Every disaster is unique, but some general observations apply. When a disaster happens, our normal sense of time is interrupted and our priorities get scrambled. Suddenly, nothing matters but the immediate necessities of escaping harm and helping others to safety. People’s attitudes tend to be sober, purposeful, and helpful; hysteria is rare. Everyone’s implicit goal is to get back to something approximating normal. Importantly, disasters also tend to evoke a similar community-minded response in people: At least in the short run, they work together creatively to meet one another’s basic needs.

Environmental disasters are sometimes the easiest for victims to mentally comprehend, though not always to recover from. After floods, fires, earthquakes, and chemical spills, immediate response efforts are led by the affected region and surrounding communities, while longer-term recovery typically depends on national governmental assistance. Neighbors pull together to make sure all are safe (see this account of my experience during the 2017 wildfires in my hometown of Santa Rosa, California).

Severe political conflicts can therefore be more psychologically devastating than environmental or economic disasters. But, as we will see, they can also evoke extraordinary levels of community solidarity and mutual aid.

Economic disasters can linger for years and can scar a generation, as occurred during and in the wake of the Great Depression of the 1930s, and in the currency collapses that have plagued several nations over the last century. The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 and the Covid-19 pandemic, though relatively short in duration, saw large-scale failure of businesses and disappearance of jobs. Again, it’s typically up to local communities to help meet people’s immediate needs until the national government can intervene to provide aid and stability.

Political disasters (including civil conflicts) are often different in significant ways. In some instances, they turn neighbor against neighbor, or communities against their national government. Government may hurt rather than help; indeed, government may be out to get you. Severe political conflicts can therefore be more psychologically devastating than environmental or economic disasters. But, as we will see, they can also evoke extraordinary levels of community solidarity and mutual aid.

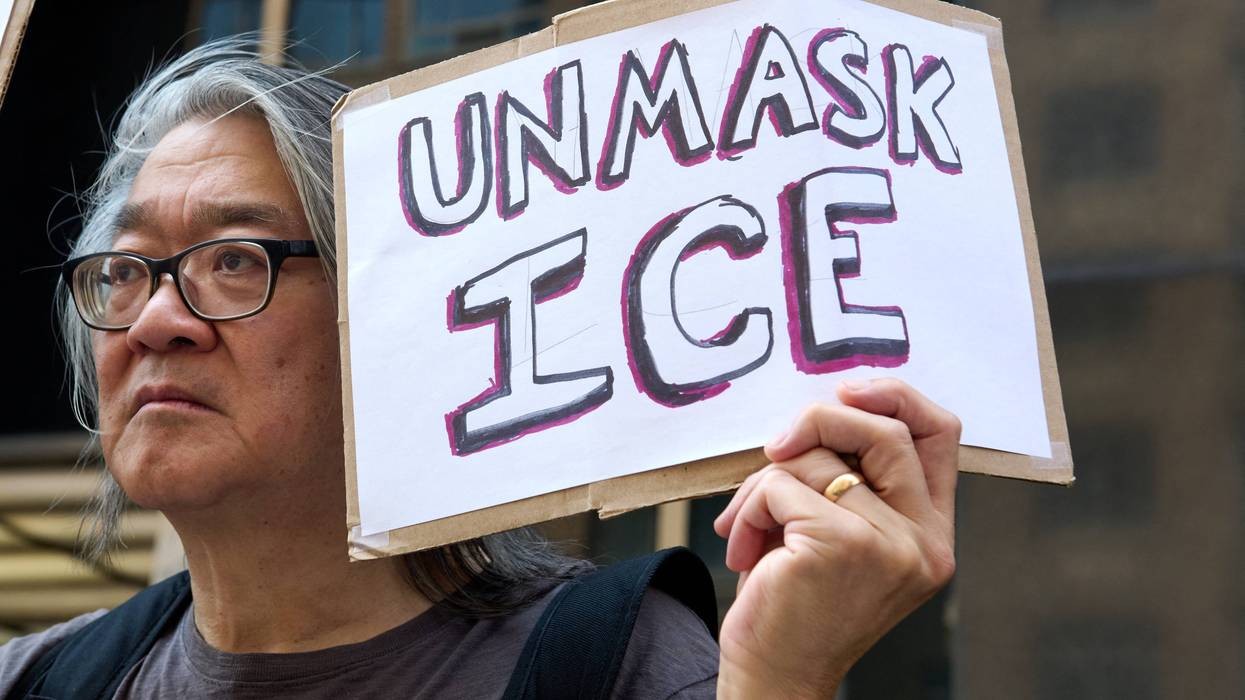

The Great Unraveling of environmental and social stability will feature all three kinds of disasters. Currently, global breakdown is being accelerated primarily by an ongoing and worsening political calamity in the United States. In this article, we’ll go to the frontlines of conflict in Minneapolis to see how people are responding to a violent—even deadly—government-imposed crisis. As the Trump regime promises to end its surge of federal agents in that city, perhaps it’s a good time to reflect: What have we learned that might be helpful in future crises?

