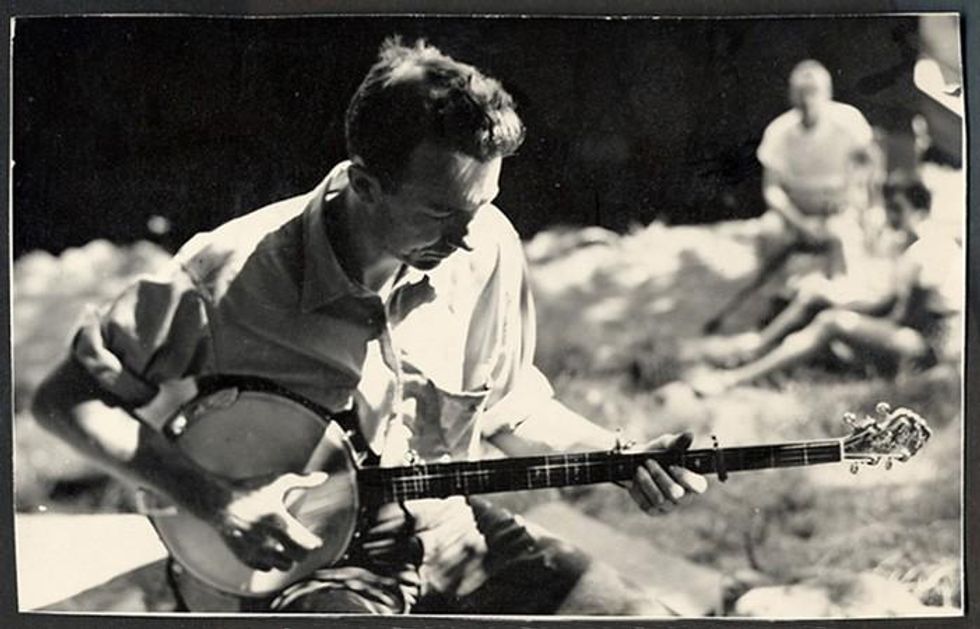

Thank You, Pete Seeger

“We are not afraid…we shall all be free.” Pete Seeger died last night, but the power of his music lives on. One activist pays tribute to another.

My mother was a civil rights and anti-war activist and my father was a GI who organized against the Vietnam War from inside the military. They met while organizing an anti-war Coffee House in Washington DC in 1969. I arrived on the scene two years later.

I grew up learning that everyone must seek justice - whatever that means to you - and it became an integral part of who I am. The music of Pete Seeger was central to that journey. My parents would listen to and sing his music all the time. My night time 'lullabies' were songs like "We Shall Overcome" (one of my mother's favorites) and "Kevin Barry" (one of my dad's).

Listening to these songs as a child I can remember being upset at their lyrics. "I Come and Stand at Every Door", Pete sang, but was the child in the song really a ghost? Where was Hiroshima, and how could children be allowed to die? Did all miners live in the conditions described in "Mrs. Clara Sullivan's Letter?" Why would "John Henry" have to die to "beat a machine." Pete also sang songs especially for children, which really made me think. I learned the meaning of being "ostracized" by listening to "Abiyoyo" before I was even in school, and took the lesson of that song to heart: even if you are counted as excluded, you can still beat giants.

Living in Croton-on-Hudson in upstate New York for much of my childhood, I was lucky enough to see Pete perform at the Clearwater Revival folk music celebrations he organized every year. I can remember his presence, so normal and accessible, and always trying to get everyone to participate. It was not about him, though he was the performer. It was his personality as much as his politics that made him such a transformative figure. My family and I would watch him organizing - doing the politics - from protests against the Indian Point Nuclear Power Station to cleaning up the Hudson River. These campaigns made his music even more powerful. He sang to get people involved in changing the world.

As I got a little older, growing up with interracial siblings, I began to see and feel the injustices I heard about in Pete Seeger's songs, and his lyrics carried even greater power for me. Listening to "Which Side Are You On" and other songs about the struggle for civil rights made me get active in middle school, when I was thirteen, organizing against racism with my friends.

And Pete's anti-war songs brought a realness to the conflicts supported by the United States Government in Central America during the 1980s, like the chilling "Crow on the Cradle" that sang that "somebody's baby is not coming back." That got me involved in solidarity work for Central America in my high school in my teens. Next it was organizing against Apartheid in South Africa while still in high school, and on and on over the years until Occupy Wall Street in New York, and now my partnerships with activists for housing rights and migrant organizing.

Pete Seeger's music is not in itself why I became political, but his lyrics and the way he sang and organized and conjured up a struggle, and represented in himself and his values and behavior the world he wanted to create outside, affected me very deeply. He was a key influence in my getting active, and absolutely central in keeping me in the struggle for social justice.

The inspiring and passionate music of that struggle, from "Union Maid" to "Talking Union," and even the lighter songs like "Bourgeois Blues" and "Little Boxes," all helped me to feel the possibilities of freedom on such a deep level. "We are not afraid ... we shall all be free" as Pete told us in We Shall Overcome.

I've never stopped listening to Pete Seeger, and now I play his songs for my baby too. Pete might have died in body, but he lives on in the power of his music.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

My mother was a civil rights and anti-war activist and my father was a GI who organized against the Vietnam War from inside the military. They met while organizing an anti-war Coffee House in Washington DC in 1969. I arrived on the scene two years later.

I grew up learning that everyone must seek justice - whatever that means to you - and it became an integral part of who I am. The music of Pete Seeger was central to that journey. My parents would listen to and sing his music all the time. My night time 'lullabies' were songs like "We Shall Overcome" (one of my mother's favorites) and "Kevin Barry" (one of my dad's).

