If the Cords of Culture are Cut, How Will We Access the Potential Sources of Our Renewal?

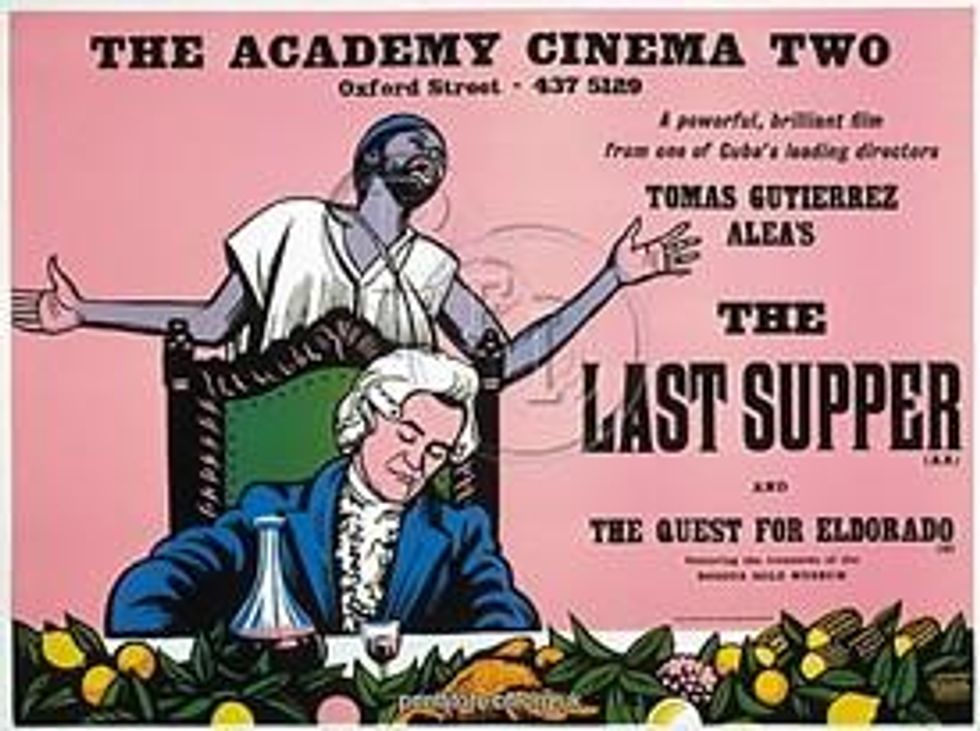

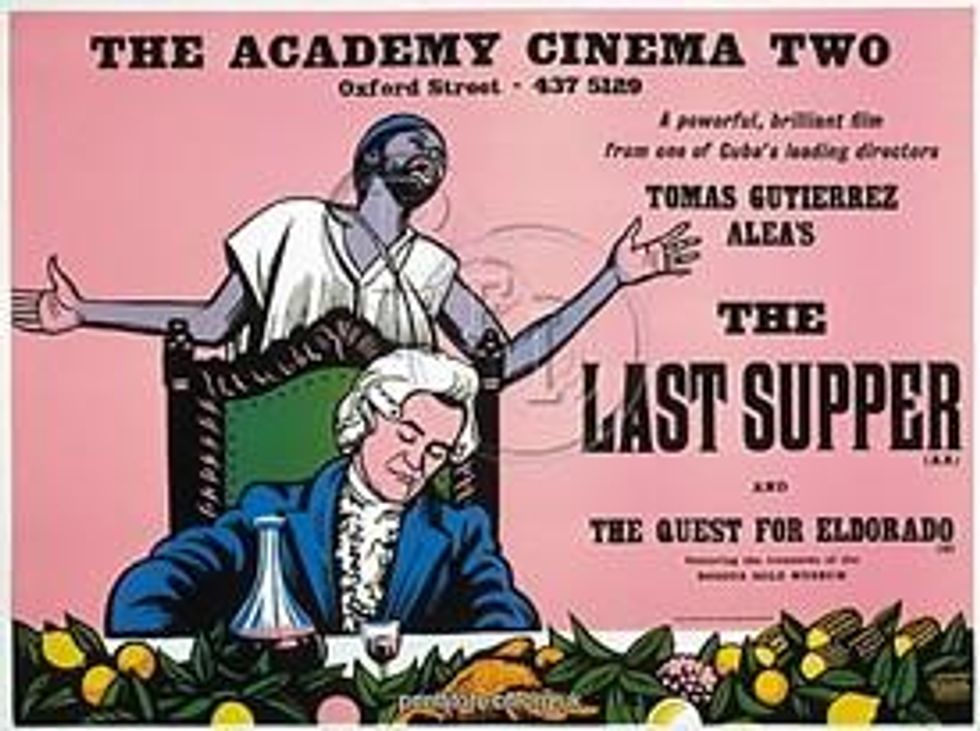

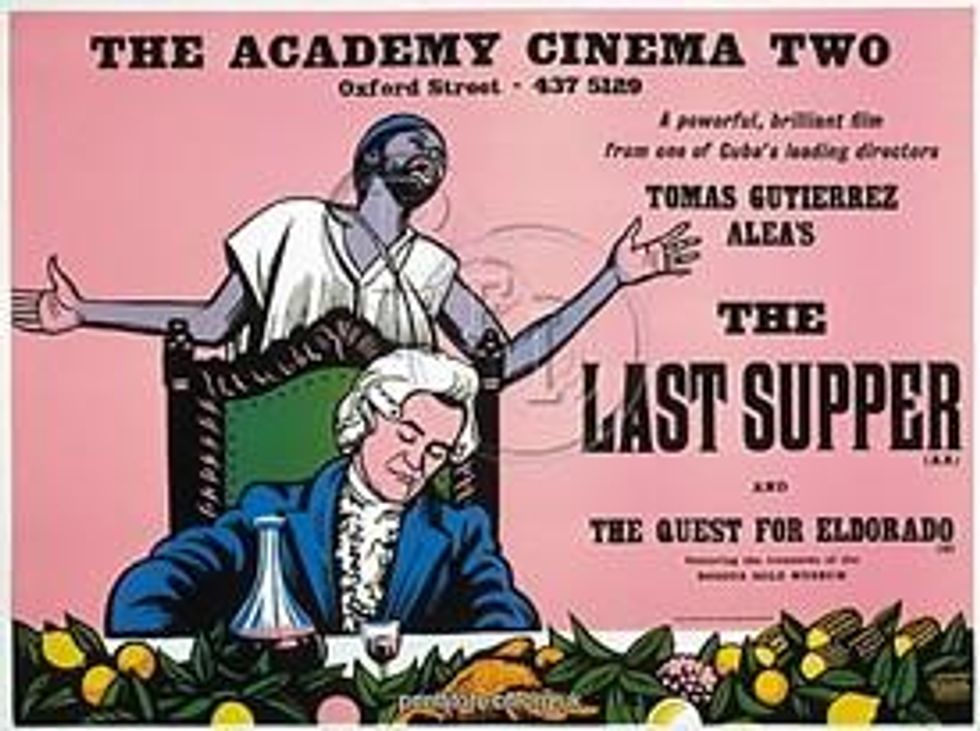

This past week, I had the pleasure of teaching the Last Supper, Tomas Gutierrez Alea's 1976 masterpiece, to a group of very bright and conscientious undergraduate students.

This past week, I had the pleasure of teaching the Last Supper, Tomas Gutierrez Alea's 1976 masterpiece, to a group of very bright and conscientious undergraduate students.

The film is set on a Cuban sugar plantation in the waning years of the eighteenth century and tells the story of how the owner the place, a Spanish Count who has developed a certain penchant for the liberal ideals then circulating in the court of Spain's "enlightened despot", Carlos III, decides to democratize the traditional celebration of Holy Week at his Caribbean property.

Just as a true appreciation of Stephen Colbert depends on having seen a real conservative blowhard in action, a real understanding the Cuban film depends on having at least a skeletal understanding of the iconic importance of the Last Supper within Christian life, and from there, the entire trajectory of Western Culture.

