Why the Left Should Not Join Trump or BRICS' Attack on Globalism

US hegemony and a neoliberal faith in unfettered markets are noxious to be sure, but don’t be fooled by autocrats championing sovereignty

President Donald Trump hates Antifa. He hates late-night TV hosts, Democratic-controlled cities, and anyone who has ever challenged him in court. As of October, he officially hates the Nobel committee for not giving him a peace prize, despite his efforts to strong-arm its members into voting for him.

The president has gone after everyone he thinks has ever done him wrong. But there is a Venn diagram to his vendettas, an overlap in his circle of obsessions.

Map out his attacks, subtracting the purely personal and the primarily partisan, and you’ll see that they converge on a profound disgust for the liberal international order. That Trump has personally profited from that very global order—his portfolio of international real estate, his business’s reliance on global supply chains, the unacknowledged benefits he’s accrued from the international rule of law—makes no difference.

“Globalists” like Barack Obama, George Soros, and Emmanuel Macron have made fun of him, not fully accepting him into their ranks and refusing to acknowledge his brilliance with medals and awards. In the president’s skewed accounting ledger, the gatekeepers at the global country club who don’t want him as a member must be made to pay.

The dalliance between left and right is taking place at the margins where a mutual disgust for liberalism fuels the romance.

Trump has attacked the liberal international order in seemingly every conceivable way. He’s initiated a global trade war. He’s dismantled US humanitarian assistance to impoverished lands and put pressure on allies to spend more money on war preparations, not welfare programs or foreign aid. He’s destroyed relationships with liberal allies like Canada and the non-Hungarian members of the European Union. He’s levied sanctions against the International Criminal Court (ICC) in an effort to shut it down. He’s gleefully ignored international law by embracing ICC scofflaws like Vladimir Putin and Benjamin Netanyahu. And he’s committed his own crimes, like the extrajudicial murder of the crews of nine boats near the Venezuelan coast and five in the Pacific Ocean.

The United States had long been a pillar of the liberal international order. So, when Trump takes a sledgehammer to its base, he causes potentially irreparable damage to the reputation, power, and global position of the United States. Many Americans, particularly those in the political center, are aghast at the self-inflicted wounds this country is now suffering.

In other quarters, however, there’s celebration.

America’s right wing has long hated everything that shimmers in the distance beyond the territorial waters of this country. The United Nations gives it indigestion. Ditto the European Union, the Third World, and anything connected to universal human rights. The most reactionary elements of the Republican Party have blocked Washington’s ratification of international treaties, undermined global efforts to address threats like climate change, and claimed to spot communist (or Islamist or terrorist) conspiracies behind every international institution and many nationalist movements. Such right-wingers have pushed to eliminate all forms of soft power in favor of beefed-up hard power. The ascendancy of Trump has provided them with an opportunity to force conventional conservatives from their party, while consolidating an America First position.

Elements of the left, too, have rejoiced in Trump’s globalism bashing. The most predictable support has come from unions that believe the president’s tariffs will protect American jobs. But some leftists have also been hesitant to support the work of the now largely shuttered US Agency for International Development (USAID)—even its distribution of AIDS medicines and climate funds—because of its legacy as a “destructive arm of American imperialism.” Some have even joined hands with Trump to deride NATO and echo Kremlin talking points on Ukraine. In the lead-up to the 2024 election, the odd progressive even mistook Trump for an anti-imperialist.

Once upon a time, adventurous theorists imagined that communism and capitalism might both end up adopting some version of democratic socialism, as a reformed Soviet Union and an increasingly welfare-state-oriented United States seemed to be converging on the Swedish model. In the early 1980s, however, the leaders of the two superpowers of that time, Leonid Brezhnev and Ronald Reagan, teamed up to drive a knife through that particular fantasy.

Today, a different convergence is in process and the two poles are not meeting in the middle. Rather, the dalliance between left and right is taking place at the margins where a mutual disgust for liberalism fuels the romance. This courtship has developed its own love language. Both sides love to hate “globalism”—and, of course, the globalists who globalized it.

Trump stands astride that consensus like an angry god, urging his followers to tear down the temples and wreak vengeance on those who worship foreign deities. Meanwhile, some Marxists mutter approvingly of “sharpening the contradictions”—the notion that Trump will make things so bad that the masses will rise up in reaction. Meanwhile, MAGA followers love the spectacle of destruction that clears the way for white people, rich people, or just plain mean people to take over.

The left and the right still maintain very different visions of the future: maximum justice versus maximum injustice. But their odd convergence against the international liberal elite helps to explain MAGA’s success in certain Democratic strongholds. “Throw the globalist bums out” is a tagline that can appeal to both ends of the political spectrum.

As the poet William Butler Yeats observed after the end of the First World War, the center is not holding, while the best lack all conviction. During this second coming of Donald Trump, however, you better believe that it won’t be mere anarchy that is loosed upon the world.

