Mitt Romney's 20th-Century Worldview

Like a caveman frozen in a glacier, Mitt Romney is a man trapped in time -- from his archaic stance on women's rights to his belief in Herbert Hoover economics.

Like a caveman frozen in a glacier, Mitt Romney is a man trapped in time -- from his archaic stance on women's rights to his belief in Herbert Hoover economics.

And now it appears his foreign policy is stuck in the past, as well.

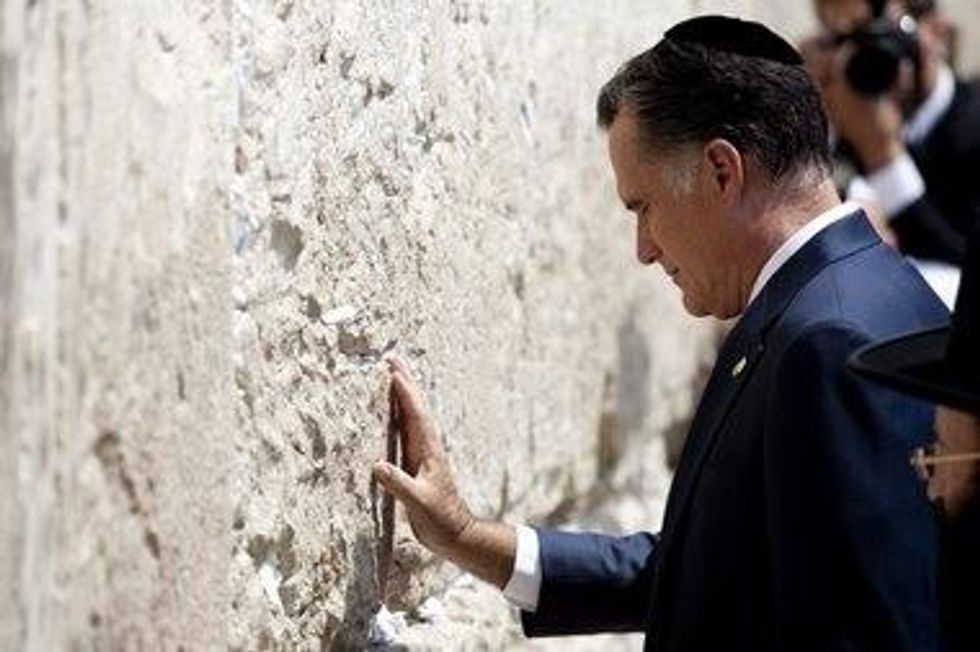

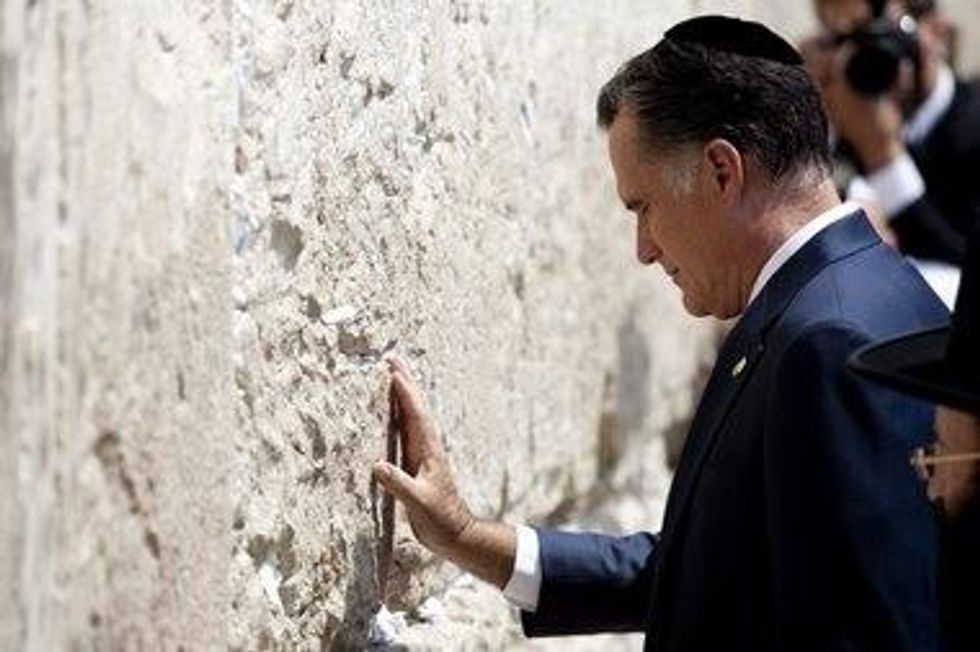

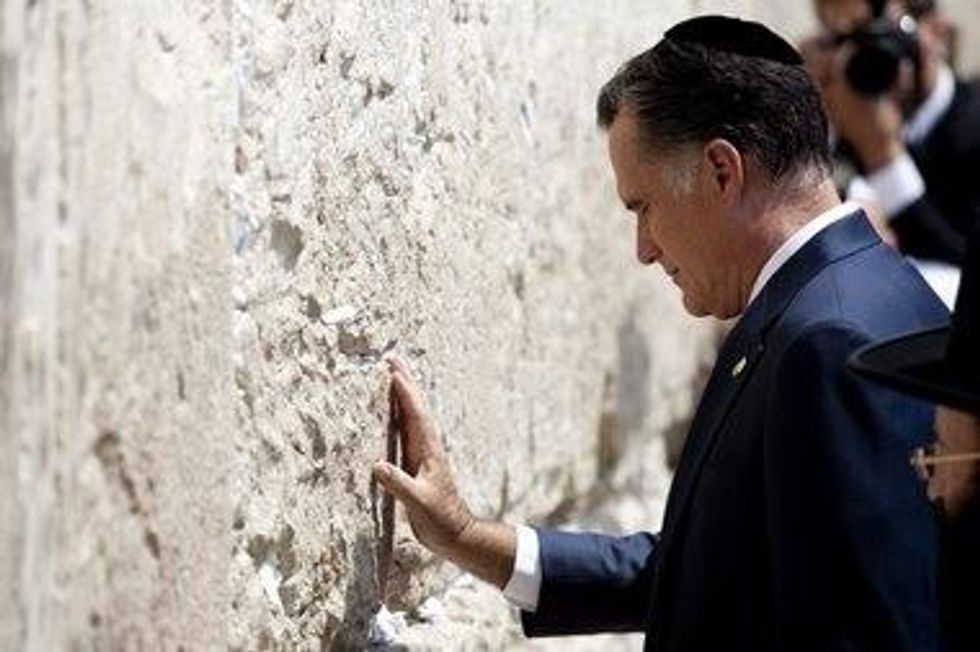

This week, Romney is on a six-day, three-nation tour. The trip comes days after he promised in a speech on international affairs to usher in another "American century."

What does Romney's American century look like? His speech and his itinerary tell us volumes.

Romney's world is one of special relationships, particularly with Britain, Israel and Poland -- the three nations he's visiting. It's also a world of special enmities -- against Iran -- and unending suspicions -- about China and Russia. For Romney, there are three types of countries: countries that are with us; countries that are against us; and countries that will be against us, sooner or later.

If this seems like foreign policy out of a 20th-century history book -- or the George W. Bush neocon playbook -- that's because it is. A President Romney wouldn't bring about "another American century." Rather, he would return us to some of the worst policies of the last century.