We can agree or disagree on the wisdom and/or the efficacy of the lessons contained in the event which, we are told, took place in an upper chamber of a building in Jerusalem some two thousand years ago. What we cannot do and be honest with ourselves is to deny its absolutely central importance to the making of our received cultural inheritance.

To take just one of virtually thousands of examples that could be adduced, there can be no real comprehension of what drove Martin Luther King's doctrine of non-violence without an understanding of the importance in his life, and that of millions of other Americans (both black and white), of that Holy Thursday narrative of extreme self-sacrifice.

I have probably taught the Last Supper 5 or 6 times over the last eighteen years. During that time, I have, I think, become fairly aware of some of the challenges it presents to North American students. One is its Cuban provenance. Some students have trouble getting beyond the fact that it is a film imported from what they know to be a "bad" Communist country.

Another is its relatively slow narrative rhythm. Though we don't often talk about it, the insertion into the mainstream of US cinematic practices some time in the nineties of the of frequent, quick and jarring visual cuts developed originally in the advertising and music video industries has fundamentally altered the narrative expectations of young viewers. If the film does not move along in what they consider to be a "normal" temporal cadence, they have a certain tendency to simply tune it out.

I have found, however, that if I address these issues in a straightforward manner at the beginning of our analysis, students can often burrow quite deeply into the film, eventually coming to appreciate its superb construction and challenging messages.

This last time, however, I encountered a challenge that had never before presented itself: a clear majority of the students were largely unfamiliar with the basic narrative of what is said to have gone on at that first Last Supper two millennia ago.

And that got me thinking, among other things, about the issue of cultural transmission in our day.

I would like to make clear that my intention here is not to bash my students. These are sharp young people possessing lots of curiosity and general levels of personal aplomb and directedness that I could not have dreamed of having at their age. They have spent their lives in the midst of a revolution of information availability that has few, if any, parallels in the history of the world. In such unsettled times, is to be expected that many previously "indispensable" facts get shunted aside or simply forgotten.

But my ability empathize with my student's situation in this new information environment does not, I must admit, allay my nervousness about what it portends for those of us that seek to engender the creation a more just and humane world.

Though we--especially those of us that live here in the linearly-minded West of the West--most frequently use vocabulary associated the processes of "birth" and "invention" to describe great cultural and political changes, these metaphors are not terribly apt.

Much more accurate, in my view, would be to speak in terms of alchemy and recombinance. Most great leaps forward in social consciousness have come about not as the result of the generation of wholly new ideas, but rather through the creative redeployment and repurposing of old ones.

When the prosperous merchant class of late medieval Italy wanted to show the world its vital energy, it mined the toolbox of the Greek and Roman classics. The result was what we now call the Renaissance. When, starting a hundred and fifty years ago, the Catalan bourgeoisie wanted to demonstrate its modernity, and with it, its differentness from its counterparts in the rest of Spain, it delved--selectively as had northern Italians done with the Greeks and Romans-- into its own storied medieval past. The result, among many other things, was the stunning modernista architecture that now makes Barcelona one of the world's great tourist destinations.

The same rules apply in politics. When seeking to convince a skeptical populace of the legitimacy of his brutal dictatorship (1939-1975), Francisco Franco borrowed liberally from the iconography of Spain's Golden Age (1500-1650).

Closer to us in both geography and time, Ronald Reagan appropriated the imagery of the supposed good times under Coolidge and Eisenhower to legitimate his regime of social destruction. And since that time, every Republican candidate for office has, in turn, presented the recuperation of the supposed good times under Reagan the prime goal of his or her run of "public service".

Meanwhile, the US left (or what passes for it) has resolutely refused to dig into the treasure trove of its rich past in their efforts to mobilize the populace. Indeed, the man who sits in the White House has, to my knowledge, has only spoken openly of having one hero from this country's contemporary past.

Who was it? Ronald Reagan - the patron saint of all those that hurl hate and misinformation against him in today's political environment.

