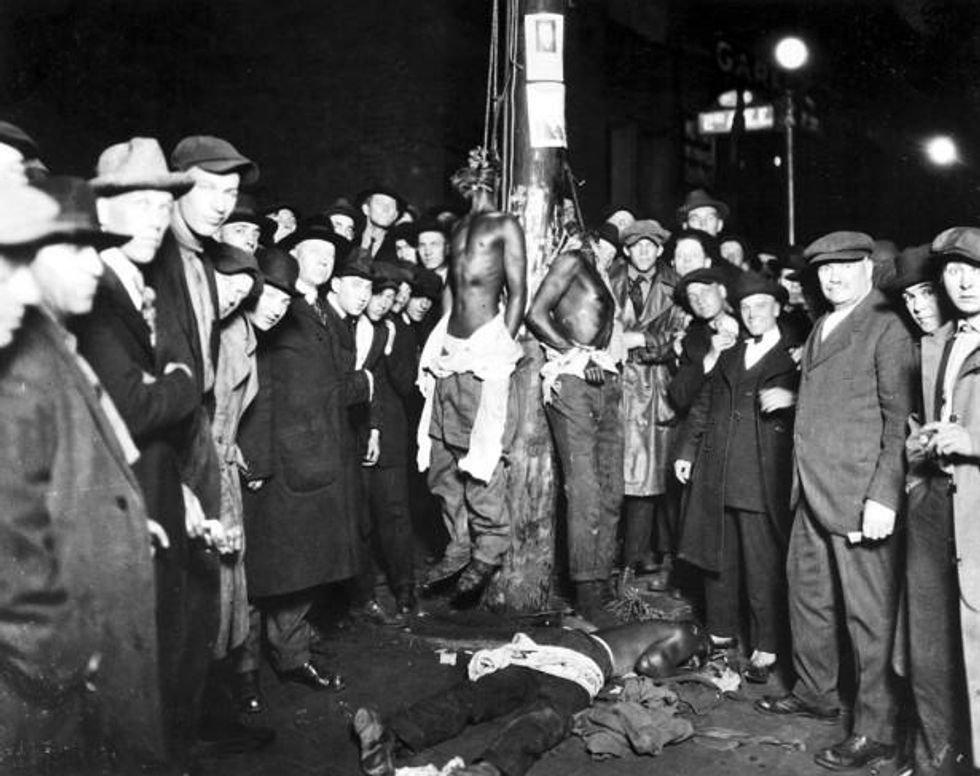

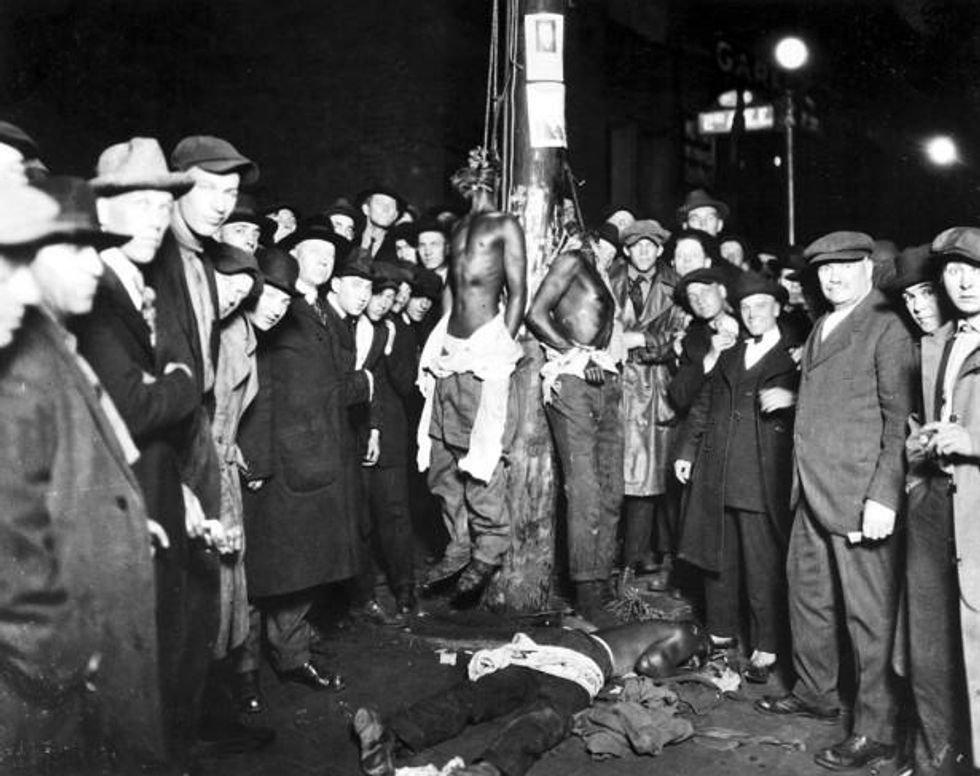

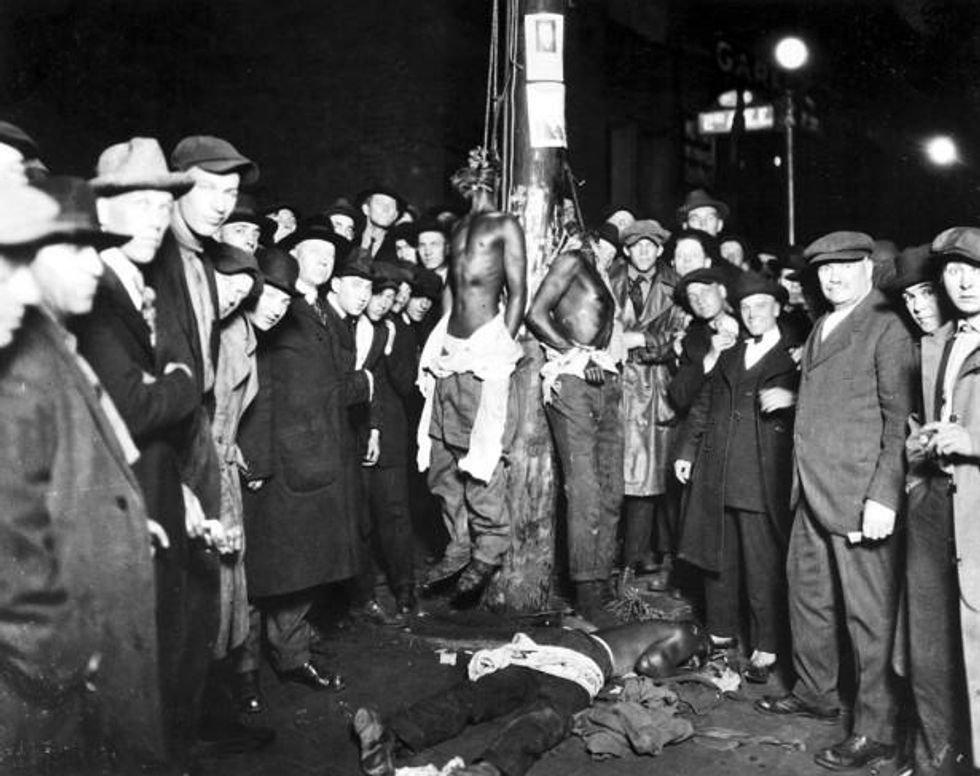

A postcard showing the 1920 Duluth, Minnesota lynchings. (WIkipedia)

One especially vicious form of institutionalized violence that became more prominent on the American scene with slavery's end was lynching. The subsequent movement to abolish it -- to save "black America's body and white America's soul" in the words of the activist James Weldon Johnson -- took generations. Abolitionists mounted a long campaign to open the public's eyes to lynching's brutality, using plays, lectures, radio stories and newspaper ads to hold up, in Johnson's words, "the raw, naked, brutal facts of lynching ... before the eyes of this country until the heart of this nation becomes sick." One especially powerful newspaper ad pointed out that the United States was the only place left on earth where people were still burned at the stake. Activists also played on the public's reverence for American democracy and constitutional government, portraying lynching as lawless and chaotic, with crowds acting as judges, juries and executioners, thus violating national ideals of due process, rule of law and separation of powers. Gradually, more and more Americans came to see lynching as an uncivilized and anachronistic national disgrace. As disgust with lynching slowly spread, economic elites and opinion leaders in the South came to see it as a regional embarrassment, one damaging the South's reputation and hindering its economic progress.

In addition to shifting public attitudes, activists also targeted political institutions. While legislation to ban lynching under federal law never made it out of Congress, anti-lynching organizations pressured state and local officials to move against lynching more aggressively, spreading information about law enforcement tactics designed to effectively disperse lynch mobs. Gradually such officials did act to suppress the practice, first outside the South and eventually in it. And in the absence of a federal anti-lynching statute, activists also pressured the Justice Department to use several long-neglected 19th-centruy laws to prosecute lynching in those areas of the country where local officials still resisted doing so.

Ending lynching meant ending its particular form of violence -- open, public, enjoying wide social participation and legitimacy -- but its abolition certainly did not end hate crimes against African Americans, as infamous cases such as the killings of James Byrd in 1998 and Trayvon Martin in 2012 show. It also didn't eliminate abuse of black citizens at the hands of the police, and soon after lynching's end, an explosion of new criminal justice policies and practices in the mid-to-late 20th century led to the mass incarceration of black men that still exists across the country today.

Lessons for war

What can we learn from looking at these earlier forms of institutionalized violence? First, it is possible to end practices once considered natural, inevitable and necessary. While at the time most people accepted them as just the way the world worked and always would, today we look back and wonder how they could have engaged in such absurd and brutal things.