His worldview recalls the early Reagan years, before the Gipper and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev found common ground on nuclear disarmament -- and long before Secretary of State James Baker steered President George H.W. Bush and the country away from a special relationship with Israel that required the United States to take on all of Israel's enemies. It was in those reckless first years in which Reagan's policies brought the world close to a nuclear confrontation and led U.S. forces into the deadly trap of confrontation with Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Romney's foreign policy smacks of the same recklessness -- a belief that being strong means throwing your weight around. Will his embrace of the special relationship with Israel and Reagan-era bravado lead to equally dangerous developments?

Romney's world also reminds us of the early Bush 43 years, with its mix of paranoia, arrogance and belief in U.S. power that gave us the "axis of evil" and the Iraq war. Remember, it was America's special friends, Britain and Poland, that headed the list of Bush's "coalition of the willing" and gave a veneer of international support for that catastrophe. For Romney, the villain is Iran. Will we once again be neo-conned into a disastrous war in the Persian Gulf?

Romney may accuse President Obama of carrying out defeatist policies and accepting American decline. But it is the GOP nominee-to-be and his advisers whose perspective and policies are much too small -- and far too backwards -- for a 21st-century United States.

Romney's speech and his trip reveal, in fact, that he has no answers to the critical foreign-policy questions -- the questions that will shape the world order, and America's place in it, in the coming decade:

How to prevent a country like Syria from plunging into an even bloodier sectarian war while keeping the hope of democracy and economic development alive?

