SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

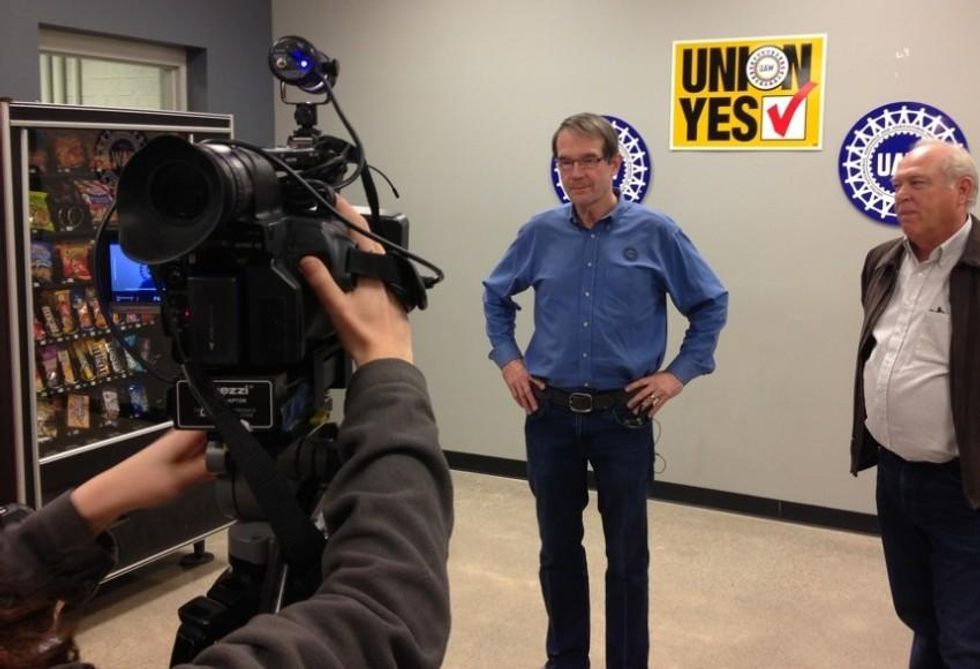

The key to organizing workers in areas like the South, where unions hold little sway, is building trust. From conversations at Volkswagen's Chattanooga plant, I learned that the U.A.W. lost because workers were suspicious of it. Meddling by antiunion politicians was a factor in U.A.W.'s defeat, but that's not the whole story. Many workers who voted against the U.A.W. said they weren't opposed to unions, but they just didn't trust the U.A.W.

Many Chattanooga workers thought the U.A.W. deal ensuring VW's neutrality in the election limited their ability to have a meaningful voice in future contracts. While it's easy to understand why the U.A.W. sought the agreement, given the viciousness with which companies often fight organizing drives, antiunion workers successfully portrayed such a pact as a "backroom deal."

"If unions are to succeed in the South, they need to build trust among workers, not make them feel that deals are being cut behind their backs."

Several unions have agreed to "sweetheart deals" with employers to win neutrality, and in exchange, "pre-agree" to employer sought contract concessions that cap wages before even organizing a single member. A 2008 Wall Street Journal report uncovered how Unite Here and the Service Employees International Union clandestinely negotiated contracts with Sodexo and Aramark without any traditional labor organizing. Under this arrangement, members were unaware that labor contracts were negotiated prior to joining the union. In Chattanooga, antiunion workers successfully persuaded Volkswagen workers, who had previously signed union cards indicating support for the U.A.W., that such a deal undercutting them was already in the works.

Anti-U.A.W. workers distributed flyers attacking U.A.W.'s pact in which it had agreed to "maintain or enhance the cost advantage and other competitive advantages" Volkswagen already enjoys. They claimed the union had already negotiated a contract that would put them in line with U.A.W. new hire rates at the Big Three -- Chrysler, Ford and General Motors -- resulting in wage cuts. There was some truth to this claim. U.A.W.-negotiated Big Three contracts pay new hires significantly less than senior workers with starting salaries less than $16 an hour, slightly more than Chattanooga's starting rate.

Many Chattanooga workers had trouble seeing the upside of joining the U.A.W. Local politicians and outside interest groups, while providing no supporting evidence, claimed that VW would discontinue investing there if U.A.W. won. Scared by such job security threats and unimpressed by U.A.W.'s failure to concretely establish the "upside" of its union, the majority chose the status quo.