Second, it was not utopian to imagine and work for a world without these other forms of institutionalized violence because moral progress does not require moral perfection. All these abolitionists were accused of denying human nature, of naively pinning their hopes on a world without conflict, selfishness, treachery or violence. But their success did not depend on changing the human condition, just some human institutions. In a slave-owning society, you didn't have to be a vicious person to own slaves, just as the fact that you don't own slaves today doesn't necessarily make you a virtuous person. Abolishing these other forms of institutionalized violence was certainly a good thing, each a mark of moral progress, but none depended on making people perfectly good. The end of each left a world that still had plenty of conflict, selfishness, treachery and violence, often including new forms of injustice replacing those that had been abolished.

Third, abolishing long-standing and widely-accepted forms of institutionalized violence is an uneven and inelegant process. It is not that one day everyone wakes up and suddenly decides to stop dueling or enslaving or lynching. It takes the hard, patient work of raising social awareness and chipping away at public policies. There is no guarantee of success, but it is possible that such efforts can eventually lead to new social norms and new political institutions that displace and provide alternatives to practices once commonly assumed to be the only option.

These lessons show that abolishing war, while far from certain, is at least possible. Indeed, we may be further along than we realize. Media images can give the impression of pervasive war around the world, but the data on armed conflict paint a different picture. Joshua Goldstein, Steven Pinker and others have detailed the decline in war's frequency and lethality over the last several centuries, a long-term trend that was temporarily interrupted in the early-20th century, but that resumed after World War II and has accelerated since the end of the Cold War. By some measures, the number of people killed in warfare has dropped 75 percent in the last three decades alone, even as the global population increased sharply in the same period.

The long-term decline of warfare is most dramatic in certain types of conflicts. In what the political scientist Robert Jervis calls "the single most striking discontinuity that the history of international politics has anywhere provided," wars between great powers, long the deadliest type, have virtually disappeared. Indeed, interstate wars of any kind, which historically accounted for the majority of wars, are now very rare. None of this is to say that wars have vanished from the earth, or that those that remain, now mainly civil wars within states, don't still kill a great many people, but only that war's global scale is significantly smaller than the historical norm.

If a cycle of changing both social attitudes and political structures led to the abolition of earlier forms of institutionalized violence, something similar may be happening with war. Strict pacifism still appeals to only a small minority of people, but the last century or so has seen the rise of a more widespread cultural aversion to war, even among those who still consider it a tragic necessity under some circumstances. A growing global humanitarianism feeds outrage at images of war's human toll, even if it is on the other side of the world, and skepticism toward war has become more pronounced in many artistic, literary and religious traditions. In his sweeping history of warfare, John Keegan argues that these cultural trends mark "a profound change in civilization's attitude toward war."