A City Under Siege

Recent events in Minneapolis and surrounding communities are being widely reported and analyzed. They’ve even been iconified in a Bruce Springsteen song. Our purpose here is to see what we can glean that’s relevant for the larger project of surviving the Great Unraveling.

First, some background facts. Following deployments of troops and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents to Los Angeles, Chicago, and Portland, on January 6, 2026 president Donald Trump sent nearly 3,000 ICE and Border Patrol agents to Minneapolis—a medium-sized city of fewer than half a million residents. There is widespread speculation that the ICE surge was politically motivated, as Minneapolis is a bright blue* town in a blue state whose governor, Tim Walz, was the Democratic vice-presidential candidate in 2024. The massive deployment of federal agents dwarfed the city’s police force of 600 officers.

Trump and his officials have stated that the purpose of the ICE surge is to remove “the worst of the worst”—undocumented immigrants who are thieves, rapists, and murderers. However, officials have imposed unrealistic arrest quotas on agents, requiring them to round up more undocumented people than can be vetted for criminality—as well as US citizens and legal immigrants with green cards or refugee status. The Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a nonprofit research organization, has found that roughly three-quarters of individuals currently detained by ICE do not have a criminal record, and that many who do were convicted of only minor offenses, like traffic violations.

Federal agents have focused their attention on places where undocumented people are likely to be found: restaurants, Home Depot stores, schools, and churches. Often, agents simply grab anyone who looks brown-skinned. They sometimes break into homes without warrants and effectively kidnap the residents, who are then sent to makeshift detention centers; family members may have no idea where their loved ones are for many days.

As a result, many immigrants and non-immigrants alike feel as though they are living under occupation by a hostile army. People are terrified, businesses are closed, workers are staying home, rent payments are falling behind, and children are not going to school.

Resistance Breeds Solidarity

The response of the people of Minneapolis and its surrounding suburbs has been peaceful but organized and insistent. Neighbors are protecting neighbors.

Minnesota has a longstanding tradition of mutual aid and of neighborhood organizing, which intensified after the killing of George Floyd by a police officer in 2020. Residents are making a disciplined effort to avoid violence, even when protesters are being attacked. They’ve created a leaderless cell-based pattern of organization, communicating through Signal (an encrypted social media app). Participants use pseudonyms, and every effort is made to maintain anonymity.

Actions undertaken in response to the specific needs of the community fall under four broad headings: documenting the actions of ICE agents; protesting their presence; protecting vulnerable people; and helping meet those people’s daily needs for food, shelter, schooling, and doctor visits. Often these actions require courage and creativity, as when massed members of the group Singing Resistance walk frozen streets, raising the spirits of fellow community members with songs of solidarity, grief, and rage.

I recently reached out to a friend who lives near Minneapolis to ask about their experience in resistance networks there. The story of what is happening there is best told by someone who is in the thick of it themselves, so I am giving over remainder of this article their words. This is an edited transcript of the comments from my friend, who wishes to remain anonymous:

“My first encounter with ICE was in mid-December. It was a very cold day. I saw construction workers trapped on the roof of a house they were building, and ICE had surrounded it. Very quickly, observers started gathering and blowing whistles. The workers on the roof weren’t prepared to be up there for a long time, so observers were trying to throw them blankets and handwarmers. In the end, one of the workers had to be taken to the hospital for possible frostbite.

"If anything positive is going to come from all this, it’s the fact that people are going to be more connected and more willing to help their neighbors."

“Later, I got involved in response efforts. We have ICE agents staying in hotels where I live, and there are some nicer restaurants that they like to frequent. There were reports of ICE outside one local restaurant. We talked with employees, who said there’s a table of ICE agents eating. Then we were able to identify a car of ICE agents outside, and people started surrounding the car and honking. This was before any of the observers had been killed [i.e., Renee Good and Alex Pretti, both gunned down by ICE and Border Patrol agents], so I think we were a little bolder at that point. One man even got out of his car and walked right up to the ICE vehicle and yelled at them. Then the local police came, but the cops usually say they can’t intervene."

