SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Two summers ago, at the U.S. Social Forum, I attended a panel discussion about ways to expand the use of credit unions as alternatives to the "too big to fail" banks whose risky investments had helped tank the economy. Each of the speakers--people involved in credit union leadership or advocacy--expressed confusion and frustration that they hadn't already seen a post-crisis shift away from corporate banks and toward credit unions (which have the advantages of being not-for-profit, owned and governed by their depositors, far more likely than big banks to lend to small businesses, and not responsible for any global economic meltdowns).

It seemed that even as Americans were angry with Big Finance, they didn't make the connection to their personal accounts.

Fast forward to last fall--when Occupy Wall Street was in full swing and activists were mobilizing around Bank Transfer Day, an effort to get customers to leave their Wall Street banks--and it seemed everybody was making the connection. Suddenly I was overhearing conversations on the ferry, on the bus, on the soccer field. People kept saying, "I really should have done this a long time ago, but I'm switching from Bank of America [or Chase, or Wells Fargo]. What bank do you use?" Local credit unions and community banks started staying open for extra hours to accommodate the rush of new customers. One morning in November, at my own credit union, I overheard a man explaining to the teller that he was considering becoming a member--but first he wanted to know if his money would be invested in mortgage-backed securities or credit default swaps.

This change, it turns out, was much more than anecdotal. A new analysis from the firm Javelin Strategy and Research found that, in the last 90 days, Americans changed banking providers at three times the normal rate, with 5.6 million people moving their money to a different bank.

Bank Transfer Day wasn't the first major effort to get people to ditch Wall Street banks, but it was the first to have this level of impact. Arianna Huffington spearheaded a 2010 mobilization, the Move Your Money Project, to move customers to community banks ("Our money has been used to make the system worse--what if we used it to make the system better?" she wrote). While the project gained a fair amount of interest, Javelin reports that the actual bank defections it prompted failed to register on its surveys.

So why was 2011's exodus so much bigger? Eleven percent of those who moved their money--some 610,000 people--reported that they did so directly because of Occupy Wall Street and Bank Transfer Day. The Occupy movement helped bring corporate power to the forefront of national discourse; Bank Transfer Day offered a clear, practical way for people to send a message--a chance to turn the mundane question of bank choice into a stance about their personal economic values.