The spread of democracy and the rule of law, the rise of nonviolent direct action movements, and economic development have all contributed to war's decline. So too has greater global governance made possible since World War II by a growing web of international institutions -- intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations, treaties and their enforcement regimes, grassroots advocacy groups -- that have pulled nations into closer interdependent relationships with each other. International mediation, arbitration and peacekeeping efforts, while producing some highly visible failures, have also amassed a longer, albeit less well-known, list of successes. While far from perfect, and often messy in their operation, new political structures have arisen in the last 70 years that have proven effective in developing alternatives to warfare. Just as the global community used a mix of sanctions, incentives and international attention to gradually isolate and pressure countries unwilling to give up slavery to do so anyway, it is increasingly well-equipped to do the same for war today.

Many people can't imagine what a world without war would look like. But it isn't actually that hard. It would look a lot like the world today: still lots of injustice, conflict and misery -- just minus warfare. Indeed, many parts of the world already look this way. Most of South and North America, Asia and Europe -- regions embracing the majority of the world's population -- have lots of problems, but wars are not among them. It is really a relatively small group of countries in the Middle East, Eastern Europe bordering Russia, and parts of Africa that account for almost all of the world's armed conflict (as well as a few nations such as the United States that travel to these regions to join in and start new ones). This is certainly significant, but it should not obscure the fact that huge swaths of the globe with long histories of regular warfare seem to have given it up. It is not that these countries no longer have conflicts. They have many. It is just that turning to war to solve them has become as unthinkable as fighting duels over social insults. Consider the fact that collecting outstanding foreign debts was long considered a legitimate reason for war, but even as the Great Recession that began in 2008 brought a debt crisis and sharp political conflict to Europe, nobody expected Germany to invade Greece or France to invade Spain to collect on defaulted loans. The idea strikes us as absurd today, but for most of European history it would have been expected.

Wars still exist, but in John Mueller's influential theory, most may actually represent the "remnants of war," the low-intensity type of civil war, fought by loosely-organized warlords and criminal gangs in failed states, left over after most other types have faded. In slavery's final decades, it was still a brutal institution hanging on in certain regions. Some people still fought duels even in its waning years. Lynching obstinately persisted in some parts of the American South long after the rest of the country had turned against it. Abolition is not a neat and linear process. Its starts and stops, stubborn hold-outs and even reversals along the way can all make it seem futile, even when it is actually close to success. Will this be the case with war? It is impossible to say for sure, but it is certainly possible. We have abolished practices similarly seen as inevitable and necessary. There is no inescapable reason war can't join them.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

When it comes to war, deja vu can be a depressing thing. With the U.S. military in Iraq once again, this time to battle Islamic State fighters, it is tempting to see the cycle of war as endless. Over two millennia ago, Thucydides wrote that "peace is merely an armistice in a war that is continuously going on." But what if he had it wrong? What if we can actually end war once and for all, much as we did other violent practices once thought impossible to abolish?

A world without chattel slavery was inconceivable for almost all of recorded human history. From around 10,000 B.C., it grew to become a pervasive global institution, existing, as the historian Orlando Patterson writes, "in every region of the world, at all levels of sociopolitical development, and among all major ethnic groups." While isolated slave revolts or calls to improve the living conditions of particular slaves did pop up here and there, slavery itself existed as an unquestioned and normal part of the human condition for millennia. It wasn't until only around 250 years ago that a movement arose to end it as such -- to abolish slavery as an institution wherever it existed. Chattel slavery had been around for almost 120 centuries, yet over the course of just one, this movement managed to abolish it from almost every nation on earth.

Trials by ordeal and combat dominated European judicial proceedings for between 500 and 1,000 years depending on the region, yet today we look back and find the practice of determining guilt and innocence by fighting to the death or plunging someone's hand into boiling water absurd, even comical. The same goes for the prospect of two accountants resolving a perceived slight at yesterday's staff meeting by taking turns firing guns at each other at dawn in the parking lot, but the formal duel was an integral part of many societies for five centuries. And in the not-too-distant past, it was not unusual for American communities to lynch black men in public displays of agonizing torture and slow death, all accompanied by a festive atmosphere of civic celebration (kids dismissed from school, ice-cream stands, chartered trains for out-of town tourists coming to watch), yet today seeing such a thing in the town square seems unimaginable.

So if it is possible to abolish these forms of long-standing institutionalized violence, can we, as Margaret Mead famously suggests in "Warfare Is Only an Invention - Not a Biological Necessity," do the same for war? Most people answer no. Looking at images from Syria, Gaza, Ukraine or South Sudan, they find the very question ridiculous. For most, war is an inevitable part of the human condition, something that, in the words of President Obama from his 2009 Nobel Peace Prize speech, "appeared with the first man." The conventional view is that human aggression, selfishness and thirst for power mean war will always be with us. Pacifists who reject all war are naive; objecting to its existence, to use General Sherman's imagery, is as foolish as objecting to the existence of thunder storms. Even worse, pacifists are dangerous. Their sentimental and utopian denunciation of all war amounts to a form of unilateral disarmament in the face of those still willing to use it for unjust ends. Since there is no shortage of dictators and warlords ready to use violence as a tool of assault, oppression and plunder, war is and will remain necessary, at least in some cases, to protect the innocent and uphold a just and peaceful order.

Those who find the prospect of war's abolition absurd make a good case. It is difficult to see how we can eliminate something that has been so pervasive for so long, especially something that, while unpleasant, seems sometimes necessary to defend the lives and liberty of innocent persons from those bent on aggression and destruction. What is striking, however, is how much this reasoning echoes that legitimizing earlier forms of institutionalized violence we no longer accept as inevitable or necessary. Looking at the history of these practices, especially the words used at the time to justify them and dismiss their critics, reveals understandings remarkably analogous to war today. Their eventual abolition in spite of this, and the way such abolition unfolded, offers hope that a similar fate may await war, perhaps even sooner than we think.

Natural, inevitable and necessary

Aristotle famously defended slavery as rooted in human nature -- those born with less reason "are by their nature slaves, and it is better for them to be ruled despotically." Augustine argued that slavery, like war, was the inevitable result of human sinfulness and "appointed by that law which enjoins the preservation of the natural order." For those living in slave societies, nothing was more natural. It was just the way the world was and always had been. As the American judge sentencing slaves accused of supporting Denmark Vesey's revolt stated, "Servitude has existed under various forms from the deluge to the present."