An entire archive of the left's role in generating the great American middle class is dying before our eyes, not because, as is so often repeated, it has no natural constituency, but because its nominal custodians refuse to mount even the most feeble defense of the values contained therein.

In politics, if a body of values and ideas lies untouched for more than two generations, it generally dies. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say, that for most of my generation and all that of my students the idea that insuring dignity, and freedom from unnecessary privation, can and should be the organizing principle of society, has virtually no palpable presence in their lives.

To build anew is noble and necessary. But as studies of trans-generational poverty demonstrate, doing so is infinitely more difficult when privation has been one's only norm.

The same is true in culture and politics. Recent studies in cognitive science increasingly suggest that we can only truly conceptualize the things for which we have an available vocabulary.

I think we all are hoping desperately for some form of social and political renewal. But can we really expect it when, to paraphrase Milton Friedman, the only "ideas lying around" in considerable quantities within our public space belong to the other side?

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

This past week, I had the pleasure of teaching the Last Supper, Tomas Gutierrez Alea's 1976 masterpiece, to a group of very bright and conscientious undergraduate students.

The film is set on a Cuban sugar plantation in the waning years of the eighteenth century and tells the story of how the owner the place, a Spanish Count who has developed a certain penchant for the liberal ideals then circulating in the court of Spain's "enlightened despot", Carlos III, decides to democratize the traditional celebration of Holy Week at his Caribbean property.

Just as a true appreciation of Stephen Colbert depends on having seen a real conservative blowhard in action, a real understanding the Cuban film depends on having at least a skeletal understanding of the iconic importance of the Last Supper within Christian life, and from there, the entire trajectory of Western Culture.

We can agree or disagree on the wisdom and/or the efficacy of the lessons contained in the event which, we are told, took place in an upper chamber of a building in Jerusalem some two thousand years ago. What we cannot do and be honest with ourselves is to deny its absolutely central importance to the making of our received cultural inheritance.

To take just one of virtually thousands of examples that could be adduced, there can be no real comprehension of what drove Martin Luther King's doctrine of non-violence without an understanding of the importance in his life, and that of millions of other Americans (both black and white), of that Holy Thursday narrative of extreme self-sacrifice.

I have probably taught the Last Supper 5 or 6 times over the last eighteen years. During that time, I have, I think, become fairly aware of some of the challenges it presents to North American students. One is its Cuban provenance. Some students have trouble getting beyond the fact that it is a film imported from what they know to be a "bad" Communist country.

Another is its relatively slow narrative rhythm. Though we don't often talk about it, the insertion into the mainstream of US cinematic practices some time in the nineties of the of frequent, quick and jarring visual cuts developed originally in the advertising and music video industries has fundamentally altered the narrative expectations of young viewers. If the film does not move along in what they consider to be a "normal" temporal cadence, they have a certain tendency to simply tune it out.

I have found, however, that if I address these issues in a straightforward manner at the beginning of our analysis, students can often burrow quite deeply into the film, eventually coming to appreciate its superb construction and challenging messages.

This last time, however, I encountered a challenge that had never before presented itself: a clear majority of the students were largely unfamiliar with the basic narrative of what is said to have gone on at that first Last Supper two millennia ago.

And that got me thinking, among other things, about the issue of cultural transmission in our day.

I would like to make clear that my intention here is not to bash my students. These are sharp young people possessing lots of curiosity and general levels of personal aplomb and directedness that I could not have dreamed of having at their age. They have spent their lives in the midst of a revolution of information availability that has few, if any, parallels in the history of the world. In such unsettled times, is to be expected that many previously "indispensable" facts get shunted aside or simply forgotten.

But my ability empathize with my student's situation in this new information environment does not, I must admit, allay my nervousness about what it portends for those of us that seek to engender the creation a more just and humane world.

Though we--especially those of us that live here in the linearly-minded West of the West--most frequently use vocabulary associated the processes of "birth" and "invention" to describe great cultural and political changes, these metaphors are not terribly apt.