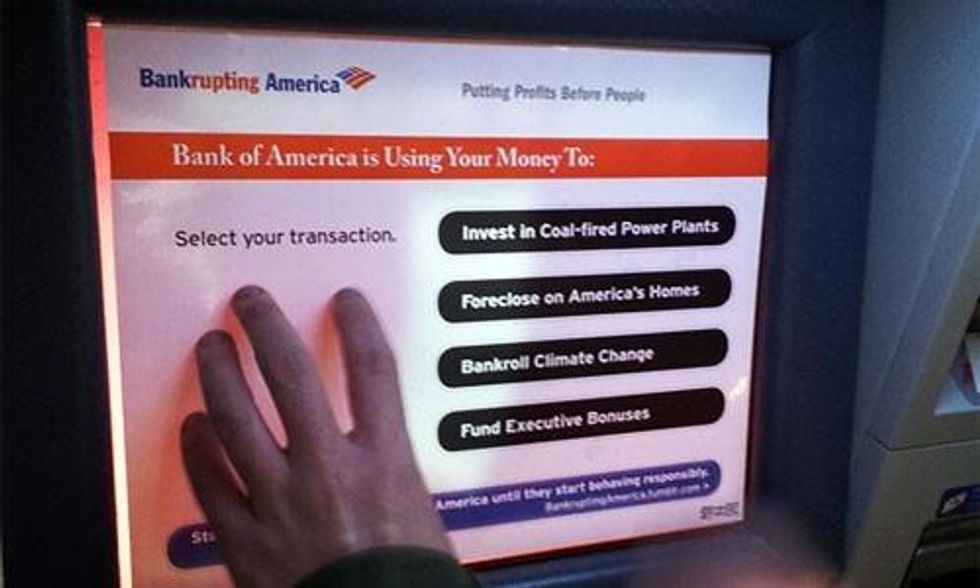

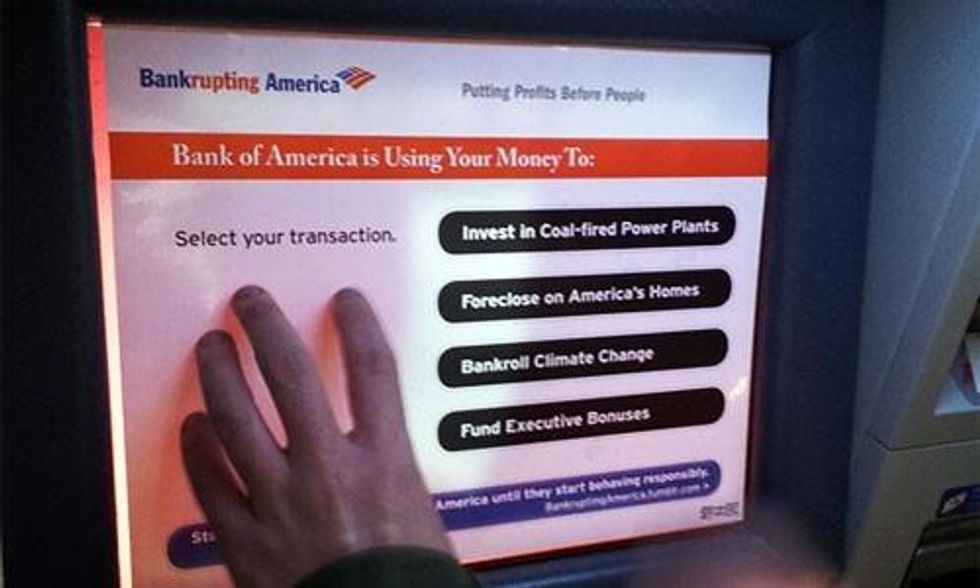

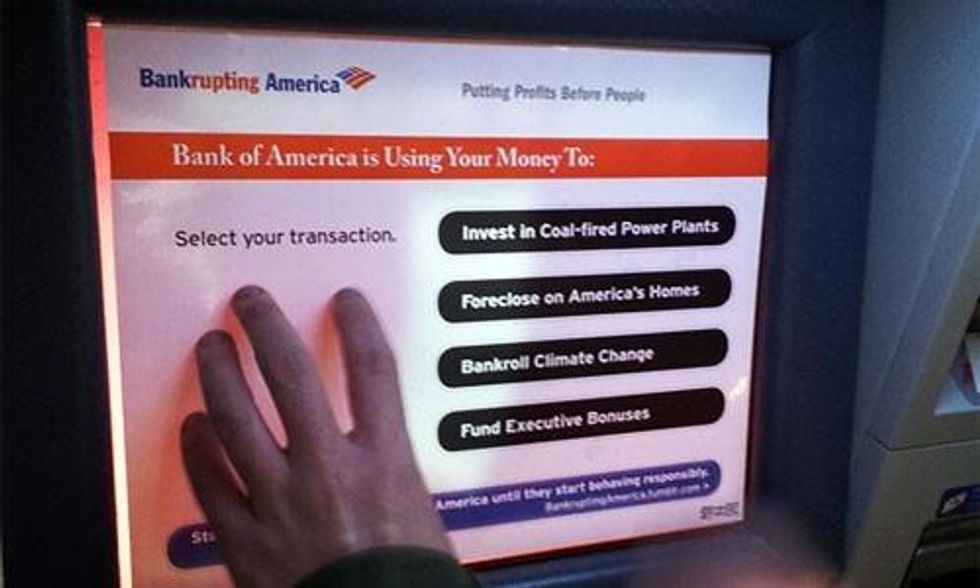

Then, just as the Occupy movement--and the media scrutiny it prompted--got more Americans thinking critically about the role of big banks in their lives, Bank of America announced a new monthly fee on debit card use. BofA became an instant poster child for out-of-control corporate greed, with hundreds of thousands of people signing petitions against the fee or pledging to close their accounts. President Obama condemned it; a Fox Business anchor cut up her card on the air. Eventually, Bank of America pulled the idea, but not before helping to confirm, for millions of Americans, the Occupy movement's charges that Wall Street banks operate by putting profits before public good--as they did with the practices that caused the financial crisis.