By their nature, unions are big, often bureaucratic institutions with sometimes billions of dollars in assets. A lot of workers unfamiliar with unions or already ideologically opposed look at them and say, "I don't know these people. How do I know they won't sell me out?" If unions are going to organize the South, they have to build democratic organizations in which workers make decisions about their workplace - not by signing onto to "sweetheart deals."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

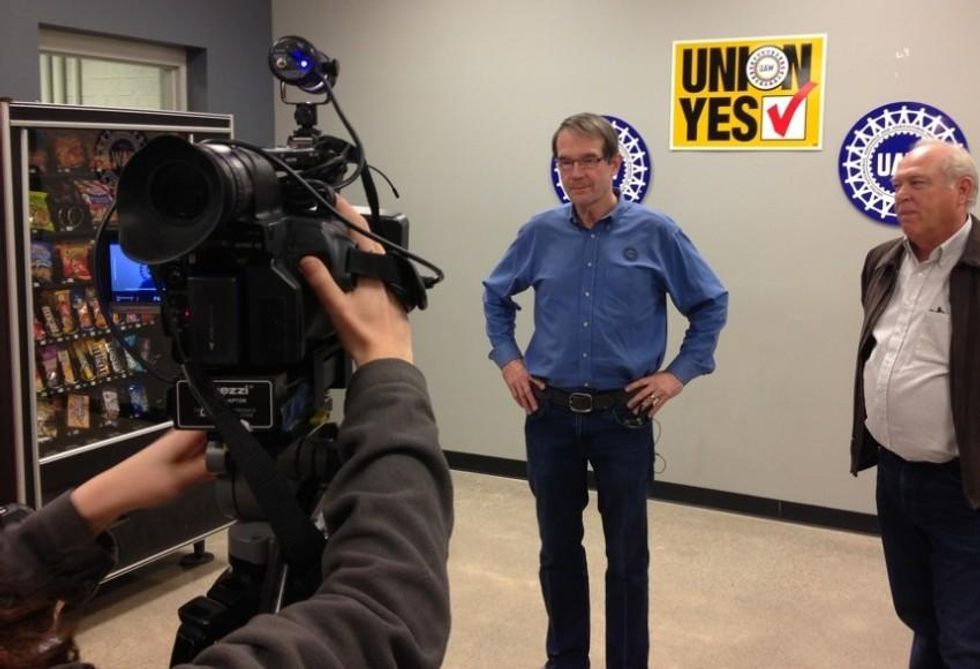

The key to organizing workers in areas like the South, where unions hold little sway, is building trust. From conversations at Volkswagen's Chattanooga plant, I learned that the U.A.W. lost because workers were suspicious of it. Meddling by antiunion politicians was a factor in U.A.W.'s defeat, but that's not the whole story. Many workers who voted against the U.A.W. said they weren't opposed to unions, but they just didn't trust the U.A.W.

Many Chattanooga workers thought the U.A.W. deal ensuring VW's neutrality in the election limited their ability to have a meaningful voice in future contracts. While it's easy to understand why the U.A.W. sought the agreement, given the viciousness with which companies often fight organizing drives, antiunion workers successfully portrayed such a pact as a "backroom deal."

"If unions are to succeed in the South, they need to build trust among workers, not make them feel that deals are being cut behind their backs."

Several unions have agreed to "sweetheart deals" with employers to win neutrality, and in exchange, "pre-agree" to employer sought contract concessions that cap wages before even organizing a single member. A 2008 Wall Street Journal report uncovered how Unite Here and the Service Employees International Union clandestinely negotiated contracts with Sodexo and Aramark without any traditional labor organizing. Under this arrangement, members were unaware that labor contracts were negotiated prior to joining the union. In Chattanooga, antiunion workers successfully persuaded Volkswagen workers, who had previously signed union cards indicating support for the U.A.W., that such a deal undercutting them was already in the works.

Anti-U.A.W. workers distributed flyers attacking U.A.W.'s pact in which it had agreed to "maintain or enhance the cost advantage and other competitive advantages" Volkswagen already enjoys. They claimed the union had already negotiated a contract that would put them in line with U.A.W. new hire rates at the Big Three -- Chrysler, Ford and General Motors -- resulting in wage cuts. There was some truth to this claim. U.A.W.-negotiated Big Three contracts pay new hires significantly less than senior workers with starting salaries less than $16 an hour, slightly more than Chattanooga's starting rate.

Many Chattanooga workers had trouble seeing the upside of joining the U.A.W. Local politicians and outside interest groups, while providing no supporting evidence, claimed that VW would discontinue investing there if U.A.W. won. Scared by such job security threats and unimpressed by U.A.W.'s failure to concretely establish the "upside" of its union, the majority chose the status quo.

By their nature, unions are big, often bureaucratic institutions with sometimes billions of dollars in assets. A lot of workers unfamiliar with unions or already ideologically opposed look at them and say, "I don't know these people. How do I know they won't sell me out?" If unions are going to organize the South, they have to build democratic organizations in which workers make decisions about their workplace - not by signing onto to "sweetheart deals."