Lynching was understood in similar terms. The naturalness of a racial hierarchy and the need to uphold it was endorsed by both religious and scientific authorities of the time. An 1897 article in the Raleigh News and Observer called lynching a "law of nature" that will always be with us, while John Temple, a columnist syndicated across the South, said it "is a fixed and unchangeable law." For lynching's proponents, such as the Newnan Herald and Advertiser, "it would be as easy to check the rise and fall of the ocean's tides" as to end it.

The chronic violence of Medieval Europe made trials by ordeal and combat seem just as inevitable. In societies where oaths were so important, but where human nature guaranteed people could not be trusted to always be truthful under oath, an appeal to God to act as judge was the only option. Duels had a similar logic. The human condition made both assaults on honor and the need to defend it unavoidable; it was only reasonable that men would resort to dueling to settle such conflicts. Samuel Johnson argued that it was as natural to resist an attack on one's reputation as an attack on one's home, and a governor of South Carolina, Lyde Wilson, wrote in his 1838 dueling manual that the practice was justified by "the first law of nature, self-preservation."

Such appeals to the necessity of self-defense were central to justifying all these forms of institutionalized violence. In a speech on the vulnerability of white women on isolated farms that circulated widely in the 1890s, Rebecca Felton declared, "If it takes lynching to protect woman's dearest possession from drunken, raving human beasts, then I say lynch a thousand a week if it becomes necessary." For many white supporters of lynching, there was "no other remedy" against "schemes of hate, of arson, of murder," so it was "necessary and proper" to defend the innocent. Like war, many people found the act of lynching disturbing, but considered it nonetheless essential to protect public safety. While unpleasant, it was, in the words of congressman Hatton Summers of Texas, necessary to "the preservation of the race."

Ordeal of boiling water, illustration from manuscript. Germany cc. 1350-1375. (Wikipedia)

Upholding public order and protecting innocent citizens from violent crime was the core justification of trials by ordeal and combat too. Ordeals in particular were directed most often at those who seemed most threatening -- vagabonds, social outcasts, known criminals. In the words of one advocate, they were necessary to "clean up the land" of violent predators and "win peace for the faithful." Even those subject to ordeals often saw them as the only way to vindicate their own innocence. In 991, a priest, Adalger of Rheims, pleaded his case against a treason accusation by stating that "if any of you doubt this and think me not worthy of belief, then believe the fire, the boiling water, the glowing iron."

Thomas Aquinas, Francisco Suarez, Hugo Grotius, and other just war thinkers defended war and slavery in similar terms. Both were necessary safeguards against threats of violence and disorder in a fallen world. Like war, a just and peaceful order made slavery necessary. It was part of the hierarchy, subordination and toil such an order requires; without slavery, lawlessness and strife would reign. For many 18th- and 19th-century slavery proponents, it was, like war, an unpleasant institution that was nonetheless necessary for self-defense; subjugation was the only way to protect superior races from the savagery and violence of inferior ones. As the Englishman Edward Bancroft put it in his 1769 defense of slavery, "Many things which are repugnant to humanity may be excused on account of their necessity for self-preservation," a sentiment routinely expressed today about war. Slavery was even a matter of national security. In an era when European powers considered it crucial to the profitability of their New World colonies, and that profitability crucial to their economic and military might, slavery was widely viewed as a necessary bulwark against aggressive threats from rival powers.

In dueling societies it was simply accepted that the law was inadequate to defend against some types of attack. Like war, sometimes it was the only option. As one defender put it, in certain situations there was "no other measure of justice left upon the earth but arms." Andrew Jackson's own mother advised him that since the courts held no redress for affairs of honor, he should be prepared to fight duels, advice he enthusiastically followed. Dueling's proponents argued that its presence acted as a deterrent, helping to keep the peace, improve manners and discourage vices such as lying in business dealings, cheating at cards or committing adultery. They commissioned studies showing that societies with dueling were more peaceful and orderly than those without. Like war, dueling also suffered from a unilateral problem: It was hard to avoid if an adversary was intent on it. History is full of duelists not wanting to participate, but seeing no other way to defend themselves. To refuse was to face public scorn, to bring dishonor on themselves and their families, to lose their friends and, in many cases, even their jobs. Just before dying in an 1827 duel, an American named W.G. Graham wrote: "I heartily protest and despise this absurd mode of settling disputes. But what can a poor devil do except bow to the supremacy of custom."

Dismissing critics

Given the extent to which people considered these earlier forms of institutionalized violence natural and inevitable, it is not surprising that their critics were initially dismissed as naive and sentimental dreamers, much like pacifists are today. Early opponents of slavery faced charges of thinking that society could exist without toil and hierarchy, of spinning utopian visions of a world where nobody had to do the hardest work and racial harmony reigned. Thinking a practice that had been central to human existence since the dawn of time could simply disappear was considered the height of foolishness.

In 713, King Luitbrand of Lombard, who suspected trial by combat did not always produce accurate results, still considered trying to eliminate it imprudent nonsense, saying, "We cannot abolish it, notwithstanding its impiety." Similarly, Napoleon's State Council rejected an anti-dueling bill as foolish and unrealistic, arguing that in some situations "it is impossible for a man to vindicate himself otherwise than by a duel." Summing up the popular view of anti-dueling activists, the 19th-century French commentator Jules Janin said those "who have opposed dueling are either fools or cowards." And those calling for an end to lynching were accused by Southern newspapers of the time as engaging in "maudlin sentimentality" and of being "un-American." Even Northern papers such as the New York Herald accused lynching's critics of utopian hypocrisy since they clearly lived in areas "where their wives and daughters are perfectly safe."

Since these earlier forms of institutionalized violence were considered necessary to defend the innocent and uphold order, their critics were not just considered utopian but also dangerous -- they were suggesting a form of unilateral disarmament that would expose society to assault and mayhem. Those who criticized trials by ordeal and combat were accused of denying the power of God and wanting to surrender society to ruffians and oath-breakers. Dueling's critics faced similar charges. They would leave men and women defenseless in the face of attacks on honor. Dueling's abolition would be a threat to social stability, resulting in the loss of key social virtues that had, in the words of one British duelist in 1803, "supported this country for many ages, and she might perish if they were lost."