Globalism, No. Multipolarism, Yes?

Multipolarism has lately become all the rage. The notion that the world could have multiple centers of power in contrast to the bipolarism of the Cold War or the aspirational unipolarism of the United States after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 is anything but new. Still, with the “rise of the rest” and the ascent of China in particular, the world has begun to look ever less US-centric.

For many, however, multipolarism isn’t just a description, it’s a prescription, too.

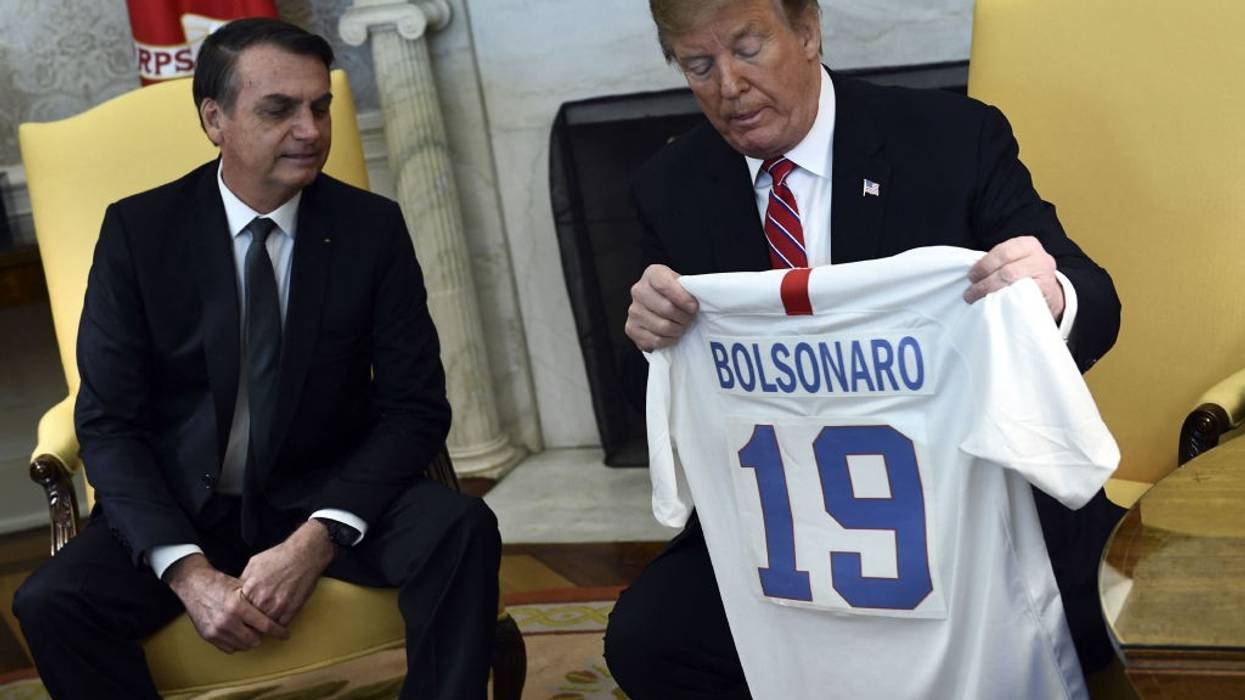

On the right, philosophers like Alexander Dugin in Russia and Olavo de Carvalho in Brazil have used the concept as part of their ultra-nationalist projects. For Dugin, Russia must reassert its superpower status as part of a new Eurasian force to block the Anglo-Saxons and their NATO henchmen. For Carvalho, who died in 2022, multipolarism would enable Brazil to move closer to the Christian West, while shrugging off its subservience to global elites.

Some on the left, too, have identified multipolarism as a sign of a more equitable geopolitics—and a potential cudgel against American imperialism. As the Tricontinental editorialized in 2022:

The longed-for Western, globalised capitalist world has not lived up to the expectations of even its most enthusiastic advocates. Today we are witnessing a shift towards a multipolar world, despite the aspirations of neoliberal globalists, neoconservatives, and those who favour the US model of development (‘Americanists’).

Enter the BRICS

If multipolarism seems like a magic elixir to many, today’s vessel of choice for it is the BRICS. Over the years, many multipolar efforts have fallen by the wayside, including the Non-Aligned Movement, the New International Economic Order, the Group of 77, and the World Social Forum. But the institutions created by Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) beginning in 2010 were seen by multipolarists as the inheritors of those earlier movements for non-alignment and so a potential counterforce to US and Western power. According to such a scenario, the BRICS would sooner or later replace the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), dethrone the dollar, and remake the entire global economy.