"It's just a $5 fee, but it really is symbolic of so much more," Norma Garcia, of the advocacy group Consumers Union, told the Washington Post. In the end, it helped launch Bank Transfer Day to new heights: 26 percent of those who changed banks cited excessive fees at their current institution.

Fees, of course, are just one of many reasons to switch to a credit union (though there's an interesting history--very much related to the deeper problems of corporate banks--that explains why credit unions and community banks tend to have lower fees). Still, the Bank of America backlash was a significant reminder, to the finance industry as well as to consumers, that giant banks aren't the only option--and that there are a variety of advantages to being mindful about what we support with our investments.

Indeed, the bank transfer push doesn't seem to be losing momentum, as large institutional accounts--including cities, universities, and churches--continue to join the bandwagon. San Jose, Calif. moved $1 billion from Bank of America; just this week, Berkeley announced a desire to move its reserves from Wells Fargo to local credit unions; and proposals are under consideration in Portland, Los Angeles, and New York City.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Two summers ago, at the U.S. Social Forum, I attended a panel discussion about ways to expand the use of credit unions as alternatives to the "too big to fail" banks whose risky investments had helped tank the economy. Each of the speakers--people involved in credit union leadership or advocacy--expressed confusion and frustration that they hadn't already seen a post-crisis shift away from corporate banks and toward credit unions (which have the advantages of being not-for-profit, owned and governed by their depositors, far more likely than big banks to lend to small businesses, and not responsible for any global economic meltdowns).

It seemed that even as Americans were angry with Big Finance, they didn't make the connection to their personal accounts.

Fast forward to last fall--when Occupy Wall Street was in full swing and activists were mobilizing around Bank Transfer Day, an effort to get customers to leave their Wall Street banks--and it seemed everybody was making the connection. Suddenly I was overhearing conversations on the ferry, on the bus, on the soccer field. People kept saying, "I really should have done this a long time ago, but I'm switching from Bank of America [or Chase, or Wells Fargo]. What bank do you use?" Local credit unions and community banks started staying open for extra hours to accommodate the rush of new customers. One morning in November, at my own credit union, I overheard a man explaining to the teller that he was considering becoming a member--but first he wanted to know if his money would be invested in mortgage-backed securities or credit default swaps.

This change, it turns out, was much more than anecdotal. A new analysis from the firm Javelin Strategy and Research found that, in the last 90 days, Americans changed banking providers at three times the normal rate, with 5.6 million people moving their money to a different bank.

Bank Transfer Day wasn't the first major effort to get people to ditch Wall Street banks, but it was the first to have this level of impact. Arianna Huffington spearheaded a 2010 mobilization, the Move Your Money Project, to move customers to community banks ("Our money has been used to make the system worse--what if we used it to make the system better?" she wrote). While the project gained a fair amount of interest, Javelin reports that the actual bank defections it prompted failed to register on its surveys.

So why was 2011's exodus so much bigger? Eleven percent of those who moved their money--some 610,000 people--reported that they did so directly because of Occupy Wall Street and Bank Transfer Day. The Occupy movement helped bring corporate power to the forefront of national discourse; Bank Transfer Day offered a clear, practical way for people to send a message--a chance to turn the mundane question of bank choice into a stance about their personal economic values.

Then, just as the Occupy movement--and the media scrutiny it prompted--got more Americans thinking critically about the role of big banks in their lives, Bank of America announced a new monthly fee on debit card use. BofA became an instant poster child for out-of-control corporate greed, with hundreds of thousands of people signing petitions against the fee or pledging to close their accounts. President Obama condemned it; a Fox Business anchor cut up her card on the air. Eventually, Bank of America pulled the idea, but not before helping to confirm, for millions of Americans, the Occupy movement's charges that Wall Street banks operate by putting profits before public good--as they did with the practices that caused the financial crisis.

"It's just a $5 fee, but it really is symbolic of so much more," Norma Garcia, of the advocacy group Consumers Union, told the Washington Post. In the end, it helped launch Bank Transfer Day to new heights: 26 percent of those who changed banks cited excessive fees at their current institution.

Fees, of course, are just one of many reasons to switch to a credit union (though there's an interesting history--very much related to the deeper problems of corporate banks--that explains why credit unions and community banks tend to have lower fees). Still, the Bank of America backlash was a significant reminder, to the finance industry as well as to consumers, that giant banks aren't the only option--and that there are a variety of advantages to being mindful about what we support with our investments.