The slaves of General Thomas F. Drayton in 1862. (WIkipedia)

Slavery's defenders accused abolitionists of recklessly putting abstract principles over social order and the security of whites in slave societies. Abolition would bring unchecked Africans murdering white children and raping white women. The Earl of Abingdon wrote, "The Order, and Subordination, and Happiness of the whole habitable Globe is threatened." The rebellion of slaves in Haiti was considered the ultimate rejoinder to abolitionists, the 18th- and 19th-century equivalent of "what about Hitler" that pacifists face today. Lurid accounts of it and similar slave revolts circulated widely to indict abolitionism. One describing the torture and murder of pregnant white women concluded, "Such are thy Triumphs, Philanthropy!"

Given the importance of slavery to geopolitical rivalries, abolitionists also faced charges of being unpatriotic and giving aid and comfort to foreign enemies. John C. Calhoun accused American abolitionists of cooperating in a British plot to steal Texas, and Abel Upshur, a U.S. Secretary of State in the 1840s, said of British abolitionism, "England has ruined her own colonies, and like an unchaste female wishes to see other countries in a similar state."

The language of self-defense also dominated the case against lynching's critics. They were suggesting reckless disarmament, siding with criminals, sacrificing the lives of the innocent on the altar of their moral purity. Anti-lynching legislation was "a bill to encourage rape" that would only pave the way for "the ignorant Negroes of the South" to "commit the foulest of outrages." For Mississippi Sen. Theodore Bilbo, such legislation promised to "open the floodgates of Hell."

The process of abolition

Given how deeply entrenched these other forms of institutionalized violence were, how were they ultimately abolished? In each case, it was a reinforcing cycle of changing cultural attitudes and formal government action, both of which were driven by abolitionist organizations and generations of dedicated activists, that ushered in new social norms and political institutions displacing the older ones. This was a gradual and uneven process, moving in starts and stops. Some areas held out longer than others. And abolition usually left behind vestiges of the practice or gave rise to new forms of institutionalized violence and injustice.

Efforts to end trials by ordeal and combat took centuries. A growing number of theologians and church leaders began to see them as impious, as a presumptuous human attempt to "force God's hand." But even in the face of formal condemnations by popes, such trials continued to flourish across Europe. It was only as the church began to centralize its power and formalize its control over far-flung clergy in the late-Middle Ages that its prohibition of the practice gained traction. Additionally, the rise of lay confession and greater esteem for the sacraments priests controlled gave them alternative sources of social power to replace that which they had exercised by presiding over trials by ordeal and combat.

At the same time, secular authorities in Europe were consolidating their own power over larger territories that would eventually emerge as nation states. Part of this process was formalizing judicial proceedings by eliminating what were coming to be considered chaotic and unpredictable spectacles. New institutional practices emerged to supplant trials by ordeal and combat: the jury system in some places, the inquisitorial system in others, and greater use of written evidence such as contracts. Still needing a way to establish who was lying or telling the truth, authorities now attached greater importance to formal confessions, including those secured under judicial torture, a major form of institutionalized violence that emerged as trials by ordeal and combat waned.

Dueling's decline was also gradual and uneven, ending in some countries by the early-19th century but lasting until World War I in others. In all cases, its fall was marked by a shift in social attitudes. Anti-dueling activists recruited clergy, journalists and military officers into anti-dueling societies that not only raised awareness, but gave those declining to duel a new network of social support. While formerly seen as a serious matter exhibiting virtues such as honor and courage, the public increasingly saw it as an absurd way to settle disputes, one associated with vanity and childish impetuousness. Ridicule, that most fearsome of social sanctions, was now directed at those who dueled rather than those who refused to. In the late-19th century, London newspapers that had formally reported favorably on duels began using words such as "juvenile" and "ridiculous" to describe them. With this shift in public opinion, political authorities became more willing to enforce formerly toothless anti-dueling laws. Judges and juries were now willing to convict those who broke such laws. National militaries, which once cashiered soldiers unwilling to fight duels, now did so against those who fought them.

At the same time, alternatives to dueling emerged. The development of libel and slander laws allowed those whose reputations had been attacked to seek satisfaction in the courts, and the rise of amateur sports such as rugby or boxing afforded young men other venues to prove their courage and physical prowess. The kind of conflicts that had led to duels did not disappear, but now played themselves out in court rooms and boxing rings. Social misbehavior was now more likely to be punished by gossip, severed social relationships, or formal censor under new codes of professional ethics.

For slavery, those working to abolish it managed to create what historian David Brion Davis calls "a profound transformation of moral perception," a change in the consensus view of slavery away from thoughtless acceptance toward revulsion. In country after country, abolitionists forced the public to confront the reality of slavery by dramatizing its cruelty and the humanity of its victims. Anti-slavery activists produced novels ("Uncle Tom's Cabin" being the most famous in the United States), plays and graphic newspaper accounts to drive home slavery's brutality. Most effective were memoirs and public lectures by former slaves such as Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass giving witness to the toll of slavery on particular persons and their families.

Rather than a bulwark of social order, public perceptions of slavery increasingly saw it as lawless and morally corrupting. While this shift in cultural attitudes did not convince everyone, it did give abolitionists enough political traction to dismantle slavery's legal and political framework, to use government power that once sustained slavery to now suppress it, including among those still unwilling to give it up voluntarily. In some cases gradual and in others sudden, sometimes violent and sometimes nonviolent, this abolition process varied widely by country, but taken together it amounted to, in the words of Davis again, "one of the most extraordinary events in history," one that "removed slavery from the list of supposedly inevitable misfortunes of life."

It is important to note that the abolition of slavery did not just unfold within countries, but among them as well; it amounted to a huge international relations challenge. As a global norm against slavery emerged, some countries still considered the institution central to their national interests and refused to end it. In one of the earliest examples of a global prohibition regime, transnational networks of abolition societies pressured the international community, led by the British, to use a mix of sanctions (such as naval blockades and asset seizures) and incentives (such as favorable trade arrangements and diplomatic recognition) to pressure these hold-outs. Such pressure, combined with that coming from within by economic and intellectual elites tired of being treated as international pariahs, eventually forced governments of slave-owning countries to abolish the institution.

Of course, ending a global system of chattel slavery did not end labor exploitation. Vestiges remained in sharecropping, coercive apprenticeship and social caste systems, and human trafficking, child labor and sweatshops still flourish around the world today. It also did not end racial injustice. In the institution's wake, formerly enslaved groups faced, and often still face, discrimination, segregation and new forms of institutionalized violence.