How can the United States work with the current world powers -- and the rising ones such as Russia, China, Brazil and India -- to establish a form of international governance that balances respect for human dignity with respect for international order?

How can the United States engage these countries in dealing with the transnational threats -- from mass unemployment to global climate change -- that are likely to define the next decade?

And how can the president bring together leading nations to stop the slide toward a new Great Depression?

It is not even clear that Romney knows what these questions are.

Obama, for better or worse, does understand these key questions. To be sure, he has made some patently wrong decisions, such as the escalation of drone warfare, his secret counterterrorism programs and his embrace of growing state secrecy. But the fact that the president has ended one war -- Iraq -- and started to end another -- Afghanistan -- is an opportunity to move to a new foreign-policy stance, a new internationalism.

This means rejecting the tendency to measure our nation's strength by our capacity to destroy -- in bullets and body counts and payloads. The real test of our nation's standing lies in our capacity to build -- not just schools and hospitals and bridges but also relationships across rivers and among countries. Indeed, a new internationalism calls not for military adventures, bombs and bases but for international, collective efforts on the issues that truly matter today -- eliminating nuclear weapons, rolling back climate change and advancing the health, education, prosperity and human rights of all people.

It has taken four years to wind down the costly wars of occupation of the Bush era. It would be a tragedy to let Romney and his neocon advisers take us back to the failed policies of the past.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Like a caveman frozen in a glacier, Mitt Romney is a man trapped in time -- from his archaic stance on women's rights to his belief in Herbert Hoover economics.

And now it appears his foreign policy is stuck in the past, as well.

This week, Romney is on a six-day, three-nation tour. The trip comes days after he promised in a speech on international affairs to usher in another "American century."

What does Romney's American century look like? His speech and his itinerary tell us volumes.

Romney's world is one of special relationships, particularly with Britain, Israel and Poland -- the three nations he's visiting. It's also a world of special enmities -- against Iran -- and unending suspicions -- about China and Russia. For Romney, there are three types of countries: countries that are with us; countries that are against us; and countries that will be against us, sooner or later.

If this seems like foreign policy out of a 20th-century history book -- or the George W. Bush neocon playbook -- that's because it is. A President Romney wouldn't bring about "another American century." Rather, he would return us to some of the worst policies of the last century.

His worldview recalls the early Reagan years, before the Gipper and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev found common ground on nuclear disarmament -- and long before Secretary of State James Baker steered President George H.W. Bush and the country away from a special relationship with Israel that required the United States to take on all of Israel's enemies. It was in those reckless first years in which Reagan's policies brought the world close to a nuclear confrontation and led U.S. forces into the deadly trap of confrontation with Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Romney's foreign policy smacks of the same recklessness -- a belief that being strong means throwing your weight around. Will his embrace of the special relationship with Israel and Reagan-era bravado lead to equally dangerous developments?

Romney's world also reminds us of the early Bush 43 years, with its mix of paranoia, arrogance and belief in U.S. power that gave us the "axis of evil" and the Iraq war. Remember, it was America's special friends, Britain and Poland, that headed the list of Bush's "coalition of the willing" and gave a veneer of international support for that catastrophe. For Romney, the villain is Iran. Will we once again be neo-conned into a disastrous war in the Persian Gulf?

Romney may accuse President Obama of carrying out defeatist policies and accepting American decline. But it is the GOP nominee-to-be and his advisers whose perspective and policies are much too small -- and far too backwards -- for a 21st-century United States.

Romney's speech and his trip reveal, in fact, that he has no answers to the critical foreign-policy questions -- the questions that will shape the world order, and America's place in it, in the coming decade:

How to prevent a country like Syria from plunging into an even bloodier sectarian war while keeping the hope of democracy and economic development alive?

How can the United States work with the current world powers -- and the rising ones such as Russia, China, Brazil and India -- to establish a form of international governance that balances respect for human dignity with respect for international order?

How can the United States engage these countries in dealing with the transnational threats -- from mass unemployment to global climate change -- that are likely to define the next decade?

And how can the president bring together leading nations to stop the slide toward a new Great Depression?

It is not even clear that Romney knows what these questions are.

Obama, for better or worse, does understand these key questions. To be sure, he has made some patently wrong decisions, such as the escalation of drone warfare, his secret counterterrorism programs and his embrace of growing state secrecy. But the fact that the president has ended one war -- Iraq -- and started to end another -- Afghanistan -- is an opportunity to move to a new foreign-policy stance, a new internationalism.

