SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

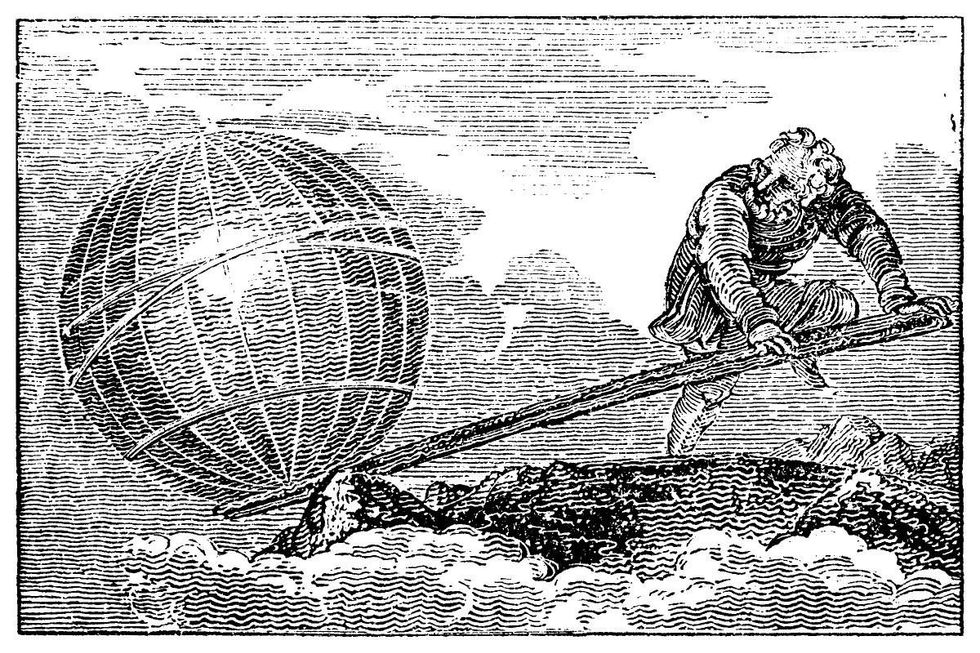

"Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world."

I think Archimedes was serious. I know we need to be. Now is the time to choose our future, as the Earth Charter declares. This means thinking big: embracing a vision so enormous it overflows our sense of the possible. For instance:

I think Archimedes was serious. I know we need to be. Now is the time to choose our future, as the Earth Charter declares. This means thinking big: embracing a vision so enormous it overflows our sense of the possible. For instance:

"Beginning with even just a small group united behind a shared vision of how to end war by dismantling the war machine, it will be possible to rally the global community to the vision of a future in which war is no longer something we accept." So Judith Hand wrote recently at the blog A Future Without War.

"I believe," she went on, "the world is actually yearning for such a movement to begin. I also believe that when it does, we will move amazingly swiftly to achieve a worldview shift of epic, stunning, historical magnitude."

Hand's essay is called "Dismantling the War Machine." It is not a topic she discusses hypothetically. She talks about it in the context of previous acts of stunning global leverage: the women's suffrage movement, Gandhi and the movement to end British colonial rule in India, the U.S. civil rights movement. She talks about it with a sense of what one might call looming, just out-of-reach inevitability.

That is, the time is excruciatingly right, the hell of the current system screams at us in daily headlines, most people want it -- but war is the way things are. Government serves it. The economy serves it. The media serve it. The system is sealed into place with a grim claim on reality. Visionaries who purport to look beyond it are nice people and utterly naive, or so the conventional thinking goes. But . . . enter Gandhi, King, Susan B. Anthony and so many others. Enter Archimedes.

Hand makes the point that nonviolent social movements apply the same physical principles the Greek mathematician elucidated 2,500 years ago -- and they work. The lever, she says, is "people power": the strategy and tactics of nonviolent action of all sorts. The fulcrum is any weak spot in the existing power structure, any shameful but unchallenged absurdity of power (e.g., segregated lunch counters, the British salt tax). The weight put on the lever to dislodge the fulcrum could, perhaps, be called applied moral authority.

The weight put on the lever to dislodge the fulcrum could, perhaps, be called applied moral authority.

"We intend to shift the ethos of our time," she writes, "from one that tolerates war to one that rejects war and by doing so, put an end to a behavior that has become dangerously obsolete and lay the foundation for a world that lives in peace."

This is the context in which I ponder what could easily be dismissed as an insignificant, ho-hum event, but which strikes me as potentially something else -- a bearing down on the global antiwar lever.

On June 6, the United Nations will convene a panel discussion examining nothing less than the abolition of war. Borrowing a phrase from the preamble of the U.N. Charter, the event is called: "Determined to Save Succeeding Generations from the Scourge of War."