Much more accurate, in my view, would be to speak in terms of alchemy and recombinance. Most great leaps forward in social consciousness have come about not as the result of the generation of wholly new ideas, but rather through the creative redeployment and repurposing of old ones.

When the prosperous merchant class of late medieval Italy wanted to show the world its vital energy, it mined the toolbox of the Greek and Roman classics. The result was what we now call the Renaissance. When, starting a hundred and fifty years ago, the Catalan bourgeoisie wanted to demonstrate its modernity, and with it, its differentness from its counterparts in the rest of Spain, it delved--selectively as had northern Italians done with the Greeks and Romans-- into its own storied medieval past. The result, among many other things, was the stunning modernista architecture that now makes Barcelona one of the world's great tourist destinations.

The same rules apply in politics. When seeking to convince a skeptical populace of the legitimacy of his brutal dictatorship (1939-1975), Francisco Franco borrowed liberally from the iconography of Spain's Golden Age (1500-1650).

Closer to us in both geography and time, Ronald Reagan appropriated the imagery of the supposed good times under Coolidge and Eisenhower to legitimate his regime of social destruction. And since that time, every Republican candidate for office has, in turn, presented the recuperation of the supposed good times under Reagan the prime goal of his or her run of "public service".

Meanwhile, the US left (or what passes for it) has resolutely refused to dig into the treasure trove of its rich past in their efforts to mobilize the populace. Indeed, the man who sits in the White House has, to my knowledge, has only spoken openly of having one hero from this country's contemporary past.

Who was it? Ronald Reagan - the patron saint of all those that hurl hate and misinformation against him in today's political environment.

An entire archive of the left's role in generating the great American middle class is dying before our eyes, not because, as is so often repeated, it has no natural constituency, but because its nominal custodians refuse to mount even the most feeble defense of the values contained therein.

In politics, if a body of values and ideas lies untouched for more than two generations, it generally dies. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say, that for most of my generation and all that of my students the idea that insuring dignity, and freedom from unnecessary privation, can and should be the organizing principle of society, has virtually no palpable presence in their lives.

To build anew is noble and necessary. But as studies of trans-generational poverty demonstrate, doing so is infinitely more difficult when privation has been one's only norm.

The same is true in culture and politics. Recent studies in cognitive science increasingly suggest that we can only truly conceptualize the things for which we have an available vocabulary.

I think we all are hoping desperately for some form of social and political renewal. But can we really expect it when, to paraphrase Milton Friedman, the only "ideas lying around" in considerable quantities within our public space belong to the other side?

This past week, I had the pleasure of teaching the Last Supper, Tomas Gutierrez Alea's 1976 masterpiece, to a group of very bright and conscientious undergraduate students.

The film is set on a Cuban sugar plantation in the waning years of the eighteenth century and tells the story of how the owner the place, a Spanish Count who has developed a certain penchant for the liberal ideals then circulating in the court of Spain's "enlightened despot", Carlos III, decides to democratize the traditional celebration of Holy Week at his Caribbean property.

Just as a true appreciation of Stephen Colbert depends on having seen a real conservative blowhard in action, a real understanding the Cuban film depends on having at least a skeletal understanding of the iconic importance of the Last Supper within Christian life, and from there, the entire trajectory of Western Culture.

We can agree or disagree on the wisdom and/or the efficacy of the lessons contained in the event which, we are told, took place in an upper chamber of a building in Jerusalem some two thousand years ago. What we cannot do and be honest with ourselves is to deny its absolutely central importance to the making of our received cultural inheritance.

To take just one of virtually thousands of examples that could be adduced, there can be no real comprehension of what drove Martin Luther King's doctrine of non-violence without an understanding of the importance in his life, and that of millions of other Americans (both black and white), of that Holy Thursday narrative of extreme self-sacrifice.

I have probably taught the Last Supper 5 or 6 times over the last eighteen years. During that time, I have, I think, become fairly aware of some of the challenges it presents to North American students. One is its Cuban provenance. Some students have trouble getting beyond the fact that it is a film imported from what they know to be a "bad" Communist country.

