SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

This past year saw the highly visible airing of concerns surrounding the Keystone XL (KXL) pipeline project. A broad group of citizens opposed KXL, citing the climate change impacts of extracting and transporting Canadian tar sands oil and the (not unlikely) possibility of a toxic tar sands oil spill over the environmentally sensitive Sand Hills region of Nebraska or above the Ogallala aquifer, a critical source of drinking water for the Great Plains.

In at least a temporary victory for this broad group of concerned citizens, President Obama punted Keystone's approval. Yet, tar sands oil remains a threat to communities and essential resources, not just along the proposed path of KXL, but in other parts of the country as well. There is reason to believe that New England is especially at risk.

Remember the 2010 Michigan oil spill? If that's not ringing a bell, here's a refresher: in July 2010, a pipeline operated by Enbridge Energy Partners -- the U.S. branch of Enbridge Inc., Canada's largest transporter of crude oil -- ruptured near Talmadge Creek, a tributary of Michigan's Kalamazoo River, spilling 1,148,413 gallons of tar sands oil. The National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB) attributed the spill to pipeline corrosion and "pervasive organizational failures." Further, NTSB suggested that Enbridge was aware that the section of the pipeline that ultimately burst was vulnerable, and failed to act on the information.

State and local officials were unprepared for what happened when the tar sands oil entered the river. The usual spill response methods -- applying skimmers and booms on the surface of the river -- were of little use because the heavy, viscous oil sank and spread along the bottom of the river. The spill contaminated some 36 miles of the Kalamazoo River, about 80 miles upstream from where the river empties into Lake Michigan. Fluids used to dilute the tar sands oil had become separated after the spill, meaning that toxic vapors containing benzene and polycyclic hydrocarbons escaped into the air, and thus the heavy oil sank.

According to a sample of Michigan residents, over one third of those living in impacted communities relocated due to local air pollution in the wake of the spill. Many were exposed to toxic vapors and reported troubling neurological, respiratory and gastrointestinal problems.