Featured speakers include Jody Williams, chair of the Nobel Women's Initiative, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997 for her work to ban anti-personnel landmines; Paul Seger, Swiss ambassador to the United Nations; Nounou Booto Meeti, a Congolese journalist, human rights activist and program manager of the UK-based Centre for Peace, Security and Armed Violence Prevention; and Ralph Zacklin, former U.N. assistant-secretary-general for legal affairs.

I note all this with a sense of frustration bordering on desperation. The global war machine seems so enormous, so utterly in control of its own destiny -- at least until the Earth's resources give out and civilization collapses -- that anger, criticism, prayers and "pressure" from those who see its horror won't change anything. Additionally, I fear that institutions such as the United Nations, which have a significant global presence, exist only by permission of the rich and powerful, that they are tolerated and financially sustained only as long as their challenge to the war machine isn't serious. I fear that the global antiwar movement, lacking mainstream credibility, has no independent power capable of disrupting the war agenda.

Thus, even though millions of people around the planet took to the streets in protest against the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, the monstrous crime went forward on schedule. It wrecked a nation, killed, maimed and displaced untold millions of Iraqis, and eventually became an inconvenience to the American and British perpetrators, who then walked away from the mess they made. The Iraqis, as John Pilger recently reported, are left with a shattered society, a crippling sectarian war and swelling rates of cancer, birth defects and other diseases as a result of the lethal pollutants, including depleted uranium dust, the invaders left in their wake.

Surrendering to the inevitability of war is not the answer, however. As Hand and so many others point out, reality does shift, not merely on its own but as a result of determined minorities who learn how to use the lever of social action. A million small victories later, what they were fighting for -- what they gave body and soul for -- turns out to be common sense.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

I think Archimedes was serious. I know we need to be. Now is the time to choose our future, as the Earth Charter declares. This means thinking big: embracing a vision so enormous it overflows our sense of the possible. For instance:

"Beginning with even just a small group united behind a shared vision of how to end war by dismantling the war machine, it will be possible to rally the global community to the vision of a future in which war is no longer something we accept." So Judith Hand wrote recently at the blog A Future Without War.

"I believe," she went on, "the world is actually yearning for such a movement to begin. I also believe that when it does, we will move amazingly swiftly to achieve a worldview shift of epic, stunning, historical magnitude."

Hand's essay is called "Dismantling the War Machine." It is not a topic she discusses hypothetically. She talks about it in the context of previous acts of stunning global leverage: the women's suffrage movement, Gandhi and the movement to end British colonial rule in India, the U.S. civil rights movement. She talks about it with a sense of what one might call looming, just out-of-reach inevitability.

That is, the time is excruciatingly right, the hell of the current system screams at us in daily headlines, most people want it -- but war is the way things are. Government serves it. The economy serves it. The media serve it. The system is sealed into place with a grim claim on reality. Visionaries who purport to look beyond it are nice people and utterly naive, or so the conventional thinking goes. But . . . enter Gandhi, King, Susan B. Anthony and so many others. Enter Archimedes.

Hand makes the point that nonviolent social movements apply the same physical principles the Greek mathematician elucidated 2,500 years ago -- and they work. The lever, she says, is "people power": the strategy and tactics of nonviolent action of all sorts. The fulcrum is any weak spot in the existing power structure, any shameful but unchallenged absurdity of power (e.g., segregated lunch counters, the British salt tax). The weight put on the lever to dislodge the fulcrum could, perhaps, be called applied moral authority.

The weight put on the lever to dislodge the fulcrum could, perhaps, be called applied moral authority.

"We intend to shift the ethos of our time," she writes, "from one that tolerates war to one that rejects war and by doing so, put an end to a behavior that has become dangerously obsolete and lay the foundation for a world that lives in peace."

This is the context in which I ponder what could easily be dismissed as an insignificant, ho-hum event, but which strikes me as potentially something else -- a bearing down on the global antiwar lever.

On June 6, the United Nations will convene a panel discussion examining nothing less than the abolition of war. Borrowing a phrase from the preamble of the U.N. Charter, the event is called: "Determined to Save Succeeding Generations from the Scourge of War."

Featured speakers include Jody Williams, chair of the Nobel Women's Initiative, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997 for her work to ban anti-personnel landmines; Paul Seger, Swiss ambassador to the United Nations; Nounou Booto Meeti, a Congolese journalist, human rights activist and program manager of the UK-based Centre for Peace, Security and Armed Violence Prevention; and Ralph Zacklin, former U.N. assistant-secretary-general for legal affairs.

I note all this with a sense of frustration bordering on desperation. The global war machine seems so enormous, so utterly in control of its own destiny -- at least until the Earth's resources give out and civilization collapses -- that anger, criticism, prayers and "pressure" from those who see its horror won't change anything. Additionally, I fear that institutions such as the United Nations, which have a significant global presence, exist only by permission of the rich and powerful, that they are tolerated and financially sustained only as long as their challenge to the war machine isn't serious. I fear that the global antiwar movement, lacking mainstream credibility, has no independent power capable of disrupting the war agenda.