Another is its relatively slow narrative rhythm. Though we don't often talk about it, the insertion into the mainstream of US cinematic practices some time in the nineties of the of frequent, quick and jarring visual cuts developed originally in the advertising and music video industries has fundamentally altered the narrative expectations of young viewers. If the film does not move along in what they consider to be a "normal" temporal cadence, they have a certain tendency to simply tune it out.

I have found, however, that if I address these issues in a straightforward manner at the beginning of our analysis, students can often burrow quite deeply into the film, eventually coming to appreciate its superb construction and challenging messages.

This last time, however, I encountered a challenge that had never before presented itself: a clear majority of the students were largely unfamiliar with the basic narrative of what is said to have gone on at that first Last Supper two millennia ago.

And that got me thinking, among other things, about the issue of cultural transmission in our day.

I would like to make clear that my intention here is not to bash my students. These are sharp young people possessing lots of curiosity and general levels of personal aplomb and directedness that I could not have dreamed of having at their age. They have spent their lives in the midst of a revolution of information availability that has few, if any, parallels in the history of the world. In such unsettled times, is to be expected that many previously "indispensable" facts get shunted aside or simply forgotten.

But my ability empathize with my student's situation in this new information environment does not, I must admit, allay my nervousness about what it portends for those of us that seek to engender the creation a more just and humane world.

Though we--especially those of us that live here in the linearly-minded West of the West--most frequently use vocabulary associated the processes of "birth" and "invention" to describe great cultural and political changes, these metaphors are not terribly apt.

Much more accurate, in my view, would be to speak in terms of alchemy and recombinance. Most great leaps forward in social consciousness have come about not as the result of the generation of wholly new ideas, but rather through the creative redeployment and repurposing of old ones.

When the prosperous merchant class of late medieval Italy wanted to show the world its vital energy, it mined the toolbox of the Greek and Roman classics. The result was what we now call the Renaissance. When, starting a hundred and fifty years ago, the Catalan bourgeoisie wanted to demonstrate its modernity, and with it, its differentness from its counterparts in the rest of Spain, it delved--selectively as had northern Italians done with the Greeks and Romans-- into its own storied medieval past. The result, among many other things, was the stunning modernista architecture that now makes Barcelona one of the world's great tourist destinations.

The same rules apply in politics. When seeking to convince a skeptical populace of the legitimacy of his brutal dictatorship (1939-1975), Francisco Franco borrowed liberally from the iconography of Spain's Golden Age (1500-1650).

Closer to us in both geography and time, Ronald Reagan appropriated the imagery of the supposed good times under Coolidge and Eisenhower to legitimate his regime of social destruction. And since that time, every Republican candidate for office has, in turn, presented the recuperation of the supposed good times under Reagan the prime goal of his or her run of "public service".

Meanwhile, the US left (or what passes for it) has resolutely refused to dig into the treasure trove of its rich past in their efforts to mobilize the populace. Indeed, the man who sits in the White House has, to my knowledge, has only spoken openly of having one hero from this country's contemporary past.

Who was it? Ronald Reagan - the patron saint of all those that hurl hate and misinformation against him in today's political environment.

An entire archive of the left's role in generating the great American middle class is dying before our eyes, not because, as is so often repeated, it has no natural constituency, but because its nominal custodians refuse to mount even the most feeble defense of the values contained therein.

In politics, if a body of values and ideas lies untouched for more than two generations, it generally dies. Indeed, it is no exaggeration to say, that for most of my generation and all that of my students the idea that insuring dignity, and freedom from unnecessary privation, can and should be the organizing principle of society, has virtually no palpable presence in their lives.

To build anew is noble and necessary. But as studies of trans-generational poverty demonstrate, doing so is infinitely more difficult when privation has been one's only norm.

The same is true in culture and politics. Recent studies in cognitive science increasingly suggest that we can only truly conceptualize the things for which we have an available vocabulary.

I think we all are hoping desperately for some form of social and political renewal. But can we really expect it when, to paraphrase Milton Friedman, the only "ideas lying around" in considerable quantities within our public space belong to the other side?