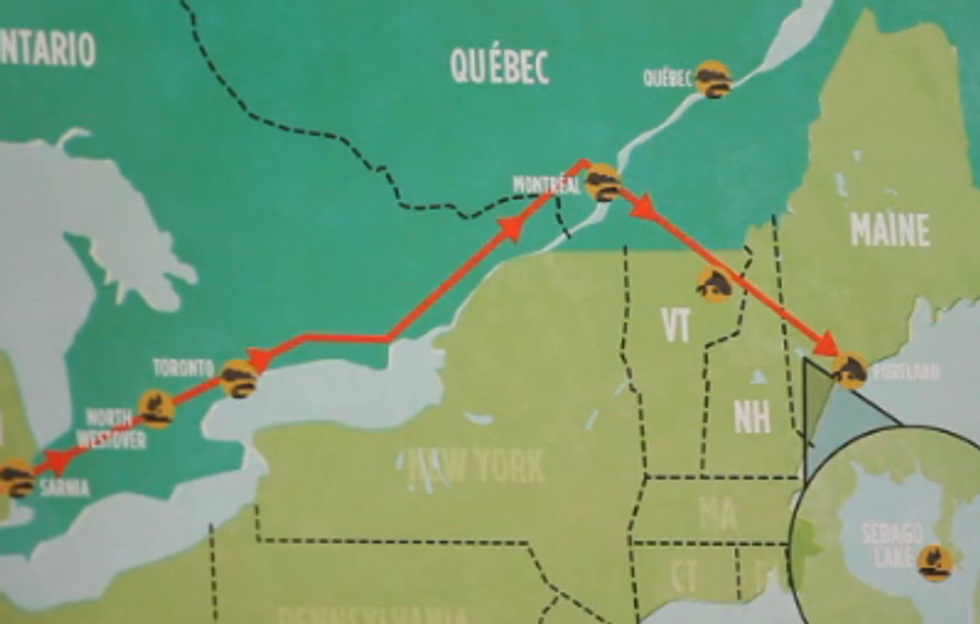

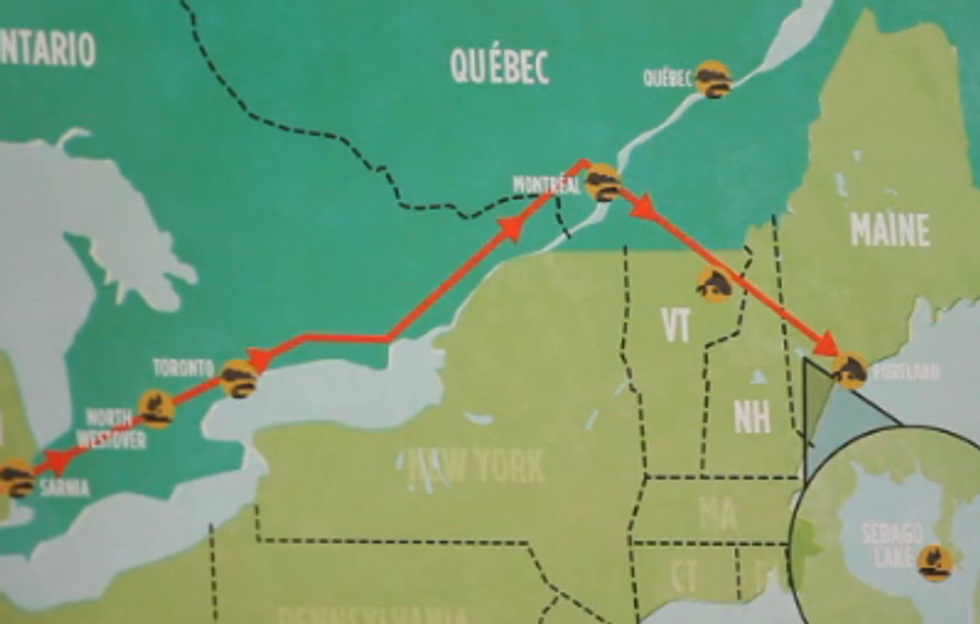

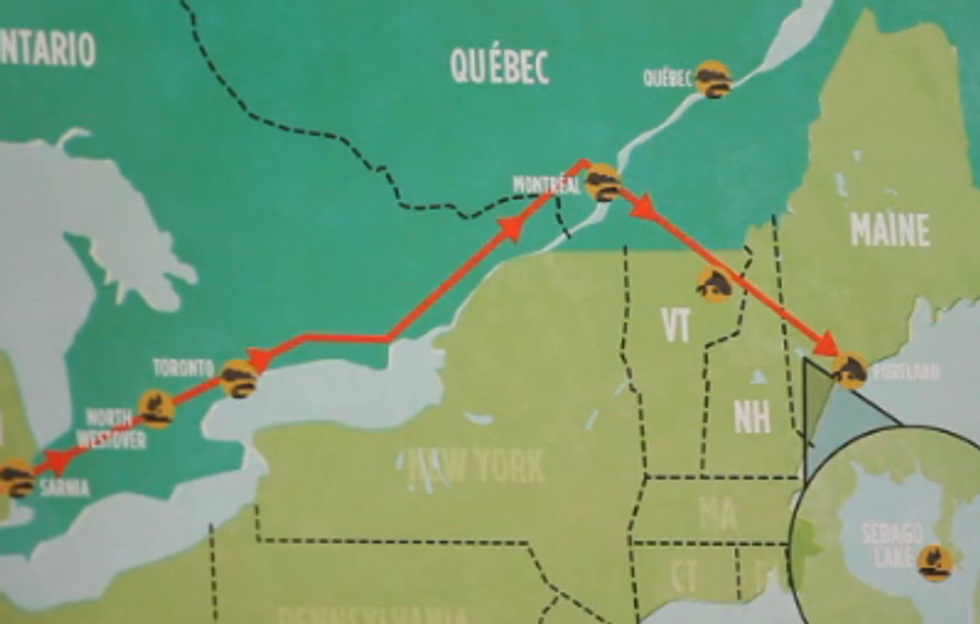

Now, the same company may have designs on New England. In 2008, there was buzz that the company was pursuing a "Trailbreaker" project that would have run Canadian tar sands oil through the aging Portland-Montreal pipeline, which stretches 236 miles across northern New England from Montreal, Canada to Portland, Maine.