Thus, even though millions of people around the planet took to the streets in protest against the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, the monstrous crime went forward on schedule. It wrecked a nation, killed, maimed and displaced untold millions of Iraqis, and eventually became an inconvenience to the American and British perpetrators, who then walked away from the mess they made. The Iraqis, as John Pilger recently reported, are left with a shattered society, a crippling sectarian war and swelling rates of cancer, birth defects and other diseases as a result of the lethal pollutants, including depleted uranium dust, the invaders left in their wake.

Surrendering to the inevitability of war is not the answer, however. As Hand and so many others point out, reality does shift, not merely on its own but as a result of determined minorities who learn how to use the lever of social action. A million small victories later, what they were fighting for -- what they gave body and soul for -- turns out to be common sense.

I think Archimedes was serious. I know we need to be. Now is the time to choose our future, as the Earth Charter declares. This means thinking big: embracing a vision so enormous it overflows our sense of the possible. For instance:

"Beginning with even just a small group united behind a shared vision of how to end war by dismantling the war machine, it will be possible to rally the global community to the vision of a future in which war is no longer something we accept." So Judith Hand wrote recently at the blog A Future Without War.

"I believe," she went on, "the world is actually yearning for such a movement to begin. I also believe that when it does, we will move amazingly swiftly to achieve a worldview shift of epic, stunning, historical magnitude."

Hand's essay is called "Dismantling the War Machine." It is not a topic she discusses hypothetically. She talks about it in the context of previous acts of stunning global leverage: the women's suffrage movement, Gandhi and the movement to end British colonial rule in India, the U.S. civil rights movement. She talks about it with a sense of what one might call looming, just out-of-reach inevitability.

That is, the time is excruciatingly right, the hell of the current system screams at us in daily headlines, most people want it -- but war is the way things are. Government serves it. The economy serves it. The media serve it. The system is sealed into place with a grim claim on reality. Visionaries who purport to look beyond it are nice people and utterly naive, or so the conventional thinking goes. But . . . enter Gandhi, King, Susan B. Anthony and so many others. Enter Archimedes.

Hand makes the point that nonviolent social movements apply the same physical principles the Greek mathematician elucidated 2,500 years ago -- and they work. The lever, she says, is "people power": the strategy and tactics of nonviolent action of all sorts. The fulcrum is any weak spot in the existing power structure, any shameful but unchallenged absurdity of power (e.g., segregated lunch counters, the British salt tax). The weight put on the lever to dislodge the fulcrum could, perhaps, be called applied moral authority.

The weight put on the lever to dislodge the fulcrum could, perhaps, be called applied moral authority.

"We intend to shift the ethos of our time," she writes, "from one that tolerates war to one that rejects war and by doing so, put an end to a behavior that has become dangerously obsolete and lay the foundation for a world that lives in peace."

This is the context in which I ponder what could easily be dismissed as an insignificant, ho-hum event, but which strikes me as potentially something else -- a bearing down on the global antiwar lever.

On June 6, the United Nations will convene a panel discussion examining nothing less than the abolition of war. Borrowing a phrase from the preamble of the U.N. Charter, the event is called: "Determined to Save Succeeding Generations from the Scourge of War."

Featured speakers include Jody Williams, chair of the Nobel Women's Initiative, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997 for her work to ban anti-personnel landmines; Paul Seger, Swiss ambassador to the United Nations; Nounou Booto Meeti, a Congolese journalist, human rights activist and program manager of the UK-based Centre for Peace, Security and Armed Violence Prevention; and Ralph Zacklin, former U.N. assistant-secretary-general for legal affairs.

I note all this with a sense of frustration bordering on desperation. The global war machine seems so enormous, so utterly in control of its own destiny -- at least until the Earth's resources give out and civilization collapses -- that anger, criticism, prayers and "pressure" from those who see its horror won't change anything. Additionally, I fear that institutions such as the United Nations, which have a significant global presence, exist only by permission of the rich and powerful, that they are tolerated and financially sustained only as long as their challenge to the war machine isn't serious. I fear that the global antiwar movement, lacking mainstream credibility, has no independent power capable of disrupting the war agenda.

Thus, even though millions of people around the planet took to the streets in protest against the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, the monstrous crime went forward on schedule. It wrecked a nation, killed, maimed and displaced untold millions of Iraqis, and eventually became an inconvenience to the American and British perpetrators, who then walked away from the mess they made. The Iraqis, as John Pilger recently reported, are left with a shattered society, a crippling sectarian war and swelling rates of cancer, birth defects and other diseases as a result of the lethal pollutants, including depleted uranium dust, the invaders left in their wake.

Surrendering to the inevitability of war is not the answer, however. As Hand and so many others point out, reality does shift, not merely on its own but as a result of determined minorities who learn how to use the lever of social action. A million small victories later, what they were fighting for -- what they gave body and soul for -- turns out to be common sense.