A postcard showing the 1920 Duluth, Minnesota lynchings. (WIkipedia)

One especially vicious form of institutionalized violence that became more prominent on the American scene with slavery's end was lynching. The subsequent movement to abolish it -- to save "black America's body and white America's soul" in the words of the activist James Weldon Johnson -- took generations. Abolitionists mounted a long campaign to open the public's eyes to lynching's brutality, using plays, lectures, radio stories and newspaper ads to hold up, in Johnson's words, "the raw, naked, brutal facts of lynching ... before the eyes of this country until the heart of this nation becomes sick." One especially powerful newspaper ad pointed out that the United States was the only place left on earth where people were still burned at the stake. Activists also played on the public's reverence for American democracy and constitutional government, portraying lynching as lawless and chaotic, with crowds acting as judges, juries and executioners, thus violating national ideals of due process, rule of law and separation of powers. Gradually, more and more Americans came to see lynching as an uncivilized and anachronistic national disgrace. As disgust with lynching slowly spread, economic elites and opinion leaders in the South came to see it as a regional embarrassment, one damaging the South's reputation and hindering its economic progress.

In addition to shifting public attitudes, activists also targeted political institutions. While legislation to ban lynching under federal law never made it out of Congress, anti-lynching organizations pressured state and local officials to move against lynching more aggressively, spreading information about law enforcement tactics designed to effectively disperse lynch mobs. Gradually such officials did act to suppress the practice, first outside the South and eventually in it. And in the absence of a federal anti-lynching statute, activists also pressured the Justice Department to use several long-neglected 19th-centruy laws to prosecute lynching in those areas of the country where local officials still resisted doing so.

Ending lynching meant ending its particular form of violence -- open, public, enjoying wide social participation and legitimacy -- but its abolition certainly did not end hate crimes against African Americans, as infamous cases such as the killings of James Byrd in 1998 and Trayvon Martin in 2012 show. It also didn't eliminate abuse of black citizens at the hands of the police, and soon after lynching's end, an explosion of new criminal justice policies and practices in the mid-to-late 20th century led to the mass incarceration of black men that still exists across the country today.

Lessons for war

What can we learn from looking at these earlier forms of institutionalized violence? First, it is possible to end practices once considered natural, inevitable and necessary. While at the time most people accepted them as just the way the world worked and always would, today we look back and wonder how they could have engaged in such absurd and brutal things.

Second, it was not utopian to imagine and work for a world without these other forms of institutionalized violence because moral progress does not require moral perfection. All these abolitionists were accused of denying human nature, of naively pinning their hopes on a world without conflict, selfishness, treachery or violence. But their success did not depend on changing the human condition, just some human institutions. In a slave-owning society, you didn't have to be a vicious person to own slaves, just as the fact that you don't own slaves today doesn't necessarily make you a virtuous person. Abolishing these other forms of institutionalized violence was certainly a good thing, each a mark of moral progress, but none depended on making people perfectly good. The end of each left a world that still had plenty of conflict, selfishness, treachery and violence, often including new forms of injustice replacing those that had been abolished.

Third, abolishing long-standing and widely-accepted forms of institutionalized violence is an uneven and inelegant process. It is not that one day everyone wakes up and suddenly decides to stop dueling or enslaving or lynching. It takes the hard, patient work of raising social awareness and chipping away at public policies. There is no guarantee of success, but it is possible that such efforts can eventually lead to new social norms and new political institutions that displace and provide alternatives to practices once commonly assumed to be the only option.

These lessons show that abolishing war, while far from certain, is at least possible. Indeed, we may be further along than we realize. Media images can give the impression of pervasive war around the world, but the data on armed conflict paint a different picture. Joshua Goldstein, Steven Pinker and others have detailed the decline in war's frequency and lethality over the last several centuries, a long-term trend that was temporarily interrupted in the early-20th century, but that resumed after World War II and has accelerated since the end of the Cold War. By some measures, the number of people killed in warfare has dropped 75 percent in the last three decades alone, even as the global population increased sharply in the same period.

The long-term decline of warfare is most dramatic in certain types of conflicts. In what the political scientist Robert Jervis calls "the single most striking discontinuity that the history of international politics has anywhere provided," wars between great powers, long the deadliest type, have virtually disappeared. Indeed, interstate wars of any kind, which historically accounted for the majority of wars, are now very rare. None of this is to say that wars have vanished from the earth, or that those that remain, now mainly civil wars within states, don't still kill a great many people, but only that war's global scale is significantly smaller than the historical norm.

If a cycle of changing both social attitudes and political structures led to the abolition of earlier forms of institutionalized violence, something similar may be happening with war. Strict pacifism still appeals to only a small minority of people, but the last century or so has seen the rise of a more widespread cultural aversion to war, even among those who still consider it a tragic necessity under some circumstances. A growing global humanitarianism feeds outrage at images of war's human toll, even if it is on the other side of the world, and skepticism toward war has become more pronounced in many artistic, literary and religious traditions. In his sweeping history of warfare, John Keegan argues that these cultural trends mark "a profound change in civilization's attitude toward war."

The spread of democracy and the rule of law, the rise of nonviolent direct action movements, and economic development have all contributed to war's decline. So too has greater global governance made possible since World War II by a growing web of international institutions -- intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations, treaties and their enforcement regimes, grassroots advocacy groups -- that have pulled nations into closer interdependent relationships with each other. International mediation, arbitration and peacekeeping efforts, while producing some highly visible failures, have also amassed a longer, albeit less well-known, list of successes. While far from perfect, and often messy in their operation, new political structures have arisen in the last 70 years that have proven effective in developing alternatives to warfare. Just as the global community used a mix of sanctions, incentives and international attention to gradually isolate and pressure countries unwilling to give up slavery to do so anyway, it is increasingly well-equipped to do the same for war today.