Enbridge now claims it is no longer pursuing "Trailbreaker," but Enbridge is seeking permission to change the direction of flow -- from westbound to eastbound -- of a key section of its pipeline network, potentially to bring tar sands oil east. It seems that the company's piecemeal approach to bringing this dirtiest of oils east is tailored to avoid public outcry of the scale that has stalled KXL.

New England must be vigilant, and not allow this to happen. A tar sands oil spill along the path of the Portland-Montreal pipeline would be disastrous.

The pipeline crosses many of northern New England's major rivers including the Missisquoi, Black, Connecticut and Androscoggin. The aging pipeline also passes through the Crooked River watershed, the source of drinking water for one tenth of Maine's population and a major tributary of Sebago Lake, the source of Portland, Maine's drinking water. A threat of a spill of tar sands oil would also loom over New Hampshire's White Mountains, the Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge, renowned freshwater fisheries and countless other cherished places.

The risk is simply too great. Piping toxic tar sands through New England would be a bad deal for everyone but Enbridge.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

This past year saw the highly visible airing of concerns surrounding the Keystone XL (KXL) pipeline project. A broad group of citizens opposed KXL, citing the climate change impacts of extracting and transporting Canadian tar sands oil and the (not unlikely) possibility of a toxic tar sands oil spill over the environmentally sensitive Sand Hills region of Nebraska or above the Ogallala aquifer, a critical source of drinking water for the Great Plains.

In at least a temporary victory for this broad group of concerned citizens, President Obama punted Keystone's approval. Yet, tar sands oil remains a threat to communities and essential resources, not just along the proposed path of KXL, but in other parts of the country as well. There is reason to believe that New England is especially at risk.

Remember the 2010 Michigan oil spill? If that's not ringing a bell, here's a refresher: in July 2010, a pipeline operated by Enbridge Energy Partners -- the U.S. branch of Enbridge Inc., Canada's largest transporter of crude oil -- ruptured near Talmadge Creek, a tributary of Michigan's Kalamazoo River, spilling 1,148,413 gallons of tar sands oil. The National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB) attributed the spill to pipeline corrosion and "pervasive organizational failures." Further, NTSB suggested that Enbridge was aware that the section of the pipeline that ultimately burst was vulnerable, and failed to act on the information.

State and local officials were unprepared for what happened when the tar sands oil entered the river. The usual spill response methods -- applying skimmers and booms on the surface of the river -- were of little use because the heavy, viscous oil sank and spread along the bottom of the river. The spill contaminated some 36 miles of the Kalamazoo River, about 80 miles upstream from where the river empties into Lake Michigan. Fluids used to dilute the tar sands oil had become separated after the spill, meaning that toxic vapors containing benzene and polycyclic hydrocarbons escaped into the air, and thus the heavy oil sank.

According to a sample of Michigan residents, over one third of those living in impacted communities relocated due to local air pollution in the wake of the spill. Many were exposed to toxic vapors and reported troubling neurological, respiratory and gastrointestinal problems.

Now, the same company may have designs on New England. In 2008, there was buzz that the company was pursuing a "Trailbreaker" project that would have run Canadian tar sands oil through the aging Portland-Montreal pipeline, which stretches 236 miles across northern New England from Montreal, Canada to Portland, Maine.

Enbridge now claims it is no longer pursuing "Trailbreaker," but Enbridge is seeking permission to change the direction of flow -- from westbound to eastbound -- of a key section of its pipeline network, potentially to bring tar sands oil east. It seems that the company's piecemeal approach to bringing this dirtiest of oils east is tailored to avoid public outcry of the scale that has stalled KXL.