Listening to these songs as a child I can remember being upset at their lyrics. "I Come and Stand at Every Door", Pete sang, but was the child in the song really a ghost? Where was Hiroshima, and how could children be allowed to die? Did all miners live in the conditions described in "Mrs. Clara Sullivan's Letter?" Why would "John Henry" have to die to "beat a machine." Pete also sang songs especially for children, which really made me think. I learned the meaning of being "ostracized" by listening to "Abiyoyo" before I was even in school, and took the lesson of that song to heart: even if you are counted as excluded, you can still beat giants.

Living in Croton-on-Hudson in upstate New York for much of my childhood, I was lucky enough to see Pete perform at the Clearwater Revival folk music celebrations he organized every year. I can remember his presence, so normal and accessible, and always trying to get everyone to participate. It was not about him, though he was the performer. It was his personality as much as his politics that made him such a transformative figure. My family and I would watch him organizing - doing the politics - from protests against the Indian Point Nuclear Power Station to cleaning up the Hudson River. These campaigns made his music even more powerful. He sang to get people involved in changing the world.

As I got a little older, growing up with interracial siblings, I began to see and feel the injustices I heard about in Pete Seeger's songs, and his lyrics carried even greater power for me. Listening to "Which Side Are You On" and other songs about the struggle for civil rights made me get active in middle school, when I was thirteen, organizing against racism with my friends.

And Pete's anti-war songs brought a realness to the conflicts supported by the United States Government in Central America during the 1980s, like the chilling "Crow on the Cradle" that sang that "somebody's baby is not coming back." That got me involved in solidarity work for Central America in my high school in my teens. Next it was organizing against Apartheid in South Africa while still in high school, and on and on over the years until Occupy Wall Street in New York, and now my partnerships with activists for housing rights and migrant organizing.

Pete Seeger's music is not in itself why I became political, but his lyrics and the way he sang and organized and conjured up a struggle, and represented in himself and his values and behavior the world he wanted to create outside, affected me very deeply. He was a key influence in my getting active, and absolutely central in keeping me in the struggle for social justice.

The inspiring and passionate music of that struggle, from "Union Maid" to "Talking Union," and even the lighter songs like "Bourgeois Blues" and "Little Boxes," all helped me to feel the possibilities of freedom on such a deep level. "We are not afraid ... we shall all be free" as Pete told us in We Shall Overcome.

I've never stopped listening to Pete Seeger, and now I play his songs for my baby too. Pete might have died in body, but he lives on in the power of his music.

My mother was a civil rights and anti-war activist and my father was a GI who organized against the Vietnam War from inside the military. They met while organizing an anti-war Coffee House in Washington DC in 1969. I arrived on the scene two years later.

I grew up learning that everyone must seek justice - whatever that means to you - and it became an integral part of who I am. The music of Pete Seeger was central to that journey. My parents would listen to and sing his music all the time. My night time 'lullabies' were songs like "We Shall Overcome" (one of my mother's favorites) and "Kevin Barry" (one of my dad's).

Listening to these songs as a child I can remember being upset at their lyrics. "I Come and Stand at Every Door", Pete sang, but was the child in the song really a ghost? Where was Hiroshima, and how could children be allowed to die? Did all miners live in the conditions described in "Mrs. Clara Sullivan's Letter?" Why would "John Henry" have to die to "beat a machine." Pete also sang songs especially for children, which really made me think. I learned the meaning of being "ostracized" by listening to "Abiyoyo" before I was even in school, and took the lesson of that song to heart: even if you are counted as excluded, you can still beat giants.

Living in Croton-on-Hudson in upstate New York for much of my childhood, I was lucky enough to see Pete perform at the Clearwater Revival folk music celebrations he organized every year. I can remember his presence, so normal and accessible, and always trying to get everyone to participate. It was not about him, though he was the performer. It was his personality as much as his politics that made him such a transformative figure. My family and I would watch him organizing - doing the politics - from protests against the Indian Point Nuclear Power Station to cleaning up the Hudson River. These campaigns made his music even more powerful. He sang to get people involved in changing the world.

As I got a little older, growing up with interracial siblings, I began to see and feel the injustices I heard about in Pete Seeger's songs, and his lyrics carried even greater power for me. Listening to "Which Side Are You On" and other songs about the struggle for civil rights made me get active in middle school, when I was thirteen, organizing against racism with my friends.

And Pete's anti-war songs brought a realness to the conflicts supported by the United States Government in Central America during the 1980s, like the chilling "Crow on the Cradle" that sang that "somebody's baby is not coming back." That got me involved in solidarity work for Central America in my high school in my teens. Next it was organizing against Apartheid in South Africa while still in high school, and on and on over the years until Occupy Wall Street in New York, and now my partnerships with activists for housing rights and migrant organizing.

Pete Seeger's music is not in itself why I became political, but his lyrics and the way he sang and organized and conjured up a struggle, and represented in himself and his values and behavior the world he wanted to create outside, affected me very deeply. He was a key influence in my getting active, and absolutely central in keeping me in the struggle for social justice.

The inspiring and passionate music of that struggle, from "Union Maid" to "Talking Union," and even the lighter songs like "Bourgeois Blues" and "Little Boxes," all helped me to feel the possibilities of freedom on such a deep level. "We are not afraid ... we shall all be free" as Pete told us in We Shall Overcome.

I've never stopped listening to Pete Seeger, and now I play his songs for my baby too. Pete might have died in body, but he lives on in the power of his music.