For some on the left, support for the transformative nature of BRICS recalls arguments used to defend Russia from charges of imperial designs on Ukraine. By supposedly holding the line against the enlargement of the European Union and the expansion of NATO, Russia was seen as standing up to the West. The globalists responded with the same kind of sanctions they’d applied to Cuba, North Korea, and Venezuela. Unlike the leaders of those three countries, however, Vladimir Putin has never pretended to be a man of the left. Instead, as a right-wing authoritarian leader, he’s killed opponents; thrown dissidents in jail; eliminated an independent media in Russia; and imposed a religious, anti-LGBT, misogynistic agenda on its society. He’s also revived Russian imperialism with his invasion of Ukraine, his political meddling in Moldova, and his cyber-interference in the Baltic countries.

The cognitive dissonance required for a progressive to defend Putin carries over to any enthusiasm for BRICS as a whole. After all, a majority of the countries in that 11-member group—Russia, China, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—are presided over by autocrats. Only Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia, and India are democracies, and the last two come with asterisks, given the autocratic tendencies of their current leaders. Moreover, the anti-imperial credentials of the bloc are suspect, considering Russia’s interference in its “near abroad,” China’s position toward Taiwan, India’s efforts in Kashmir, and the Saudi war in Yemen. At best, many of the BRICS members are sub-imperial, as political economist Patrick Bond has long argued.

As a bloc of mostly authoritarian, eco-unfriendly, and socio-economically conservative countries masquerading as a geopolitical counterbalance, the BRICS represent the multipolarism of fools.

The BRICS also generally have a distinctly regressive position on climate change, which is hardly surprising given that the majority of them are significant fossil-fuel exporters. Brazil has been pushing its fellow members to focus on climate change as a threat to the planet, and a number of BRICS statements do acknowledge the importance of reducing carbon emissions. But China, despite its massive investments in the green energy revolution, remains stunningly dependent on the worst of the fossil fuels, coal, as do India and Indonesia, while carbon neutrality remains a distant goal for Russia (2070). In the latest BRICS statement, the members “acknowledge fossil fuels will still play an important role in the world’s energy mix, particularly for emerging markets and developing economies.”

But the conservative nature of the BRICS is perhaps most strikingly on display in its embrace of the global capitalist economy. Its July 2025 statement enthusiastically endorsed both the IMF and the World Bank, and put the World Trade Organization at the center of the global trading system. The principal BRICS institution, the New Development Bank, has been heralded as a building block for a new economic order, but its focus on financing the same old dirty extraction projects makes it a mirror image of the World Bank.

The BRICS mode of multipolarism has but a single progressive attribute: its potential as a counterbalance to US imperial power. Unfortunately, even a tepid challenge to Washington’s authority has produced a predictable backlash from Donald Trump, a leader committed not just to US unipolarism but to his own unileaderism. To the imaginary threat that the BRICS would actually create a currency to challenge the dollar, Trump has repeatedly warned that “any country aligning themselves with the Anti-American policies of BRICS, will be charged an ADDITIONAL 10% tariff.”

Toward a True Internationalism

In its BRICS form, multipolarism boils down to, at best, an effort to get a better seat at the table with the big boys. At worst, it’s a repudiation of the progressive parts of internationalism, especially global efforts to rein in abuses of power through higher standards on human rights, the environment, and labor.

To support the regressive multipolarism of the BRICS countries, elements of the right and left trumpet the importance of sovereignty and the notion that a country’s leadership has uncontested control over the territory within its borders. Sovereignty is indeed under attack on all sides. At a territorial level, the most obvious violation is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. At the economic level, neoliberal globalists want to challenge sovereign economic power through corporate attacks on state regulations and the IMF’s imposition of budget austerity in its loan agreements. Internationalists, by contrast, focus on democratically agreed-upon norms around human rights, while challenging the state’s prerogative to deploy child soldiers, employ child workers, or kill off large parts of the population.

Progressive internationalists should, however, be wary of conservative notions of sovereignty. Sure, we loathe the IMF’s overreach and the way oil companies take countries to court to dismantle their environmental regulations. But we also don’t believe that kings, tyrants, or even democratically elected autocrats should have the freedom to invade other countries or engage in extrajudicial killings. Sovereignty is not a trump card (or a Trump card). Popular sovereignty, where power is in the hands of the people, is certainly indispensable in securing more democratic societies. But as Trump and his friends like Nayib Bukele of El Salvador and Viktor Orbán of Hungary have demonstrated, autocrats often use the language of popular sovereignty to gain office before concentrating power in their own sovereign hands.

It’s a dispiriting irony that just when the world needs more internationalism to address climate change, economic inequality, and pandemics, among other devastating realities, it’s also experiencing an upsurge in nationalism propagated by the sovereignistas. Promoting internationalism these days feels a lot like embracing a Palestinian state when the material basis for such a state is disappearing beneath a rising tide of Israeli settlements and bombs. In both cases, there is a will but not, it seems, a way.