New England must be vigilant, and not allow this to happen. A tar sands oil spill along the path of the Portland-Montreal pipeline would be disastrous.

The pipeline crosses many of northern New England's major rivers including the Missisquoi, Black, Connecticut and Androscoggin. The aging pipeline also passes through the Crooked River watershed, the source of drinking water for one tenth of Maine's population and a major tributary of Sebago Lake, the source of Portland, Maine's drinking water. A threat of a spill of tar sands oil would also loom over New Hampshire's White Mountains, the Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge, renowned freshwater fisheries and countless other cherished places.

The risk is simply too great. Piping toxic tar sands through New England would be a bad deal for everyone but Enbridge.

This past year saw the highly visible airing of concerns surrounding the Keystone XL (KXL) pipeline project. A broad group of citizens opposed KXL, citing the climate change impacts of extracting and transporting Canadian tar sands oil and the (not unlikely) possibility of a toxic tar sands oil spill over the environmentally sensitive Sand Hills region of Nebraska or above the Ogallala aquifer, a critical source of drinking water for the Great Plains.

In at least a temporary victory for this broad group of concerned citizens, President Obama punted Keystone's approval. Yet, tar sands oil remains a threat to communities and essential resources, not just along the proposed path of KXL, but in other parts of the country as well. There is reason to believe that New England is especially at risk.

Remember the 2010 Michigan oil spill? If that's not ringing a bell, here's a refresher: in July 2010, a pipeline operated by Enbridge Energy Partners -- the U.S. branch of Enbridge Inc., Canada's largest transporter of crude oil -- ruptured near Talmadge Creek, a tributary of Michigan's Kalamazoo River, spilling 1,148,413 gallons of tar sands oil. The National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB) attributed the spill to pipeline corrosion and "pervasive organizational failures." Further, NTSB suggested that Enbridge was aware that the section of the pipeline that ultimately burst was vulnerable, and failed to act on the information.

State and local officials were unprepared for what happened when the tar sands oil entered the river. The usual spill response methods -- applying skimmers and booms on the surface of the river -- were of little use because the heavy, viscous oil sank and spread along the bottom of the river. The spill contaminated some 36 miles of the Kalamazoo River, about 80 miles upstream from where the river empties into Lake Michigan. Fluids used to dilute the tar sands oil had become separated after the spill, meaning that toxic vapors containing benzene and polycyclic hydrocarbons escaped into the air, and thus the heavy oil sank.

According to a sample of Michigan residents, over one third of those living in impacted communities relocated due to local air pollution in the wake of the spill. Many were exposed to toxic vapors and reported troubling neurological, respiratory and gastrointestinal problems.

Now, the same company may have designs on New England. In 2008, there was buzz that the company was pursuing a "Trailbreaker" project that would have run Canadian tar sands oil through the aging Portland-Montreal pipeline, which stretches 236 miles across northern New England from Montreal, Canada to Portland, Maine.

Enbridge now claims it is no longer pursuing "Trailbreaker," but Enbridge is seeking permission to change the direction of flow -- from westbound to eastbound -- of a key section of its pipeline network, potentially to bring tar sands oil east. It seems that the company's piecemeal approach to bringing this dirtiest of oils east is tailored to avoid public outcry of the scale that has stalled KXL.

New England must be vigilant, and not allow this to happen. A tar sands oil spill along the path of the Portland-Montreal pipeline would be disastrous.

The pipeline crosses many of northern New England's major rivers including the Missisquoi, Black, Connecticut and Androscoggin. The aging pipeline also passes through the Crooked River watershed, the source of drinking water for one tenth of Maine's population and a major tributary of Sebago Lake, the source of Portland, Maine's drinking water. A threat of a spill of tar sands oil would also loom over New Hampshire's White Mountains, the Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge, renowned freshwater fisheries and countless other cherished places.

The risk is simply too great. Piping toxic tar sands through New England would be a bad deal for everyone but Enbridge.