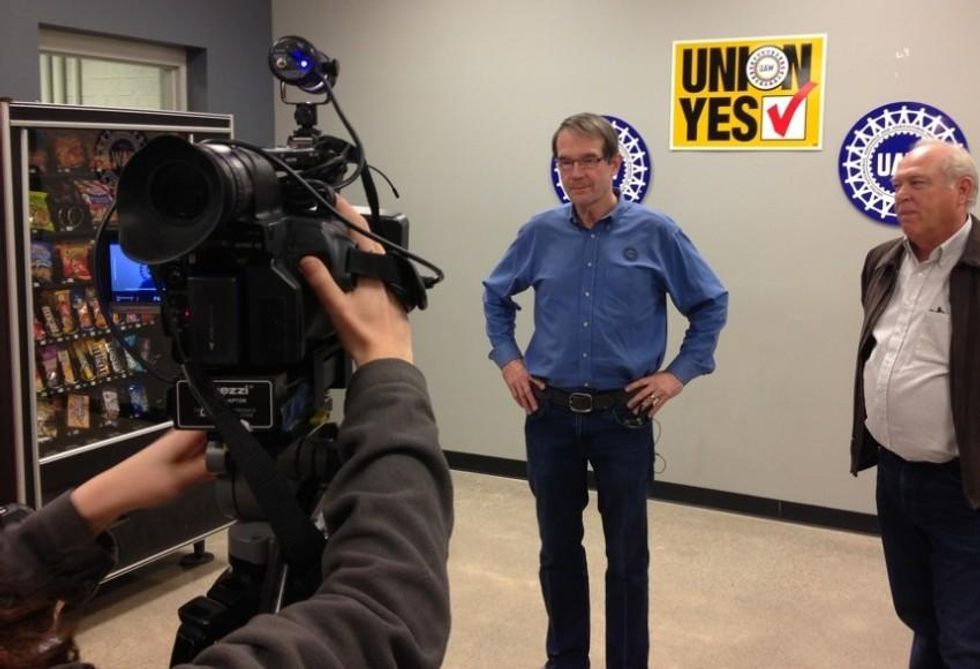

The key to organizing workers in areas like the South, where unions hold little sway, is building trust. From conversations at Volkswagen's Chattanooga plant, I learned that the U.A.W. lost because workers were suspicious of it. Meddling by antiunion politicians was a factor in U.A.W.'s defeat, but that's not the whole story. Many workers who voted against the U.A.W. said they weren't opposed to unions, but they just didn't trust the U.A.W.

Many Chattanooga workers thought the U.A.W. deal ensuring VW's neutrality in the election limited their ability to have a meaningful voice in future contracts. While it's easy to understand why the U.A.W. sought the agreement, given the viciousness with which companies often fight organizing drives, antiunion workers successfully portrayed such a pact as a "backroom deal."

"If unions are to succeed in the South, they need to build trust among workers, not make them feel that deals are being cut behind their backs."

Several unions have agreed to "sweetheart deals" with employers to win neutrality, and in exchange, "pre-agree" to employer sought contract concessions that cap wages before even organizing a single member. A 2008 Wall Street Journal report uncovered how Unite Here and the Service Employees International Union clandestinely negotiated contracts with Sodexo and Aramark without any traditional labor organizing. Under this arrangement, members were unaware that labor contracts were negotiated prior to joining the union. In Chattanooga, antiunion workers successfully persuaded Volkswagen workers, who had previously signed union cards indicating support for the U.A.W., that such a deal undercutting them was already in the works.

Anti-U.A.W. workers distributed flyers attacking U.A.W.'s pact in which it had agreed to "maintain or enhance the cost advantage and other competitive advantages" Volkswagen already enjoys. They claimed the union had already negotiated a contract that would put them in line with U.A.W. new hire rates at the Big Three -- Chrysler, Ford and General Motors -- resulting in wage cuts. There was some truth to this claim. U.A.W.-negotiated Big Three contracts pay new hires significantly less than senior workers with starting salaries less than $16 an hour, slightly more than Chattanooga's starting rate.

Many Chattanooga workers had trouble seeing the upside of joining the U.A.W. Local politicians and outside interest groups, while providing no supporting evidence, claimed that VW would discontinue investing there if U.A.W. won. Scared by such job security threats and unimpressed by U.A.W.'s failure to concretely establish the "upside" of its union, the majority chose the status quo.

By their nature, unions are big, often bureaucratic institutions with sometimes billions of dollars in assets. A lot of workers unfamiliar with unions or already ideologically opposed look at them and say, "I don't know these people. How do I know they won't sell me out?" If unions are going to organize the South, they have to build democratic organizations in which workers make decisions about their workplace - not by signing onto to "sweetheart deals."