We have to start somewhere.

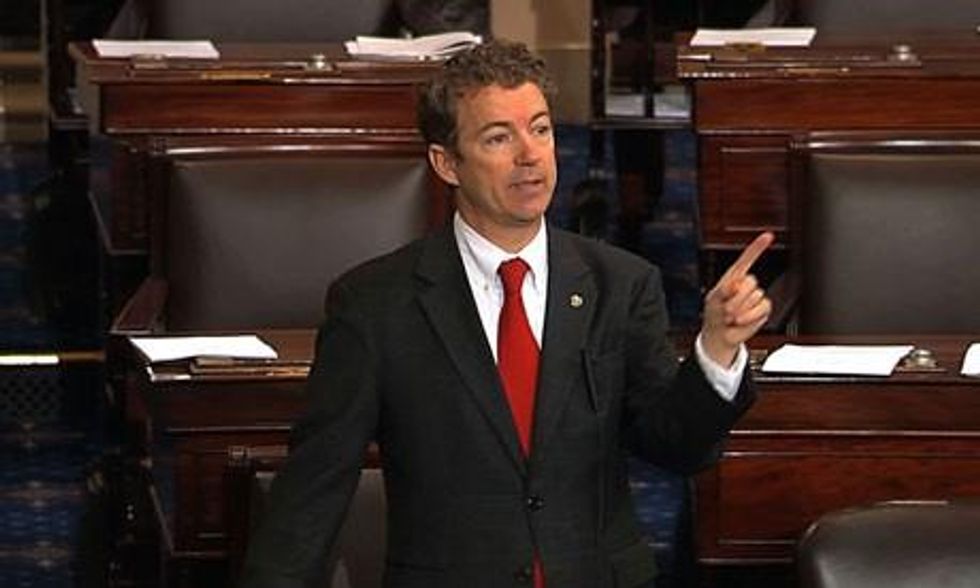

Senators Ted Cruz and Rand Paul have introduced a bill, S. 505, that would prohibit drone killings of U.S. citizens on U.S. soil if they do not represent an imminent threat. [The bill text is here, the link in Thomas, which doesn't have the bill text yet, is here.] Cruz and Paul have said that they want to attach their bill as an amendment to the continuing resolution which will fund the government through September.

If this bill becomes law, it would set an important precedent. It would be the first time since 2001 that Congress acted to limit the "war without boundaries" that was created by the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force after the 9/11 attacks. That would be a big deal, because getting any Congress to limit any Administration's warmaking in any way whatsoever is extremely difficult.

Some people will say: Rand Paul! Ted Cruz! I don't like them! I disagree with their position on something else.

But as I wrote last week: that's Washington. People who are with you on one thing are against you on something else. Ron Wyden has been a key champion on opening up the drone strike policy to public scrutiny. He's also an original co-sponsor of Lindsey Graham's bill that tries to pre-approve U.S. participation in an Israeli attack on Iran. Should I stay quiet about Ron Wyden's support for war with Iran because he's a key champion on drone strike scrutiny? Conversely, should I deny that he's been a key champion on drone strike scrutiny because I'm upset with him for pushing for war with Iran?

Arianna Huffington writes that Paul's filibuster "scrambled the ... right-vs.-left way of looking at the world," and that we need to keep the debate going, even if it's no longer on the Senate floor. Katrina vanden Heuvel, noting that the government is "waging a war on terrorism that admits no boundary and no end," reminds us that the national security apparatus termed Nelson Mandela a terrorist. We can't allow concerns about the Administration's lack of transparency about the drone strike policy to be dismissed on a partisan basis.

Some people will say: the government isn't conducting drone strikes in the U.S. There is no indication that the government plans to conduct drone strikes in the U.S. What is the point?

First: before embarking on big lectures about Senators pursuing hypothetical scenarios, people should check out Lindsey Graham's bill which tries to pre-approve U.S. military and diplomatic support for an Israeli attack on Iran. The New York Times has editorialized against this bill, on the grounds that Congress should leave President Obama alone to pursue talks with Iran. Americans for Peace Now has attacked the bill. But, as of this writing, 59 Senators have agreed to co-sponsor Graham's bill, because AIPAC told them to. If you are categorically opposed to your Senators taking a stand on hypothetical scenarios, you can tell your Senators not to sponsor the Graham/AIPAC bill here and here.

Second: Congress needs to establish a precedent that it can do something to re-assert its war powers. People complain about an imperial Presidency, but the necessary pre-condition of an imperial Presidency is a quiet Congress. The legal history is that courts will not intervene to protect Congressional war powers if Congress doesn't do anything to assert itself, regardless of what it says in the Constitution and the War Powers Resolution. In practice, courts have interpreted the Constitution's language on war powers to mean: the President has wide latitude to do things that Congress hasn't told him not to do. As a practical matter, if we don't want it to be legal for the President to do something, we need to get Congress to say that.

Third: codifying a Presidential policy into law is a standard tactic for Congress to try to constrain the President. During the Libya war, President Obama said he would not send U.S. ground troops to Libya. Good, said Representative John Conyers: let's put that into law. Introducing his amendment to prohibit the use of funds for ground troops - which passed overwhelmingly - Conyers said:

"My amendment is simply a common sense effort to codify the policy endorsed by President Obama and the international community and thereby ensure that our involvement in Libya remains limited in scope... The President has promised the American people that our military operations will not include ground troops. U.N. Resolution 1973 also states that military operations in Libya will exclude 'a foreign occupation force of any form on any part of Libyan territory.' In short, my amendment does not conflict with the President's policy- it would simply enact his promise into law."

Fourth: Congressional action generates political debate and media attention. For years progressive critics of the drone strike policy have been trying to raise issues that Senator Paul and Senator Cruz raised last week. There's a timeline of Congressional requests - Democratic and Republican - for the drone strike memos here.

The latest - a letter this week from leaders of the Congressional Progressive Caucus urging the President to make public an unclassified account of the drone strike memos and requesting a report to Congress on the policy - is here.

But our criticisms and concerns have been largely ignored by the Administration, because for the most part we haven't been able to get Democratic Members of Congress to strongly raise these criticisms and apply real pressure. Members of Congress wrote to the Administration, they complained, but until Senator Wyden and other Senators threatened to hold up John Brennan's nomination to head the CIA, these questions and complaints were ignored. It wasn't me who decided that it would be Rand Paul and Ted Cruz who would be the first to make a fuss about my concerns big enough to grab the attention of national media. I've been nagging Democratic Congressional offices for years: can we do something about the drone strikes? If it had been up to me, the concerns that were loudly raised by Senator Paul and Senator Cruz last week would have been loudly raised by Democratic Members of Congress years ago.

We are where we are. In raising a big stink about the drone strike policy, the civil liberties Republicans have gotten out in front of the civil liberties Democrats: the first to do a filibuster, the first to introduce legislation. When the battle is fully joined, it will be revealed that there's more concern about these issues on the Democratic side than there is on the Republican side. But to get the battle fully joined, we need to get more Members of Congress to speak up. And a key tool for getting Members of Congress to speak up is to have a bill that you can ask them to co-sponsor. We have to start somewhere. You can ask your Senators and Representative to speak up here.