Progressives should not join hands with the right in a misguided attack on “globalists.” US hegemony and a neoliberal faith in unfettered markets are noxious to be sure, but don’t be fooled by autocrats championing sovereignty. As a bloc of mostly authoritarian, eco-unfriendly, and socio-economically conservative countries masquerading as a geopolitical counterbalance, the BRICS represent the multipolarism of fools. The ends do not justify the BRICS.

Call me a globalist, but someone has to stick up for this planet when so many extremists, whatever they may call themselves, have their knives out to carve Earth up into their own fiefdoms of bigotry.

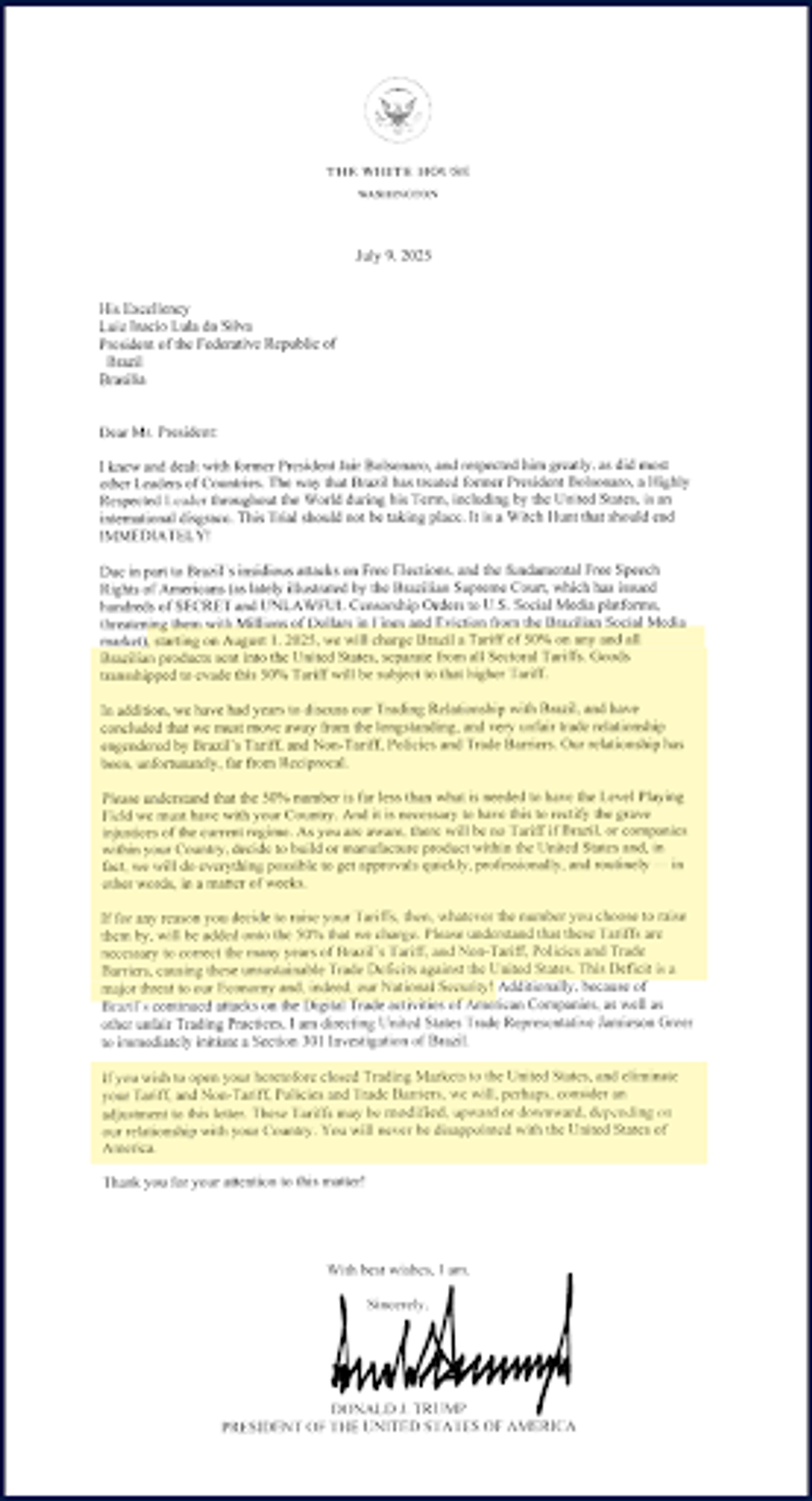

Trump’s letter to Brazil announcing the new tariffs. Highlighted text was present in the form of letters sent to more than a dozen other countries.

Trump’s letter to Brazil announcing the new tariffs. Highlighted text was present in the form of letters sent to more than a dozen other countries.