Many people can't imagine what a world without war would look like. But it isn't actually that hard. It would look a lot like the world today: still lots of injustice, conflict and misery -- just minus warfare. Indeed, many parts of the world already look this way. Most of South and North America, Asia and Europe -- regions embracing the majority of the world's population -- have lots of problems, but wars are not among them. It is really a relatively small group of countries in the Middle East, Eastern Europe bordering Russia, and parts of Africa that account for almost all of the world's armed conflict (as well as a few nations such as the United States that travel to these regions to join in and start new ones). This is certainly significant, but it should not obscure the fact that huge swaths of the globe with long histories of regular warfare seem to have given it up. It is not that these countries no longer have conflicts. They have many. It is just that turning to war to solve them has become as unthinkable as fighting duels over social insults. Consider the fact that collecting outstanding foreign debts was long considered a legitimate reason for war, but even as the Great Recession that began in 2008 brought a debt crisis and sharp political conflict to Europe, nobody expected Germany to invade Greece or France to invade Spain to collect on defaulted loans. The idea strikes us as absurd today, but for most of European history it would have been expected.

Wars still exist, but in John Mueller's influential theory, most may actually represent the "remnants of war," the low-intensity type of civil war, fought by loosely-organized warlords and criminal gangs in failed states, left over after most other types have faded. In slavery's final decades, it was still a brutal institution hanging on in certain regions. Some people still fought duels even in its waning years. Lynching obstinately persisted in some parts of the American South long after the rest of the country had turned against it. Abolition is not a neat and linear process. Its starts and stops, stubborn hold-outs and even reversals along the way can all make it seem futile, even when it is actually close to success. Will this be the case with war? It is impossible to say for sure, but it is certainly possible. We have abolished practices similarly seen as inevitable and necessary. There is no inescapable reason war can't join them.

When it comes to war, deja vu can be a depressing thing. With the U.S. military in Iraq once again, this time to battle Islamic State fighters, it is tempting to see the cycle of war as endless. Over two millennia ago, Thucydides wrote that "peace is merely an armistice in a war that is continuously going on." But what if he had it wrong? What if we can actually end war once and for all, much as we did other violent practices once thought impossible to abolish?

A world without chattel slavery was inconceivable for almost all of recorded human history. From around 10,000 B.C., it grew to become a pervasive global institution, existing, as the historian Orlando Patterson writes, "in every region of the world, at all levels of sociopolitical development, and among all major ethnic groups." While isolated slave revolts or calls to improve the living conditions of particular slaves did pop up here and there, slavery itself existed as an unquestioned and normal part of the human condition for millennia. It wasn't until only around 250 years ago that a movement arose to end it as such -- to abolish slavery as an institution wherever it existed. Chattel slavery had been around for almost 120 centuries, yet over the course of just one, this movement managed to abolish it from almost every nation on earth.

Trials by ordeal and combat dominated European judicial proceedings for between 500 and 1,000 years depending on the region, yet today we look back and find the practice of determining guilt and innocence by fighting to the death or plunging someone's hand into boiling water absurd, even comical. The same goes for the prospect of two accountants resolving a perceived slight at yesterday's staff meeting by taking turns firing guns at each other at dawn in the parking lot, but the formal duel was an integral part of many societies for five centuries. And in the not-too-distant past, it was not unusual for American communities to lynch black men in public displays of agonizing torture and slow death, all accompanied by a festive atmosphere of civic celebration (kids dismissed from school, ice-cream stands, chartered trains for out-of town tourists coming to watch), yet today seeing such a thing in the town square seems unimaginable.

So if it is possible to abolish these forms of long-standing institutionalized violence, can we, as Margaret Mead famously suggests in "Warfare Is Only an Invention - Not a Biological Necessity," do the same for war? Most people answer no. Looking at images from Syria, Gaza, Ukraine or South Sudan, they find the very question ridiculous. For most, war is an inevitable part of the human condition, something that, in the words of President Obama from his 2009 Nobel Peace Prize speech, "appeared with the first man." The conventional view is that human aggression, selfishness and thirst for power mean war will always be with us. Pacifists who reject all war are naive; objecting to its existence, to use General Sherman's imagery, is as foolish as objecting to the existence of thunder storms. Even worse, pacifists are dangerous. Their sentimental and utopian denunciation of all war amounts to a form of unilateral disarmament in the face of those still willing to use it for unjust ends. Since there is no shortage of dictators and warlords ready to use violence as a tool of assault, oppression and plunder, war is and will remain necessary, at least in some cases, to protect the innocent and uphold a just and peaceful order.

Those who find the prospect of war's abolition absurd make a good case. It is difficult to see how we can eliminate something that has been so pervasive for so long, especially something that, while unpleasant, seems sometimes necessary to defend the lives and liberty of innocent persons from those bent on aggression and destruction. What is striking, however, is how much this reasoning echoes that legitimizing earlier forms of institutionalized violence we no longer accept as inevitable or necessary. Looking at the history of these practices, especially the words used at the time to justify them and dismiss their critics, reveals understandings remarkably analogous to war today. Their eventual abolition in spite of this, and the way such abolition unfolded, offers hope that a similar fate may await war, perhaps even sooner than we think.

Natural, inevitable and necessary

Aristotle famously defended slavery as rooted in human nature -- those born with less reason "are by their nature slaves, and it is better for them to be ruled despotically." Augustine argued that slavery, like war, was the inevitable result of human sinfulness and "appointed by that law which enjoins the preservation of the natural order." For those living in slave societies, nothing was more natural. It was just the way the world was and always had been. As the American judge sentencing slaves accused of supporting Denmark Vesey's revolt stated, "Servitude has existed under various forms from the deluge to the present."

Lynching was understood in similar terms. The naturalness of a racial hierarchy and the need to uphold it was endorsed by both religious and scientific authorities of the time. An 1897 article in the Raleigh News and Observer called lynching a "law of nature" that will always be with us, while John Temple, a columnist syndicated across the South, said it "is a fixed and unchangeable law." For lynching's proponents, such as the Newnan Herald and Advertiser, "it would be as easy to check the rise and fall of the ocean's tides" as to end it.

The chronic violence of Medieval Europe made trials by ordeal and combat seem just as inevitable. In societies where oaths were so important, but where human nature guaranteed people could not be trusted to always be truthful under oath, an appeal to God to act as judge was the only option. Duels had a similar logic. The human condition made both assaults on honor and the need to defend it unavoidable; it was only reasonable that men would resort to dueling to settle such conflicts. Samuel Johnson argued that it was as natural to resist an attack on one's reputation as an attack on one's home, and a governor of South Carolina, Lyde Wilson, wrote in his 1838 dueling manual that the practice was justified by "the first law of nature, self-preservation."