Indeed, the bank transfer push doesn't seem to be losing momentum, as large institutional accounts--including cities, universities, and churches--continue to join the bandwagon. San Jose, Calif. moved $1 billion from Bank of America; just this week, Berkeley announced a desire to move its reserves from Wells Fargo to local credit unions; and proposals are under consideration in Portland, Los Angeles, and New York City.

Two summers ago, at the U.S. Social Forum, I attended a panel discussion about ways to expand the use of credit unions as alternatives to the "too big to fail" banks whose risky investments had helped tank the economy. Each of the speakers--people involved in credit union leadership or advocacy--expressed confusion and frustration that they hadn't already seen a post-crisis shift away from corporate banks and toward credit unions (which have the advantages of being not-for-profit, owned and governed by their depositors, far more likely than big banks to lend to small businesses, and not responsible for any global economic meltdowns).

It seemed that even as Americans were angry with Big Finance, they didn't make the connection to their personal accounts.

Fast forward to last fall--when Occupy Wall Street was in full swing and activists were mobilizing around Bank Transfer Day, an effort to get customers to leave their Wall Street banks--and it seemed everybody was making the connection. Suddenly I was overhearing conversations on the ferry, on the bus, on the soccer field. People kept saying, "I really should have done this a long time ago, but I'm switching from Bank of America [or Chase, or Wells Fargo]. What bank do you use?" Local credit unions and community banks started staying open for extra hours to accommodate the rush of new customers. One morning in November, at my own credit union, I overheard a man explaining to the teller that he was considering becoming a member--but first he wanted to know if his money would be invested in mortgage-backed securities or credit default swaps.

This change, it turns out, was much more than anecdotal. A new analysis from the firm Javelin Strategy and Research found that, in the last 90 days, Americans changed banking providers at three times the normal rate, with 5.6 million people moving their money to a different bank.

Bank Transfer Day wasn't the first major effort to get people to ditch Wall Street banks, but it was the first to have this level of impact. Arianna Huffington spearheaded a 2010 mobilization, the Move Your Money Project, to move customers to community banks ("Our money has been used to make the system worse--what if we used it to make the system better?" she wrote). While the project gained a fair amount of interest, Javelin reports that the actual bank defections it prompted failed to register on its surveys.

So why was 2011's exodus so much bigger? Eleven percent of those who moved their money--some 610,000 people--reported that they did so directly because of Occupy Wall Street and Bank Transfer Day. The Occupy movement helped bring corporate power to the forefront of national discourse; Bank Transfer Day offered a clear, practical way for people to send a message--a chance to turn the mundane question of bank choice into a stance about their personal economic values.

Then, just as the Occupy movement--and the media scrutiny it prompted--got more Americans thinking critically about the role of big banks in their lives, Bank of America announced a new monthly fee on debit card use. BofA became an instant poster child for out-of-control corporate greed, with hundreds of thousands of people signing petitions against the fee or pledging to close their accounts. President Obama condemned it; a Fox Business anchor cut up her card on the air. Eventually, Bank of America pulled the idea, but not before helping to confirm, for millions of Americans, the Occupy movement's charges that Wall Street banks operate by putting profits before public good--as they did with the practices that caused the financial crisis.

"It's just a $5 fee, but it really is symbolic of so much more," Norma Garcia, of the advocacy group Consumers Union, told the Washington Post. In the end, it helped launch Bank Transfer Day to new heights: 26 percent of those who changed banks cited excessive fees at their current institution.

Fees, of course, are just one of many reasons to switch to a credit union (though there's an interesting history--very much related to the deeper problems of corporate banks--that explains why credit unions and community banks tend to have lower fees). Still, the Bank of America backlash was a significant reminder, to the finance industry as well as to consumers, that giant banks aren't the only option--and that there are a variety of advantages to being mindful about what we support with our investments.

Indeed, the bank transfer push doesn't seem to be losing momentum, as large institutional accounts--including cities, universities, and churches--continue to join the bandwagon. San Jose, Calif. moved $1 billion from Bank of America; just this week, Berkeley announced a desire to move its reserves from Wells Fargo to local credit unions; and proposals are under consideration in Portland, Los Angeles, and New York City.