“On another occasion, there was a report of ICE agents outside a [Mexican] restaurant. I was the second observer on the scene; there was already a lady there with her megaphone, making noise. We had identified three ICE vehicles in the parking lot. So, we started driving around trying to get their plates so we could have them in our records and verify they were in fact federal agents. The goal was to make enough noise to hopefully get the agents to leave. We’re honking and flashing lights at them, and they’re flashing lights at us. They were obviously irritated. Within 20 minutes, between 15 and 20 additional cars showed up to observe and show support for the cornered workers. One by one, they slowly left, and community members helped the workers who were trapped inside to get home safely in cars that weren’t identifiable to them."

“We’ve got a couple of contacts who live in big apartment buildings and who are vulnerable, and they’ve been go-betweens for fundraising. We’ve been able to fundraise to help people pay rent. It’s a domino effect: People are worried about going to work. They stop going to work, and restaurants temporarily close because a lot of their workers are vulnerable. As a result, they can’t earn money, and they’re at risk of losing their job."

“We get specific calls like, hey, we have this family that needs this or that, and people can raise their hands either to fund that, or to drop it off to the liaison who then distributes it, all to keep people’s information private."

“The ICE agents are adapting all the time. They’re changing up their cars, and they’re switching plates. There have been occasions where they are driving around without any plates at all. They were all wearing masks, and now a lot of them are wearing plain clothes to try and blend in more. But as they adapt, we do too."

“I think the community building going on has been impressive because, unlike what the media says, none of us have been paid a cent for this and never expect to be. At a protest the other night, one guy said, ‘There’s no amount that anybody could pay us to not show up for our neighbors.’ I don’t know why people can’t comprehend that people would be doing this just because they care about the well-being of others."

“It’s been an evolution. As people get more involved, they see the different pieces of the puzzle, and then they can contribute. The biggest thing for the people who’ve been leading it longer is that they’re getting burnt out. Many involved already have full-time jobs, and they’re also putting in full-time hours for this effort. So, the longer-term observers are keen to get more people in leadership roles so that the work can be distributed. And the ability to do that has come from just building trust with people you initially may only know anonymously through the phone. That trust comes from showing up repeatedly, putting in the time and effort, and vouching for each other."

“This is a community effort. I don’t think anyone is trying to be recognized for what they’re doing. Everyone involved knows that this is the right thing to be doing. There are a lot of people out there, especially in our government, who try to spin what’s going on here as being terroristic in intent, or that we’re just trying to interfere with government operations or hurt people. But that is so antithetical to what anyone here is actually trying to do."

“There’s risk involved, and the distributed leadership model helps diminish that because then individuals can’t be targeted as easily. But I know some of my local elected representatives have been involved, and they’ve been subject to threats, because they’re public and they’re not hiding their identity."

“Even when the imminent threat of people constantly being taken dies down, there’s going to be more need for community organizing and mutual aid. And so, hopefully, this is cementing a framework that we can continue to expand upon as needs in the community grow through whatever challenge may arise. I think if anything positive is going to come from all this, it’s the fact that people are going to be more connected and more willing to help their neighbors."

“Having these federal agents here and knowing my community is under extreme surveillance is unfamiliar and infuriating to me, but I know it is something like what many marginalized groups have contended with for decades or centuries."

“It is increasingly difficult to leave the house and drive somewhere without viewing every car with suspicion. We wave and smile as I pass through vulnerable neighborhoods, to show we are here to help and not harm. There is a sense that we are always ‘this close’ to an agent feeling justified to smash in our windows or detain us for simply practicing the rights the US Constitution entitles us to. We fear what may come next, what the retribution may be. It is frustrating knowing that if we call the cops with concerns regarding the illegal or unethical behaviors of these agents, we will be met with no response."

“But there is a power in this resistance, a feeling of deep connection and kinship to those around you, even if you just met or only know their online alias. You know you are on the same side of this battle for basic human rights. There’s a feeling that so many people have your back, even if they have never met you. Seeing extreme bravery from regular people encourages your own commitment."

“The biggest feeling of all, though, is the feeling that none of us are doing enough. Despite our efforts, people are still being taken from their families every day to potentially disappear in the system."

“The other frustrating thing, to me, is that this shouldn’t have to be our priority. It wouldn’t be if our United States government were set up in a way that wasn’t so focused on exploiting and ‘othering’ people for money and greed. We could be putting all this energy toward trying to build a more sustainable world rather than just protecting people from being abducted. But this is the imminent threat right now.”