Such appeals to the necessity of self-defense were central to justifying all these forms of institutionalized violence. In a speech on the vulnerability of white women on isolated farms that circulated widely in the 1890s, Rebecca Felton declared, "If it takes lynching to protect woman's dearest possession from drunken, raving human beasts, then I say lynch a thousand a week if it becomes necessary." For many white supporters of lynching, there was "no other remedy" against "schemes of hate, of arson, of murder," so it was "necessary and proper" to defend the innocent. Like war, many people found the act of lynching disturbing, but considered it nonetheless essential to protect public safety. While unpleasant, it was, in the words of congressman Hatton Summers of Texas, necessary to "the preservation of the race."

Ordeal of boiling water, illustration from manuscript. Germany cc. 1350-1375. (Wikipedia)

Upholding public order and protecting innocent citizens from violent crime was the core justification of trials by ordeal and combat too. Ordeals in particular were directed most often at those who seemed most threatening -- vagabonds, social outcasts, known criminals. In the words of one advocate, they were necessary to "clean up the land" of violent predators and "win peace for the faithful." Even those subject to ordeals often saw them as the only way to vindicate their own innocence. In 991, a priest, Adalger of Rheims, pleaded his case against a treason accusation by stating that "if any of you doubt this and think me not worthy of belief, then believe the fire, the boiling water, the glowing iron."

Thomas Aquinas, Francisco Suarez, Hugo Grotius, and other just war thinkers defended war and slavery in similar terms. Both were necessary safeguards against threats of violence and disorder in a fallen world. Like war, a just and peaceful order made slavery necessary. It was part of the hierarchy, subordination and toil such an order requires; without slavery, lawlessness and strife would reign. For many 18th- and 19th-century slavery proponents, it was, like war, an unpleasant institution that was nonetheless necessary for self-defense; subjugation was the only way to protect superior races from the savagery and violence of inferior ones. As the Englishman Edward Bancroft put it in his 1769 defense of slavery, "Many things which are repugnant to humanity may be excused on account of their necessity for self-preservation," a sentiment routinely expressed today about war. Slavery was even a matter of national security. In an era when European powers considered it crucial to the profitability of their New World colonies, and that profitability crucial to their economic and military might, slavery was widely viewed as a necessary bulwark against aggressive threats from rival powers.

In dueling societies it was simply accepted that the law was inadequate to defend against some types of attack. Like war, sometimes it was the only option. As one defender put it, in certain situations there was "no other measure of justice left upon the earth but arms." Andrew Jackson's own mother advised him that since the courts held no redress for affairs of honor, he should be prepared to fight duels, advice he enthusiastically followed. Dueling's proponents argued that its presence acted as a deterrent, helping to keep the peace, improve manners and discourage vices such as lying in business dealings, cheating at cards or committing adultery. They commissioned studies showing that societies with dueling were more peaceful and orderly than those without. Like war, dueling also suffered from a unilateral problem: It was hard to avoid if an adversary was intent on it. History is full of duelists not wanting to participate, but seeing no other way to defend themselves. To refuse was to face public scorn, to bring dishonor on themselves and their families, to lose their friends and, in many cases, even their jobs. Just before dying in an 1827 duel, an American named W.G. Graham wrote: "I heartily protest and despise this absurd mode of settling disputes. But what can a poor devil do except bow to the supremacy of custom."

Dismissing critics

Given the extent to which people considered these earlier forms of institutionalized violence natural and inevitable, it is not surprising that their critics were initially dismissed as naive and sentimental dreamers, much like pacifists are today. Early opponents of slavery faced charges of thinking that society could exist without toil and hierarchy, of spinning utopian visions of a world where nobody had to do the hardest work and racial harmony reigned. Thinking a practice that had been central to human existence since the dawn of time could simply disappear was considered the height of foolishness.

In 713, King Luitbrand of Lombard, who suspected trial by combat did not always produce accurate results, still considered trying to eliminate it imprudent nonsense, saying, "We cannot abolish it, notwithstanding its impiety." Similarly, Napoleon's State Council rejected an anti-dueling bill as foolish and unrealistic, arguing that in some situations "it is impossible for a man to vindicate himself otherwise than by a duel." Summing up the popular view of anti-dueling activists, the 19th-century French commentator Jules Janin said those "who have opposed dueling are either fools or cowards." And those calling for an end to lynching were accused by Southern newspapers of the time as engaging in "maudlin sentimentality" and of being "un-American." Even Northern papers such as the New York Herald accused lynching's critics of utopian hypocrisy since they clearly lived in areas "where their wives and daughters are perfectly safe."

Since these earlier forms of institutionalized violence were considered necessary to defend the innocent and uphold order, their critics were not just considered utopian but also dangerous -- they were suggesting a form of unilateral disarmament that would expose society to assault and mayhem. Those who criticized trials by ordeal and combat were accused of denying the power of God and wanting to surrender society to ruffians and oath-breakers. Dueling's critics faced similar charges. They would leave men and women defenseless in the face of attacks on honor. Dueling's abolition would be a threat to social stability, resulting in the loss of key social virtues that had, in the words of one British duelist in 1803, "supported this country for many ages, and she might perish if they were lost."

The slaves of General Thomas F. Drayton in 1862. (WIkipedia)

Slavery's defenders accused abolitionists of recklessly putting abstract principles over social order and the security of whites in slave societies. Abolition would bring unchecked Africans murdering white children and raping white women. The Earl of Abingdon wrote, "The Order, and Subordination, and Happiness of the whole habitable Globe is threatened." The rebellion of slaves in Haiti was considered the ultimate rejoinder to abolitionists, the 18th- and 19th-century equivalent of "what about Hitler" that pacifists face today. Lurid accounts of it and similar slave revolts circulated widely to indict abolitionism. One describing the torture and murder of pregnant white women concluded, "Such are thy Triumphs, Philanthropy!"

Given the importance of slavery to geopolitical rivalries, abolitionists also faced charges of being unpatriotic and giving aid and comfort to foreign enemies. John C. Calhoun accused American abolitionists of cooperating in a British plot to steal Texas, and Abel Upshur, a U.S. Secretary of State in the 1840s, said of British abolitionism, "England has ruined her own colonies, and like an unchaste female wishes to see other countries in a similar state."