This means rejecting the tendency to measure our nation's strength by our capacity to destroy -- in bullets and body counts and payloads. The real test of our nation's standing lies in our capacity to build -- not just schools and hospitals and bridges but also relationships across rivers and among countries. Indeed, a new internationalism calls not for military adventures, bombs and bases but for international, collective efforts on the issues that truly matter today -- eliminating nuclear weapons, rolling back climate change and advancing the health, education, prosperity and human rights of all people.

It has taken four years to wind down the costly wars of occupation of the Bush era. It would be a tragedy to let Romney and his neocon advisers take us back to the failed policies of the past.

Like a caveman frozen in a glacier, Mitt Romney is a man trapped in time -- from his archaic stance on women's rights to his belief in Herbert Hoover economics.

And now it appears his foreign policy is stuck in the past, as well.

This week, Romney is on a six-day, three-nation tour. The trip comes days after he promised in a speech on international affairs to usher in another "American century."

What does Romney's American century look like? His speech and his itinerary tell us volumes.

Romney's world is one of special relationships, particularly with Britain, Israel and Poland -- the three nations he's visiting. It's also a world of special enmities -- against Iran -- and unending suspicions -- about China and Russia. For Romney, there are three types of countries: countries that are with us; countries that are against us; and countries that will be against us, sooner or later.

If this seems like foreign policy out of a 20th-century history book -- or the George W. Bush neocon playbook -- that's because it is. A President Romney wouldn't bring about "another American century." Rather, he would return us to some of the worst policies of the last century.

His worldview recalls the early Reagan years, before the Gipper and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev found common ground on nuclear disarmament -- and long before Secretary of State James Baker steered President George H.W. Bush and the country away from a special relationship with Israel that required the United States to take on all of Israel's enemies. It was in those reckless first years in which Reagan's policies brought the world close to a nuclear confrontation and led U.S. forces into the deadly trap of confrontation with Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Romney's foreign policy smacks of the same recklessness -- a belief that being strong means throwing your weight around. Will his embrace of the special relationship with Israel and Reagan-era bravado lead to equally dangerous developments?

Romney's world also reminds us of the early Bush 43 years, with its mix of paranoia, arrogance and belief in U.S. power that gave us the "axis of evil" and the Iraq war. Remember, it was America's special friends, Britain and Poland, that headed the list of Bush's "coalition of the willing" and gave a veneer of international support for that catastrophe. For Romney, the villain is Iran. Will we once again be neo-conned into a disastrous war in the Persian Gulf?

Romney may accuse President Obama of carrying out defeatist policies and accepting American decline. But it is the GOP nominee-to-be and his advisers whose perspective and policies are much too small -- and far too backwards -- for a 21st-century United States.

Romney's speech and his trip reveal, in fact, that he has no answers to the critical foreign-policy questions -- the questions that will shape the world order, and America's place in it, in the coming decade:

How to prevent a country like Syria from plunging into an even bloodier sectarian war while keeping the hope of democracy and economic development alive?

How can the United States work with the current world powers -- and the rising ones such as Russia, China, Brazil and India -- to establish a form of international governance that balances respect for human dignity with respect for international order?

How can the United States engage these countries in dealing with the transnational threats -- from mass unemployment to global climate change -- that are likely to define the next decade?

And how can the president bring together leading nations to stop the slide toward a new Great Depression?

It is not even clear that Romney knows what these questions are.

Obama, for better or worse, does understand these key questions. To be sure, he has made some patently wrong decisions, such as the escalation of drone warfare, his secret counterterrorism programs and his embrace of growing state secrecy. But the fact that the president has ended one war -- Iraq -- and started to end another -- Afghanistan -- is an opportunity to move to a new foreign-policy stance, a new internationalism.

This means rejecting the tendency to measure our nation's strength by our capacity to destroy -- in bullets and body counts and payloads. The real test of our nation's standing lies in our capacity to build -- not just schools and hospitals and bridges but also relationships across rivers and among countries. Indeed, a new internationalism calls not for military adventures, bombs and bases but for international, collective efforts on the issues that truly matter today -- eliminating nuclear weapons, rolling back climate change and advancing the health, education, prosperity and human rights of all people.

It has taken four years to wind down the costly wars of occupation of the Bush era. It would be a tragedy to let Romney and his neocon advisers take us back to the failed policies of the past.